Irit Neidhardt

The Arab presence in Berlin has been continual since at least the end of the 19th century. Only in recent years has this history begun to be written[i]. Some of the authors who trace biographies of Arab individuals in Berlin initiated official memorial plaques, with which the municipality commemorates people and events that were significant for the city. Since 2014, three such plaques have been added to remember Arab Berliners. Among them is the Egyptian physician Mohamed Helmy (1901-1982), who came as a student in 1922 and stayed in Berlin for the rest of his life. In the late 1930s he was arrested twice by the Gestapo, before hiding several Jews from their Nazi persecutors[ii]. Another is Palestinian artist Jussuf Abbo (1890-1953, Yussuf (Abu) al-Jalili), who lived in Berlin between 1911 and 1935. He participated in the progressive art movements of his time and his work was exhibited in top galleries until the Nazis removed it as “degenerated” in 1937[iii]. The third is Mohamed Soliman (1878-1929), who traveled across Europe with a group of artists from Egypt around 1900 and stayed in Berlin. In 1906 he opened one of the first cinemas of the city. Soliman also owned the theatres in the famous Kaisergalerie and directed the “Oriental Department”[iv] of the Luna Park Berlin in Halensee[v].

A contemporary of theirs was the merchant and gramophone tycoon Michel Baida. While much has been written about Baidaphon, the international record company that Baida ran together with his brothers Pierre/Boutrous and Gabriel/Jibril from their Berlin headquarters, little is known about Michel Baida’s life. Who was Baidaphon’s strategic mastermind? What traces did he leave in Berlin and what was his role in the anti-colonial struggle?

