Middle Eastern refugees and the small boats carrying them across the English Channel have become the new scapegoats in a country that made itself poorer.

Malu Halasa

In the early hours before dawn, people work silently in the shadows of the sand dunes. They hurry in case the growing crowd catches the attention of the French gendarmes and their prowling mobile searchlights on the coast.

It is a scene played out on the beaches around Calais. After migrants ready an inflated dinghy, many hands carry it to the water’s edge. The lights of Dover 25 miles away suggest England is closer than it is.

Someone shushes the crowd when excited Arabic voices grow too loud, interrupted by a smattering of French and English. The young men and a woman with a small child are scared, even though they’ve crossed other seas and traveled from countries as far away as Iran, Afghanistan, Iraq, Palestine, even Sudan. Some know each other’s stories. Others prefer ignorance; it is hard enough to carry your own battle scars.

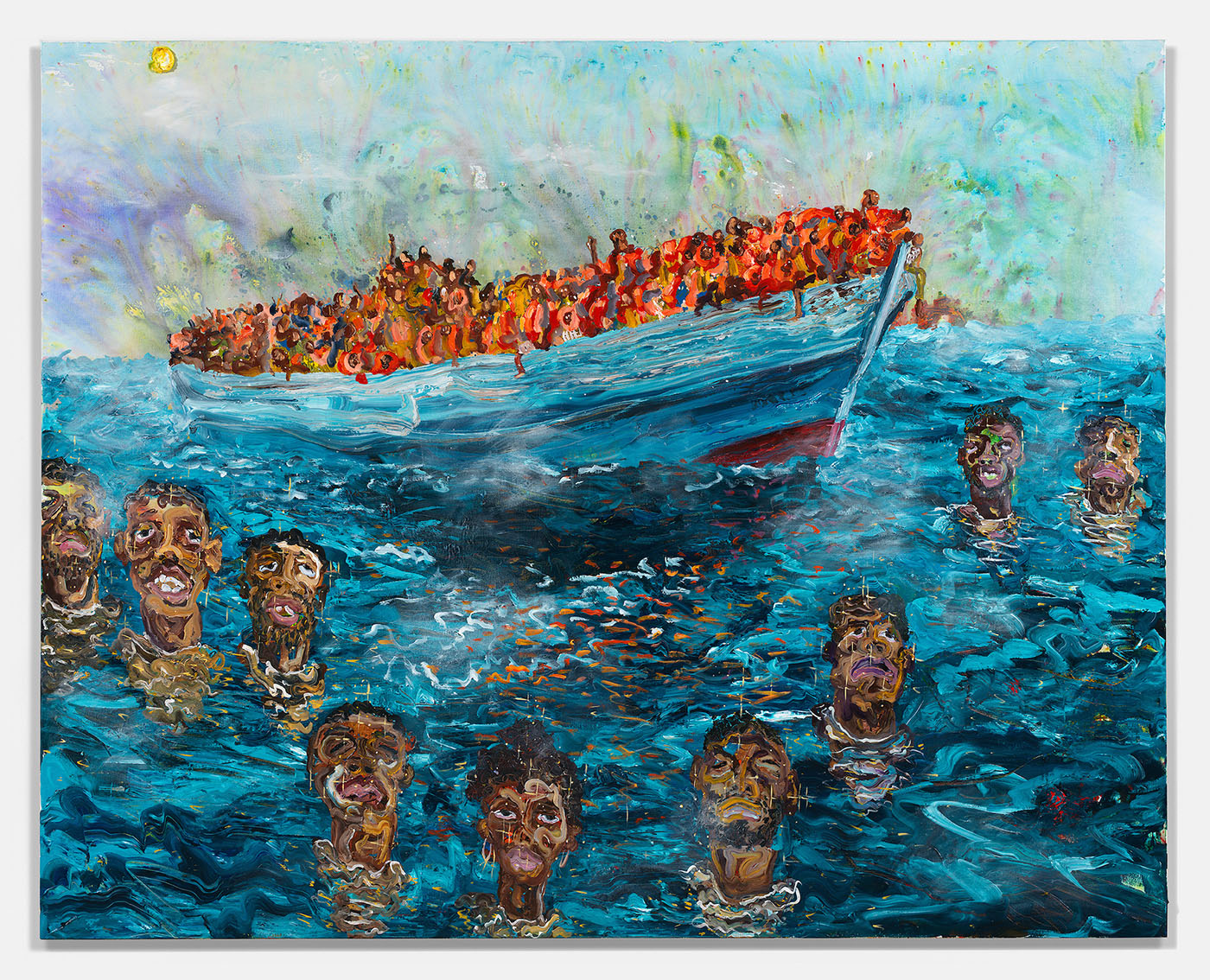

A few had failed in earlier attempts to cross the English Channel and were now trying again. For many, it was their first time. Instead of life jackets, they strapped on inner tubes from cars or vans. Almost no one was dressed for the wintery weather, and everyone was at risk of hypothermia. Since smugglers allowed them only to bring the clothes on their back, personal items of little or no worth, from plastic bags to old clothes and the odd toy littered the beach.

It made no sense when young men pushed their way to get onto the boat first. By the time everyone was on board they were squashed together. The inflatable boat, empty and light on land, had given the impression it would fly across the water to Dover. It now felt flimsy and dangerous in the sea, weighed down by its human cargo. As it pushed off, someone muttered a prayer over the revving of the outboard motor. This wouldn’t be the last entreaty from aboard this dinghy or from the others leaving from the beaches along the 62 mile stretch from Boulogne-sur-Mer to the border with Belgium. All the small boats had the same chance, whether they were organized by people smugglers or by a handful of migrants, who pooled together the little money they had and bought a glorified raft of their own. It was a crapshoot on who’d make it or not.

We will not sit back and allow the English Channel to become a mass graveyard, like the waters of the Mediterranean. —Channel Rescue

Channel Hardware

Overlooking the English Channel, towers equipped with thermal and optical imaging line the Kent coast. Electromagnetic monitors track mobile phone signals. Marine AIS or Automatic Identification System receivers follow the movement of boats; radar, too, plays its part in the arsenal of surveillance.

On eight points along the coast, in the shadows of the towers, volunteers from the human rights organization Channel Rescue also keep watch. Armed only with their telescopes and apps on their mobile phones, they survey the Channel’s choppy seas and strong tidal currents. The heavy shipping container traffic makes the Strait of Dover one of the busiest and most treacherous waterways in the world.

