Censorship comes in many forms, from veiled threats to tapped phones and bugged apartments, to authorities limiting press access, such as when Israel barred foreign journalists from covering the Gaza onslaught. It could be a straightforward refusal to publish a piece, and sometimes it comes as a thinly veiled intimidation letter from an organization whose job it is to uphold and protect the writer’s work.

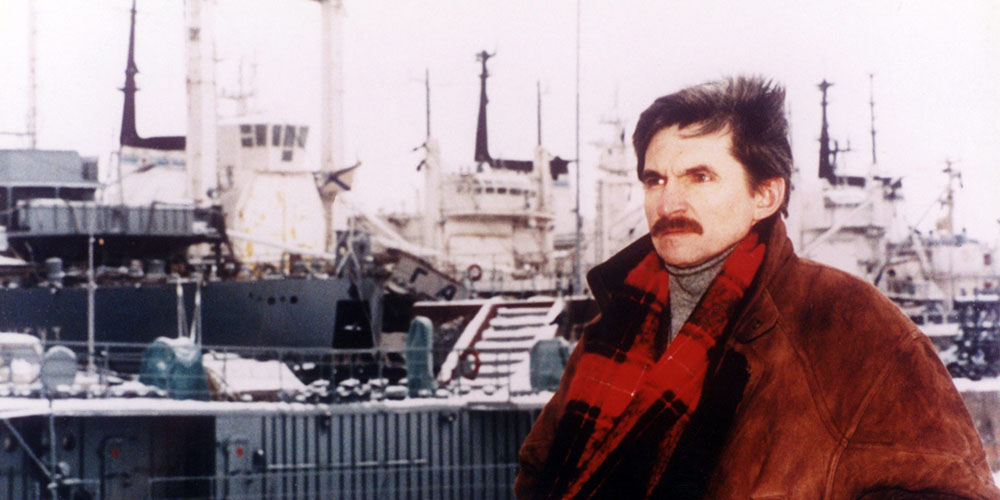

Anna Badkhen

On December 29, 1999, a court in St. Petersburg, Russia acquitted of all charges the whistleblower Alexander Nikitin, whom the Russian security police had accused of espionage and treason on grounds so secret neither Nikitin nor his lawyers were allowed to read them. After the hearing, I approached the prosecutor for comment. It was a standard of journalistic conduct that I, a 24-year-old reporter, was determined to uphold. The prosecutor had a comment just for me.

“Don’t you have a toddler at home, Anna?” he said. “You should go check on your child.”

Censorship comes in many forms, and nearly three decades of being a full-time writer — in Russia, in the United States, in warzones —have taught me to recognize it on the spot. Sometimes it is a friendly reminder that your child is being watched or your apartment is bugged and your phone is tracked. Sometimes it is the authorities’ move to limit access, as the US military did in 2006, when a US Army unit in Baghdad kicked me out of its pool of embedded journalists for writing an article that described how violent the city had become under occupation. Sometimes it is a straightforward refusal to publish a piece — “at this moment I don’t think we are equipped for the response we might get” was how the editor of Emergence Magazine ultimately turned down a piece about Israel’s genocide of the Palestinian people, which had already gone through the magazine’s copydesk and which eventually found a home in Agni. (The genocide in Gaza is the defining moral issue of this time, a wakeup call and a litmus test.) Sometimes it comes with a coercive exclamation mark at the end: “As a quick ed note for the sponsored issue, colonialism is just a bit of a large topic to surface and try to address in a paragraph or two, as I’m sure you understand!” wrote the editor of Nautilus in response to my editor’s note for the Ocean-themed special issue I had commissioned and edited. (The issue went to print without my note.) And sometimes it comes as a thinly veiled intimidation letter from an organization whose job it is to uphold and protect the writer’s work.

On March 4, I received an invitation from PEN America to moderate a panel during the annual PEN World Voices Festival (April 30-May 3, 2025). Like many other writers, I am boycotting PEN America for its failure to support Palestinian writers and journalists, and its refusal to condemn the United States funding the genocide in Gaza. I responded to the invitation accordingly, explaining that PEN’s behavior was an unforgivable dereliction of its own mission.

“The organization’s leadership has continuously refused to meaningfully engage with calls for accountability,” I wrote. “I understand that this has to do with the fact that PEN America’s Deputy CEO and Chief Legal Officer, Eileen Hershenov, is a former Senior Vice President for the Anti-Defamation League, an organ of supremacist propaganda that for decades has worked to normalize the genocidal ideology of Zionism.”

My responsibility as a writer and a teacher is to lead by example, so I posted my letter on social media. Two days later, I received an email from Clarisse Rosaz Shariyf, PEN’s interim Co-CEO.

“We cannot tolerate the spread of misinformation and personal attacks targeting individual PEN America staff members,” she wrote. “The statement in your letter and posted on social media about my colleague is false, based solely on association with another organization without knowledge of her views, and simply unacceptable.”

