How the Trojans came to be associated with present-day Turks is a fascinating tale of discontinuity that is pertinent today. The story sheds light on the porous cultural borders between Europe and Asia, the fallacy of the clash of civilizations, the recent appearance of the West as a unified concept, and the cultural politics of its decline.

The West: A New History of an Old Idea by Naoíse Mac Sweeney

Penguin, 2024

ISBN 9780753558935

Arie Amaya-Akkermans

The Troy Museum in the village of Tevkifiye in northwestern Turkey, completed in 2018, brought together a vast array of artifacts from Turkish collections, related to the surrounding historical region of the Troad, close to the celebrated archaeological site of Troy. Most of the objects, however, have little to do with the setting of the Greek myth of the Trojan War, one of the foundational stories of Western culture, immortalized by Homer’s Iliad and Virgil’s Aeneid.

Troy is a real place, which has been undergoing excavation for the past 150 years. Yet antiquities said to have come from that legendary war from between the 13th and the 12th century BCE are from much later periods. As Naoíse Mac Sweeney writes in her new book, The West: A New History of an Old Idea: “Reality rarely gets in the way of a good story, especially when that story serves a political purpose.”

Whoever controls ancient Troy today, in the eyes of Turkey’s institutional archaeology, also controls the narrative of the clash of civilizations between Europe and Asia, one of the oldest ideas in the European tradition. The Turkish emphasis however, was an inversion of the traditional European idea. They didn’t proclaim a victorious West, personified by the Archean Greeks, but rather reclaimed for themselves the legacy of Trojans in history — one that has been claimed by many in the past. Modern archaeology has shown that Troy wasn’t simply a Hellenic city, but in fact had deep roots in Anatolian culture, a reality that has nurtured Turkish interest in the history of the ancient city. Even though “Anatolian” refers to the extinct Indo-European languages of the region and its speakers, today it is a blanket term for anything that can be identified as Turkish.

In popular consciousness, “Anatolian” also describes any kind of historical period, from the most remote prehistory to the present, if it took place within the borders of the modern Turkish republic, the present inhabitants of which are said to be the heirs to forty centuries of Turkish civilization. But the Ottomans had little affection for the term, which they found derogatory. It didn’t appear in Turkish republican archaeology or literature until the middle of the 1930s. The story of how the Trojans came to be associated with present-day Turks is a fascinating tale of discontinuity, which sheds light on the porous cultural borders between Europe and Asia, the fallacy of the clash of civilizations, the recent appearance of the West as a unified concept, and the cultural politics of its decline.

In her book Mac Sweeney explains that according to the seventh century Chronicle of Fredegar, the Turkic peoples of Central Asia were descended from Francio, a medieval name for Trojan warrior Astyanax, “who also happens to be the progenitor of the Franks.” How can the founder of the Merovingian dynasty and the forefather of Charlemagne also be an ancestor of the Turks?

The biography of the East/West binary is just about to get more nebulous. Mac Sweeney’s The West is not an account of the legacy of the Trojan War or an intellectual history of the West, but rather a portrait of fourteen men and women, from both East and West, spanning from the fifth century BCE to the present. Each in their own way articulate or challenge the political construction of the West as a concept that is neither fixed nor sempiternal, and has emerged as a result of multiple cultural exchanges across time.

Letters from the Ottomans

There is Francio in the chapter about the powerful Safiye Sultan, the mother of the late 16th century Ottoman Sultan Mehmed III. Safiye Sultan maintained a long epistolary relationship with English Queen Elizabeth I. Being a skilled diplomat, in her letters Safiye Sultan appealed to a shared Trojan heritage, an idea prevalent during the Tudor dynasty. To the English monarch, she had introduced herself as the consort of reigning Sultan Murad III, “the monarch of the lands, the exalter of the empire, the Khan of the seven climes at this auspicious time and the fortunate lord of the four corners of the earth, the emperor of the lands of Rome.”

There’s a famous tale about an Ottoman letter, dated a century before Safiye Sultan, which had the conqueror of Constantinople, Mehmed II, write to Pope Pius II to express his displeasure that the church did not support his 1453 conquest of the Byzantine imperial capital. Mehmed II reasoned that although Constantinople was a Christian city, both Turks and Italians had descended from the people of Troy. The letter is not fully recalled in The West and is apocryphal. It belongs to the “Sultansbriefe,” a group of letters pretended to have been written by a Sultan to Christian princes, the authenticity of which has long been questioned. Today they’re considered propaganda or entertainment from later centuries, but the letter sheds light on the importance of a Trojan pedigree in the historical imagination of the time.

