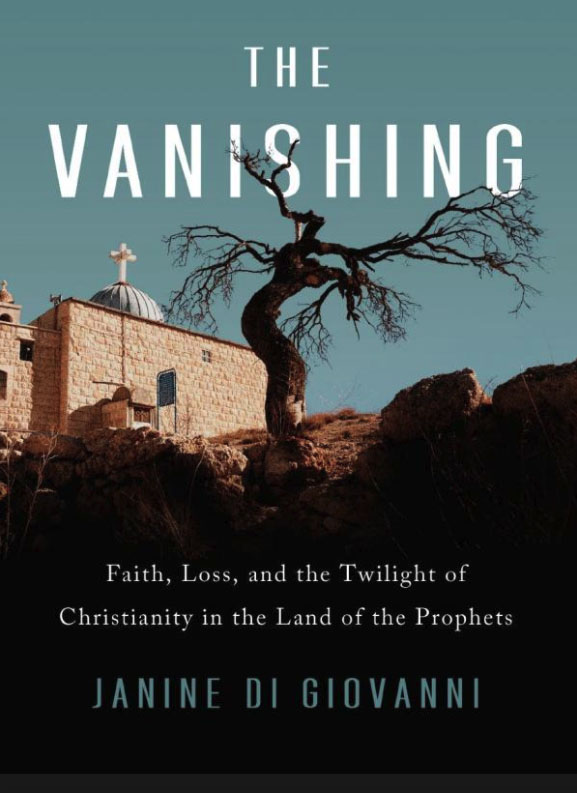

The Vanishing: Faith, Loss, and the Twilight of Christianity in the Land of the Prophets

By Janine di Giovanni

Public Affairs Books

ISBN 9781541756687

Hadani Ditmars

So much of The Vanishing treads on familiar stomping grounds that reading it, for me, was an act of nostalgia. Janine di Giovanni’s evocative portraits of Christians in the Middle East, struggling to survive in a region reeling from war, occupation and dictatorships are close to my heart. From the descriptions of Saddam-era Iraq to an interlude at the ancient monastery of Mar Mattai and interviews with the Orthodox Archbishop of Mosul, who saved the relics of St Thomas from ISIS with minutes to spare; to chats with the Tarazi clan in Gaza, and stories of Syrian and Egyptian believers, the book took me back to old friends and places we’d both encountered over the past three decades of reporting in the region.

But there are inherent dangers in sepia-toned narratives. As the blurb notes:

“The book is a unique act of pre-archeology: the last chance to visit the living religion before all that will be left are the stones of the past.”

While di Giovanni should be commended for bringing to light the stories of the region’s Christians, so often caught between Western agendas and Islamic extremism (often supported by those same agendas), her depiction of Christians as inevitably disappearing from the region overlooks current on-the-ground realities for the “living stones” (as many Palestinian and Iraqi Christians call themselves)

As I read The Vanishing, divided into four chapters simply called: Iraq, Gaza, Syria, Egypt, I received a WhatsAp call from a friend in Bartella, the ancient Assyrian town in Iraq’s Nineveh Plain. He had escaped with his family in a hearse — lent by the local Orthodox church — minutes before ISIS arrived in 2014, and after several years of displacement, had returned in 2018 to rebuild his home. Today he works for a Christian NGO and is currently sprucing up the local state-run kindergarten.

In the neighboring Catholic town of Qaraqosh (like Bartella also mentioned in the book), a young poet I know — who is still basking in the warm glow of the Pope’s visit — wrote to tell me of his upcoming marriage and new teaching job. Meanwhile, the Christian population in Erbil has tripled since 2014 — as the Chaldean Catholic Archbishop who hosted the Pope last spring told me recently, since that papal visit to Mosul, Christians are beginning to return to Iraq’s beleaguered but resilient second city. Even the security guard at the Al-Nuri Mosque, being restored by UNESCO after being blown up by ISIS, is a Christian.

A recent chat with Souhaila Tarazi, the feisty director of the Al Ahli Anglican Hospital in Gaza bombed in last May’s IDF offensive, whose surgeon cousin di Giovanni interviews, was surprisingly hopeful. Moreover, Syrian Christian refugees are beginning to return to their villages. Lebanon, which has the highest percentage of Christians in the Arab world, was not included in The Vanishing, nor was Jordan, where Christians form almost six percent of the population and often hold public office (like my distant Orthodox cousin, Asma Khader, a former Minister of Culture).

This in no way undermines the sobering statistics of dwindling Christian populations in the region whose plight the book dutifully documents, nor the ongoing presence of various extremist groups. But the book might have benefitted from a few more examples of the many tenacious communities in the region who are turning adversity into opportunity. We’ve seen some of this tone before, in books like William Dalrymple’s 1997 tome, From the Holy Mountain: A Journey in the Shadow of Byzantium, billed as “a stirring elegy to the dying civilization of Eastern Christianity.” The Vanishing bears some similarities to The Holy Mountain, which, instead of di Giovanni’s journalistic memoirs, follows the path of the monk John Moschos and his pupil Sophronius the Sophist, who trekked through the Byzantine Empire in the late sixth and early seventh centuries. Dalrymple predicts that his retracing of the monks’ journey that takes him through civil war in Turkey, post-war Beirut, a simmering, occupied West Bank and an Islamist insurgency in Egypt, will allow him “’to do what no future generation of travelers would be able to do” — “witness what was in effect the last ebbing twilight of Byzantium.”

