Is the new exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art “evidence of women helping to redefine and empower women everywhere?” As LACMA notes, it features “works by women artists who were born or live in what can broadly be termed Islamic societies. Frequently perceived as voiceless and invisible, they are neither.” Through Sept. 24, 2023.

Philip Grant

Women Defining Women in Contemporary Art of the Middle East and Beyond is a vast exhibition at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art that runs until Sept. 24th. It presents visitors with the opportunity to view 75 works in a variety of media by 42 women artists. These mostly living artists have various connections to countries from Malaysia to Senegal by way of Iran and Palestine.

That I focus here on a handful of works should not be taken to mean that the others are not of interest, but it should be seen as an indication that exhibitions of this size are too overwhelming unless one has the opportunity to attend several viewings. An artwork should act on us slowly, seep into us, stir us and provoke us, draw us in to an interactive spiral from which we emerge transformed in due time, no longer exactly the person we were when we entered into dialogue with it. In exhibitions this extensive it is difficult, if not impossible, for the agency of the work of art to unfold. Instead, an experience, so familiar from contemporary urban living in so many places, is staged once again: rushing from piece to piece, we can only feel that we have seen something, something big, something from which we might after the fact extract some shards of meaning.

Perversely then, no doubt, I spent a good while watching, and straining to listen to, Zineb Sedira’s 2003 video Retelling Histories My Mother Told Me… in which the artist interviews her mother about her memories of the French occupation of Algeria. Unlike Palestinian-Lebanese-British artist Mona Hatoum’s moving 1988 Measures of Distance where the artist’s voice is supposed to be somewhat indistinct as she reads her mother’s letters from Beirut to her in London, which conjures up the enforced separation caused by the Lebanese Civil War (and behind that, the family’s separation from Palestine during the Nakba), we should be able to hear the exchange between Sedira and her mother. Of course, the English subtitles tell us much: the violence of French occupying soldiers and their Algerian collaborators (the harkis); the particular direction of that violence against Algerian women; the racialized as well as gendered quality of that violence — “Did they want to take you because your skin was paler?” the daughter asks, although the French soldiers did not in the end rape her mother. Yet only by actually listening do we realize that the daughter speaks French almost exclusively. Sedira was born and raised in France, before moving to London, whereas her mother replies in Algerian darija, a sonic and linguistic instance of the complex and contradictory marks left by colonialism.

Retelling Histories, My Mother Told Me… might easily be read as feminist life history or sociology, rather than an artwork, were it presented in a different setting. A number of the artworks in the LACMA exhibition might similarly be placed on either side of the porous boundary between the two, or better still be regarded as further indicators that the boundary has been undergoing a long, steady dissolution. Hengameh Golestan’s two photographs from her Witness series, of women demonstrators in Tehran participating in what is today a celebrated protest against the new revolutionary government’s first attempt to introduce a compulsory hijab law, are both documentary in quality and eloquent invocations. They reveal some women’s determination at the time to inject a feminist consciousness into the newly victorious revolutionary movement — an effort marginalized and suppressed in 1979. These protests would become increasingly resonant in Iran in later decades, from the 2006-08 One Million Signatures Campaign to End Discriminatory Laws and the “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprising of fall 2022.

On the other hand, two portraits of young women by the late Shirin Aliabadi, “Miss Hybrid nos. 3 and 6,” are as luridly colorful and individual as Golestan’s intense black & white images of demonstrators on a snowy late winter’s day are somber depictions of a spirit forged through collective struggle. They also share a certain defiance, whether against a newly announced law declaring a reconfigured patriarchal regulation of women’s public appearance as in the case of Golestan, or more subversively within that regulatory regime three decades later in Aliabadi’s, with women too young to remember the revolution in bright, tight clothing and headscarves, revealing a good half of their bleached-blonde locks — transgressive subversion of mandatory hijab rather than open opposition to it. The “Miss Hybrid” of the title seems to be a nod to the combination of (presumably wealthy) Tehran neighborhood or locale and a creative adaptation of Western fashion — or more thoroughgoing bodily modification in no. 3, with her bright blue-tinted contact lenses and the narrow bandage on the bridge of her nose, a mark of recent plastic surgery to make its size and shape more “European.”