Steven Martin, Channel Rescue’s co-founder, observed, “When you’ve got a poorly constructed, overloaded vessel that sits low in the water and it passes one of these huge container ships, the wake that’s created can capsize a dinghy.”

Some people stranded in the water find their way onto light boats — ships with lights anchored onto the sea floor — and wait for lifeboats to rescue them. Others have not been so fortunate.

Last October 14 and 15, Channel Rescue volunteers monitored the radio, and heard a passing ship report that there were bodies floating in the water. A search and rescue operation was launched by British and French authorities. After an hour it was called off.

Martin continued, “They said they couldn’t find a boat and they couldn’t find any bodies. Ten minutes after the search and rescue was called off, a different ship called in, saying there were bodies in the water. The search and rescue operation was resumed.

“We were monitoring their communications through the night. No bodies were retrieved. The only thing that was retrieved — and we got this from a Freedom of Information (FOI) request — was an empty dinghy and an empty life raft, 14 bottles of water, and a few inner tubes.We wrote to the coroner to ask if any deaths have been reported over those days. The coroners can’t give us that information.”

Channel Rescue asked the Home Office, the British equivalent of the US State Department and Homeland Security combined. The Home Office said it would take too much time and money for that information to be provided. The charity submitted a number of other FOI requests and appealed against the Home Office’s decision. They are waiting for their FOI requests to be answered.

“So, if people were drowned that was not reported.” Martin worked in the Mediterranean, where “thousands and thousands of people have died.” (Statista has estimated that more than 2,000 people died while crossing the Mediterranean in 2022, while more than 12,000 have perished since 2014.) An epidemiologist by trade, he does Channel Rescues because he cares, but he’s also careful. Channel Rescue is a charity, with specific on shore, offshore and advocacy activities. It does not conduct search and rescue, nor is it directly in contact with people in the boats. Other organizations, Utopia 56 and Alarmphone, alert them when people are in distress in the Channel. Human rights activists have to tread a fine line, in case governments blame the messenger and accuse them of people smuggling. Amnesty International has described the trend as “punishing compassion.”

Despite the countries and organizations watching the Channel, the numbers of people who have drowned there are unknown. Another small boat capsized in the Channel in December last year. Four men, two Afghans and two Senegalese, drowned. Thirty-nine people were rescued, including a dozen unaccompanied children.