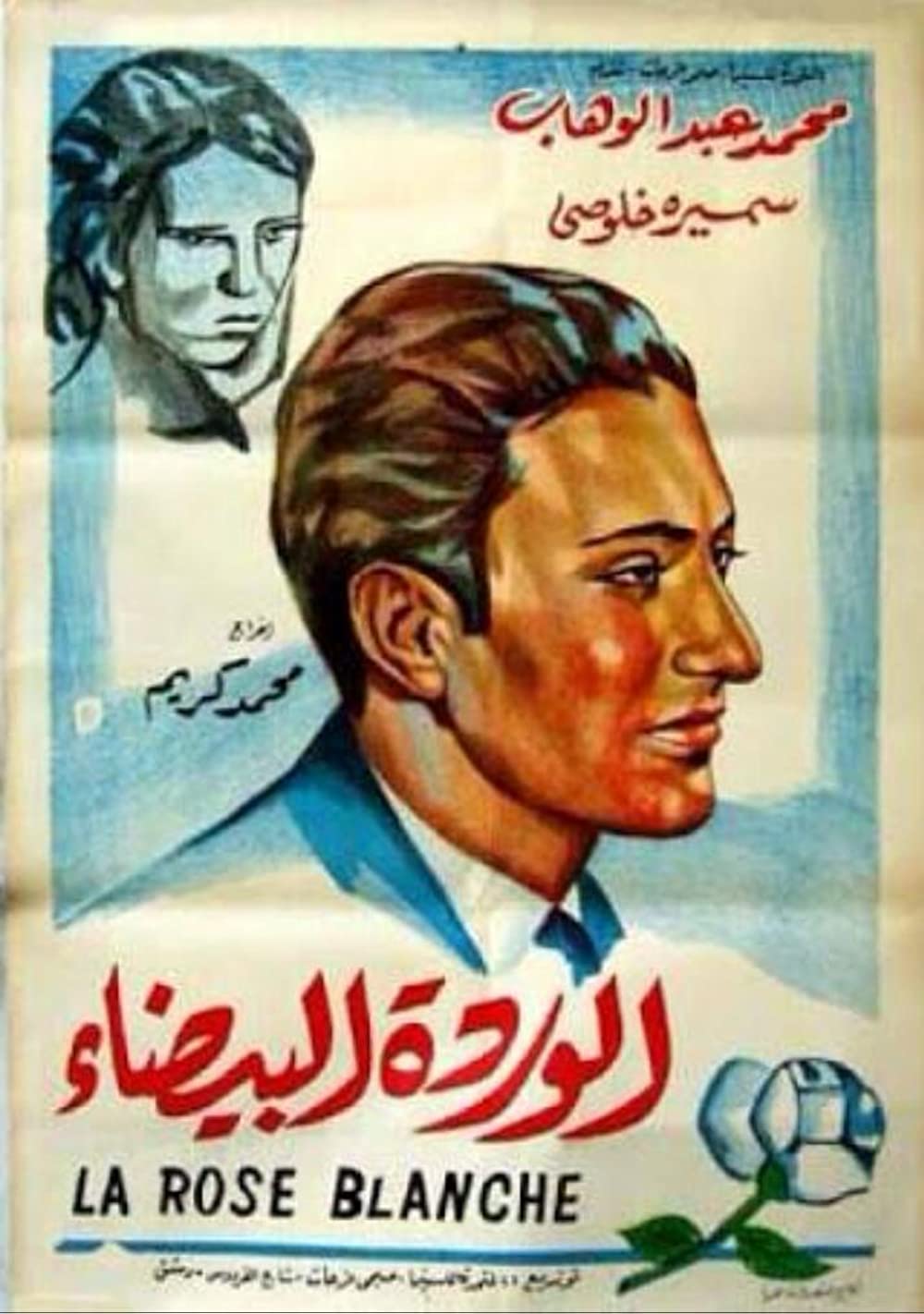

With these questions in mind, I started writing the article at hand. I had dealt with Baidaphon previously in a more general way for texts about Arab-German relations, which aroused my curiosity about Michel Baida as a person. His company recorded and sold the music of Farid el-Atrash, Asmahan, or Mohamad Abdel-Wahab, to name only some of the most iconic Baidaphon stars that millions listen to till today. Their Cairo branch, Cairophon, produced the first Arab sound movie: al-Warda al-Baida’ (The White Rose, 1932, starring Mohamad Abdel-Wahab). Yet, what interested me most was that Baidaphon produced and exported phonographs, machines that record and duplicate voices, from as early as 1912. Their fabrication and distribution were an important tool in the anti-colonial liberation struggle before the radio took over this role, the latter being studied by Frantz Fanon in his 1959 essay “This is the Voice of Algeria”[vi].

Strangely, I had never read standard biographical information about Michel Baida: when and where was he born and when and where did he die? When and why did he come to Berlin and when or why did he leave? I knew that Michel Baida is said to have been a physician, and that the trademark Baidaphon was first registered in Germany in 1912, that Baida had become extremely rich from the record business and financed the Syrian pan-Arab and pan-Islamic politician Shakib Arslan for many years[vii]. I had read that Baida presumably lost his real estate in Berlin in the course of the world economic crisis in 1932/33,[viii] as well as that Baidaphon seemingly was suspended in the 1930s and Michel Baida’s trace was lost around the same time.

I assumed that by law, as a foreigner, he might have been prohibited to exercise his profession as a physician. I wondered where a non-German’s trace vanished to during Nazi rule and why nobody appeared to have looked for him.

Being convinced that without extensive networks in Germany Michel Baida could not have built his gramophone empire, it seemed impossible to me that such a tycoon could get lost. And it is from here that I started digging deeper into the matter.

In my notes I found a memo saying that the German Federal Archives keep a file of the (Third) Reich Commissioner for the Treatment of Enemy Property running from 1941-1948 that refers to Gabriel and Michel Baida, indexed as “French assets including colonies,”[ix] which I decided to see for the text at hand. Another source I consulted was digitized Berlin daily newspapers from the 1910s till the early 1940s, the period through which Michel Baida was registered in the Berlin street directory. After viewing those sources this article had to change fundamentally and thus became an open-ended inquiry.

The sheer number of documents from the newspapers and much more so in various Berlin archives is overwhelming to an extent that it was unfeasible to see them all and visit all archives during the three weeks I had for working on this publication. Let alone sorting, analyzing and interpreting the records, most of which are in the German scripts Fraktur and Sütterlin.

In the following I start to reconstruct the lifeline of Michel Baida of whom I have never seen a photo and about whom I still do not know when he was born and when he died. Most probably his life began and ended in Beirut. He came to Germany as a Turk, a Syrian with Ottoman papers, and left as a Frenchman — that is, a Syrian national from the French colonies. According to Elie Baida, a nephew of Michel Baida and a Baidaphon musician himself, Baidaphon:

“owes its origin to five ambitious members of the Christian Bayda (Baida) family from the Musaytibah quarter of Beirut. Two of them were Jibran (Elie Bayda’s father) and Farajallah [the company’s first recording artist, I.N.]. These two brothers, who were practically illiterate, earned their living first as construction workers in Beirut. The remaining founders included their two fairly educated cousins Butrus and Jibran. Encouraged by the rising popularity of phonograph recording and by the ready talent of their cousin Farajallah, they decided to form with their cousins their own recording company. […] In their negotiations [to record and manufacture in Berlin, I.N.] the two Baidas were assisted substantially by their brother Michel, a physician living in Berlin, the fifth founder.”[x]