How many peoples have actually descended from the Trojans? The list is long, but one should start with the foundation myth of Rome’s origins. The survivors of Troy fled their city, and led by Aeneas, they ended up in central Italy. It was Aeneas’ descendants, twins Romulus and Remus, who founded the city of Rome.

In The West, Mac Sweeney addresses the contrast between the myth and the present: “This myth might initially seem strange to modern ears. It may seem counterintuitive that the Romans, so often invoked today in the rhetoric of European genealogy in general and that of the European Union in particular, would claim an Asian rather than a European origin.” The master narrative is far less monolithic than that promoted by modern European institutions.

When the EU launched a 2014 operation to tighten immigration control and called it “Mos Maiorum” (Way of the Ancestors),” the reference to the traditions of ancient Rome irony might have been lost on them. Mac Sweeney captures the genesis of Rome beautifully:

It might seem equally counterintuitive that the Romans, with all their military might and imperial power, saw themselves as the descendants of refugees, the losing side in the most famous war of antiquity. The idea seemed particularly jarring over the last decade or so, as Italy struggles to cope with the influx of desperate refugees trying to reach its shores seeking safety, prosperity and a new life.

Yet the myth of Troy would go on to take many afterlives and become genealogies for many generations and not only for Western Europeans. Romans, Bactrians, the German Hohenstaufens, Byzantines, Renaissance Italians, and Ottomans all have claimed Trojan ancestry at one point or another, and those origin stories still shape to a certain degree the political present. Mac Sweeney argues that the West does not have a clear and simple origin in classical antiquity. And neither has the East, I would add. She makes a strong case against the clash of civilizations:

The Ottomans did not see themselves as fundamentally Asian, belonging to and representative of an East that was eternally and inevitably opposed to the West. Rather, they saw themselves at the head of a universal world empire, spanning three continents and embracing a myriad of peoples, languages and religions. They were just as much European as they were Asian, ruling from a capital city that straddled both continents.

But if this rich mosaic of genealogies, influences and origins is true, how did we end up with a fossilized idea of the West? The phrase “from NATO to Plato” imagines the West as an unbroken historical chain, from classical antiquity through the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, the Enlightenment and modernity, with the clash of civilizations between Europe and Islam as an added bonus? Mac Sweeney proposes a series of events that consolidated the progressive encroachment of the West as a unified whole, from the military victory of the Holy League against the Ottomans at Lepanto, to the coherent form that the Greek-Roman past took during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment. Finally it was the colonial adventure that amalgamated Europeans into a unified whole, in the presence of radical difference and shared profit.

The message here is that Western Civilization is a modern invention. “It is a version of Western history that is both factually incorrect and ideologically driven,” as Mac Sweeney writes in her introduction.

A Migrant’s Tale

Powerfully intriguing is the hypothesis defended by Mac Sweeney, among other classicists, that classical antiquity as Western heritage wasn’t reborn during the Renaissance, but actually born for the first time. The world of the ancient Greeks looked mostly eastwards, and the Roman Empire was a global enterprise; both regarded continental Europe as foreign and backward, and their relationship to one another wasn’t one of linear succession, but of overlap and superposition. For all its ancient pedigree, as Rebecca Futo Kennedy has pointed out, the term “Western civilization” proliferated only after the 1840s in the United States and Britain.

But the handmaiden of the modern West, the clash of civilizations, has a remarkably ancient past that returns to Turkey. The tale of Mac Sweeney’s first dramatis persona is perhaps the finest writing in The West:

A migrant stands on the beach. He looks out to sea, his mind as well as his gaze reaching out towards his homeland, a continent and a lifetime away. He took his first steps into exile years ago, sailing away from the rough coast of Turkey on an overcrowded boat. He had been running from the persecutions of a tyrant and the fury of a fundamentalist mob, hoping for a bright future in Europe’s most bustling and cosmopolitan city. But when he finally got to the great metropolis, his dreams quickly soured.

It is certainly the story of a migrant, but it’s not Aeneas, who received a warm welcome in Italy.

She continues:

Where he had once hoped for success, he encountered suspicion, and where he had once imagined opportunity, he found restriction. Later, when the government began to cultivate a hostile environment for migrants and instituted draconian new citizenship laws, he left. And so now here he stands — on another foreign beach, looking for a new start. Maybe this time, he will find what he is looking for.

It could be the life of a 21st century migrant, perhaps leaving Istanbul to reach Greece or Italy on a raft.

Actually it is the story of Herodotus, the ancient Greek historian, born to a mixed Greek and Anatolian family in fifth century BCE Halicarnassus, now Bodrum in Turkey. Conflicts with local politics turned him into a refugee in Athens, but then increasing xenophobia and consuming imperialism led him to emigrate once again.

