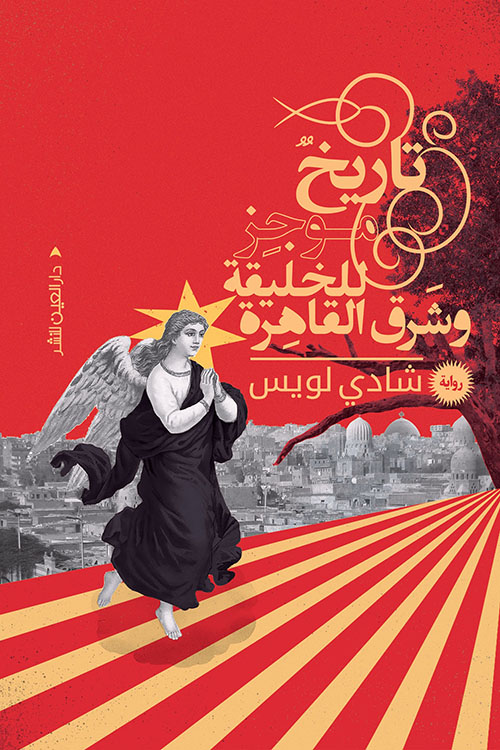

In this excerpt from Shady Lewis Botros’ latest novel, Brief History of Genesis and East Cairo, a child’s innocent counting game masks a disturbing reality.

Shady Lewis Botros

Translated from the Arabic by Salma Moustafa Khalil

Thirty steps exactly between our door and the street corner. More accurately, between our doorway and the corner of Abu Nabil’s house, the point at which our street pours into Street 24. This accuracy, borrowed from the grown-ups’ world, was sufficient to give my game an air of seriousness. I was searching for certainty, reassurance that there was something out there one can truly rely upon. Accuracy seemed one of the few possible sanctuaries in a world filled with doubt. Day after day, and on boring evenings, I would build a strict and detailed map of our area out of numbers — the exact number of steps from one point to another, between one house and the next, one store and the next, the number of steps up and down stairwells, and from curbs to doors. A poem of numbers, for movement and memory. In it, each number meant one and only one specific thing, and the whole map gave me one feeling: tranquility. I could easily walk around in the darkness, with a blind man’s confidence, a security that words rarely ever give, as grown-ups’ promises always prove themselves to be lies.

The numbers game alone could patch up the holes in the unfathomable lives of grown-ups. For in a world that I experienced from below, from the very bottom, without any power whatsoever, it was exhausting to try and grasp it for what it was. With time, my map of numbers became an alternate universe to the one grown-ups lived in, a copy of it, existing within its creases, more accurate and innocent, its dimensions measured, predetermined, and expected, with neither happy nor scary surprises.

“Open your eyes, you’ll fall on your face!”

I had reached number six when my mother snapped at me; she pulled me behind her with speeding steps, carrying the big black plastic bag in the other hand. She dragged me across the sidewalk as I resisted awareness. Stubbornness was all I had left, after having been stripped of everything else.

I locked my eyes shut with the first crashing of her head into the thick kitchen wall. I did not open them even as she dragged me out of the house. I always did that when my father assaulted her. I would close my eyes to everything around me and count. I would listen to the sound of her pain, as consistent as the ticking of a clock. I would count the strikes until her whining turned into screams, how many strikes until her screams for help that never arrived turned into cussing, how many strikes before her damnations turned into a surrendering hiss.

This was my way of hiding while still being with her, as a trusted and cowardly witness. I would curl up into myself in terror and try to escape the shame of letting her down. Children feel shame too, the worst kind of absolutely helpless shame in the face of adults. I recorded everything for her sake, how many strikes before her nose would start to bleed, the slaps required for her upper lip to swell, one or more punches before the black circles under her eyes turn blue. How many strikes with his knee between her thighs before she collapsed, the number of gasps she released as she kicked her legs left and right, her body turning and convulsing before she would lose consciousness and a line of saliva would start making its way from the side of her mouth to the floor. I counted the minutes that had to pass before she would wake up, and her awareness would turn into wailing, her wails to sobs, tears piling onto the floor, slowly forming a direct drain to the silent walls, that witnessed our misery with indifference.

