TMR columnist Amal Ghandour reflects on the past year, one rich in disappointment, continuing tragedy, and political smoke and mirrors.

As the end of the year approaches, what do our eyes behold?

In Gaza, for example, my eyes behold a ceasefire unfolding to reveal a different kind of horror, perhaps intended: a much quieter misery. Much quieter to the outside world, that is. Far away witnesses assume there’s not much left of this genocidal scandal to be told. A sigh of relief on the Israeli side; dread and despair on the Palestinian.

I turn my gaze to the West Bank, laboring ever harder under the Israeli apartheid regime. Outside the cities, I behold frantic Israeli ethnic cleansing and pogroms, as if racing against the clock. They barely register in the news. There’s a lesson in that: Israel’s carte blanche stands between the river and the sea. On that much, we all agree.

Still, the much-clichéd horizon over Israel-Palestine remains befogged, difficult to decipher. For Palestinians, the near view is turbid, forbidding; the far one perceptibly sharper, finer. For Israelis, it’s the other way around. It looks like a paradox but it isn’t. Remember that movie starring Barbara Streisand and Yves Montand, On A Clear Day You Can See Forever? In Israel-Palestine, even on the clearest day, the panorama refuses to settle. Ghosts of the past mingle with vectors of the future; old crimes presage misdeeds yet to come. And you know — you just know — this movie is far from over. That’s why the Israeli sigh of relief has always been so premature and deceiving, and the Palestinian sense of dread so tempered by hope and defiance.

They called me the party pooper when I warned that cesspools, too, can glitter — but only for so long.

The pain of it all sharpens as yet another festive season draws near, capping yet another year of lived nightmares and squandered dreams. Then on a random afternoon, a video comes your way on Instagram, showing children somewhere in Gaza laughing as they sway on makeshift swings hung on wreckage. The evening grows slightly less anxious.

My Damascene friends tell me it’s about time I visit; Lebanese who have been concur. It’s a sight, some of them say; it’s such fun, others claim. My Aleppine friends, though, are less sanguine. So are a few journalist chums. The sentiments are anecdotal, of course, but they tend to dovetail. Syria’s prospects appear much improved, if only by the low bar set by Bashar Assad. Bashar’s legacy, after all, is his miserably low threshold. I listen and read and can’t help but recall the euphoria that accompanied Rafiq Hariri’s rise to the premiership soon after the 1975-1990 Lebanese civil war. They called me the party pooper when I warned that cesspools, too, can glitter — but only for so long.

These are my trepidations when the human condition, emerging from extreme duress, justifiably yearns for relief and switches off the mind’s censors. Such is the lay of the land, needless to say, in Lebanon. The festivities here are always early. In Beirut, they come with truly unendurable traffic jams and nervous breakdowns during the day and, depending on the heart’s desire, cheer or pizzazz in the evening. Incessant questions about impending troubles are shoved to the margins of emotions, and uncertainties, on cue, subside until January 3. I need not mention that this privilege is a club to which membership is very limited.

These are just the time-honored traditions of Christmastide and farewell parties to the year we survived. Every new one brings its own rhythms, as always; habits that soon enough become part of the cadence of day-to-day existence. In the south of Lebanon you look upward now, watching for drones, when you’re out in the fields and the streets. That’s how you pray over a loved one’s grave, as well. Or even when you’re sweeping the floor or having your morning coffee on your porch. Sometimes emm Kamel’s voice you hear up there means to prod you in your chores so that it can get on with its own; sometimes it greets you by name just to let you know that it has done its homework on you. When it is silent, it may mean that it’s just about to turn you into a corpse.

In Beirut, we have taken to flipping a discreet finger at emm Kamel, our new Israeli companion droning away in our cityscape. Emm Kamel is an old nickname for an old intruder. Unbeknownst to many Lebanese, Israeli drones were hovering over southern terrains as early as 1982. Apparently, the drone model –– Tadiran Mastiff, commonly referred to as MK –– was the inspiration for the cute sobriquet: emm Kamel, mother of Kamel. Lebanese gallows humor, as you can tell. Back then, emm Kamel was just a busybody; it had infinite curiosity but limited reach. Today, quite the lethal eavesdropper and toy soldier, it not only echoes but footnotes Orwell’s 1984.

