What are we to do with expressions of melancholy, political depression, or despair at a moment when there are so many reasons to feel the unspeakable and so much need to take action? Where does melancholy intersect, if at all, with the rage we might consider more appropriate for an issue entitled BURN IT ALL DOWN? What acts does melancholy foreclose? And which does it engender?

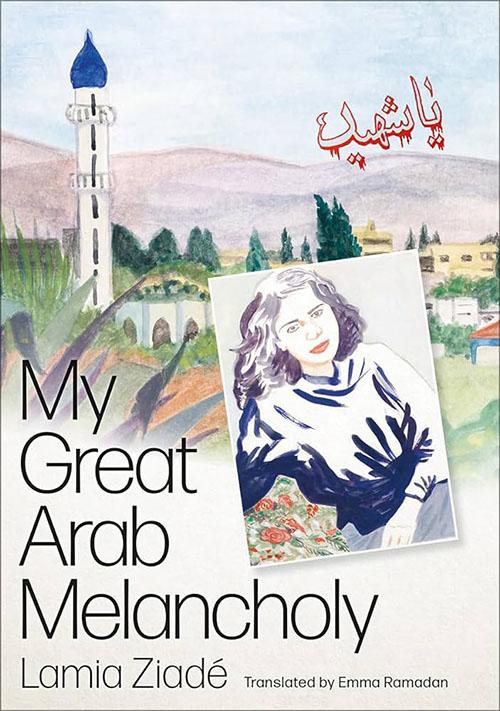

My Great Arab Melancholy by Lamia Ziadé

Pluto Press, 2023

ISBN 9780745348155

Katie Logan

The Lebanese author Lamia Ziadé uses the word “melancholy” to describe two of the many figures who populate her similarly titled My Great Arab Melancholy. The first is the young King Faisal of Iraq, deposed and assassinated at 23 years of age, whom Ziadé refers to as a “charming child, asthmatic and melancholic,” and later, a “melancholic teenager.” The second is the Shia Imam Musa al-Sadr, whose 1978 disappearance in Libya figures in Ziadé’s telling as one of the great tragedies of modern Lebanese political history. “His face,” she writes, “marked by great kindness, betrayed a certain melancholy.”

These figures, along with the cemeteries, mausoleums, and museums Ziadé visits throughout the illustrated volume, prompt a reckoning with the concept of melancholy. After all, what Malu Halasa calls the book’s “evocative title” is one of the many reasons she listed it among her most anticipated books of 2024 in this publication.

What characteristics does Ziadé read into the “melancholic” dispositions of two key figures, who seem to share very little but their presence in an expansive, ever-shifting version of Arab historical narrative? Does melancholy indicate a particular orientation toward the past or present? And this line of questioning leads me to consider the weight that single word asks the text as a whole to carry: What are we to do with expressions of melancholy, political depression, or despair at a moment when there are so many reasons to feel the unspeakable and so much need to take action? Where does melancholy intersect, if at all, with the rage we might consider more appropriate for an issue entitled BURN IT ALL DOWN? What acts does melancholy foreclose? And which does it engender?

These are urgent questions that have only become more so since My Great Arab Melancholy’s initial French publication in October of 2017. The trajectory into English itself has a tinge of melancholy as timelines are unsettled and forces of the market made clear. It’s a familiar story of awards circuits enabling translation — the text received a 2022 PEN Translates Award, and translator Emma Ramadan successfully applied for an NEA Translation Fellowship to work with both My Great Arab Melancholy and Ziadé’s more recent My Port of Beirut (2021). And while My Great Arab Melancholy is the earlier text, My Port of Beirut preceded it into English, suggesting a murky timeline in which the devastating explosion of August 4, 2020, is absent and yet haunting the English translation of Melancholy.

No matter the order, both texts showcase Ziadé’s preoccupation with sense-making through the acts of amassing and collaging. Her narrative approach is at once intensely personal — my port, my melancholy — and yet collective, as her illustrations expand to include the histories and archives of people across the city, country, and region.