The second time, he went to the small town of Thurii, in Calabria, near the Gulf of Taranto, where he wrote his magnum opus, the Histories. Last summer I spent time at the Archaeological Park of Sybaris, which comprises the successive ruins of the ancient cities of Sybaris, Thurii and Copia. Sybaris has never been excavated because of the underground water; Thurii was destroyed by Italic tribes long after Herodotus; and Copia was abandoned in the Middle Ages. But the landscape of the Crati plain still bears the imprint of migratory waves, between the mass depopulation of southern Italian towns from youth seeking a future elsewhere, the irregular arrival of migrants and the control of the ‘Ndrangheta, the Calabrian mafia. Herodotus would be displeased at Italy and Greece’s existing xenophobia, with the strong regional support for far right parties.

The West reminds us that the Histories is the earliest work of historical writing in the Western tradition. In the book Herodotus recounts the events between the years 499 and 470 BCE, when a coalition of small Greek city-states prevailed against the mighty Persian Empire, which gives it a place of honor in the imagined history of the West: “For many people, it has provided a founding charter for Western Civilization, offering an ancient precedent for the modern notion of the clash of civilizations.” But Mac Sweeney, a classical archaeology professor in Vienna, argues that this is a misconstruction of the text: “If we read Herodotus carefully, we find that he introduces the notion of a clash of civilizations only to undermine it.” As an Anatolian migrant, who experienced the toxic atmosphere of Athenian imperialism, he was suspicious of myths of purity.

About this period, she asks, “Should we be really surprised that someone like Herodotus, a bicultural migrant from Asia, no longer felt at home?” The Histories is an amalgamation of fact and fiction, the genealogies of different Greek cities, their diverse religions, beliefs and customs borrowed from many places, and the great deeds of other peoples in Herodotus’ world: Egyptians, Scynthians, Babylonians and Ethiopians. “Greek culture, Herodotus tells us, was anything but purely Greek,” concludes Mac Sweeney. The ancient historian points out that the division of the world into Europe and Asia was particularly ridiculous. The binary between East and West that the Athenian state pioneered in the fifth century BCE, and which Herodotus rejected, was but a political tool to justify the city’s dominance over other Greek states.

And it is precisely because it was a tool for Greek-on-Greek imperialism and propaganda rather than a historical experience, that there’s no real continuity between the age of Pericles and the European and American imperialism of the last three centuries. Mac Sweeney explains that the reason behind the Western claim that the clash of civilizations originated in Ancient Greece, is not that the West has passively inherited the conceptual model of Athens, but that the model “does the same conceptual work and fulfills the same political function in both instances —serving an expansionist, racist and patriarchal ideology.” Similarly, Troy was not a clash of civilizations, but “a conflict between closely related groups, bound together not only by shared culture and customs but also by intermarriage and family ties.”

Not quite East versus West.

Theodore I Laskaris

Another fascinating character in The West is the third Anatolian personality, this time in Byzantium, situated in history between Herodotus and Safiye Sultan. The Byzantine Emperor Theodore I Laskaris in the 13th century, born in Constantinople, but the first emperor of Nicaea, after the Fourth Crusade, had forced his father-in-law Emperor Alexios III to flee the imperial capital. This story gives us an insight into the world of the crusades, once again, not as a clash of civilizations between Muslims and Christians, but a series of complex, bloody power struggles, fought between different Christian groups, and sometimes between Christians and Muslims. Obscuring the role of Islam in the transmission of classical antiquity in the modern West is almost a necessary step in the clash of civilizations theory, but the frequent absence of the Byzantine Empire is an even stranger omission.

The Byzantines after all, were the heirs of the Roman Empire, and consequently, also of Troy, but they were also Greek speakers who had more or less direct access to the texts of antiquity and were as fundamental in its transmission to the Europe of the Renaissance, as Muslims had been a few centuries before. But the Byzantine Empire was certainly not in Europe: As the first historical figure to unify the Greek world under a single identity and political continuum, it is interesting that Laskaris did not locate Hellas (the Hellenic world) in Europe but in Asia. Mac Sweeney notes: “In a letter to diplomat Andronikos, he asks, ‘When are you going to come from Europe to Hellas? When might you glance again at Asia from the inside after passing through Thrace and crossing the Hellespont?’”

