Savages by Abdullah Chahin — written in Arabic and published by a major press in Lebanon last April — is premised on the conviction that he has cracked open the Syrian quagmire. In this review, Fouad Mami argues that it is not only non-Syrians who often misunderstand Syrians’ sacrifices, and that a Syrian might wreak as much damage as an Orientalist or neo-Orientalist.

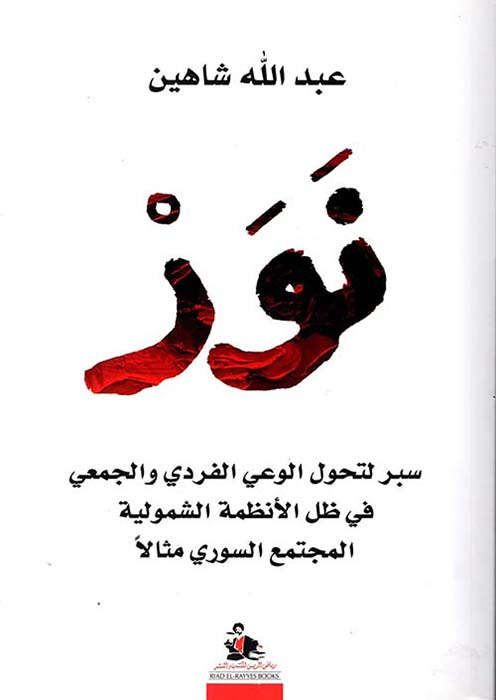

Savages, Probing the Transformation of Individual and Collective Consciousness under Totalitarian Regimes: Syrian Society as an Example, by Abdullah Chahin,

Nawãr/Riad El-Rayyes Books 2022

ISBN: 9789953217482

Fouad Mami

Abdullah Chahin is a Syrian medical doctor practicing in the United States. He has degrees in Islamic thought and artificial intelligence among other subjects. His book, Savages, Probing the Transformation of Individual and Collective Consciousness under Totalitarian Regimes: Syrian Society as an Example, grapples with the practice of otherization of Syrians by Syrians: elites of other elites, ordinary workers of other people. The habit of reducing others to nothingness and or insignificance can lead one to conceptualize them as savages. This mis/conceptualizing practice, Chahin claims, has been a cultural paradigm. Political repression is but an expression of this paradigm. Indeed, this habit facilitates genocidal killings, as with the dropping of barrel bombs on outdoor markets by the regime, or atrocities by ISIS during the war in Syria, which erupted in 2011 and remains ongoing.

Undeniably, Chahin asks the right set of questions. For instance, how is it possible for a Syrian prison warden, a security officer, or even a hospital doctor to torture other human beings during the day and return afterward to his family, kiss his children, and sleep with his wife? With Chahin, there is a banality-of-evil type of questioning, as famously put by Hannah Arendt. In order to swallow such a contradiction, something must beset the core of the Syrian self and render it sick to the marrow. The narrative that demonizes others as savages has been around for millennia but has taken an especially intense turn during the reign of the two Assads. Still, in Chahin’s view, it is not only wrong, but criminally misleading, to put the blame only on the Assads, the political elites, or their nemeses from the so-called opposition.

Decades of a generalized practice of otherization have resulted in a massive failure: a failure that is both moral and intellectual. Chahin — he never tires of repeating — does not aim to impart moral lessons. Instead, he seeks to clarify that when victims of repression internalize this otherization, the savagery is just as pernicious.

It follows that in consequence of such othering and alienation, Syrians have become incapable of building a viable polity. Chahin claims to have experienced this generalized societal distrust and failure in the relief and humanitarian work he was charged with undertaking in free zones, those areas liberated from Assad’s rule in 2013:

“In collaboration with several experts in fields such as micro-economy, human leadership, and durable development, we planned in 2013 a small developmental project called Mihãd. The point of the project was the building of individuals’ set of skills, precisely the ones pointed out by experts as well as on-ground activists in the liberated areas. Even though the awareness of the lack of training comes from the very people that applied for funding, we noted that interaction was almost inexistent … from over 200 people who registered for the event, only 10 people attended the first workshop. The remaining workshops did not witness more than five attendees…” (p. 175)

The people’s readiness to sacrifice what was dearest to them explains why ordinary actors were and hopefully still are light years ahead of intellectuals reporting on the revolution.

For Chahin, this lack of participation is catastrophic. The reversal of what he sees as a solid opportunity to build a viable future for aid applicants he interviewed and which his organization financed convinced him that ordinary Syrians are beyond redemption, given their current ways of perception and making sense of the world.