I counted and recorded everything in my memory. Everything becomes more bearable when transformed into a number. Like the reports of deaths on the evening news. Numbers create a safe distance from pain, far enough for the details to become blurry, close enough to clear a guilty conscience. Seven blows, two hundred and twenty missing. Twelve slaps, thirty-nine dead. Two punches, three minutes, two hundred injured. And so on and so forth, until all attempts at endurance turn into adapting, and adapting becomes adjustment, and adjustment turns to neutrality devoid of feelings, which spoil accuracy. With more repetition and continuous auditing, this all turns into indifference, focused on inconsequential calculations, attentive only ever to methodological details.

I carried on counting the steps with my eyes closed. My mother was still dragging me behind her. We reached the end of the road, exactly thirty steps from our front door, as always. I cheered up; the buildings had not moved, the street did not get longer, everything was exactly where it ought to be. We turned right onto Street 24. It was slightly wider than ours, yet identical to it in every other way, except for a video store that displayed posters of a half-naked Nadia el-Gindi and huge pictures of sequels like Rocky II, arousing our half-innocent lust. Around the corner there was a bright white mosque, devoid of any details or decorations. The water fountain next to it was what made it real in the eyes of the thirsty children who played regularly in its vicinity. The sound of the cold stream of water exploding out of its three taps was witness to our childhood. It quenched our thirst. We’d fill up those silver cups tied to the cooler with a rusty chain, reveling in the refreshing smell of the layer of algae that grew around the taps with time.

We took twelve steps down Street 24 until we arrived at its intersection with Mansheyyet al-Tahrir Street. This is the line at which my sense of safety ended. For, this was the first main road we had to cross to exit our neighborhood, and I was not allowed to cross it by myself back then. The traffic on that street was aggressive, unlike on our calm side streets. Crossing from our side to the other meant stepping out of Masaken al-Hilmeyya and onto the edges of Ein Shams, where things can get a little rough. It meant crossing into the unknown, a world we hardly knew and pretended did not exist.

My mother squeezed my palm a little too tightly as she prepared to cross the street. Finally, I opened my eyes. She did not bother looking left or right; the stream of cars never calmed. One after the other they rushed past us, pushing the air and all the dust it carried onto the sides of the road, disregarding those standing and walking on it. My mother froze for a moment, tightening her eyes with focus as if listening to the stream of cars coming from afar, in anticipation and wonder, searching for a moment of hesitation so that she could seize her opportunity. This was the wisdom she had learned from a small life lived under the temperamental mercy of others, always in anticipation, constantly in search of a hole to slip through.

She stepped into the road with one foot, dipping it in for a moment, and a car flew by, causing a tremor in the poorly flattened road under our feet. My mother lifted her leg back up and returned to safety. She repeated this process another time, unsuccessfully. But on the third attempt she sprinted, as if trying to outrun her patience, throwing our bodies into the road. She dragged me and ran with the willpower of a woman who owned nothing but her fragile body, attempting to face the world and delay its revolving wheels even if for just a moment, just one moment where the world acknowledged her existence, even as a potential corpse.

I ran with her through the traffic. It was like a dance in the penalty zone by a player who did not care about scoring a goal, only about being part of the game at all. My body was shivering with the pleasure of taking a risk. A black taxi screeched as it came to a halt in front of us, blowing the final whistle. We had won. The taxi almost hit us, and the truck behind it almost crashed into it. The driver threw his head out of the window and banged on his car door.

“You dirty bitch!”

My mother released a victorious chuckle. She carried on as if nothing had happened, and relaxed her grip on my hand.

“Mama, where are we going?”

Shock covered her face. I did not understand why such an expected and obvious question would cause such surprise.

“Just walk silently! I have enough on my mind!”

We walked seventy-two steps in Mansheyyet al-Tahrir Street until we arrived at one of its corners. Two workers were tearing down the small red-brick walls that stood in front of buildings. My father had told me once that they had been built to protect the buildings behind them from shelling. Bombs, even if they do not hit a building, still cause enough air pressure that would destroy it, if not for those barrier walls. These things confused a child my age. How can air destroy a huge building of brick and steel, and how could this small wall challenge a bomb and save a huge building and its inhabitants from destruction? I was always impressed by my father’s knowledge about war, and the dangerous things that he had experienced and knew about, like all grown-up men.