There are other remarkable characters in The West I have overlooked, such as enslaved African-American poet Phillis Wheatley, or Angolan queen Nzinga. My focus has been on the modern territory of Turkey, and the role this geography has played in the history of the idea of the West. It has not only been underestimated by Europeans who conceive of the Greek world as wholly Western; it has also been politically abused by Turkish authorities in attempts to falsify both the Ottoman past and the clash of civilizations as a source of nation-state building in times of crisis.

Crisis is precisely the key theme in The West. Mac Sweeney observes that the evidential basis for Western civilization has long crumbled, “and the overall narrative is no longer consistent with the facts as we know them.”

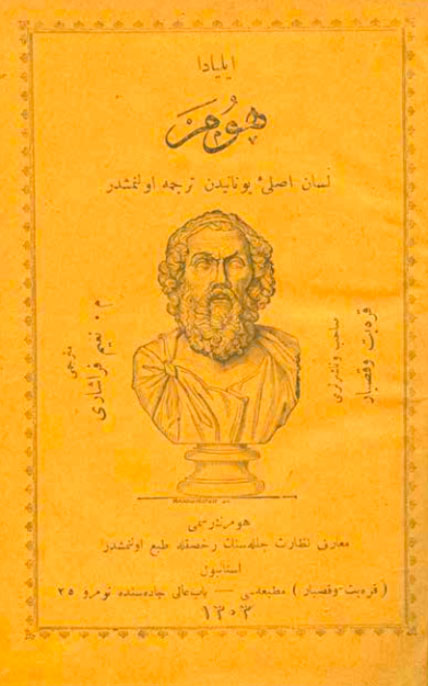

It is a narrative, which continues “long after its factual basis has been thoroughly disproven,” because it serves a political purpose. Since Mehmed II, the story of Troy has gone a long way in the Turkish imagination. It was refashioned at the end of the 19th century with the first Ottoman Turkish translation of the Iliad by Naim Frashëri, and the last Ottoman sultans saw in it the claim to their European past at a time of both reform and decline. In the republican era, it was Azra Erhat, the first woman translator of the epic, who used the story of the Trojans to erase the legitimacy of the Greek presence in Western Anatolia, at a time when Christian minorities were facing violent extinction in the region. Erhat’s ideas evolved into a cultural movement known as Mavi Anadolu (Blue Anatolia), which is today the official narrative of Turkey’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

In the widely read memoir of her travels through the Aegean with a group of poets and intellectuals of the young Turkish republic, Mavi Yolculuk (Blue Journey) published in 1962, Erhat writes: “Are you on the side of Troy, or on the side of the Greeks? Ten people shout in unison, ‘Troy’!” It was a great irony that Erhat’s translation of the Iliad was beautifully illustrated with black and white drawings by Greek Anatolian painter Ivi Stangali, who was forcefully deported from her homeland to Greece in 1964, as part of punitive measures against the Greeks of Turkey in the aftermath of political events in Cyprus

Could this innocent narrative of reclaiming the lands of Anatolia from Greeks by republican intellectuals, turned into sectarian and nationalist ideology, have emerged without the theory of the clash of civilizations? Herodotus would frown at this misuse of a story that he had himself disestablished. Turkey today is very far away from the narrative of the Trojans, which implies a place for Turkey in European culture. But in the last twenty years since Erdoğan came to power, a Neo-Ottoman and Islamist narrative emerged, one that is in fact simply a reversal of the grand narrative of the West.

However, Mac Sweeney does not present a picture of Western civilization simply as gloom and doom, as it was common in European philosophy during the postwar years, blaming Plato and Aristotle for the concentration camps. This is in fact not different from the false Eastern empire of Erdoğan, which simply turns the old narrative upside down, without changing its fundamental tenets, and reinforces the underlying continuity of the West that it claimed didn’t exist in the first place. She comments about present debates in the study of classical antiquity: “There are also those who seek to eradicate the discipline entirely, objecting to its historical complicity in systems of oppression, exploitation and white Supremacy.” It seems to me, however, that the erasure of the past is in itself an act of violence, one which sits at the heart of the colonial process.

In the closing remarks of The West, Mac Sweeney however advocates for something else: Reimagining the field of historical scholarship, while acknowledging the problematic status of “classic” and “civilization”: “But above all, we are committed to uncovering and communicating how diverse, exciting, and colorful antiquity really was — much more so than acknowledged by the grand narrative of Western Civilization.”

The myth of the Trojan War, in the end, isn’t the intellectual property of the West or Turkey, or a confirmation of their superior achievements. Instead, it is a human story, made of many different parts — Hittite poetry, Babylonian and Egyptian myths, Minoan and Mycaenean art, and should always remain diverse, open to new interpretations and the heritage of shared pasts and changing futures.