With the hybridity of abstract art, Yvette Achkar’s works seem to have abided by the standard that the artist set for herself in a newspaper interview from 1970: “On the outer border, the work will never reveal its mysteries.” She studied in Paris during the same period that coincided with fellow Lebanese artists Shafic Abboud and Elie Kanaan.

Arie Amaya-Akkermans

The exhibition “Taking Shape: Abstraction from the Arab World, 1950s – 1980s” opened at Grey Art Gallery in 2020 and since then the show has also traveled to other institutions in the US. Based on a collection of art from the Arab world at Sharjah’s Barjeel Foundation, the exhibition celebrates the accomplishment of a large cohort of artists from North Africa, Western Asia and Arab diasporas in the West, all of whom worked with abstraction during that fertile and turbulent period. The exhibition’s introductory essay mentions a series of phenomena whose coalescence helped form the movement of Arab abstraction and which complicate easy definitions thereof. These include the exposure to multiple modernisms (primarily European abstraction), in parallel to processes of decolonization, the rise and fall of Arab nationalism, industrialization, wars, mass migrations and the oil boom.

Barjeel’s curator Suheyla Takesh argues that when that precise amalgamation of political conditions in the region came into contact with an influx of ideas from Europe, it spurred artists to try producing abstract artwork that would be relevant in a local context. Exactly how they sought to go about this is harder to pin down. Takesh writes about different sources of inspiration that complicate the genealogy of abstract art in the Arab world: Arabic calligraphy, geometry and mathematics, as well as Islamic decorative patterns or spirituality. But broadly speaking, these influences are not always immediately graspable or historically meaningful.

In Lebanon, for example, Shafic Abboud’s early “hard” abstraction, widely influenced by his training in Paris in the ateliers of cubist artists such as Jean Metzinger and Fernand Léger, later gave way to a more narrative approach of semi-figurative landscapes. Conversely, the artist Saliba Douaihy remained committed, in his later period, to a strict minimalism influenced by Josef Albers in New York, while the trio of women painters Nadia Saikali, Helen Khal and Yvette Achkar continue to be firmly anchored in a language close to color field painting. Many of these Lebanese artists were trained in Western painting both at home and abroad and spent time working in Paris, but they still fashioned for themselves highly personal styles that defy simple classifications and cannot be circumscribed to geographical circumstance alone.

None of these painters was necessarily attempting to rethink the canon of abstract art — Takesh in fact points out that this is a contemporary task, one that cannot be read into art from the past. Nor did they see themselves as either heirs or foes of Western painting, but rather as working in the periphery: Away from the center, but still part of the same language and traditions that were passed down to them not as fully achieved historical forms but as cultural forms still in motion, with all the uncertainties, contingencies and urgent questions of a living, uninterrupted present. Therefore, that “dichotomy” between abstraction and Arab art — a concept in itself suspect and born out of postcolonial nationalisms — can only be a viable hypothesis if European abstraction itself could be regarded as a unified, self-contained and temporally defined movement. But this is hardly the case.

In his 2007 book, Pictures of Nothings: Abstract art since Pollock, historian Kirk Varnedoe, Eurocentric as he was, explains that abstract art has remained relevant into the present because of its hybridity rather than any claims of purity: The opposition between the abstract and the figurative is often unclear, porous and irrelevant. Where others saw a history of libertinism, where rules no longer apply and freedom from tradition is total, Varnedoe found a precision of method: “Abstraction is to be seen more as a history of denials, of self-imposed rigors and purposely narrowed concentration.” Therefore, we have to begin reading abstraction not as a period or a feature of European and later American painting, but as a process and method that can be found anywhere and everywhere, in every period of art history and that could yet take place again.