The workers were causing a lot of noise, surrounded by a cloud of thick dust. We had to stray from our path to avoid the flying debris. I turned to my mother, looking for any explanation.

“Mama, why are they tearing down the wall?”

This time she responded somewhat tenderly: “Because the war ended a long time ago.” It appeared as though the question allowed her to avoid talking about our destination. Her smile encouraged me to ask another question, in search of a guarantee: “And it can never return?”

She seemed preoccupied by her smaller battles; they were closer and more urgent. How to cross the road, our unknown destination, her arm that went numb from dragging around this black garbage bag — and me, her single burden and only source of joy. The bigger wars were the last thing on her mind.

“I don’t know, quit making a fuss!”

We turned right onto Saab Saleh Street. It was a boring, soulless street. Gray five-story residential buildings covered its first half. The more we walked towards Ein Shams, the higher and duller the buildings became, with humidity stains and cracks growing bigger and bigger. They used to say that the street received its name from a Saudi man who had lived on it a long time ago, back when it was still a desert. He had a farm with one hundred purebred Arabian horses, and three pumps for springs from which everyone in the neighborhood could drink.

Whenever I walked down that street, I would distract myself from its mediocre bleakness by envisioning the desert that used to overflow it. I did that a lot, entertained myself by turning the buildings into dunes hiding wonders and caves filled with endless tales. The cars would transform into giant monsters, their roaring a mechanical sound scaring the pedestrians. The ghosts of the Arabian horses would return to roam and race all around us. And the pumps would spray water in every direction, filling the air with a refreshing drizzle, as if walking in a fountain. These fantasies did not last very long. It was one of my tricks to overcome the dullness of the grown-ups’ world, yet with repetition it became as dull. There were no other options left than to return to that world and let go of my pointless daydreams.

We walked down the entire street without my mother saying a single word. It was supposed to be three-hundred and sixty-five steps, but somehow I had miscounted. It was a long street, and I had been distracted. When we arrived at the intersection with Shaheed Ahmed Issmat Street, I was struck by the sight of the big, ugly church around the corner. This church would regularly burn down, about twice a year.

Every time the parishioners would rebuild the church, strengthen its foundations, repaint it in even livelier colors, raise the fence even higher and bolster the iron gates, add more wooden bars to its windows and hold a huge celebration for the reopening. My mother would always take me along and dress me nicely for the event. Every time, more police soldiers would be assigned to stand guard. And still, like clockwork, it would all happen again. Someone would throw a can of gasoline and a single lit match. That was all it ever took to create mayhem and misery. After the most recent fire, nobody had bothered to the renovate the church in an attempt to end the cycle of heartbreak. Or perhaps everyone finally grew tired of that frivolous game. The church remained open for prayers, and the outside walls retained their black coat of hatred. It smelled of burnt wood and reeked of fear. The entire building was left in this state, hard on the eye and the heart and intentionally so, spitting guilt and shame onto those passing by and cautioning those who dared to step inside against the inevitable. The scene forced me to pull at my mother’s hand and ask the obvious question again: “Mama, where are we going?”

Impatiently, she said, “I don’t know, are you happy now? Just walk silently!” She usually did not like to talk much—or, rather, she did not know how to. Her answers were always simple and direct. Sometimes she’d speak only to divert questions away from her, always terrified of what thinking might lead to. She looked confused for a moment, as if my question had reminded her that our journey had no destination. And that this reality was not a choice, but a necessity. The necessity to do something with no desired or even foreseeable results. She had no option but to keep walking, for as long and as far as possible, hoping for something to happen, for some kind of deliverance … for an end.

“Mama, aren’t they going to fix the church?”

“No, this is better; nobody will want to burn something that’s already burnt.”

This was not a very convincing answer, but I was relieved by it. I had succeeded in tricking her out of her silence and distracting her from unanswerable questions. I trapped her in a conversation and brought her out to the shore of her loneliness. That was the moment she decided to reach out and ask for help. She stopped for a moment and looked around her, then back towards the church after we had passed its gate. She pulled me towards the gate. The closer we got, the more anxious I became, an all-too-familiar feeling that always hit whenever we passed by or entered a church.