“We also suspect that more people died in the December 14 drowning than what has been reported. Basically, the numbers don’t tally up from the government’s side.”

A Mockery of Brexit

The small boats make a mockery of a key pledge of the 2016 Brexit referendum — to take back control of British borders. Since then, successive Tory governments have come up with draconian measures to stop people from even attempting the journey. One proposal to send migrants seeking asylum to Rwanda has been temporarily paused by challenges in the UK courts, and by the projected cost of the scheme. Rwanda only has the capacity to take at most 200 asylum seekers. The country started to oust victims of genocide from the hostels in Kigali, and so far the UK taxpayer has paid £140 million pounds for a scheme that hasn’t yet worked.

Last year, the British government announced that the UK Navy and Border Force patrol boats would push the small boats back into French territorial waters, thereby forcing the authorities there to deal with them.

Mounting a legal challenge, Channel Rescue joined with human rights groups Freedom from Torture and Care4Calais, and the Public and Commercial Services Union (PCS), which represents UK Border Force employees responsible for border and immigration control. Days before the four could press their challenge against the Home Office’s pushback plan, it was abandoned.

According to Home Office figures for 2021, 28,526 people came over in 1,034 small boats from France. By 2022, 1,109 small boats brought a greater number of people, 45,755. Home Secretary Suella Braverman predicted 65,000 would come in 2023. The rising numbers reflect a failure in government policy to provide safe passage for refugees. People seeking asylum in Britain, if they’re not Ukrainian or from Hong Kong, must physically be in the country before they can make a claim. Now new laws will prevent those arriving in small boats from even applying.

In the House of Commons, Braverman called the boats “an invasion.” She added, “Let’s stop pretending they’re all refugees in distress.”

The fact is, their nationalities and numbers prove her wrong. According to the Refugee Council an estimated 34,461 people who made the crossing in 2022 came from seven countries: Albania, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Eritrea and Sudan. Moreover, four in ten of those who crossed the channel came from just five countries — Afghanistan, Iran, Syria, Eritrea and Sudan. Three of those — Afghanistan, Syria and Eritrea — had asylum grant rates of 98 percent and the other two are 86 percent and 82 percent.

After April 2022, fewer small boats landed on English beaches. Intercepted in the Channel by the Navy, they were and still are being taken to the short-term holding facility Western Jet Foil, where the occupants of the small boats disembark before they are sent to Manston migrant processing center in a disused airbase, in Kent, a county southeast of London. If people fleeing war-torn countries thought they were coming to a more humane place, Manston soon shattered their illusions.

By October, the center was handling over twice its official capacity of 1,600, and began suffering from outbreaks of diseases like diphtheria, caused by poor sanitation and overcrowding. Manston had few facilities for children, and women slept next to men to whom they were not related. There were reports of racial abuse, assault by guards and drug use, not to mention bureaucratic glitches. A busload of refugees from Manston was dumped in central London, with nowhere to go. The Prisons and Probation Ombudsman, which oversees the treatment of individuals detained under the UK Immigration Act, is investigating the death of one man held in the center who later died in hospital. Manston proved unsafe for both the refugees housed there, and the people employed to look after them.

Again, the Border Force union — the PCS — joined forces with another charity, this time Detention Action. The two bodies issued the first legal action against Home Secretary Braverman. Their charge held her personally responsible for the conditions in the processing center. In less than a month, Manston was cleared. Braverman did what her predecessor Priti Patel under Boris Johnson refused to do: She arranged wholesale temporary accommodation for migrants in hotels across the country.

It is a policy that has been an unmitigated disaster for unaccompanied refugee minors and vulnerable child asylum seekers. In January, Immigration Minister Robert Jenrick admitted that since 2021, 200 children have gone missing from these hotels. Coastal resorts in southeast England were targeted. According to a statement issued by the Sussex police, “Since the Home Office began housing asylum seekers in hotels in Brighton and Hove in July 2021, 137 unaccompanied children have been reported missing. Of these, 64 have been located and 72 remain under investigation …”

Two minors missing from their area were found more than 200 miles away in Manchester to the north. After a sting operation in a neighborhood of the city known for selling counterfeit goods, Greater Manchester police discovered abducted child asylum seekers working for organized criminal gangs.