Yet is there not something more critical here, hinted at by the possibly belittling “Miss” as well as by the sheer gaudiness and self-absorption of the images? Set against the nativist and repressive patriarchal regulation of women by state apparatuses, how far can subversion go when founded on adopting materials and brands that make sense primarily through how they produce a still-patriarchal Western consumerism? We are confronted by the paradoxes of individualism: as individuals produce themselves as individuals through consumerist practices, they come to resemble millions of others — and yet it is precisely because of this resemblance that individualism becomes political at all.

Feminist movements don’t just make statements about women, or even exclusively from the positionality of being women. They make statements about gender, and therefore necessarily about men, and sometimes other genders. There is a double bind at work, as struggling against the economy of patriarchal violence risks reproducing it. If we take seriously the curatorial suggestion that what joins these works is “women defining women,” under what conditions do they do that — and indeed, how did the artists already come to be defined, and define themselves, as women? These are not questions the artworks themselves can answer, but they do give us pointers.

Take the question of violence. In her photograph “Homeland Guard,” Kazakhstan-born artist Almagul Menlibayeva shows a topless young woman in camouflage pants and soldier’s hat, a fox skin perched on top of it, holding another military hat over her breasts. Palestinian artist Laila Shawa (1940–2022) in “Disposable Bodies 5 (Shahrazad),” offers a gold-painted female mannequin torso studded with brightly colored stones, an ammunition belt wound round its shoulders and waist. In “Feud,” Kezban Arca Batibeki presents us with two strikingly stylized mixed-media — acrylic, sequins, beads, and embroidery — images of women facing one another, their thick black hair exploding upwards or flaming forwards, connected to one another through their confrontational postures and the identical handguns pointing at each other, the tip of that held by the woman on the right straying into the pictorial space of the woman on the left.

“Disposable Bodies 5,” plastic, rhinestones, Swarovski crystals, peacock feathers and wire, height 88 cm., 2012 (courtesy LACMA).

All three pieces draw on and mockingly re-stage quintessentially male violence for their arresting imagery, and therefore for their affective force. Are women compelled by the enduring structures of this violence to assert themselves through it, to replicate it, and in so doing to risk turning it on each other? Such would seem to be the sense of “Feud.” Is there a danger that women are doomed to replicate a stereotyped role as objects of male sexual desire even as they subvert militarized hypermasculinity — in the case of “Homeland Guard” and “Disposable Bodies 4 (Shahrazad)”? Is the parodic re-enactment of this violence sufficient to undo the effects of the real thing? How far can irony and subversion take us in undoing the age-old economy of masculine violence? The beauty of these works is that they both sap the legitimacy of this violence by parodying it, and pose these awkward questions about the limits of their own effectiveness. “Homeland Guard,” with its mockery of how this militarized masculinity also creates itself through the killing of “trophy” animals, makes us wonder too whether the reconfiguration of gender relations must not necessarily also bring about the reconfiguration of human relations with other species in order for it to be meaningful. A predicament foundational to feminist critique and struggle is performed through these three pieces: There is no way to simply step outside gender-based forms of domination — they are constitutive of all our worlds — and yet it is imperative to find a way, eventually, to move beyond them and create new forms of gender, new ways of relating.