Writing for ImageTexT prior to the work’s English translation, Carla Calargé and Alexandra Gueydan-Turek eschew the term “graphic novel” in favor of an “illustrated book with a spatial infrastructure resembling the genre of the travelogue.” Elsewhere, they refer to the text as an “album.” These generic designations suggest a reading experience that consistently implicates the reader. Despite the “my” of the title, both the French and English versions of the text use a familiar “you” throughout; table of contents and indexed maps prepare readers to travel alongside Ziadé during this geographic and temporal journey.

A journey this book is, as Ziadé’s recollections drift from actual travels in South Lebanon, Beirut, and Egypt to historical events and memories from Algeria, Libya, Iraq, Palestine, and Jordan. The “album” designation rescues the text from maintaining a strict or linear itinerary. Albums’ logics are more associative than a travel narrative’s, and one is less likely to read than encounter an album. Whether a photo album or album of music, there’s a participatory obligation to activate the text by returning to it, revisiting favorite sections and discovering new material each time.

Approaching My Great Arab Melancholy as an album or archive prevents it from feeling unwieldy. Ziadé’s efforts to catalog an expansive archive of Arab history — including the assassinations and downfalls of key political leaders, as well as decolonizing resistance movements across the region — are designed to feel overwhelming. She impresses upon readers the impossibility of a starting point or single narrative arc to this history. Instead, she asks readers to register rhythms and patterns. By paying attention to a range of moments at which a different future was possible and then demolished, she performs the work of critical melancholy, which doesn’t just echo current conditions of grief, rage, or despair — it opens us up into something painful, fierce, and connective.

One way to understand the project Ziadé has taken on is by turning to the long history of melancholy in Arab thought, though she herself does not reference this scholarship. Moneera al-Ghadeer traces a version of humoral theory through the philosophical and medical inroads of Avicenna (Ibn Sina), just as Nouri Gana points to configurations of melancholy in Lebanese Marxist intellectual practice. Borrowing from Husayn Muruwwa’s 1982 distinction between “‘lethal sadness’ (al-huzn al-qatil, the sadness that paralyzes and immobilizes), and ‘militant sadness,’ (al-huzn al-muqatil, the sadness that fights back),” Gana also characterizes melancholy as having one of two qualities. The melancholic is “self-reflexively principled, persistent, and proactive” while the melancholite remains “uncritically reactionary, impulsive, and counterproductive.”

If mourning is the act of processing a loss and incorporating it into our sense of reality, melancholy is a refusal.

Gana’s work helps readers understand Ziadé’s critical approach to melancholy—and to see its potential. He concludes that “melancholy attachments to incomplete losses are very taxing psychically but affirmative politically insofar as they keep under close scrutiny the historical injustices of which these still unfolding losses are the product.”

After all, in a gross simplification of Freud’s work on the subject, if mourning is the act of processing a loss and incorporating it into our sense of reality, melancholy is a refusal. The complexity of a loss, the scope of the feeling, and the ongoingness of the event mean the loss cannot be accepted. It is pathological, to use Freud’s term, because it is a refusal to normalize.

Resisting acceptance, refusing normalization, is political work. It’s the reason Sara Ahmed refers to the “melancholic migrant” as the figure who is chastised for naming — and thus refusing to accept — racism. The melancholic migrant tells us: “Don’t get over what is not over. Just in case we need a reminder: the dominant way of telling the story of the British empire in Britain has been as a happy story. That dominant happy view of empire is enforced through citizenship, by which I mean, to become a citizen is to learn that positive view and to be required to repeat it.”

To be a melancholic migrant, a melancholic traveler, a melancholic narrator is to resist repetition of the dominant story. Instead of suturing together, Ziadé fends off closure. An attempt to move past melancholy, to sanitize or iron it out, risks either reinforcing the pre-existing narrative or creating a new one from a reactionary position. Those perils, as Lina Mounzer has explained in this publication, include justification of unspeakable acts: “If the recent history of Western warfare has taught us anything it is that if your anger is righteous enough, then any violence born of that anger is righteous, too. Thus you may engage in mass slaughter and remain mostly blameless in the eyes of the world. Those that have been slaughtered are not people, after all, but human animals.”