An Invigorated Hard Right

Not far from Manchester, the Suites Hotel on Merseyside is the only 4-star hotel in the area. Pictures on the internet advertise a luxury spa. The hotel events room was used for weddings. Families planning to visit the lions, tigers, zebras and giraffes at Knowsley Safari Experience were given a special rate at the Suites. That was before the Home Office requisitioned the hotel for asylum seekers.

Outside the Suites Hotel, on the night of Friday, February 10, an anti-immigration riot broke out. The fence in front of the hotel provided little protection for asylum seekers, who were told by the Home Office to draw their curtains, shut their windows and lights in their rooms, and stay inside. On the streets, amid chants of “Get them out!” a police van was set on fire. Activists from Care4Calais in Knowsley gathered for a counter demonstration in support of the migrants. The pro-asylum group later marveled at the military precision of the men in hoodies who were determined to create havoc and spread hate. Carrying hammers and throwing fireworks, they formed three groups and surrounded the police. Fifteen people were arrested, including a 13-year-old boy.

Probable cause, still under investigation by the Merseyside police, is a 30-second video on social media. A man with a foreign accent stops a local girl, in school uniform. She asks him, “How old are you?” After he says he’s 25, she admits she’s 15. He asks for her phone number, to which the schoolgirl politely demurs in a Liverpudlian accent: “No, I’m sorry, you don’t do this in this country. You go to jail.”

The encounter filmed on the teenager’s phone, has been watched several hundred thousand times on Twitter, YouTube and TikTok. The Daily Mail has since identified the man as Egyptian. He has been moved from the area.

A week after the unrest in Knowsley, leaflets appeared that targeted the supposed threat of the migrants in boats. Some bore the motto: “You pay, migrants stay.” These were distributed to residents in Dunstable, 30 miles north of London, before a town meeting about the closure of a popular local hotel, which signed a lucrative contract with the Home Office to house migrants. (Ironically it is the hotels the government pays to house migrants that have been making a reported £6.8 million a day — as opposed to the migrants who are not allowed to work, as they wait for their asylum status to be determined.) The next day, 125 miles away from Dunstable, clashes between the police and protestors erupted outside a Holiday Inn, in Rotherham, in South Yorkshire.

The anti-fascist group, Hope Not Hate, monitors the activities of the far right. People posing as journalists gained entry into the hotels accommodating asylum seekers 253 times last year — double the figure from the year before. Once inside, pseudo journos filmed themselves threatening occupants and staff — abuse that was posted on social media. A “white pride” organization, Patriotic Alternative, has been leading anti-refugee rhetoric online, and also in-person at protests in Newquay in Cornwall; Cannock in Staffordshire; Skegness in Lincolnshire; Seacroft in Leeds; Hull in East Yorkshire; and Erskine and Glasgow in Scotland. These are the communities choosing between heating their homes and eating, where nurses, teachers and policeman have been forced to use food banks because of falling real wages due to the country’s 10.1 inflation rate.

Home Office Failure

Hamid Bahrami is an Iranian human rights activist. He entered the UK illegally and gained asylum status in 2018. As a commentator and analyst on the Middle East, in Glasgow, Bahrami is no stranger to controversy.

“I was speaking with someone who is campaigning to send asylum seekers to Rwanda. I told him: If the UK government wants to decrease the number of those illegally coming to the UK, then you should campaign to bring about change in Iran. For example, we have been asking the UK government to proscribe the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps as a terrorist organization. But those who campaign for sending asylum seekers to Rwanda are against this.”

Bahrami was arrested in Iran for collating human rights abuses and sending this information abroad. After he spent a month in solitary confinement in Isfahan Central Prison, a guide took him over the border to Turkey. There, he met another Iranian who knew people smugglers, and the two traveled from Greece to France, by truck, in one week. They met a handler in Dunkirk, who smuggled them onto a truck carrying baskets of lettuce. He, his Iranian companion, and two Vietnamese stood for the entire 12-hour trip. When the GPS on one of their phones said they’d passed London, they banged on the vehicle’s walls and doors. The driver, unaware of them, called the police, and the police freed them. Bahrami spent the next three years convincing the Home Office he had a legitimate claim to seek asylum in the UK. He now writes a blog for the Times of Israel.

“Because I was a political case, it was complicated.” Despite his experiences, he believed seeking asylum was easier five years ago than it is now.

What changed?