The book unfolds in four uneven sections. The first has 15 chapters. The second is divided into two chapters, the third contains six chapters, and the fourth also has six. All adhere to a blogging style of writing more than to that of a book addressing a single and well-delineated problématique. The first section attempts to account for Muslims’ fall from grace; it traces Muslims’ historical (or imagined) leadership of the world from the Middle Ages to the humiliation they experienced during the colonial and postcolonial periods. Interestingly, Chahin views the postcolonial as an extension of the colonial period. His subject near the end of the first section is the whole colonized world: Africans, Asians, and others. Political independence, which Syria gained in 1946, has only brought to power imitators who mimic colonial rulers. The latter had ushered in an exceptional style of governance: rulership without responsibility. Yet why other postcolonial polities did not degenerate in the Syrian way, culminating in the post-2011 collapse, Chahin does not specify.

The second section introduces variations of savagery in practical life situations drawn from Syria. This section is the strongest part of the book. The third section explores further iterations of the savage. In the fourth section, the author reiterates the same litany of the Syrian miasma: what he takes as further disfigurations of the psyche, such as selfishness and vengefulness.

Chahin insists that in exposing the societal ills besetting Syrians, the likes of which, in his opinion, guaranteed the reversal of the rosy promises of their revolution, his aim has never been self-flagellation as an Arab or Muslim. According to him, there are enough pseudo-thinkers around who engage in such a practice. His intention — he keeps noting — is to provide criticism that uncovers the subterranean causes for the faltering of the revolution and its militarization. Whoever thinks that responsibility lies only with Assad, his clique, or even the corrupt political establishment as a whole is fundamentally wrong. According to Chahin, Assad and Assadism only formalize an existing Syrian culture that leads to repression and the savage denial of the humanity of the other. Only in teasing out the minute components of this monstrous culture, elements of which include male chauvinism, complex ignorance, nostalgia for nostalgia, and an endemic incapacity for trust and teamwork, will one be in a position to unseat the Leviathan and build common humanity from scratch.

There is no doubt that Chahin’s intentions are pure. Nevertheless, in misery he sees only misery. And despite his claims that he is examining the deep causes of the Syrian moral collapse, he remains unable to scratch the surface of what he purports to examine. Chahin does not draw viable distinctions between the visible and the invisible — the subterranean determinant or what Hegel calls the Geist. This creates much confusion when it comes to trying to understand the complexities in Syria. Material reality and living conditions dictate the life choices and thinking of individuals and communities, not the other way around.

It is not like nothing is interesting in the book, but Chahin’s approach ruins the few insights he has. The way these insights are interspersed throughout ruminations and litanies in the first and third sections reduces them to a hotchpotch of half-digested and borrowed ideas from junk science, folk wisdom, motivational psychology, and self-help literature. Chahin’s trust in intellect as a seat of reality together with the primacy of the mind turns him into a depressive reformist, unable to seize the radical logos in the Syrian uprising of 2011. How else to account for his overlooking the revolution’s sublime early days, the exceptional work of the tansiqiyyat/local councils, and the fact that revolutionaries would have tipped the balance of material forces in their favor had the Russians not intervened in the autumn of 2015?

Even with the situation in Syria having degenerated into mass slaughter, the revolution still holds out hope. The people’s readiness to sacrifice what was dearest to them explains why ordinary actors are light years ahead of intellectuals reporting on the revolution. The kind of thinking espoused by Chahin and the so-called intellectuals like him turns them into counterrevolutionaries by default because they seem to say that not only was the revolution destined to fail, but that its failure was the result of the revolutionaries’ in-built deficiencies. While reading Chahin’s ruminations over the degeneration of the revolution, I could not shake Hegel’s remarks in the preface of Phenomenology of Spirit (1808) or the notes on evil consciousness later in the book. Hegel points out that ego, when embraced as a mode of analysis, is destructive. Chasing the limelight, armchair intellectuals overlook the real movement of history. As such, they only uncover the depressive and neurotic parts of themselves. True understanding begins with humility before those people who are better placed to offer insight, if not razor-sharp analysis. Reality is not what a far-off intellectual simply imagines it to be.

In dogmatically preaching that the core of the Syrian self is ill — even rotten, hence the unbounded catastrophe — culturalist approaches of the kind championed by Chahin freely serve the Butcher of Damascus. Overlooking the Syrians’ logos, as instantiated through movements such as Al-Shaab Al-Souri Aref Tariquh (The Syrian People Know Their Way), frames the uprising as a cultural quest for some mysteriously lost identity. Yet the uprising remains an expression of a historical propulsion for total and uncompromising emancipation on the part of a long-oppressed people.