Two thin soldiers sat by either side of the gate. It was one of those rolling gates with squeaking gears that you can hear even without them moving. One of the soldiers was asleep on a plastic stool, his jaw dropped open. The other one was standing on the opposite side with a hollowed face, leaning his rifle onto the wall next to him, its barrel pointing upwards. We had to pass between them on our way into the church, as usual. I used this opportunity to look through the barrel, which leaned in my direction. The sight of guns in front of a church and around it gave me a rush of curiosity tainted by the usual anxiety. I raised myself on the tips of my toes to have a clear view; there was nothing inside but dread. A familiar tightening of the chest imposed by the darkness inside, concealing the possibility of a random bullet breaking loose and penetrating my face.

I tripped on the door frame as my mother dragged me inside. But her grip on my hand was tight; I lost my balance for a moment and hung there, with no ground under my feet. For a moment, I was overwhelmed by uncensored, unfamiliar peace.

“Look ahead; walk properly!”

The smell of burnt wood filled the courtyard. The roof opened onto the sky, and a layer of black soot covered the walls. The floor was laid with new, clean, and smooth sand, disfigured only by fine ash lining the church walls.

Mama crossed the yard towards the nave with careful steps, and I followed her with the same caution as I counted my steps from one point to another. Sixteen steps from the gate to the church door. She stepped with one foot into the empty nave. There was something striking and alluring about the spectacle of a burnt church, a humility that enveloped ruin, a streak of beauty that unfolded quietly from below the destruction, emerging only because of it and always in spite of it.

Mama hastily cast the sign of the cross while facing the altar. I stood before the icon of the Virgin and Child, the body of baby Jesus naked, chunky, and flabby. It was one of those icons in which children have distorted features, making them appear like adults, disfigured by malicious smiles. Mama muttered a few words, from which I could only make out O Mother of Light, o Queen as she raised her hands up, pleading. The Virgin’s gaze was one of indifferent resignation. Mama took hesitant backward steps out of the nave and sighed in relief, as though she had carried out a heavy duty.

Her steps regained confidence once more, as she turned to the only room in the yard left untouched by the fire. Everything else was completely burnt, at least from the outside. A canteen selling vegan snacks for Lent and soft drinks, a library of icons, spiritual books, and hymn tapes, a little kiosk for the church-cleaner who had a slight limp — all had been lost in the last fire. As we approached, it turned out that it was not really a room, but rather a makeshift booth, hastily built after the most recent fire. It was made of nailed particleboard planted into the sandy ground, and above the boards a layer of tarpaulin for protection against the elements.

Mama knocked on the booth’s open door and walked in without waiting for a response. Inside was a young, skinny priest with a barren chin and a slightly worn-out black cloak, which gave his appearance very little warmth and solemnity. The man seemed half-asleep. He was resting on a wooden chair surrounded by heaps of cardboard boxes. His eyes slowly opened and it became immediately evident that his sight was very poor. He stared at us for some time, then smiled and apologized for the chaos. He asked my mother about the purpose of her visit. He seemed rather perplexed by our presence. Before answering, she gently nudged me towards the door.

“Wait outside, my dear. I need to have a grown-up conversation with Father.”

I bowed obediently and exited the booth. I did not go too far, but sat on the ground a few inches away and started to play in the sand. I removed some, making little holes that revealed the layers of ashes below and then refilling them. I imagined I was concealing the traces of a crime that had been deemed a cold case, which everyone was trying to forget. I was able, without much trouble, to hear my mother’s conversation with the priest. There was nothing I did not already know. I was as much a partner as a witness. I was always bothered by the grown-ups’ insistence on treating children as though they were blind to what happened around them, deaf to groans, slaps on faces, and murmurs of fear. What confused me even more was that they rarely made a real effort to hide any of these terrible things from us to begin with, yet still pretended like nothing happened.

I had witnessed everything, and was elated when Mama started stuffing clothes into the black garbage bag; we did not own suitcases back then. Earlier, Amo Raga’i, Tante Hilana, and I had heard five bangs coming from the kitchen — all of us witnesses to my father crashing Mama’s head into the wall. Seconds later, she came out, and he followed. She was neither sad nor angry; the right half of her forehead was swollen and red.

