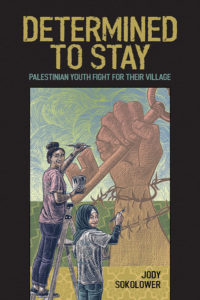

Determined to Stay by Jody Sokolower

Interlink/Olive Branch Press 2021

ISBN 9781623718886

Mischa Geracoulis

Part travelogue, part journalism, and part educational primer, Determined to Stay is Jody Sokolower’s contribution to the Palestinian right to self-determined existence.

A social studies teacher based in California’s progressive, multicultural San Francisco Bay Area, Sokolower had always thought of herself as aware, even critical of, Israel’s treatment of Palestinians. However, it wasn’t until after she and her students saw Promises — a film that examines the Palestinian-Israeli conflict from the perspective of children living there — and then met participants from Seeds of Peace (the American peace-building summer camp that brings Palestinian and Israeli youth together), that Sokolower realized there was still much to know. As her students’ many questions begot more questions, Sokolower determined that answers could only be found in Palestine. Thus began her seven years of travel to Palestine and Israel, the results of which are encapsulated in Determined to Stay.

In the foreword, Nick Estes, Assistant Professor of American Studies at the University of New Mexico, and member of the Lower Brule Sioux tribe, writes of colonizer-oppressor parallels between First Nations in the United States, and Palestinians in and around Israel. Having advocated in places like Standing Rock and the Navajo Nation, Estes understands that where there’s occupation, there’s also resistance. He suggests that occupation renders citizens “foreigners” in their homelands, and he asserts that discourse on any one occupied land cannot be to the exclusion of others. Estes calls Determined to Stay fundamental reading for students of all ages (p. 5).

As an educator Sokolower’s commitment to teach on such consequential matters as the Jewish Holocaust and genocide of American First Nations, serves as rationale to also teach on Palestine. Her book illuminates the realities of contemporary Palestinian life through personal accounts and interviews, and with particular attention to the youth. This book thus becomes an urgent appeal to other American teachers and students to learn the realities on the ground in Palestine and Israel.

Focusing on her visits to the East Jerusalem Palestinian neighborhood of Silwan, Sokolower first situates the region historically. Long considered the “breadbasket of Jerusalem,” Silwan is known to have been inhabited for approximately 7,000 years. As the United Nations explains in its Question of Palestine, “East Jerusalem is recognized as an integral part of the Palestinian Territory occupied by Israel since 1967.” Though Palestinian according to international law, Israel claims this territory for itself and incentivizes Jews to move in, not unlike strategies previously used in the United States to confiscate Native American lands (p. 23).

Many of Sokolower’s discussions with Palestinians pertain to their children’s ability to attend school amid violence and the criminalization of youth. Zakaria Odeh, executive director of the Civic Coalition of East Jerusalem, makes clear that the problem is due to years of Israeli actions in the occupied territories, including continual arrests of children and students, revocation of Palestinian residency in East Jerusalem, land and house confiscations, demolitions, Jewish settlements, military checkpoints, restrictions, and barriers imposed on Palestinians (p. 137).

Approximately 80,000 Palestinian Jerusalemites live outside the city walls, and though they hold Israeli-issued identification cards, all must pass through checkpoints every day. This includes students and teachers, any of whom can be denied passage at any given moment. Children under the age of 18 are often targeted for arrest (p. 139).

Learning of the arrests and re-arrests of children, the physical and psychological abuses that they suffer, and frequent interruptions in their education, Sokolower recalls one of her African American students in California. Her student had intimated that every one of his male family members had been imprisoned, and he worries that no matter how careful he is, he too might end up in prison.

In her seven years of meeting many of Silwan’s youth, Sokolower reports having never met a boy older than eight who had not been arrested at least once (p. 15).

Sokolower relays conversations with a university student, who against all odds, was working on a master’s degree. The labyrinthine journey that prolongs the student’s several-kilometer trip to campus from minutes to hours is the main obstacle. Asking if the student considers moving someplace else where it might be easier to study, she replies, “Despite everything, I’m in love with my city! I can’t live outside of Jerusalem” (p. 170). Conceding to a life too untenable would be exactly what the Israelis want, anyway. They want the Palestinians to leave (p. 171).

Each person Sokolower has met throughout her seven years of travel to Silwan has asked her to promise to tell their story. Many also asked that she advise Americans to think more critically when consuming media reports on Palestine and Israel, to ask questions, and not blindly support the government of Israel. Although it is a full UN member and signatory to the 4th Geneva Convention, “Israel has never followed UN resolutions, and the rest of the world has let them deny our rights” (p. 99). Determined to Stay is a fulfillment of her promise, and as co-coordinator of the Teach Palestine Project, Sokolwer also aims to get more curriculum on Palestine into American schools.

Since Sokolower’s last trip in 2019, the COVID-19 pandemic has multiplied the hardships in Palestinian lives. During a phone call in 2021 with Sahar Abbasi, educator and program director at Silwan’s Madaa Creative Center, Abbasi affirmed her faith in the youth, and commitment to their education. “They deserve to have their future. This is what keeps us fighting” (p. 222).

Sokolower succeeds in chronicling Palestinian experiences with humility, always conscious of her white Jewish American privilege. She manages to translate complex and important information into comprehensible text. Though harsh brutalities necessarily fill many of these pages, the Silwanis’ determination to hold their ground comes through loud and clear.