Journalist Nicola Kelly writes on UK immigration and asylum for The Guardian. “The process of claiming asylum has become more complex, which is in large part down to the asylum backlog, which has led to huge delays in the system of up to three years. The Home Office isn’t recruiting enough, or experienced enough, staff, and is then failing to provide adequate training. The result is that most caseworkers leave quickly, so the backlog mounts even further.”

In the eight months since June last year, the backlog of Home Office cases awaiting asylum decisions has grown from 92,00 to 160,000.

Kelly continued, “Added to that, the department has become very much more defensive and hostile, not least in policy terms. We see that, of course, with the Rwanda deal, but also in the rhetoric, stoking fear and hatred, which has led to a spike in far-right attacks in recent weeks. The Home Office repeatedly says the asylum system is broken, but is doing very little to fix it; instead putting its efforts into headline-grabbing policies rather than resourcing it sufficiently.”

At the time of writing this article, the Home Office announced that it will replace face-to-face asylum interviews with an 11-page questionnaire. This will be given to 12,000 refugees who applied for asylum before July last year, who came from countries with high success rates for asylum applications — Afghanistan, Eritrea, Libya, Syria and Yemen, which are all upended by war or civil strife. Asylum seekers will be given 20 days to fill out the questionnaire in English or risk refusal. By removing human interface at the Home Office, does that mean an algorithm or a chatbot is deciding UK asylum policy?

However, two nationalities have been encouraged to come to Britain, and some say that is because these groups are considered socially or economically acceptable. On the first year anniversary of the UK’s Hong Kong overseas scheme, Care4Calais included stats with a timely tweet: 144,576 visas were offered to people from Hong Kong; 208,304 visas to Ukrainians. The charity then asked: “So why are we so afraid of 45,756 people in small boats from the rest of the world?”

The English Love Animals

The words reporters used to describe the 2021 fall of Afghanistan — “chaotic,” “helplessness,” “another Saigon moment” — didn’t capture the full horror. That was left to social media, and real-time footage of panic-struck crowds, men in shalwar kameezes, women in headscarves, with clinging, terrified children, as they surged onto the tarmac, and fought to get on planes leaving Kabul airport.

During the UK evacuation from Kabul, Operation PITTING — one plane that wasn’t supposed to take off — was given last-minute permission by the Ministry of Defence. It was filled with 94 dogs, 68 cats and 67 animal carers and paid for by Nowzad, an animal charity run by “Pen” Farthing, a former Royal Marine. Leaked and heavily redacted emails showed the animal rescue was approved by then Prime Minister Boris Johnson. The influence of the Prime Minister’s wife, a noted animal lover, is not obvious but a matter of speculation.

According to Farthing’s letters posted on the Nowzad website, both the animals and their carers now enjoy a new life in Britain. Meanwhile Afghans, including teachers, staff and independently contracted security guards who worked for the British Council, and journalists employed by the BBC, are still in hiding from the Taliban, which considers people employed in any capacity by the UK government and its associated agencies as collaborators who should be killed.

Till this day the security guards await last-minute Home Office security clearance. The journalists took their fight through the UK courts. In February, they successfully challenged the rationale behind the British government’s refusal to let them apply to the Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme, another ineffectual program. The Guardian’s Nicola Kelly found out it hasn’t brought in one Afghan since the scheme began in January. Government ministers “were showing,” according to sources speaking to her, “a ‘toxic combination of incompetence and indifference.’”

Even those Afghan translators and military personnel evacuated to the UK during Operating PITTING, allowed to stay because they qualified for an earlier government scheme, the Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy, fall victim to Home Office whims. Given little notice last month, they were uprooted from the lives they and their families established in London. They were relocated to hotels closer to those parts of the country where refugees have been targeted and made to feel abused.

Still, the question remains: What fate awaits Afghans, whose lives are in real and constant danger from the Taliban? Say they worked as teachers for the British Council in Kabul and the only way they can reach UK shores is “by irregular means” — the government’s euphemism for the boats from France.

Channel Rescue’s Steven Martin has no doubts. “In theory they could be deported to Rwanda.”

On a clear day, the clock tower in Calais is visible from the Kent coast. When the waters of the English Channel are calm, and the weather clement, more small boats arrive.

Be reasonable, doesn’t Britain do enough sending countless tons of arms (and cash?) to Ukraine? Isn’t it more important to kill people than to save their lives? I can’t believe I used to admire “Great” Britain. But that was long ago and in another country.