A profession that takes advantage of the dead…

Samira Azzam

Translated from the Arabic by Ranya Abdelrahman

His mission comes in three stages. The first starts around six AM, or a little earlier, while I’m still busy hanging up the morning papers on the wooden stand. He comes over, biting into a knafeh sandwich, sugar syrup dripping down his chin, and asks about the news. I insist on cracking a joke that was already stale ten years ago, pointing at the red headlines and saying, “Read it yourself! You can read, can’t you? But pay the quarter before you touch a single one of those papers.” He laughs, the remains of the sandwich showing through his yellowed teeth, and says, “If I read one word outside the column, I’ll pay whatever you want.”

When something becomes a habit, you stop reacting to it. That is, I don’t get angry the way I used to, ten years ago, and I’m no longer disgusted by the way he looks, his cheeks stuffed with food. Without getting too worked up, I open up the two big dailies and point to the obituaries. “Go ahead and read, but don’t touch anything with your filthy hands.”

Not wasting a moment, he takes out an old stub of a pen and writes down the names of the deceased, leaving out only the names of the old women.

Actually, I don’t want to gloss over that last part. It was months before I thought to ask him how he could tell which names belonged to old women. He laughed his sleazy laugh and said, “Come on, Ustaz, every woman who’s done all her religious duties must be old. And people don’t pay a thing for elegies of old women, so I’ve got no business with them.”

If there was a photo at the top of the obituary, he would stare at it, goggle-eyed, and then his sleazy smile would return, spreading across his face. “A young one … a young one…,” he’d say. “The daaliyyah poem will be perfect. It’s been tucked away for a month now. This photo should earn me at least twenty liras, or fifty if I manage to cry. Do you think the name will fit, Ustaz? Never mind, we’ll think about that later — now, open that other paper for me.”

I open it, and he copies down more names. Then he puts the list into his pocket, saying, “And now we’re off to ask for addresses and sort through the poems. We’ll need four: One of the poems will work for two of them. We just need to come up with something for that old man with the strange name. As for the fourth, I’ve got a poem that fits so well, it’s as if it was written for him!”

After that, he leaves me, and this is where the second stage begins. For him, it’s the hardest part. He might have to roam all four corners of the city, stopping in front of every flyer covered in black ink that’s been stuck on a wall or a lamppost, to read the dead person’s full details. If it’s an old flyer, he pulls it off so he won’t waste time checking it again the next day, a task for which, in his opinion, he deserves to be rewarded by the city. Otherwise, what kind of state would the walls be in, if the flyers piled up, one on top of the other?

And if I said, “You pull them off the wall to throw them on the ground?”

He’d answer, “God forbid! The names of the dead are sacred! I gather them up in a stack and toss them into the nearest bin. Come on, Ustaz, we’ve seen charity from most of them, and we still have a little dignity left, you know.”

I study his expression for any trace of dignity, and my gaze gets lost in the lines, which barely move when he laughs or cries. In the folds, little white hairs have sprouted, which he won’t shave all the way off — a well-trimmed beard isn’t part of the grieving look. His features hunch under a shabby tarboush, its tassel having lost most of its threads. This tarboush has a mission not tasked to every one of its kind: Right beneath it, on the sweat-drenched surface of his bald spot, he places the chosen poem, so his fingers won’t pick the wrong one from amongst four or five others. He’s afraid he might get the names mixed up: “We got it wrong once,” he told me, and I tried to catch his meaning through the sound of his breathy laughter, “and … I read a man’s poem for a woman. I’ll never forgive myself for that one. It got me thrown out of the dead woman’s house and cost me the payment I was expecting, plus the ten piasters to get there and back by tram, not to mention that I had to climb 90 stairs! All I got from her family was a Bafra cigarette, which fell out of my hand when I pulled myself free from the idiot who was pushing me. Earning my daily bread isn’t easy!”

Dead people have their virtues distilled into three or four verses, not one of which makes any sense, unless it was stolen from somewhere.

I feel a bit of schadenfreude as I tell him it serves him right, since he’s picked the lowest way to earn his living. He frowns, and I see a flash of pain clouding his faded eyes. “Each of us has his calling.”

If he’s still doing his rounds, he’ll definitely be in front of a mosque or church by now. From the breadth of the family’s preparations, he gets a measure of the deceased’s place in society and he can tell, with amazing intuition, exactly how much he can expect to make. I see him again, when the daytime sun has grown vicious, sitting in the shade on an ancient staircase, digging multiple bits of paper out of the pockets of his green-black suit. With his whittled-down pen, he crosses out names and writes one in place of another. Dead people of every ilk, faith, and age have their virtues distilled into three or four verses, not one of which makes any sense, unless it was stolen from somewhere. It didn’t matter, though — or that’s what he says. The grieving don’t understand anyway; after a day filled with a tumult of emotion, their brains have stopped working entirely.