She hurried in, her voice ringing with guilt as she apologized to Tante Hilana. “I swear … I swear, it didn’t even cross my mind … please forgive me!” She rushed to pick up the food that she had earlier laid out for Tante Hilana, and carried the dishes with her trembling hands back into the kitchen. Shortly afterwards she came back into the dining room with the non-fasting food, and laid it in front of the guest. Tante Hilana was perplexed. She looked around with raised eyebrows and a mouth wide open, begging for an explanation.

Suddenly, she understood, and instantly collapsed into tears, struck by the realization that it was all because of her. “Damn you, Maurice! Why would you do this? Am I not suffering enough? Do I not have enough grief!”

Amo Raga’i embraced her gently. He begged her to calm down, for the sake of her health. Sadness was bad for her, as was fried food, among many other things. We all knew that very well; how could Mama forget! A few months earlier, the doctors had discovered that Tante Hilana had the bad disease; it had spread from her breasts to all her other organs. Everyone knew that her health was deteriorating, and quickly at that. She did not have much time left.

Mama rushed towards the half-dead woman and took her in her arms. She held her tightly and tried to calm her down as she fought her own tears, so as not to make her guest feel even worse. Her consolation only agitated Tante Hilana further, and she started hitting at her own chest.

“Oh my darling, how can you be the one consoling me!”

Tante Hilana refused to touch the food, despite all her husband’s and my mother’s pleading. Eventually, she agreed to go up to the bedroom and rest. My mother supported her up the stairs, twelve steps from the ground floor to the upper floor; she climbed them leaning on my mother’s chest. I counted behind them. She stopped on the ninth to catch her breath, held my mother tight, and kissed her head, then went up the three remaining steps, her panting getting louder every moment.

I was with them in the darkened bedroom. Tante Hilana lay on the couch without changing her clothes. She stared at the ceiling with eyes wide open, and told my mother to leave. She told her to not put up with this any longer. It was this exact misery that had made her sick, misery poisoned her body, clawed its way through her organs, one by one. First her liver, then her uterus, and finally the blood cells. And now it was too late. The cancer had invaded her entire body. All Amo Raga’i’s attempts to make amends for the misery he had caused her were now pointless.

“Save yourself, Um Sherif, don’t repeat my mistake!”

I heard Mama repeat Tante Hilana’s sentence to the priest over and over. I was elated that we had left the house, grateful for the sick guest and her advice and persistence. This was the first time my mother had done it of her own accord. He would usually be the one to kick us out after every fight. Sometimes he would do it without any warning or trigger. After a long, eventless day, he would wait till nightfall, pull us out of our beds, and throw us out. He did this very sternly and calmly, without any anger or resentment, as if he was just playing a pre-scripted part, as if it was all out of his hands, as if he was simply carrying out blind justice.

I was truly ecstatic that we had left. Nothing is harsher than living under constant threat. We lived in perennial fear that he would throw us out on the streets in the middle of the night “like dogs,” as he put it. Nothing wounds the heart deeper than not feeling safe in your own house. Your bed becomes made of fear, and being locked in your house is now a source of terror. The walls that shield you from strangers turn into thick clouds of endless anxiety and anticipation. The hand that is meant to comfort you instead snatches you out of your sleep and throws you into waking nightmares and their monsters.

“What can we do for you now, child?”

The priest’s voice was a bit shaken with confusion … or, rather, impotence. My mother did not have an answer. Her story was yet to have an ending; she was not even sure what ending she hoped for. She knew how easy it was to speak about sadness. She knew many sad stories by heart — as I was sure the priest did as well, by virtue of his work.

She also knew how difficult it was for one to tell stories of happiness. She did not have much to say about those and they did not concern her much. All she aimed for was to give the priest a fair idea about how complicated her own story was and how trivial misery can be.

This was not her first time asking for help. She was very aware of what the Holy Book says: That is why a man leaves his father and mother and is united to his wife, and they become one flesh. How could flesh abandon its own? How could she sever the head and separate it from the remaining organs? For the man is the head of the woman as Jesus is the head of the Church. That is what the Holy Book says. And what God brings together, man cannot separate. She knew what the priest was going to say; she knew what everyone was going to say. This was her struggle. It was her cross, which she had to carry patiently. The priest was going to remind her of the Virgin’s example — she was sentenced to the sword, but persevered.

And she was going to respond: “But, Father, I’m not the Virgin.”