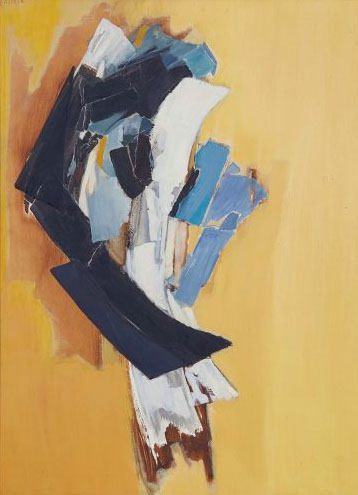

An untitled work by Yvette Achkar, executed around 1980 and displayed as part of the New York exhibition, in fact problematizes the range of the nonfigurative. If you heard a mere description of it, you’d conclude that it has all the formal elements of a color field painting: A large field of bright yellow, intersected by strips of black, white and blue. But in the presence of the actual painting, no description could be more untrue. For one, the field is anything but flat – the background is not so much a pure surface as it is an undulating radiation that fills the entire pictorial space, holding objects and keeping them from losing their shape. The strips of color are not in inert coexistence with the vast yellow field, but have rather been squeezed and reshaped by it, almost stacked atop each other, as though they were heavy sculptural elements now discarded, fragmented, or in the process of unstoppable decay.

The São Paulo-born Lebanese artist, now 96 years old, hasn’t given us many clues throughout her long career to help decipher her inimitable style: Once you’ve seen one of her works, you will always recognize another one, even if the meaning is unknown. But a definition as vague as “abstract” doesn’t help make sense of the ambivalence between the perception of sculptural weight in the painting and the flat planes of color fields and abstract expressionism. In 1989, the artist told journalist Marie-Thérèse Arbid about her hostility towards the concept of the abstract: “This is a stupid terminology. For me, it is a situation in a space which has its own language without known references, the only reference being oneself, the interiority of each person, because nothing comes from nothing and everything already exists.”

This crucial utterance by Achkar, about the inwardness of the artist’s viewpoint, is fittingly emblematic of an artist, who, despite a career spanning multiple decades (she started painting in the late 1940s), and being one of the pioneering figures in Lebanese modernism, remains one of the least studied and exhibited of the artists of that generation. Achkar has never had an institutional survey or a monograph, and she herself has kept mostly silent on the meaning of her work. This is what makes the job of researching her work so difficult, like entering a territory of enigmas.

I first became aware of her a decade ago, having first encountered her works scattered in private homes in Beirut and then in the collections of Agial Gallery and Galerie Janine Rubeiz. After I decided to undertake research on her, I realized that cataloging and tracking her oeuvre down would be harder than it seemed: Nearly all the works are untitled, often undated. The current whereabouts of many are unknown, and most of the galleries that exhibited her work after the 1960s have long disappeared.

A number of paintings would resurface from time to time, in government offices or in private homes, but there was little in the manner of an archive; many had never been photographed and existed only in black and white newspaper clippings or aging catalogs. Her works seem to have abided by the standard that Achkar set for herself in a newspaper interview from 1970: “On the outer border, the work will never reveal its mysteries.” A decade earlier, the late Salah Stétiè, a Lebanese intellectual and poet, who repeatedly wrote about her in this period, said that her work was always “on the border of disintegration.” It is a statement that not only summarizes the difficulty of assigning meaning to Achkar’s work, but also the near infinite density of her large monumental canvases, contrasted with their fleeting presence, appearing suddenly and soon after vanishing in the abyss of time.

I searched auction records, trying to sort through a labyrinth of untitled works from different periods, at least in order to have more elements in the tenuous continuity of Achkar’s work. One such search turned up a painting from 1995 that appeared in a Bonham’s auction from five years ago, with a surprisingly narrative title: “The Sands of Time Behold! Here comes the Horses, Behold! Here pass the Sands of Time.” This title itself encapsulates the chaotic nature of time inside Achkar’s work: Rapid superpositions, violent strokes of sharp color bordered by soft hues, and the restlessness of the material.

Compared to the untitled work from 1980, this work seems more fragile and diffuse, the backgrounds have become softer and more watery, full of transparencies, and sculptural elements of the past have almost completely lost their shape. There’s no doubt about a progressive sense of dematerialization in her work through the decades. In works like the untitled painting from Barjeel’s collection, the superposition and sculptural accumulation is strong, but over the years – though not in steady linear sequence – the interlocked elements became more loose, sometimes concentric, or simply disintegrate.