I had made no false statements about Ms. Hershenov: her affiliation with the ADL appears in my letter exactly the way it appears on PEN’s website. (Which also states that she “plays a key leadership role in guiding policy development.”) My personal opinion about the ADL, the Zionist organization that recently defended Elon Musk for throwing a Nazi salute — not about Ms. Hershenov, whom I do not know — stems from decades of experience, including covering the Second Intifada in 2002, when I worked as a war correspondent. But that is beside the point.

As a Soviet Jewish kid for whom books, often smuggled illegally, constituted the world entire; as a young journalist in post-Soviet Russia; as a war correspondent covering conflicts in Europe, Asia, and Africa I had thought of PEN America as a beacon of social justice. Now, as a writer based in the United States, I am watching it consistently fail to use its mighty and important voice to condemn the genocide, or even use the word. On a personal level, this is, plainly, a great disappointment. But in the broader scheme of things, the letter from Ms. Shariyf denotes something much more sinister.

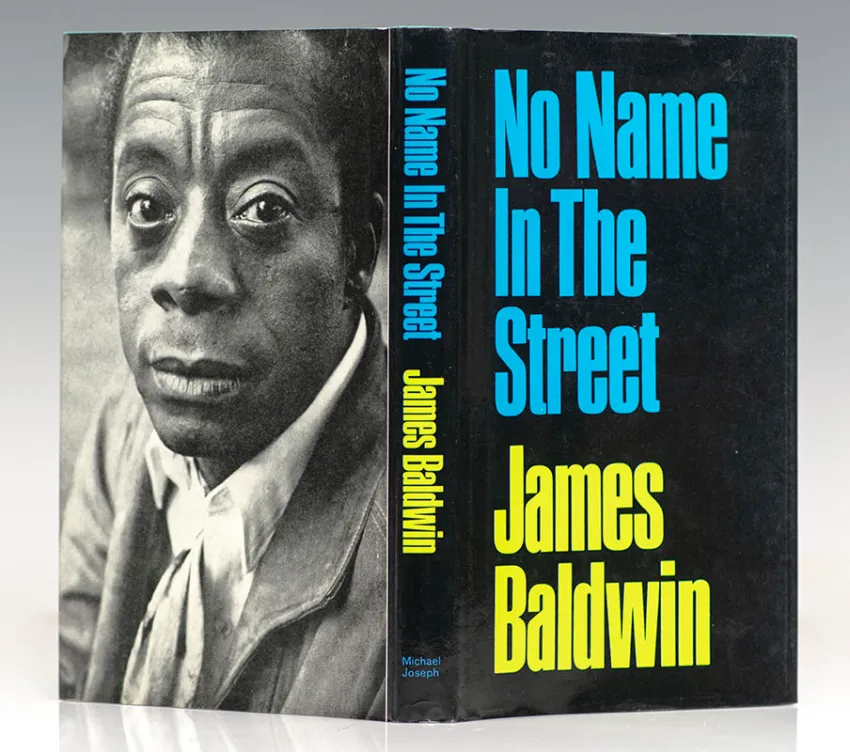

As a writer, I am necessarily a student of history, and since amnesia seems to be contagious even among colleagues whose work is supposed to protect mine, let us rely on a literary ancestor to recall that this country has been here before:

“I returned to New York in 1952, after four years away, at the height of the national convulsion called McCarthyism,” James Baldwin writes in No Name in the Street:

…it was a foul, ignoble time: and my contempt for most American intellectuals, and/or liberals dates from what I observed of their manhood then. I say most, not all, but the exceptions constitute a remarkable pantheon, even, or, rather, especially those who did not survive the flames into which their lives and their reputations were hurled. I had come home to a city in which nearly everyone was gracelessly scurrying for shelter, in which friends were throwing their friends to the wolves, and justifying their treachery by learned discourses (and tremendous tomes) on the treachery of the Comintern. Some of the things written during those years, justifying, for example, the execution of the Rosenbergs, or the crucifixion of Alger Hiss (and the beatification of Whittaker Chambers) taught me something about the irresponsibility and cowardice of the liberal community which I will never forget.… the truth is a two-edged sword—and if one is not willing to be pierced by that sword, even to the extreme of dying on it, then all of one’s intellectual activity is a masturbatory delusion and a wicked and dangerous fraud.

On December 29, 1999, I did have a toddler at home, and I did go to check on my child, and then I filed my story, which celebrated that a modicum of justice had been served in a corrupt, struggling country run by oligarchs and their puppet president. Two days later, the president stepped down, yielding the Kremlin to his latest prime minister, a little-known former KGB colonel named Vladimir Putin. The rest, as they say, is history.

For nearly 30 years, writing has been my life, my responsibility, and my obligation to the world. It is my job as a writer to call out iniquities so that we may work to improve the world we are co-creating. Another thing they say about history is that it does not repeat itself: it rhymes. I am a writer, not a seer, I cannot foretell how the United States’ latest fall into the abyss ends, or when, or even if. But I do know that the moral bankruptcy of American intellectuals and/or liberals who, in Baldwin’s words, throw friends to the wolves will only kick us down the hole deeper, faster. PEN America must do better. Trump and his cronies will act according to their fascist script — but we don’t have to.