Aren’t wanton attacks on hospitals and other medical facilities considered war crimes? The coauthors of Human Shields, a History of People in the Line of Fire, Neve Gordon and Nicola Perugini, reveal the shocking truth about military attacks on hospitals, including the Russian Federation’s bombing last week of the hospital at Mariupol, Ukraine.

Neve Gordon & Nicola Perugini

As people around the world were glued to their screens trying to make sense of the Russian-Ukrainian war, a Russian airstrike devastated a maternity hospital in the besieged port city of Mariupol. Reports suggest that the Mariupol complex was hit by a series of blasts that shattered windows and ripped away the façade of one building. Clips from the scene show Ukrainian police and soldiers rushing to evacuate victims, including a heavily pregnant woman who is seen carried on a stretcher amidst burning cars and torched trees. A few days later the Associated Press reported that both the woman and her baby had died as a result of the attack.

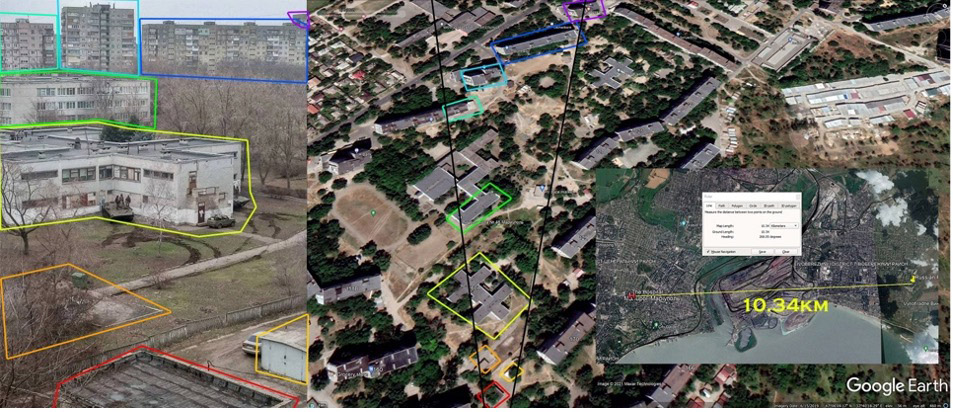

The attack on the Mariupol hospital was only one of 43 Russian attacks against Ukrainian medical units during the first three weeks of the fighting. In an effort to justify such bombardments, Russia has accused Ukrainian armed forces of using civilian structures and medical facilities as shields for military activities. Immediately after the attack on the maternity ward in Mariupol, the Russian Embassy in Israel shared an image ostensibly showing a Ukrainian battalion operating in proximity to the hospital. The image aimed to corroborate the charge that Ukrainian forces are illegally using civilian structures that are protected by the laws of war as shields. It did not take long, however, for the investigative journalist group Bellingcat to verify that the image used by the Russian Embassy in Tel Aviv was of a building actually located ten kilometers away from the Mariupol hospital and that the Russian line of defense was based on fabrication.

Bombing hospitals is not something new in the Russian playbook. Physicians for Human Rights has claimed that Russian forces were implicated in 244 attacks on medical facilities in Syria, where the destruction of the enemy’s health care services became a strategic objective of the Assad regime from the war’s outset. [German broadcaster Deutsche Welle claimed “hospitals across Syria have been attacked more than 400 times. Data obtained by DW suggests the attacks formed part of a larger strategy to cripple access to medical facilities in rebel-held areas.”] In rebel held areas within Syria, the medical field was swiftly pushed underground. Yet even when rebels constructed hospitals in caves, with makeshift emergency rooms, outpatient departments, and maternity wards, the Syrian government, which began receiving aerial assistance from the Russian Air Force in 2015, continued hunting the health professionals down. At a certain point, medical units receiving assistance from Médecins Sans Frontières asked the humanitarian organization to stop sharing the GPS coordinates of their facilities with the Syrian government, a common practice used during war to help protect medical units from attack. MSF realized that instead of guaranteeing protection to these hospitals and staff, at times the coordinates enabled the government and its Russian ally to transform them into targets. With the Syrian regime disregarding the distinction between war-makers and health providers, strikes on hospitals and health professionals became a cornerstone in the military campaign to defeat its enemies.