Back in 1959, more than a decade before her work would reach its mature form, Jean-César Sfeir wrote a short review of one of her exhibitions, the contents of which I have not seen, but that outlines her entire oeuvre: “Yvette Sargologo’s ‘Blue Still Life’ attracts me by the purity of its linear conception and by the uncertainty of the objects depicted. Another still life is in the same vein, but in a different range, sober and warm. The ‘Marine’ is bold and moving due to the reflections and shadows that animate it.”

Sorting through local newspaper clippings spanning the almost half-century between 1959 and 2004 reveals how few people in Lebanon treated her work seriously during this period, routinely classifying it as abstract without any additional qualifiers. There is even this strange rhetorical phrase from 1970, which sums up her approach as “Zen wisdom against mechanistic rationalism.” An essentially meaningless assessment. The artist seemed aware of the situation when she told journalist Jane Gilkey in 1964 that “the people here do not prefer abstract.” Having at the time recently transitioned from object-centric cubism into her particular brand of abstraction, she humbly explained her painting method to Gilkey: “Before I saw a tree (for example), now I paint what lives inside the tree.”

A study of Yvette Achkar’s biography doesn’t clear away the mystery entirely, but it does add details. Born in Brazil in 1928, Achkar came to Lebanon as a child and belonged to the first generation of artists that undertook their education at the newly-opened Lebanese Academy of Fine Arts (ALBA). Fernando Manetti (1899-1964), an Italian artist trained in religious frescoes but familiar with impressionism, taught many of that first generation of artists before they moved on to study other European movements, mostly in France. It was in fact Yvette Achkar’s father, Youssef Achkar, who was responsible for first bringing Manetti to Lebanon. At the request of an Italian colleague, Achkar, who ran a silk factory in Dbayé, pulled some strings in 1940 to help free a young Italian artist who had been detained by the British in a camp in Palestine, where he had gone to make religious art.

The young artist was of course Fernando Manetti, who, once released by the British, came to Lebanon and stayed in a small country house owned by the Achkars. Manetti would remain in Beirut for the rest of his life, teaching art to an entire cohort of young Lebanese artists, including Yvette Achkar, whom he began tutoring from the age of 16.

Despite his lack of commitment to modernism, Manetti would influence Lebanese artists to depart from the stagnant classical realism of the period, introducing vibrant colors, multilayered structures and a fuller range of expression to their work. But it was not until the early 1950s, when Achkar received a scholarship to study in Paris that her personal style began to show itself, consolidating fully around 1970. She was not the first nor the last Lebanese artist to go to the city of light, hoping to hone their style in apprenticeships with established artists. Before Achkar, Omar Onsi and Mustafa Farroukh had both studied in Paris, and her time there would more or less coincide with that of Shafic Abboud and Elie Kanaan.

At that point in the middle of the 20th century, Paris was the undisputed capital of the art world. Students from the global bourgeoisie flocked in to study there from all over the world, bringing in much-needed cash to a city that had been devastated by World War II. Paris became the gravitational center of new modernist and abstract traditions, and the starting point of re-interpretations of painting that spread to all corners of the earth, with particular influence in Western and Southern Asia, Latin America and Africa. It was in fact the birthplace of a global abstraction that was first conceived in the ateliers of cubist, neo-impressionist and expressionist masters, but that then transformed the visual culture of the postcolonial world through unexpected encounters between Western painting and the visual culture of different regions, encounters “facilitated” by a long period of wars, instability, neo-imperial interventions and forced migrations.

We know very little about the details of Achkar’s life in France, except for the fact that she consistently cites Georges Braque and Jean Dubuffet, who were very active in the city at the time, as foundational influences. While Lebanese painters in Paris at the time were experimenting with the formalist aspect of cubism Achkar eventually found herself bored with painting objects, and turned to what Sfeir has called “all the possibilities of surface.”