Dalrymple overstated his case, though writing with dark humor — a quality often shared by the likes of Iraqis and Gazans — while di Giovanni takes a more reverent approach in The Vanishing. Her account is indebted to previous women journalists who made perilous treks across the region, like Freya Stark, whose 1937 Baghdad Sketches remains a compelling travelogue classic, with its themes of sectarian strife and women’s rights still relevant today.

One wishes the author had quoted a myriad of Arab poets and writers, however, rather than summoning Europeans like Stark or Karen Blixen (“All sorrows can be borne if you put them into a story or tell a story about them”). Di Giovanni’s conclusion that, “…their faith is more powerful than any of the armies I have seen trying to destroy them” could be the theme of Ben Hur or The Robe — Hollywood epics she cites as early childhood influences.

While the stories of the countless refugees and displaced whom di Giovanni has interviewed over the years are moving, it’s her personal recollections about her early career that are often the most poignant. In the Gaza chapter she recalls being young and scared and being fed sweets by a sympathetic hotelier, whom she meets again decades later, successfully linking her personal sense of nostalgia with the dashed dreams of the First Intifada:

“Years later, back at Marna House for the first time since, my request for Radwan yielded an old man, smaller than I remembered but with the same tremendous shock of hair (though now gray). He remembered everything: friends of ours who had been killed or died, the old dining room—the hotel had been remodeled entirely—and the early hopes of the first intifada.

“I sat in his garden for an hour, drinking a lukewarm Pepsi, remembering, seeing my younger self, trying to recall how I had first seen Gaza, through fresh eyes. When it came time to leave, I hugged Radwan goodbye. He stood in the garden waving. My throat closed with emotion. So much time had passed.”

The Vanishing features so many interviews culled from different periods of di Giovanni’s reporting that the parade of momentary personalities can become a rather confusing blur. Just when one subject seems interesting — like the Coptic man in rural Egypt who reveals he’s been banned from his own church for protesting his house being burned down by extremists — he, well, vanishes, and we’re off on another snippet of reassembled reportage. If this book ever becomes a film, it might be described as Altmanesque.

The Syrian chapter contains some compelling interviews, including one with a Syrian Armenian now living in California, and some interesting history about the Christian connection to Baathism. Di Giovanni rightly connects the recent exodus of Christians to the disastrous Anglo-American invasion of Iraq in 2003, and via an Armenian refugee she talks to, notes that as Iraqi refugees poured into Syria (before the situation was reversed after 2011) Assad “himself was radicalizing Muslims to send them to fight the Americans in Iraq.”

She writes of “inter-generational trauma” connecting the dots with the Ottoman era Armenian genocide but doesn’t mention the concurrent one of Assyrian and Arab Christians (the very one that my ancestors fled). Certainly the entire Christian narrative of the Middle East cannot be recounted in one volume, but here the author downplays differences between Catholic and Orthodox Christians — doctrinally, politically, and historically distinct throughout the region — and even conflates them.

The final chapter on Egypt offers a more complex thesis, presented via a blogger and performer named Big Pharaoh and an interview with a young Christian garbage collector (though never quite resolved), proposing that the persecution of Christians is based more on class than faith. Here di Giovanni makes some astute political observations and offers interesting historical gems, including a mention that the Revolution Flag of Egypt from 1919 bears a crescent and cross to demonstrate that both Muslims and Christians supported The Egyptian Nationalist movement against the British. There is also a fascinating account of Sadat’s banishment of the Coptic pope and a subsequent deal with Mubarak. On page 203, di Giovanni notes that “The Brotherhood, for all their grassroots support, were no match for the ancien regime, which simply bided its time.” She later quotes an Egyptian she interviewed who says of Morsi’s short-lived regime, “They sold out the secular opposition and joined the military camp. But the military camp played them.” And via another interview she relates that ISIS wants to embarrass SISI (Trump’s “favorite dictator”) to show he is unable to protect the Copts.

There’s some lovely description of churches wrapped in the Egyptian flag at Christmas time, to show, says yet another Egyptian interview subject, that worshippers are “Egyptian first and then Christian.” And di Giovanni, who in addition to impeccable war zone credentials also studied fiction at the Iowa Writers Workshop and graduated with a degree in comparative literature from the University of London, offers some elegant phrases in the two personal essays about life under lockdown that book end The Vanishing. Throughout she emphasizes that the situation for Christians in the regions she documents is inexorably tied to the fate of Muslims and other faith groups, paraphrasing what the Iraqi Chaldean patriarch Raphael I Bidawid once said: “When the bombs fall, they are not especially for Christians or for Muslims. They’re for everyone.”