One of the great virtues of the exhibition is the way it undoes its own (apparent) premises. Firstly, that of women defining women. When I first began learning Persian, educating myself about all things Iranian, and visiting the country, in 2004-6, I was struck by Western media’s cultivation of dichotomous images of Iranian women: either severe, their black chadors wrapped tight about them, or resembling Aliabadi’s young models, their exact contemporaries, usually depicted at some “underground” party as evidence that the “youth” were defying the “mullahs,” a defiance legible for Western observers in women’s bodies and dress. This cliché of representation has long since spread to certain neighboring countries: witness the BBC offering us, as shot by Magnum photographer Olivia Arthur, its leading image of young women in sleeveless tops dancing. Are the “women of the Middle East” “frequently perceived as voiceless and invisible,” as one official summary of the exhibition would have it? Or are they not constantly being made visible, whether as oppressed victims possibly deserving Western rescue (white men and women saving brown women from brown men, to adapt Gayatri Spivak’s celebrated phrase), or a partying in defiance of largely male state or religious authorities in their desire to be “just like us”?

As for voice: who, or which institutions, is it that have the authority both to declare this invisibility, and to take it upon themselves to show “us” (in the putative “West”) that Middle Eastern women do indeed have voice? No exhibition of Middle Eastern women defining women can take place before others have decided what kind of artist and what kind of artwork might best stand for Middle Eastern women in Los Angeles, California. It is never purely a case of those women defining themselves as women. The “Western” museum cuts and frames, defines them as doing the defining. (The curator of the LACMA exhibition is Linda Komaroff, a white Islamic art specialist with a PhD from NYU. ED.)

In this context, it is striking to see one of Tahmineh Monzavi’s black & white photographs of Tina, sitting in a metro carriage in Tehran. She sits opposite at us but refusing to look at us, with a physique and especially a chin that most of us are used to seeing as masculine, but in feminine attire (as defined by the Islamic Republic) — a trans woman Monzavi photographed over several years before she passed away in 2020. Other images in the series (not included in the exhibition but on the photographer’s website) raise troubling questions about the subjecting effects of the photographic gaze, but Tina, here, has a quiet dignity that is enough on its own to unsettle the naturalism of the category “women” — and therefore of “men,” too — to remind us that gender requires constant stabilization, and that in different ways in different places new formations of gender have long been emerging that defy institutional attempts to fix them.[1] As art historian Jeannine Tsang puts it, in her talk “Why Have There Been No Great Transgender Artists?” which references a now classic piece of feminist art criticism, Linda Nochlin’s 1971 essay, “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”:

In our feminism, might we also consider when gender binaries don’t service identifications of artists as genderqueer or trans, and reflect on how we deploy and narrate genres of exhibition, monographic study, or collective organizing, such as the all-woman exhibition, the woman-only monograph, or the separatist community event? As we take up these genres today, I hope we calibrate how their use might afford recognition while also amplifying the existing isolation of artists identifying within a transfeminine field.

The second way in which the exhibition neatly undoes its own premises is in titling itself “the Middle East and Beyond,” which allows the inclusion of artists from, or at least originating from, or located in Pakistan, Malaysia, Senegal, Kazakhstan and Nigeria. Certain definitions of the Middle East would exclude Afghanistan and Turkey as well, not to mention Morocco and Algeria. The latter would of course be included in the nowadays widely used compound term “Middle East and North Africa,” but even more than the “Middle East” (whose East?), this is a term whose colonial origins are hardly hidden. The rest of Africa, “sub-Saharan Africa” (geographically erroneous), (an often unspoken) “Black Africa” is rendered wholly other, as if by its very blackness (and therefore the implied non-blackness, sometimes even whiteness or near-whiteness of “MENA”), the rest of Africa must be treated separately, and is fundamentally different. Including Nigeria, Pakistan, Malaysia, Kazakhstan under the rubric of “beyond” suggests we might try to — must — finally dismantle these colonial categories and their ethno-racial logics. Perhaps, there has to be a Middle Eastern exhibition at the LACMA because there is a Middle Eastern department, and other departments deal with other geographical areas, and institutions are potent motors of inertia. However, if there must be, then let it at least hint at the dangerous absurdity of these dividing lines.