The attacks against medical facilities in Syria were carried out primarily from the air, and when the Russian air force was blamed with breaching the protections offered by the laws of war to civilians and medical units, officials either denied the allegation claiming that no attack had taken place—fake news—or blamed, as in Mariupol, the rebels for the attack and the ensuing destruction, averring that they were responsible since they had used the medical facility as a shield to defend a legitimate military target such as combatants hiding in one of the hospital wards. The Russian response might sound outrageous to some, but it actually emulates a line of defense adopted by an array of militaries since the inception of aerial warfare.

The Colonial Origins of Hospital Bombing

Hospital bombings have been consolidated as a warfare technique since the beginning of the last century. Not long after Louis Blériot became the first person to fly across the English Channel, European militaries woke up to the significance of airplanes for war. The Italians rushed to acquire a squadron of Caproni planes and, two years after Blériot’s 1909 flight, introduced aerial bombings to armed conflict as they quelled a popular revolt in Libya, their North African colony.

The Italian pilots, who at the time could not fly much faster than 100 kilometers an hour, opened their cockpits over Libya and threw out five-kilogram bombs both at demonstrators and at medical units. In response, the local affiliate of the Red Cross, the Ottoman Red Crescent, sent a cable to the International Committee in Geneva, asking it to “protest indignantly against bombing by Italian airplanes of hospitals marked with Red Crescent flag in Tripolitania.” While the newly established air force continued bombing medical facilities in the colony, Geneva relayed the complaint to the Italian government, asking for a response.

In its reply, the Italian government contested the facts but also requested that protective markings “should be clearly visible on tents, detachments, convoys, etc., so as to make them recognizable even from afar and from the air.” It added that during the fighting, medical personnel should keep a fair distance away from the forces engaged in combat and that in military camps, separate and clearly visible areas should be allotted to hospitals and medical staff. The Italian government declared that it would be unwilling to assume responsibility if such precautions were not observed at all times, for “it could not give up its capability of using all methods of attack authorized by international law, any more than the presence of [medical] units could be allowed to serve as a safeguard for the enemy against its action.” Thus, from the very first instances in which medical units were bombed from the air, the charge that these units were being deployed to shield legitimate military targets was introduced to justify the attacks. Military necessity trumped the protection of medical structures, aid workers and patients.

Proximity

The rules of the game were thus established in Libya. But it was only a few years later, in World War I, that airplanes were for the first time systematically used as instruments of violence. The International Committee of the Red Cross collected eighty complaints relating to the bombardment of hospitals and medical installations by artillery or aircraft. One case that received considerable media attention involved the German bombing of several hospital wards in Étaples on the northern coast of France in May 1918. The medical wards were hit repeatedly, with 182 patients and nurses killed and 643 injured. In one of the raids, a German pilot was shot down, and while being cared for in the damaged hospital he had bombed, he was interrogated about the attack.

“He tried at first to excuse himself by saying that he saw no Red Cross,” one newspaper reported, adding that “when challenged with the fact that he knew that he was attacking hospitals, he endeavored to plead that hospitals should not be placed near railways, or if they are, they must take the consequences.” The pilot’s claim was straightforward: during war, those who help sustain life cannot expect to be protected if they are located in proximity to military targets.

In May 1939, while Britain was preparing for another world war, the attack on medical facilities at Étaples and the German pilot’s claim about why the hospitals were bombed was raised in the House of Lords in London and reaffirmed by a much more prominent soldier. Hugh Trenchard, who had served as an infantry officer in the Second Anglo-Boer War and later helped found the Royal Air Force, which he headed from 1918 until 1930, actually supported the explanation provided by the pilot. He told his fellow parliamentarians that he was aware of the “popular idea” that “every hospital flying the Red Cross is purposely bombed.” “One heard very much the same about the bombing of the hospitals and camps at Étaples during the War,” he continued, “and it apparently did not occur to anybody that the real objectives there were the railway and the dumps.”