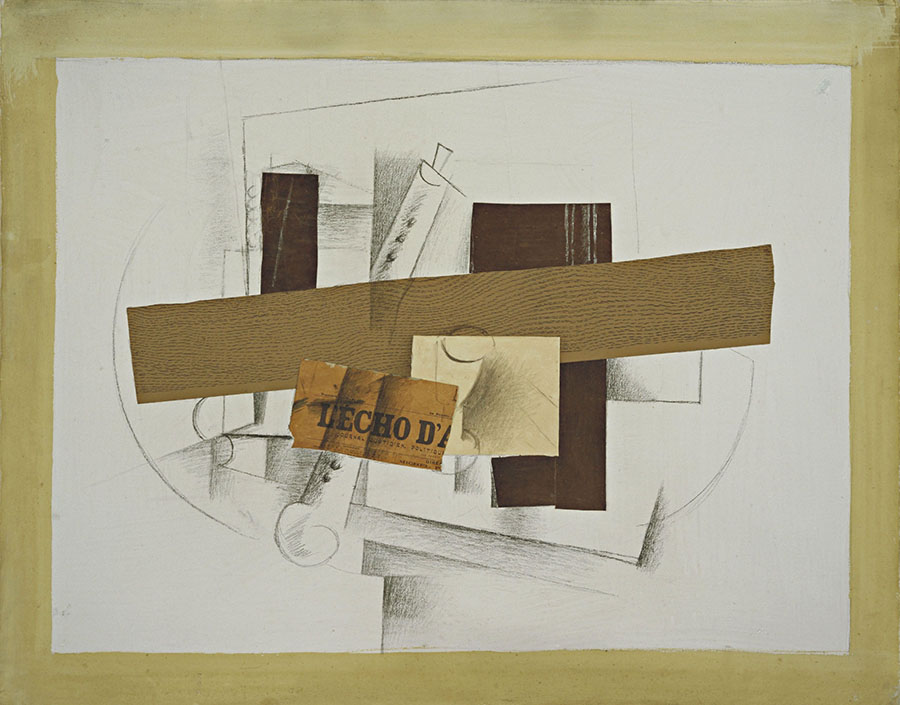

In fact, Braque, together with Picasso, played an enormous role in the development of cubism, and Varnedoe tells us in his book about the confluence between artistic innovation, political events and cultural shifts at the time: “The fragmentation and reassembling of the world effected by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in their Parisian cubism of 1909 to 1914 had allowed, encouraged, even goaded several artists, especially from outlying countries such as Holland or Russia, to push further into a world of forms, leaving behind any trace of reference to recognizable objects or scenes. The invention of these new kinds of abstract or ‘nonobjective’ art coincided with the cataclysm of World War I, and the artists involved explained their innovations in terms of contemporary revolutions in both society and consciousness, proposing in numerous manifestos that their art laid bare the fundamental, absolute, universal truths appropriate to a new spirituality, to modern science, or to the emergence of a changed human order.”

By the time Achkar landed in Paris, Braque himself had moved away from hard-edge cubism and was mostly isolated, overshadowed by Picasso, working on large collage-style paintings that incorporated cubist elements but were grounded in figurative relations. Some of the works that Achkar produced upon her return to Lebanon bear a stylistic resemblance to those semi-figurative works that Braque painted in between the wars.

But there’s another fascinating confluence between their approaches. In a number of works from the Synthetic Cubism period around 1913, such as “Still Life with Tenora,” “Guitar,” or “Bottle, Newspaper, Pipe and Glass,” Braque used the revolutionary technique of papiér collé that he’d introduced with Picasso a year earlier, a style that consisted of using bold geometric fragments of paper interlocked to form an illusionistic composition, foregoing the idea of representation altogether. This period would become the foundation of what was yet to be called color field painting in the 1950s. But in their formal architecture, Synthetic Cubism, using contrasting types of paper to overlay multiple virtual spaces, has an uncanny resemblance with the method that Achkar deploys in her canvases after 1970.

Looking at Achkar’s works from her mature and most prolific period, the 1980s, one can only wonder how a deeply private person like Achkar experienced and processed the cruel years of the Lebanese civil war that raged from 1975 to 1990. In this period of the 1980s, as the violence escalated, her airy backgrounds turned into unforgiving blacks and reds, with very few elements therein and with diffuse centers of gravity.