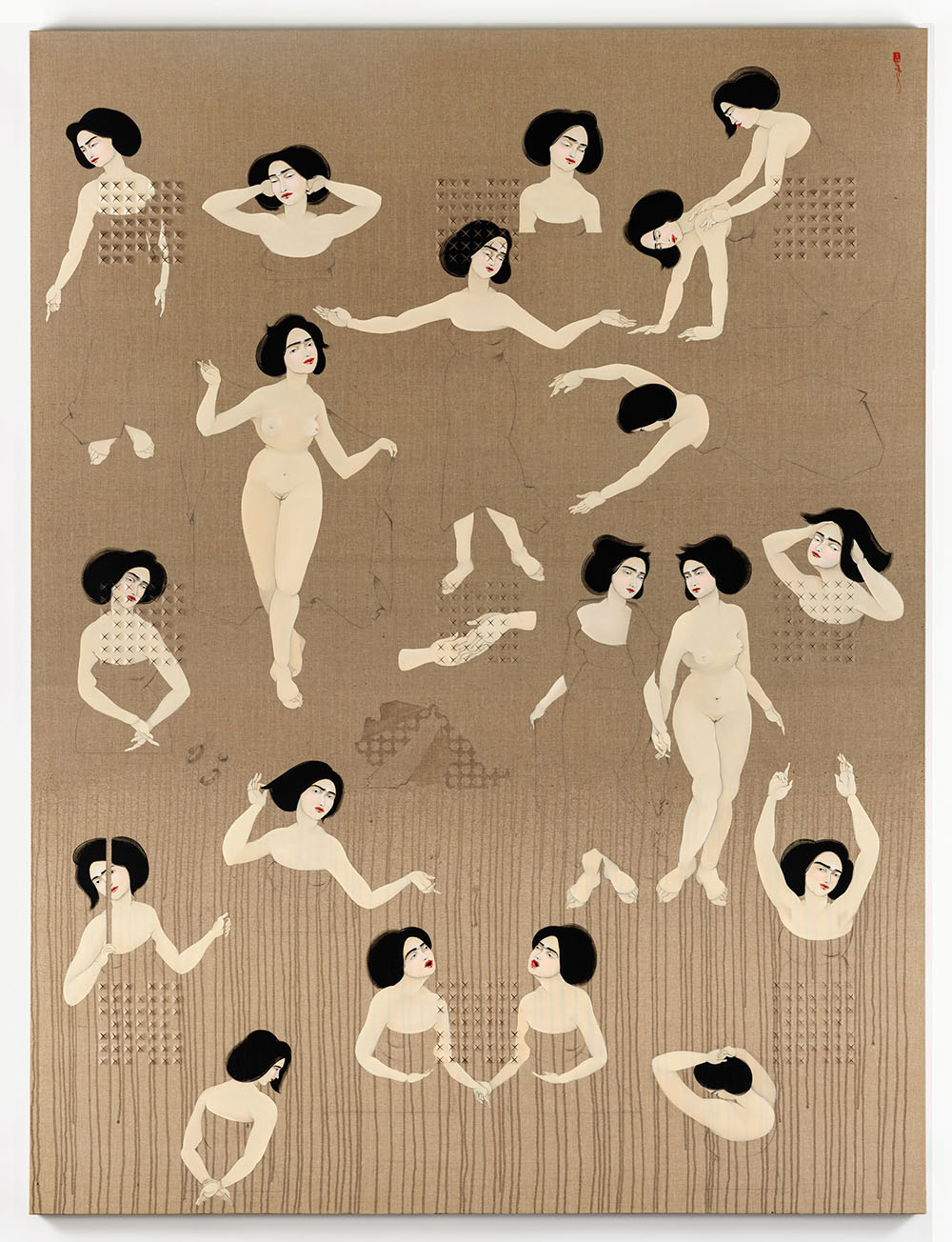

In any case, however defined, very few of these artists are simply Middle Eastern. Many of them emigrated at quite a young age to Europe or the United States, or even if they left as older adults, have been resident there for a long time. Some of them were born and grew up in Europe or the US. Despite the deliberate development of sizeable market ecosystems for contemporary art in the region (Sharjah etc.), European and North American galleries, collectors, museums, their funders and donors continue to have tremendous reach and attractive power, as do their art schools where a number of the artists represented here trained. Moreover, if we take, for example, Azade Köker’s “Deconstruction (Venus)” or Lalla Essaydi’s “Odalisque and Harem#2,” which engage self-consciously and with considerable aplomb with longstanding tropes of European art, and in particular with its objectification of women or of the female form, whether Roman deities or “Oriental” beauties, we will recall that these artists operate within (and yes, sometimes transgress upon and subvert) a West-centered visual and formal economy as much as within a political one.

This is hardly a secret, but reiterating it helps us comprehend a little better the huge range of reference dwelling within the terms “Middle East” and “Beyond.” “Middle East” has to encompass positionalities and working conditions as widely divergent as that of US-born and raised, Los Angeles-resident daughter of Yemeni immigrants Yasmine Nasser Diaz, represented here by a pink neon sign reading “Hannāʾ bint [daughter of] Ghamar,” which playfully questions traditional Arab patronymics — and Palestinian photographer, video and performance artist resident in Jerusalem, Raeda Saadeh, whose two-channel video of herself clad in black vacuuming on top of a hill in an arid landscape gestures at once to the tediousness of gendered domestic labor and to the long, drawn-out, sometimes apparently futile, but always necessary efforts of the Palestinian people to live in dignity and freedom, in the land that is their home. “Beyond” stretches the “Middle East” beyond breaking point: what ready-at-hand identity category is good enough for Maïmouna Guerresi, a white Italian feminist artist who converted from Catholicism to Islam in 1991 when she visited Senegal and ended up marrying a member of a Senegalese Sufi brotherhood?

