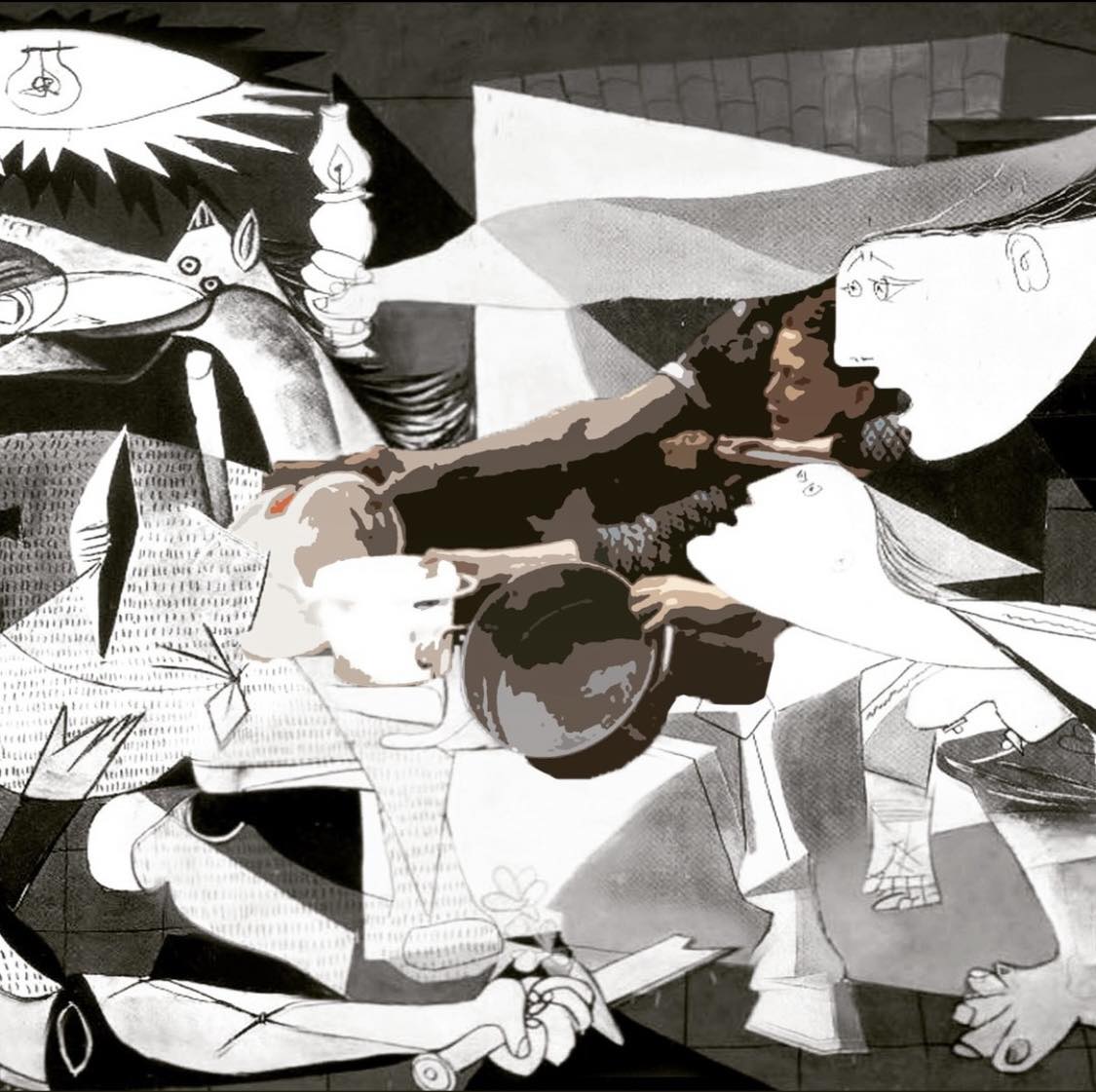

A few entries on a genocidal map…A walk in the Valley of Death that is the war on Gaza and the reckoning to come.

Faris Lounis

Translated from French by Jordan Elgrably

The Map of a Genocide Victim

بيانات على تذكرة التطهير

Our correspondent at the Tomb of Humanity reported the following:

Animal flour famine on the throne

Mixed with sand, the sea’s blackened water

Humanitarian aid? A crime, for peace activists

Block ports and passages

“May they croak,” they say, “all criminals, from the fetus to beings on the deathbed!”

Fingers hands legs amputated, why anesthesia?

“Let them taste delight in the gall of the atrocious, they say, let them quench their thirst!”

More bombs, let the living Truth undress!

Under the rubble of Nineveh I see

Skeletons and skulls still in black clothing

Their blood mutilated, the crows still watch!

In the air I breathed these words and walked through the still-smoldering ruins of a square of buildings entirely blown up, in accordance with respect for the rights of human animals and international law — depending on nationality and political allegiance, I heard a voice, a pile of meat, human shreds, next to a hundred soldiers celebrating a wedding, telling me:

“My letter written in my blood. It is my blood. It’s my blood. Here! It must go out to sea.” With trembling fingers, I took the letter and opened it. The horror seized me and I was stunned:

“I have no name. No history, no future. I await my certain death, which is in your hands, O messenger of the dead, under the bombs of civilization. I’ll be neither a corpse nor a statistic, for my body, this filthy heap of inglorious meat, this scandal of blood, in this world, is denied the right to a span of earth beneath the hell of man … Since the cement works dance to the rhythm of the bulldozers, what is the salvation of my body? This journey of bloody crumbs … This is my song, after which I can die happy!”