They’re ending 2025 in conversation, the Israeli and Lebanese states, to the echoes and beats of these drones, of Israeli thunderbolts, of our own shouting matches. A crescendo punctuated by the harangues of those holding the purse to the money meant to rescue our country –– a country which, rumor has it, sits on some $18B in cash in a $28B economy. The public rows betray very little of what is actually conceded behind closed doors by all parties. They also betray nothing of the people’s quandaries and insecurities as they await the future, the holidays notwithstanding.

And the future that looms, at least in part, is not entirely a mystery. Whatever the talks’ outcome, for the frontline villagers overlooking this side of Israel, the odds of return are bleak. A colleague aptly calls the dislocation of the estimated 100,000 inhabitants a form of internal transfer. If it turns permanent, the social and political consequences are not hard to imagine and will soon turn tangible. The starkest among them is a deep south that is tantamount to a dead zone. Dead to Lebanon.

But it’s never a good day for a would-be reformist government, confronted with these existential challenges, when those atop the helm decide the moment is better suited for a crude sectarian gambit. We have today one camp which, with such reckless relish, behaves as if Hezbollah has lost everything in this latest war, and another which, with such curious dimness, pretends that Hezbollah has lost nothing. Schadenfreude and bombast, in equal measure.

Par for the course, in Lebanon. Regime recalibrations define our troubled modern history. They have been typically violent. Such is the fraught nature of the sectarian contest between those who have too much power and those who feel diminished by it. History, of course, is not necessarily prologue, and not every era replicates the one before it. But our ruling elites are notorious for ignoring its lessons. When opportunity invites them to innovate, their worst impulses rise to the occasion.

Let’s therefore hope that sobriety wins and 2026 denies all of them this opportunity.

On Another Note

I’ll keep it simple this week.

I am a very slow reader. The day is dedicated to my research, the evening, right before bed, to fiction. My nonfiction choices are purposeful; the novels are usually the recommendations of the voracious reader of the family, my sister Raghida. But I do grow very attached to my own favorites.

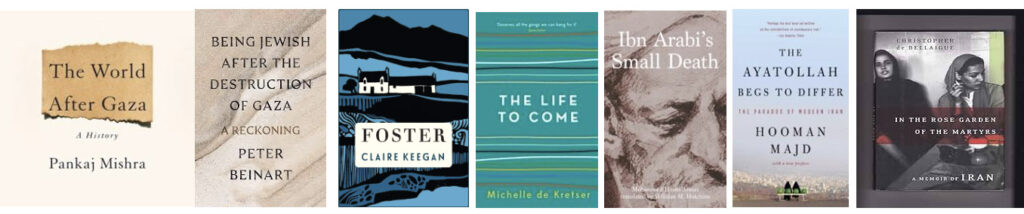

Readers have recently asked me what I’ve been reading. I won’t list all the books, but I will share five that I found profoundly meaningful: Pankaj Mishra’s The World After Gaza, Peter Beinart’s Being Jewish After the Destruction of Gaza, Claire Keegan’s Foster; Michelle de Kretser’s The Life to Come, and Mohammad Hassan Alwan’s Ibn Arabi’s Small Death.

A few readers have also asked me to recommend books that illuminate the human factor in Iran. A hard task, given how rich the offerings are. But I walked away much better informed when I read two particularly insightful books: Hooman Majd’s The Ayatollah Begs to Differ, and Christopher de Bellaigue’s In the Rose Garden of the Martyrs.

Until we meet again, on January 3, 2026!

Amal Ghandour’s biweekly column, “This Arab Life,” appears in The Markaz Review every second Friday, as well as in her Substack, and is syndicated in Arabic in Al Quds Al Arabi.

Opinions published in The Markaz Review reflect the perspective of their authors and do not necessarily represent TMR.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)