Trenchard referred his colleagues to the History of the Great War Based on Official Documents—a chronicle of Britain’s military efforts during the First World War—and pointed out what the director of military operations at the War Office said: “We have no right to have hospitals mixed up with reinforcement camps, and close to main railways and important bombing objectives, and until we remove the hospitals from the vicinity of these objectives, and place them in a region where there are no important objectives, I do not think we can reasonably accuse the Germans.” In other words, the British War Office agreed with the Italian government and the German pilot that a hospital’s proximity to a legitimate military target makes it susceptible to attacks, while also intimating that the culpability lies with those who place the hospital in such a location, not with those who bomb it.

Black Letters

During the Second World War, the intensity of aerial bombings increased dramatically and whole cities were systematically being bombarded, some until they were completely flattened. Indeed, a mere thirty-four years after the first handheld explosives were thrown from a cockpit at Libyan protestors, the United States dropped atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, making the singling out of hospitals moot. In what some have called “total war,” civilian life becomes expendable and bombing medical units is par for the course.

The horrors of World War II led the International Committee of the Red Cross to draft a new convention dedicated to the protection of civilians and civilian infrastructures that included legal clauses aimed at protecting hospitals. Several provisions were adopted obliging warring parties to refrain from attacking medical facilities that display the Red Cross emblem. Civilian hospitals “may in no circumstances be the object of attack, but shall at all times be respected and protected by the Parties to the conflict,” reads article 18 of the Fourth Geneva Convention. The following article, article 19, then prohibits shielding military activities behind Red Cross emblems, noting that the “protection to which civilian hospitals are entitled shall not cease unless they are used to commit, outside their humanitarian duties, acts harmful to the enemy.” The article also prohibits placing medical facilities in proximity to military targets. It reads: “In view of the dangers to which hospitals may be exposed by being close to military objectives, it is recommended that such hospitals be situated as far as possible from such objectives.” International law thus combined the protection of hospitals with the prohibition of using hospitals as shields.

The tenuous nature of these provisions became apparent during conflicts that took place in Southeast Asia immediately following the Second World War. In North Korea during the Korean War in the early 1950s, American and United Nations forces destroyed scores of medical facilities, forcing the Koreans to move their hospitals underground. In Vietnam, the French air force was accused of bombing medical units and evacuation convoys with napalm during the 1954 defeat of the Viet Minh at Dien Bien Phu, to which the French government responded by accusing the Vietnamese resistance of violating the laws of war and “transporting munitions in medical aircraft marked with the Red Cross emblem.”

A decade and half later, the Americans were charged with deliberately bombing Vietnamese hospitals marked with the Red Cross emblem. After the infamous bombardment of the 940-bed Bach Mai Hospital, the United States military maintained that Vietnamese militants had shielded themselves behind the Red Cross emblem, explaining that the hospital “frequently housed antiaircraft positions to defend the military complex,” adding that it was located less than 500 meters from the Bach Mai airfield and military storage facility. The deployment of hospitals to conceal legitimate military targets and their proximity to such targets were thus invoked together as justifications for the attack.

Due to these and other attacks on hospitals, medical units again received significant attention during the Diplomatic Conference on the Reaffirmation and Development of International Humanitarian Law Applicable in Armed Conflicts in the mid-1970s, which led to the formulation of the 1977 Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions. During the conference, the international delegates again outlined the two conditions in which protections offered to hospitals can be forfeited: “The Parties to the conflict shall ensure that medical units are situated as far as possible [from military targets] so that attacks against military objectives cannot imperil their safety. Under no circumstances shall they be used in an attempt to protect military objectives from attack.” In the final version of Additional Protocol I, these conditions were formulated as a form of shielding and incorporated into article 12, which states that “under no circumstances shall medical units be used in an attempt to shield military objectives from attack. Whenever possible, the Parties to the conflict shall ensure that medical units are so sited that attacks against military objectives do not imperil their safety.”

In the wording of the article, we can see that proximity and hospital shielding have a parallel history in international law. The charge that a medical unit is located in proximity to a military target implies that it is shielding the target and can therefore lose its protection under law. It is as if the Italian government’s arguments voiced after the bombing of medical facilities in Libya and Ethiopia became international norms.