Actually, from where I sit — and without needing to see him in action more than four or five times — I can tell exactly how he is at a funeral. He might be the only actor in the world who plays a single role for his entire lifetime. At more than one show a night, his bottom lip is called on to quickly start trembling, and then everything about him seems to take on the same quivering motion: his sleeves and his legs, his saggy pants and the button on his tarboush, which has slipped down to the middle of his forehead. He lingers for a few minutes, his shaking unabated. And then, after the sweat has gathered in big drops under his tarboush, he pulls it off, takes a sheet of paper from inside it, and goes over to where the home’s owners are seated. He begins to read, in a defeated voice that is utterly toneless except when he speaks the name of the deceased. The elegy is personal, very personal: he doesn’t care if the name is far removed from its context; he knows how to squeeze it in. When he gets to the end, he wipes the sweat off his forehead and takes two steps forward, clasping the hand of the person closest to the deceased in both of his. By now, a couple of notes have been pressed into his hand, and he nimbly magics them away and takes himself off to his chair, where he allows himself a cigarette. Snatching one from the nearest table, he sniffs the tobacco through its unfiltered tip, keeping it unlit so that, if it’s imported, he can exchange it for two locals the next day.

Now, if someone were to think this was just easy money, then they would be selling the man short in any number of ways. Some people can’t be coaxed into mourning their dearly departed with worn-out words, sucked dry of all meaning. But our shameless friend has skin so thick, no amount of pummeling can penetrate it. Regardless of how the mourners pull at his sleeve, having heard his poem at twenty other funerals, he won’t stop. And however hard they try to push him out, he is perfectly capable of repeating his theatrical entrance a few minutes later. So shelling out was the price of saving themselves from a situation that would disturb their mourning and insult the dignity of the deceased. Some people would offer him the money before he had finished reciting the first verse, but he would refuse to cut his reading short — it wasn’t just the money that breathed strength into his legs, which were plagued every winter by rheumatism. If they forced him to stop, he would weep and tremble even harder as his fingers felt their way into his pocket.

“The Gravedigger” by Karim Kattan

I don’t want to accuse him of setting his sights on me, or to say his blade touched my throat on purpose. I was in my bookshop, bent over some stamp collections with my tweezers, sorting them into little envelopes, when the phone rang. It was the kind of ringing that brings on a feeling of dread and a reluctance to make it stop by picking up the receiver. How could he of all people be dead? And how? Scattered to dust with the remains of a burning plane? I felt my nails dig into the flesh of my palms as I trod in circles like a bull around a waterwheel, until my brother stopped by and pulled me outside, then locked the store and dropped the keys into my pocket.

I used to love that cousin of mine. He was my guide to the city at night, and, without him, stepping outside the confines of my store turned me into a child lost in the market. The news wasn’t in any newspapers or on any posters. Instead, it was announced on all the radio stations and was on the lips of hundreds of people. These were the sort of people who, for a few short hours, would succumb to a philosophizing that put them in the mood of pious humility: if they weren’t the victims, then they needed, at least, to be witnesses. By evening, my uncle’s house was crowded with callers, and I saw faces I don’t remember having seen anywhere before. The air was thick with bitterness and pain, and I had an arm around my uncle’s shoulders, bracing him so he could endure his manly sorrows without collapsing like a tattered rag. Just then, I saw our friend cutting through the crowd. He looked like a wind-up toy as he came in, having been overtaken by a trembling that ran from the button of his tarboush, to his lips, to his sleeves, and down through his pant legs. He sat on a chair, given up to him by a boy from the family, and the plastic contours of his face went through their tragic contortions as sweat began to gather in droplets on his forehead. As he reached out, pulled off his tarboush, and took out the sheet of paper, my arm went slack around my uncle’s shoulder and my hands began to clench and unclench.

I was suddenly on full alert, itching to stand up, incensed by a grief that, in an instant, had turned to rage. I stood and took a single step, then bumped into the table. He was already standing — perhaps he hadn’t noticed me before because, as soon as he saw me, the trembling in his body stopped, his features froze, and a fleeting gleam flashed through his gummy eyes. Reaching unhurriedly into his pocket for a handkerchief, he dried his head with it and fixed his tarboush back in place. He came up to us then, with a bit of purpose in his stride, and kissed me, shook my uncle’s hand, and left.

End Note

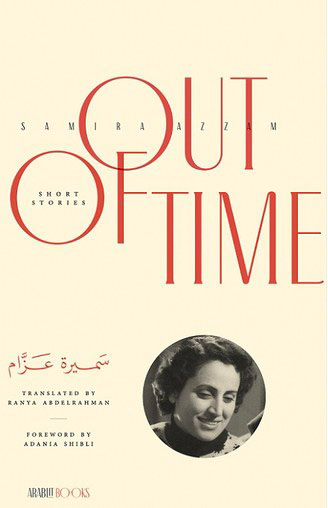

“Tears from a Glass Eye” was originally published in Out of Time: The Collected Short Stories of Samira Azzam (2022). Translated by Ranya Abdelrahman, it was the first ever collection of Azzam’s to appear in English, and appears here by special arrangement with ArabLit.