As Ziadé demonstrates throughout this dense text, remaining with melancholy is a way of holding onto moments of potential. My Great Arab Melancholy is especially attentive to historical fulcra, those occasions just before the possibility for a more unified or liberated future is foiled. For Ziadé, these include the election of Ali, the Shia leader and Muhammad’s cousin and son-in-law, to the caliphate; the “exceptional and forgotten moment” of Gamal Abdel Nasser nationalizing the Suez Canal; and the period just following Bashir Gemayel’s election to the Lebanese presidency. Of these moments, she writes, “the reconciliation of believers seems possible then,” and “even the most skeptical allow themselves to dream.” Of course, each of these moments warps into failure with the assassinations of Ali and Gemayel, and Nasser’s 1967 defeat.

Ziadé doesn’t ignore the outcome of these stories but refuses to treat them as foregone conclusions. She seeks memorial practices that insist on the still unfolding nature of these losses. She lingers in places where the act of commemoration is lived and complex. Her travels begin in South Lebanon just after Ashura, the annual mourning of Husayn’s death. Observing the vestiges of the festival, Ziadé seems particularly drawn to the detail with which observers recreate the Battle of Karbala and the ways in which banners and visual markers change the region’s landscape.

Beginning with Ashura foregrounds the kind of collective, repetitive, and hyper-present mourning rituals that Ziadé gravitates to throughout the project. She visits “funereal and marvelous” cemeteries, where parents bring tea and picnics to sit with their lost children. She hears the story of Nada, a woman whose own losses and traumas mean that the only crafts she makes with the children in her care are funeral wreaths for the soon-to-be killed. She considers the legacy of Khiam Prison, the horrific detention center turned museum only to be destroyed by the Israeli Air Force in 2006 — the acts of reclaiming and remembering are that threatening. She holds up Emir Maurice Chehab as a kind of commemorative hero for having the foresight to protect the artifacts of the National Museum in 1975 by enclosing them in slabs of concrete. The unveiling of the artifacts, accompanied by the museum’s decision to retain echoes of the war through the sniper hole now punctuating the Mosaic of the Good Shepherd, speak to a tenacious, far-reaching version of commemoration.

Only a few moments of slippage disrupt the commemorative philosophy Ziadé develops carefully throughout the project. Standing in the Museum of Memories in Shatila Camp, she listens to a tour from museum owner Doctor Mohamed el Khatib. As the doctor presents artifacts, Ziadé’s response raises questions about her own project:

It looks like the back room of an antique store . . . you were expecting something more captivating. You are slightly disappointed. You thought you would find weapons of all kinds, Fatah or PLF posters, clandestine newspapers, photos of the fedayeen or of battles and massacres, flags, logos, keffiyehs, combat uniforms . . . but the doctor’s explanations deeply move you. These objects were brought by the camp residents or by their parents when they fled Palestine and were entrusted to him to preserve their memory. Objects with no historic, ethnic, aesthetic, or economic value, but which are all that remains for them of their country . . . The doctor makes you a coffee and comments on each piece. Almost none hold any interest apart from simply being there, in this camp. Only a few exude an aura of great tragedy.

It is a strange reflection that undercuts some of the cataloging Ziadé accomplishes elsewhere. My Great Arab Melancholy does indeed “exude an aura of great tragedy,” but it’s also attuned to a range of griefs more nuanced than this reaction suggests. If the cardinal sins of melancholy are erasure and forgetting — impulses that have removed Martyr’s Square from Beirut’s map and destroyed key landmarks of the Nasser presidency in Cairo — a determination to make visible is the melancholic’s guiding principle. In Nada’s classroom, the woman who teaches her students to make funeral wreaths also displays images of the dead and injured in Gaza. Ziadé transitions wordlessly to several full pages of these images. They are from 2014. They are from yesterday. Melancholy refuses to unsee the injustice. It asks us not just to burn it down but to hold on.