In the Midst of Terror

The claim that hospitals were being used as shields became pervasive with the subsequent “War on Terror” and its systematic attacks against mainly brown civilians. From the war in Afghanistan and the US-backed Saudi intervention in Yemen to the Israeli campaigns in Gaza and the Syrian civil war, in recent years hospitals have constantly been bombed by military forces under the guise of counterterrorism, while the shielding argument has been invoked time and again. According to the World Health Organization, in 2020 a medical unit was attacked on average every day, and in 2021 more than two medical units were attacked every single day. Clearly, hospital bombings are neither sporadic nor a series of isolated events but rather a strategy of warfare aimed at weakening the enemy’s infrastructure of existence. And while a few hospitals may have indeed been used as shields, the sheer number of bombings suggests that belligerents use the shielding accusation ex post facto in order to legitimize the strikes.

In Syria it has been primarily President Bashar al-Assad’s regime and its ally Russia that bombed hospitals in rebel-held territories, while in Yemen and Gaza it is Saudi Arabia and Israel whose planes have been destroying medical facilities held by nonstate actors. International and local human rights and humanitarian groups have consistently condemned these attacks, claiming that they are in flagrant violation of international law.

The states charged with bombing medical units either deny the accusation or maintain that the hospitals were shielding insurgents, harboring weapons, or used as a cover for militants launching rockets. In such cases, the bombings do not violate international law, since the law allows militaries to bomb medical facilities that serve as shields, provided that they give adequate warning to those on the ground and do not breach the principle of proportionality.

During the 2014 Gaza War, for example, Israeli strikes destroyed or damaged seventeen hospitals, fifty-six primary healthcare facilities, and forty-five ambulances. In a similar vein, Saudi officials attempted to justify the high number of air strikes targeting medical facilities in Yemen adopted the same catchphrases, accusing their adversaries, the Houthi militias, of using hospitals to hide their military forces. After the bombardment of an underground medical facility in a rebel-controlled area, a Syrian regime official declared that militants would be targeted wherever they were found, “on the ground and underground,” while his Russian patron explained that rebels were using “so-called hospitals as human shields.”

In a September 2019 press conference convened to speak about “numerous allegations of bombings of medical and other civilian facilities in Idlib,” Russia’s permanent representative to the United Nations, Vassily Nebenzia, explained that rebels routinely used medical units to commit acts harmful to the enemy. He thus presented exceptional situations—which according to international law strip medical units of their protections—as the rule, while adding that “the deliberate manipulation of information has become one of the most important weapons of this war.” The Russian presumption was that the opposition will always deny that it was using medical units to advance their war efforts, and thus the debate was shifted from hospital bombings per se, to whether the bombing was legitimate given the legal exceptions.

Such explanations can serve as a robust defense because medical personnel actually lose the protections allocated to them by international law if they “exceed the terms of their mission” or carry out “acts harmful to the enemy” According to the International Committee of the Red Cross, “Such harmful acts would, for example, include the use of a hospital as a shelter for able-bodied combatants or fugitives, as an arms or ammunition dump, or as a military observation post; another instance would be the deliberate siting of a medical unit in a position where it would impede an enemy attack.”

In an effort to legitimize its bombing of Palestinian medical facilities following the 2014 war on Gaza, Israel invoked both exceptions in a legal report. It accused “Hamas and other terrorist organizations” of exploiting “hospitals and ambulances to conduct military operations, despite the special protection afforded these units and transports under customary international law.” It claimed that hospitals were used both as “command and control centers, gunfire and missile launching sites, and covers for combat tunnels” and also as proximate shields for Hamas militants who fired “multiple rockets and mortars within 25 meters of hospitals and health clinics.” Sometimes Israel would call the hospital in advance, warning the staff that it was about to bomb their facility. This allowed the Israeli government to claim that it had provided due warning and reasonable time to evacuate the buildings before it launched a strike, and therefore had not violated international humanitarian law articles requiring belligerents to warn medical units before bombing them.

