The 3rd edition of the Ramallah Art Fair takes place at Zawyeh Gallery in Ramallah, through Feb. 12, 2023.

Malu Halasa

The Israelis knew the power of art in Palestine. In the 1970s and 1980s, there were no official galleries, and artists showed their work in schools, churches and town halls. The popularity of these exhibitions among ordinary Palestinians also drew an unexpected audience — Occupation authorities. Artists became another front in the resistance. They were forced to apply for permits to exhibit work; their art was censored and Israeli soldiers conducted studio visits.

Before the Oslo Accords in 1993, some artists were imprisoned because they incorporated the colors of the banned Palestinian flag — red, white and black — in their artwork. [On May 13, 2022, Israeli police attacked the funeral procession of slain Palestinian American journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, nearly causing mourners to drop her coffin as they seized Palestinian flags. ED]. However, occupation, discrimination and violence were opportunities not so much for the art of resistance symbols predicated on the fist or the gun, but for art that was modern, complex, critical as well as beautiful.

As stated on the Zawyeh Gallery website, director Ziad Anani believes in “investing in creativity and artistic talents in Palestine as a way of resilience in the face of adversaries.” His West Bank city gallery is host to the third edition of the Ramallah Art Fair until February 12, 2023. The fair features over 200 works by 40 Palestinian, Arab, and international artists.

“Over the years, we have developed a wide and varied network of Palestinian young artists, both in Palestine and abroad,” he writes in an email. “In group exhibitions such as the Ramallah Art Fair, we aim to break the barriers between young and established artists.” The Fair, also available as a 3D virtual online exhibition, transverses geographical boundaries like checkpoints, and allows people no matter where they live to view the artworks.

An independent visual arts gallery, Zawyeh was founded by Anani in Ramallah, in 2013. The first Ramallah Art Fair in 2020 opened during the pandemic when Ramallah was still under curfew. That same year the gallery opened a second hub in Dubai. In addition to the Ramallah Art Fair online, it is also showing another exhibition, Jerusalem: City of Paradoxes by Hosni Radwan until the end of December, online.

“We focus on Palestinian art production,” stresses Anani, “but also we give space to artists who produce art about Palestine, or who are in solidarity with Palestine.” As a Palestinian he said he would “love to see a Palestinian museum of contemporary art. But this is difficult to attain under occupation. Therefore, the Palestinian collections of contemporary art remain in exile the same as the Palestinian artists themselves.”

Sliman Mansour (b. 1947, Birzeit, West Bank, Palestine) is Palestine’s best-known artist. His work spans fifty years and has been collected by the British Museum; Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris; Barjeel Art Foundation, Sharjah; Guggenheim Abu Dhabi; and Khalid Shoman Collection/Darat al-Funun, Amman, Jordan. He was key to the development of Palestinian fine arts education, as the co-founder and director of East Jerusalem’s al-Wasiti Art Centre, and a founding member of Ramallah’s International Art Academy Palestine.

In Ibraaz, artist Samah Hijawi quoted Mansour from Hiwar al-Fann al-Tashkeeli. The older artist commented on the personal journey he had made from political symbolism to art: “ … As you know we have been in the Occupied Territories for 25 years or more . . . Throughout this time we would draw bars, fists, prisoners, confiscated lands and barbed wire through which we developed an encyclopedia of symbols …” Mansour was speaking at a 1993 symposium for Arab artists hosted by Darat al- Funun. “After twenty years or so we started to feel that something was missing in us … and the Intifada in 1980 made me personally feel small and without the importance I had imagined as an artist leading masses to revolution … My work did not have any meaning in light of the Intifada … This granted me a feeling of freedom, through which to develop my own work as well as Palestinian art.”

In 1998, Mansour received the Prize for Visual Arts at the Cairo Biennale and the Palestine National Award for Visual Arts. He was also awarded the UNESCO Award for Arab Culture in 2019. Writing in Imperfect Chronology: Arab Art from the Modern to the Contemporary – Works from the Barjeel Art Foundation, curator Omar Kholeif calls Mansour’s work “iconic” and “a symbol of Palestinian resistance, melancholy and ambition over the past forty years.”