Under conditions of extreme violence, the person becomes disembodied, waking consciousness and nightmare converge, and the pictorial space becomes a question in itself – how to dwell comfortably in these spaces of daily horror? Unlike many modernist artists, Achkar never returned to Paris, and she spent all the years of the civil war in Lebanon. During these difficult years, she continued painting prolifically and exhibiting regularly in Beirut. Towards the final years of the war, in 1989, she expressed herself briefly in a number of cryptic short texts in French and interviews published in the media, where you can see the intoxicating anxiety of a chaotic time, mixing artistic meditations with personal recollections in a monologue, without us knowing whom she’s addressing: “But tell me a little about yourself, about the others. How did you live through these terrible days?”

In one incredible passage, she talks about the fear that she encountered while painting: “No, I couldn’t paint. I spent my energy trying to not be afraid. Fear, I discovered it this time… It’s an obscene thing that destroyed something in me… I can’t yet define it. I can’t get over this discovery, the discovery of fear, the abject fear… There is something irremediable that has affected us all. I’m completely frozen, completely frozen, yes I’m frozen…. A noise. It’s not a simple movement of air; it’s not just a sound. It’s a language. And the noise is nasty. Very nasty, these noises… So, you will guess that I put the brushes away. Does creativity have any meaning when we discover so many horrors?”

It would be tempting to assume that this is a war testimony, but I think she’s speaking of two different sets of fears at the same time: The fear of the witness to the horrors of war, on the one hand, yes, but on the other, also the fear of the void, of reaching the limits of painting, and falling through a space that can no longer hold any weight; it’s a primeval beginning without any prior images. The painter stands in front of the world before the creation; it is unseen and unformed, without form and void.

In her paintings from 2009, the last time she held a solo exhibition, at Galerie Janine Rubeiz, the heavy elements from 30 years ago are almost completely thinned out. Sometimes they are barely a line, floating aimlessly against white and gray backgrounds, perhaps pointing at her own mortality, and the shrinking of space in general – perhaps both political and emotional. These more recent paintings are lighter but also harder to look at; we feel the instability, the tension, the groundlessness of life.

The interpretation of Yvette Achkar’s work remains an unfinished task, not only because the material is partial and the artist (as well as the critics) are silent, but because part of the nature of her work is remaining unavailable to the viewer. After all, her main subject is not the image but the self itself. In 1989, Achkar described her painting process: “It is like layers of paper placed on top of each other in quantity, you tear them off one by one, to arrive at the primordial which is the self. Remove everything that is superficial to arrive at the center, and the center is once again, the notion of a circle, that is to say life, and fear will say death.” Is this perhaps a final confirmation of her debt to Synthetic Cubism?

Salah Stétiè wrote in that incredibly violent year of 1989 in Lebanon that her work was the search for a pure, fundamental space, but a space without mythology. But how could one want to live without myths in a time of monsters? Yvette Achkar’s question returns today to haunt us, more than 30 years later, during a time of extreme violence: “How did you live through these terrible days?” The artist herself offered a partial answer in 1970, when she found a temporary solution to the fear of the void, through her art: “As you make the world of the Spirit accessible and comprehensible, you preserve this world’s ineffable character, the sense of transcendence, its halo of mystery, the need to rejoin it both through ease and through effort.”

When Varnedoe made the argument for abstraction as a rigorous method, he proposed the idea of abstraction not as randomness or uncertainty but as hypertext, “A better model for abstraction is perhaps the hypertext, where the line between A and B goes out in a million possible and ever more complex directions, where artists along the line from A to B find that A or X is a window opening onto an entire universe.” Accordingly, in the ineffable world of Yvette Achkar, across almost eight decades of painting, the indefatigable search for a final horizon is not a linear narrative spanning from beginning to end, but a near infinite series of spatial operations on the canvas to reveal the absolute, the mysterious, and the indescribable. Yet she’s anchored in the paradox that the end should never be reached, should one want to continue painting until the last painting, until the heart stops, until extinction. One day, the last element thinning out into the background will become a transparent line that finally breaks free. After that, there’s nothing beyond.

Fantastic article on Yvette (MY DEAR MOTHER).

I am her younger son.