The rest of the letter showed the map of a genocide victim:

“Name: Hayy, Vivant, citizen of the world’s largest colonial internment camp.

First name: a refugee before I was born, expelled in 1948 from Jaffa, the land of orange trees and the azure gateway to Palestine.

Age: from river to sea, from Carmel to the sands of Sinai, since 1917, colonized and resistant.

Profession: spending my life in vain to prove that I’m a human being, aspiring to live as an equal on his land.

Skin: bleached black with the phosphorus of bombs that target only those who walk the path of freedom.

Size: pompously undressed, my flesh lacerated, with delight tortured, my limbs amputated. Of my dispossessed body, a half remains for cheap crime.

Hair: stained with the blood of a burned baby, its body smoking and charred from the ruins.

Eye color: white from the marble sweat of the atrocious spectacle.

Nose: blocked by CO2 emissions, ecological preaching obliges …

Mouth: thirsty, hungry, washed-out sewage.

Direction of birth: here lies inhumanity. The tomb of human rights on the left, the sarcophagus of international law on the right.

The profession: powerless spectator of the second Nakba. The purge is underway, the blockade our theater. What’s the use of my hand? Sewing up shredded babies. In the dream a funeral remains possible, in the midst of the horrors of the immense work of the civilized, in the name of their right to defend themselves.

Accusation: living and refusing to leave the Land of Christ. I eat sand from sewers and debris from 250 kg bombs.

Reasons: doesn’t want to die or camp out for another century, outside Palestine, in UNRWA barracks.

Verdict: the sea ahead, the barbed-wire mountain behind you, Sinai on your left flank … voluntary migration or a total hecatomb that would be named 360 km2.

After sending this map from a genocide victim to the editorial staff of my newspaper, Les Libertés indicibles, my boss, after his usual careful, critical and impartial reading, replied: “This tells a truth that we have all known for almost a century. But we can neither admit it, nor meditate on it with our eyes, nor believe in the veracity of the massacres committed in its name, for we judge that the words of this map and its letters of blood that lash our cowardice and our failures are incompatible with our affective determination towards the massacres in the name of the right to historical continuity of the colonial process that we, the free world, initiated in Mandatory Palestine back in 1917. In the name of the occupiers’ humanitarian right to self-defense, we can only politically and media-support this ongoing genocide by democratically refusing to publish the document you suggest. After all, it’s only Arabs who are dying… In case of doubt, it’s our lesson from past centuries that teaches it, evoking as in the first beginning the Pavlovian chorus of the sacredness of freedom of expression: “They don’t exist, so we don’t murder them. They die on their own, divine grace relieving and crushing the necessary suffering. These Bedouin invaders are squatters on their own land. God’s earth is big, and the Arabs’ Sahara even bigger. Let them be parked on an artificial island in the middle of this sea of sand, and may Ben Gurion’s work come to an end. There is a time to live, a time to be expelled and a time to be murdered, if you cling to life as to the olive branches and its clay.‘”

As I took to the atrocious paths strewn with corpses, I lightened my bare steps in deference to the constellations of unburied remains. Next to a torn, blood-stained tent standing in the middle of a muddy tide, I heard a three-year-old child, her right eye cut out and her left arm amputated, singing:

I want to be warm / I want to be warm / the cold comes to us from every side / from every side it comes to us / life is freezing without mommy and grandma / without mommy and grandma, life is bitter!

As I made my way back to Rafah, helpless in the face of this scandal, I thought of suicide. But I told myself, as I set about preparing my makeshift tent, that it wouldn’t be long before an American bomb would drench the petrified sands of the Tomb that Gaza had become with my blood. Every second of our lives was a reprieve, me and the civilians who shared my daily life, unwilling candidates for genocide.

I was on my knees just as I finished putting up my canvas with holes in it. Suddenly, I heard the deafening crash of a missile a hundred yards from our camp. Of the two-story house that had been targeted, all that remained was the first-floor wall, the frame of its orphaned window and pieces of dislocated scrap metal. As the huge wave of ash and dust dissipated, the mutilated and shockingly shredded body of a woman revealed itself to my gaze, already drenched in the murderous scent of death and cowardice. Her lifeless right arm clinging to the scrap metal frame of the disfigured window, her body hanging against the wall illuminated by makeshift spotlights, gave the impression of no longer wanting to return to the ground and its violated land. As I approached the corpse, I realized that it was Rima Hanna, a journalist friend who, alas, hardly escaped this umpteenth assassination attempt.

Blood flowed like a raging river from the pieces of flesh that remained on both legs, and on the wall I thought I saw:

Blood is its river

A tattoo seems to float

On the remains of the burnt camp

This faceless writing

On the sands of Gaza

Lie in the atoms of oblivion

The end of Humanity

Without beginning

And the body of Truth

O wandering shreds

Forever without a grave …

Vaster is the shadow of the olive tree

Than the oceans of refuge

More daring is the palm house

than the civilized rain of fire

On our shredded bodies

The rubble, oh infamous tomb

Here we’ll drink from the source

From our blunt stones

Here we will pour out our thirst for blood

Palm and orange trees

On this earth we lived

On this earth we will live

On this earth we die

Even in private chains

Shroud and prayer.