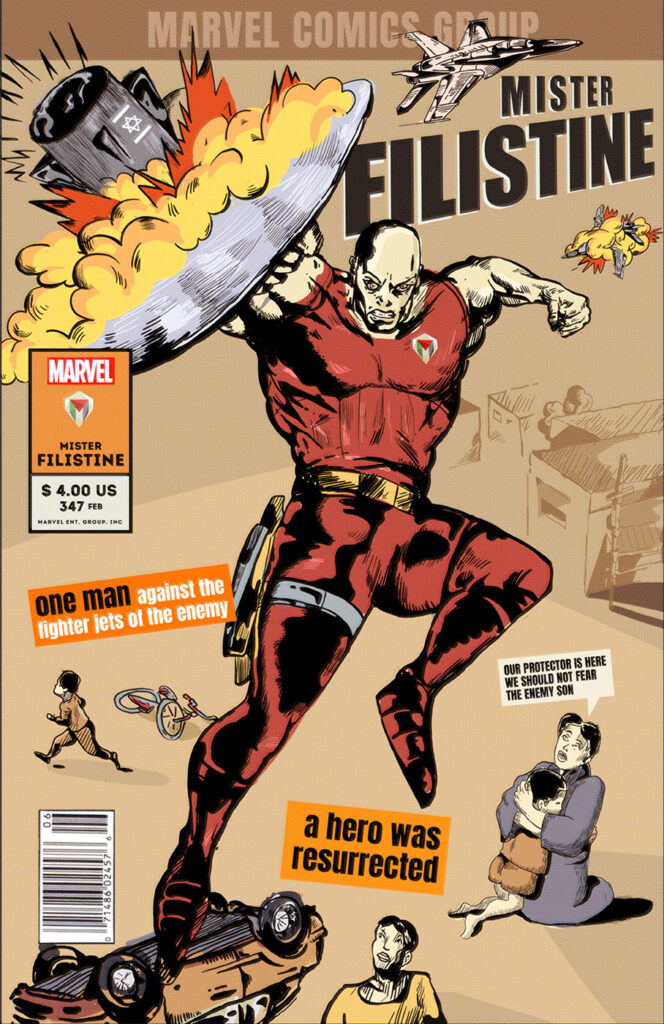

Born in Gaza in 1986, Saher Nasser rebels against “dominant metaphors, established symbols and the power of authority.” These words from his 2021 solo show at Zawyeh Gallery, Dubai, define his art. A graduate of the College of Applied Art, Palestine, he studied illustration at University of Hertfordshire, in the U.K. In addition to commissions by Alserkal Avenue; DIFC; Emaar Foundry; and BMW — all in Dubai — Nassar participated in a 2018 group exhibition at Tashkeel Hub Gallery, Dubai. Since 2015, he has been a member of the art space, Tashkeel, which describes the artist’s creative practice as the point where “social observation and self-interpretation” intersect with art and design. The artist lives and works in Dubai.

Majd Masri (b. 1991, Jerusalem) is an abstract artist, who in 2016 participated in Young Palestinian Artist of the Year at London’s Mosaic Rooms. In an email she writes of her “love of the sea and the idea of us Palestinians in the West Bank who can’t be close to the sea. We’re always surrounded by checkpoints and need permission to enter the other side of our cities. I’m one of millions who is looking for ways to escape this reality and another way to express these feelings of lost, limited chances.” In “Hidden 2,” she reflects “the sea sounds and waves in color in the painting, and finds the blue sky a reflection of the compensation I’m looking for. In abstract work without objects or figures, mass and emptiness leaves space for the person looking at the work to ask questions and possibly find solutions.” A drawing from her series “Haphazard Synchronizations” (2017) graced the cover of my novel, Mother of All Pigs. Masri won second place in the 2018 Ismael Shamout Prize for Visual Art at the College of Arts and Culture of Dar al-Kalima University, in Bethlehem.

Born in Jerusalem in 1993, Yazan Abu Salameh has taught art at several community centers, including at Aidya Refugee Camp in Bethlehem. He studied fine arts at Dar al-Kalima University, and participated in group exhibitions in Palestine, Jordan and the U.A.E. He won the third prize in “Let’s Make It Glow,” a 2019 exhibition held by Turin Municipality, in Italy. He has exhibited in the Ramallah Art Fair, in 2021 and 2020. Art Dubai recently characterized his art as an exploration of “urban geographies … depicting what can be seen as miniature maps that reflect the remnants of childhood memories, concrete blockades and watch towers, as well as Palestinian neighborhoods from a bird’s eye view.” In 2021, Salameh’s solo exhibition was held at Zawyeh Gallery, Dubai. He lives and works in Bethlehem.