Following protests by Médecins Sans Frontières against the bombardment of one of its medical units in Yemen, the Joint Incidents Assessment Team of Saudi Arabia’s military coalition released a response similar to Israel’s argument in its legal report on the attack on Gaza: “The [Assessment Team] found that the targeting was based on solid intelligence information. . . . After verification, it became clear that the building was a medical facility used by Houthi armed militia as a military shelter in violation of the rules of international humanitarian law.” According to the self-exonerating report, one of the medical facilities targeted by the coalition “was not directly bombed, but was accidentally affected by the bombing due to its close location to the grouping which was targeted, without causing any human damage. It is necessary to keep the mobile clinic away from military targets so as not to be subjected to any incidental effects.” Even though hospitals had been bombed, the Assessment Team concluded that coalition forces had not violated the law.

The Color Line

Although the legal condemnation of those who use hospitals as shields is unconditional and that act is always considered a war crime, the protection offered to hospitals is conditional. All a warring party has to do in order to legally justify an attack is to claim that a medical unit was located near a target or was used to conceal it, assert that it warned the medical personnel before the attack, and argue that the assault followed the principle of proportionality. The history of bombing hospitals, the legal debates surrounding it, and the formulation of legal clauses pertaining to the protection of medical facilities reveal that international law privileges those who attack over those who shield and can serve as a tool for humanizing the use of lethal force against the very medical units that the law itself purports to protect.

From the advent of aerial bombing, practically every time warring parties admitted they had bombed a hospital (and it was not a mistake), they invoked one of the legal exceptions to justify the act. This history undoubtedly questions the liberal understanding which presumes that juridical processes can replace violence as a way of settling conflicts. This liberal story line, which takes us from violence to law, does not account for the violence of the law itself. Actually, the laws of war do not prohibit violence, they regulate its deployment, providing concrete guidelines about who can be killed, what can be destroyed, and the repertoires of violence that can be legitimately used. The law makes lofty claims about the importance of protecting hospitals but as the history of hospital bombing shows, the law enables and at times even facilitates violence by providing numerous exceptions that allow states to target medical units. Consequently, invoking the law to seek relief from violence is not necessarily the best strategy.

This history thus raises serious questions about the legalistic purview of many human rights and humanitarian organizations, which the legal historian Samuel Moyn has traced in his account of the change from an antiwar politics during the Vietnam War to an increasing emphasis on international law. Referring to the attack on medical facilities in Ukraine, a Physicians for Human Rights researcher exclaimed: “Russia’s brutal history of consolidating power through military action is a clear warning – these horrific attacks on civilians and critical health care infrastructure are a brazen and unambiguous violation of international humanitarian law. The perpetrators must be stopped and must be held accountable for their crimes.” Indeed, accountability for the violation of international humanitarian law has been the primary rallying cry for NGOs seeking justice in Gaza, Yemen, Syria and now Ukraine.

But insofar as legal exceptions legitimating attacks on medical unites are an integral part of the law, the law can end up justifying the bombing of hospitals. This suggests that only a complete ban on targeting medical units, without any exceptions, has any hope of reducing the violence. Once there is a ban, medical units cannot be legally bombed even when they are located close to a military target or when they shield combatants.

The post-9/11 Middle East is the key contemporary laboratory where the “hospital shielding” argument has been deployed to justify the bombing of hospitals. In our book on the global history of human shielding we show how Western liberal democracies have been complicit with the destruction of medical units and the killing of brown civilians. But now, with the attack on Ukraine and the killing of “European people with blue eyes and blond hair,” a different racialized sensibility towards civilian casualties than the one we have been witnessing during the last two decades is emerging. Western commentators seem much less inclined to accept the same legal arguments that had been used to excuse the destruction of civilian sites in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, or Palestine. The speed by which the International Criminal Court decided to open an investigation into possible war crimes carried out in Ukraine is an indication of this trend and is difficult to explain without taking into account the “color line”—to say it with W.E.B Du Bois. Indeed, the Western response to the Russian aggression on Ukraine further reveals how our sense of humanity is intricately tied to race and has never overcome its colonial imprint. But now that the hospital shielding argument has “returned” to Europe after many decades, people might be more critical of the shielding excuses voiced by warring parties as they try to legitimize the violence they deploy against civilian populations.

The time has come to advocate, without distinctions of color, for a total ban on bombing hospitals.