Perhaps giant exhibitions make sense only in the context of the museum economy, especially in the United States. Here, public funding is scarce and museums are dependent on the largesse of rank upon rank of donors, the grandest of whom will see their names inscribed on walls or printed on the labels of artworks, or perhaps even bestowed on buildings, the humblest of which are the anonymous paying public.[2] Perhaps it is mainly, or only, institutional inertia (decades of funding congealed in all that infrastructure) that prolongs the life of mega-museums, when there are surely so many other settings in which art, especially contemporary art, can be better viewed, where artworks can actually act upon us as art, where the artistry of artists might be more fully appreciated.

Women Defining Women was surely not assembled with the intention of provoking this kind of diffraction,[3] but this is the effect of its sheer scale and of the impossibility of doing any kind of justice to more than a small selection of its works (I am particularly disappointed not to have been able to fit those of Hayv Kahrahman and Gazelle Samizay in this review). These artworks deserve more focused contemplation than is possible within so capacious a theme to be able to do their work properly. If we are to ask, then, what kind of function the large exhibition at the large museum might more usefully serve, the kind of historical approach with a focused theme the LACMA’s forthcoming exhibition, Dining with the Sultan, on the arts of feasting at medieval and early modern Islamic courts, seems to offer might be the answer.

Notes

[1] For a highly perceptive and subtle, and at times cautiously optimistic, account of being trans in modern Iran contemporary with Monzavi’s photographs of Tina, I recommend Iranian American feminist historian Afsaneh Najmabadi’s part-historical, part-ethnographic account in Professing Selves: Transsexuality and Same-Sex Desire in Contemporary Iran, Durham, NC: Duke, 2013.

[2] US$20 a visit (for the entirety of the museum’s collections, including this exhibition), or $25 if resident outside LA County, although visitors aged 17 and under can visit for free if they are county residents ($10 if not, unless 2 or under), and all county residents may visit for free after 3pm during the week (the museum is closed on Wednesdays).

[3] As opposed to the conventional reflection, feminist scholars of science Donna Haraway and Karen Barad have developed the idea of “diffraction” as an optical metaphor for the kind of intervention that seeks to make a difference in the world rather than just holding up a mirror to it.