Nabil Anani (b. 1943, Latroun, West Bank, Palestine) is a prominent artist and an influential proponent of the contemporary Palestinian art movement. Born during the British Mandate, he lived through the Nakba firsthand. He witnessed the 1967 Six Day War from Egypt, and came of age as an artist in Palestine during the first and second Intifadas. With Vera Tamari and Tayseer Barakat, he established the New Vision Movement, an artists’ precursor to BDS, which boycotted Israeli products and used natural materials — leather, henna and plant dyes — in the making of art. As Dalloul Art Foundation’s Head of Research Wafa Roz writes from Beirut, “From early on, Anani worked to form a modern Palestinian national identity with visual narratives rich in folkloric as well as political themes.” He studied fine art at Alexandria University, Egypt, and held his first exhibition in Jerusalem, in 1972. Anani was a pioneer in the establishment of the League of Palestinian Artists, the International Academy of Art Palestine and the al-Wasiti Centre. He was awarded the first Palestinian National Prize for Visual Arts in 1997. His work has been exhibited widely in the Middle East, Europe, North America, and Japan. He is the recipient of the 2006 King Abdallah II Arab World Prize for Fine Art.

Vera Tamari (b. 1945, Jerusalem) is a multidisciplinary artist, Islamic art historian, curator, and art educator. She is perhaps best known for her 2002 installation “Going for a Ride?” in which she arranged cars crushed by Israeli tanks, during the 2002 invasion of Ramallah, on a piece of tarmac next to the El Bireh football field. From across the street where she lived, the artist watched Israeli tanks stop and their occupants stare at the traffic jam installation of wrecked cars. She told the Guardian a week later “a whole cohort of Merkavas turned up and the tank commanders got out and discussed what to do. Then they got back into their tanks and ran over the whole exhibit, over and over again, backwards and forwards, crushing it to pieces. Then, for good measure, they shelled it. Finally, they got out again and pissed on the wreckage.” Tamari, who admires Duchamp, caught the Israelis in the act on video and turned it into an art happening.

Local pottery traditions, especially large hishash pots made by village women, inspired the artist to open the first ceramics studio in Palestine. She specialized in ceramics, in 1974, at the Istituto Statale d’Arte per la Ceramica in Florence, Italy, after receiving an undergraduate degree in fine arts from Beirut College for Women, in 1966. She obtained a Master of Philosophy degree in Islamic art and architecture from Oxford University, in 1984, and served for more than twenty years as professor of Islamic art and architecture and art history at Birzeit University, where she founded and directed the Paltel Virtual Gallery and the Birzeit University Museum.

Rana Samara (b. 1985, Jerusalem) is an artist and a graduate of the International Academy of Art Palestine, Ramallah, in 2015. A year later for her first solo exhibition, “Intimate Space” at Zawyeh Gallery, Ramallah, she interviewed women in al-Amari Refugee Camp about virginity, sexual desire, relationship and roles. Her second solo show, “Inner Sanctuary,” took place in 2022 at Zawyeh Dubai. Samara has participated in a number of group exhibitions and art fairs locally and internationally, including Contemporary Istanbul, Turkey (2019); Art Dubai, U.A.E. (2017 and 2019); Beirut Art Fair (2017); and Ramallah Art Fair (2020). She told the online magazine Arte & Lusso that she grew up in a typical Palestinian family. “I spent most of my childhood and teenage years observing and analyzing social and gender relations. I came to understand how precious, yet also suffocating, women’s roles as careers and nurturers can be.” Known for her vibrant paintings of interior spaces, from living rooms to bedrooms, Samara explores intimacy in nature for her “Landscape Dream” series.

Bashar Alhroub (b. 1978, Jerusalem) works with a variety of media including drawings, paintings, photography, and video installation. According to his website: His art deals with “the polemics of a place, questioning its role in humanity and its influence on creativity … His work is deeply influenced by the socio-political sentiments that assert [the artist’s] identity as well as his desire to belong to a social and cultural community; rooted in a particular place. Alhroub constantly longs for a feeling of attachment, a sense of significant ownership of that place.” His oeuvre has been included in a number of international collections and museums. In 2001, he received his B.A. in fine art from Nablus’s al-Najah University. He was awarded a Ford Foundation fellowship to pursue his Master’s in Fine Art, which he completed following his graduation from the Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton, U.K. in 2010. His work has been exhibited by the Mosaic Rooms, and he was a resident artist at London’s Delfina Foundation. In 2012 he was awarded the First Grand Prize at the 14th Art Asian Biennial Bangladesh.

Dina Mattar (b. 1985, Gaza) is a painter from al-Bureij, a densely populated refugee camp where judicial assassinations and tank and helicopter gunship incursions, attacks and assaults by the IDF have taken place. Mattar’s paintings are fable-like and bold, as she explained to the Amos Trust. “My use of bright colors is an invitation for hope, optimism and joy. They are an indication that we still exist … My work manifests my insistence and perseverance to exist, and to love life through all that is beautiful.” Mattar obtained her B.A. in art education from Gaza City’s al-Aqsa University, in 2007, and has participated in exhibitions and workshops in Gaza in cooperation with A.M Qattan Foundation and the French Cultural Center. She has exhibited in Lebanon, Geneva and France.

The wide-eyed expression on Mattar’s angel recalls another celestial being — Paul Klee’s “Angelus Novus” (1920) and the words of Walter Benjamin. “The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. The storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back his turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. The storm is what we call progress.” In “Untitled 1,” a poem in Arabic prevents the angel’s wings from closing. “To My Mother” was written from prison by Palestine’s national poet Mahmoud Darwish.

Amir Hazim (b. Baghdad, 1996) is at the forefront of a resurgence of new generation Iraqi artists. As he told Arab News: “Because of everything happening in Iraq now … it’s a great place for an artist to be inspired and explore working in a variety of media. However, since the invasion, many Iraqis don’t see the importance of art and its ability to make a change in the world. We have been pushed away from art. We were distracted by the problems in our country.” Hazim’s multimedia practice merges lived experience and Baghdad’s social history with photography, sound, sculpture, painting, and installation. His photograph from the series “Above the Damage” shows youthful demonstrators on the fringe of the 2019 marches, sit-ins, and civil disobedience against on-going corruption, sectarianism and failing public services in Iraq. Hazim started taking photographs on his phone when he was painting as a student at the Academy of Fine Arts at the University of Baghdad. After graduating in 2019, he picked up a Fujifilm camera and began to explore the medium of photography in earnest. His images play with shadow and light and often appear in cinematic gray-scale. Hazim lives and works between Baghdad and Dubai.

Tayseer Barakat (b. 1959, Jabaliya Refugee Camp, Gaza) is an influential Palestinian artist whose life and art has been shaped by war, conflict and displacement. His family was originally from al-Majdal, a village in the Lower Galilee that was bulldozed by Zionist forces in 1948. He spent his formative years in the Jabaliya Refugee Camp in Gaza. He earned a B.A. in painting from Cairo’s College of Fine Arts, Helwan University, and in 1983, returned to Palestine and taught art at the UNWRA women’s teacher training center in Ramallah. In 1981, he walked for forty days through the West Bank, and solidified his ties to towns and villages erased by the Occupation.

As Dalloul Art Foundation’s Wafa Roz writes, Barakat’s “work is based on extensive research into the ancient arts of the region as a whole, drawing from Canaanite, Phoenician, Mesopotamian and Ancient Egyptian cultures. However, [he] does not adhere strictly to any one style. His practice instead relies on intuition, imagination, and the dynamics of the work itself as it takes shape.” A member of New Vision Movement, he pioneered the use of local media/craftsmanship in fine arts. Barakat was a founding member of al-Wasiti Art Centre in East Jerusalem, and the Ramallah based: al-Hallaj Hall; the International Academy of Art Palestine; and the Palestinian Association for Contemporary Art (PACA). His international exhibitions include the 6th Sharjah Biennial (2003), Institut du Monde Arabe, Paris (1997), São Paulo Biennale (1996), and the Museum of Modern Art (1993). He lives and works in Ramallah.

Khaled Hourani (b. 1965, Hebron, West Bank, Palestine) is an influential conceptual artist, curator and writer. He served as artistic director and general director of the International Academy of Art Palestine. He was also the general director of the Fine Arts Department in the Palestinian Ministry of Culture. He was awarded the 2013 Leonore Annenberg Prize for Art and Social Change — Creative Time, in New York City. In 2014, he organized his first retrospective at the CCA, Glasgow, and Gallery One, Ramallah. He also curated a second retrospective at Darat al-Funun, Amman, Jordan, in 2017.

Hourani was the initiator of the Stone Distance to Jerusalem project and the 2011 “Picasso in Palestine,” a two-years in the making collaboration between the International Academy of Art Palestine and the Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven, the Netherlands. “Buste de Femme” by Pablo Picasso (1943) was, against enormous odds, brought to Ramallah and exhibited to a Palestinian audience, under armed guard. Hourani has participated in many group exhibitions and curated exhibitions in Palestine and abroad. His tongue-in-cheek, “This Is Not a Watermelon,” uses the very colors the Israelis once banned Palestinian artists from using in their art.

Additional information provided by curator Angelina Radakovic at the Mosaic Rooms, in London.

Hermoso el arte el del pueblo Palestino, arraigos y cultura ancestral legado para la humanidad.