The first documents proving Michel Baida’s presence in Germany are two entries of Baidaphon to the trade register in 1912, one in Hamburg and one in Berlin. Baidaphon Hamburg was represented by H. Feldman & Co. and was an export and import company for musical devices and instruments as well as records. H. Feldmann worked with the Baida brothers’ companies at least until the early 1930s[xi]. Baidaphon Berlin was represented by Dr. Michel Baida, the address was Gitschinerstrasse 91 in Berlin-Kreuzberg, where the gramophone company Lyrophon was residing until it was bought by Carl Lindström AG around the same time of the Baidaphon registration. Baidaphon might have taken over the equipment. Baidaphon Berlin’s business operations were the distribution of phonographs and records, its products: phonographs, phonograph equipment, and records. In the 1920s electronic dry cells were added to the export products[xii].

A glimpse at the personal columns of the Berliner Tageblatt und Handels-Zeitung, the city’s leading newspaper of the time, gives a first impression about how Baida positioned himself in the city’s society: on January 15, 1922, Michel Baida’s marriage with Hilde Casper is announced. Becoming Ms Baida, Hilde lost her German citizenship as did all Germans who married non-Germans between 1871 and 1945, and took her husband’s nationality. Her faith was and remained Jewish[xiii]. The couple’s marriage is not registered in the civil status office in charge. This means that they seemingly did not marry in Berlin and thus their civil status affairs are not registered in town.

In Berliner Tageblatt of Christmas 1922, a donation of 2500 marks by Dr. Baida for the elderly care is announced. On December 11, 1923, a number of in-memoriam notices were published for Arthur Bodansky, director of Europe’s largest gramophone company at that time, Lindström AG. Dr. Michel Baida published an obituary in his name rather than in the name of Baidaphon. The same is the case with the obituary for Arthur Scholem on February 8, 1925, whom Baida calls “a good business friend whom I have come to appreciate and respect as a noble and honest character over the course of seventeen years.”

A note in the “Sports/Games and Gymnastics” section of Vossische Zeitung from 2 May 1933, the other major newspaper in Berlin, gives a clue about Baida’s involvement in Berlin’s Arab society.

“Funeral service for Sayed Ahmed EschThe Islamic colony organized a worthy funeral service for Sayed Ahmed Esch-Scherif, the great fighter for unity and freedom and the ally of Germany and Turkey in the World War in the Club der Auslandsdeutschen. Dr. W. Raslan described his life, His Excellency Emir Shakib Arslan spoke warm words of remembrance and Dr. Baida the Arabic obituary.”

The German Ministry of Foreign Affairs certifies in a document from 1926, that Dr. Baida had been a resident of Berlin for 18 years, had, as an industrialist and merchant, mainly business relations to the “Orient” and that his reputation relating to business was good[xiv]. A draft for another attestation from 4 May 1929 reads:

“The Syrian national Dr. Michel Baida, Berlin N.W.7, Mittelstrasse 55, is known to the Foreign Office as one of the wealthiest and most respected local Oriental merchants and has been residing in Germany since almost 21 years. He enjoys the best reputation among his local compatriots and has repeatedly rendered valuable services to the [German, I.N.] Foreign Office due to his commercial experience in the Orient. At the same time, he is the Hedjaz government’s ombudsman for economic affairs” (the last sentence being crossed out)[xv].

By that time Michel Baida had founded several property management companies in Berlin as well as Nar for Coal Trading and Lighting Technology GmbH (Light Ltd). Baidaphon had offices and representations at least in Beirut, Cairo, Berlin, Alexandria, Baghdad, Basra, Casablanca (headed by Baida’s nephew Théodore Khayat), Jaffa, Jerusalem, Kermanshah, Mosul, Tabriz, Teheran, Tripoli, and Tunis as letterheads and correspondence with the German Foreign Office as well as the Baidaphon Catalogue Tunis from 1928 show.

In the Maghreb, Baidaphon was one of several Arab record companies. While the radio was the main medium of the European settlers, the Arabs and Amazigh listened to records, increasingly to Arabic music. Especially the Baidaphon music was known for its nationalistic lyrics. In May 1930, the (French) Civil Control in Morocco was informed “that a record label in Berlin has sent phonograph records to Morocco reproducing, in the Arabic language, songs in favor of Egyptian independence which are prone to provoke unrest in the Muslim milieu”[xvi]. Not only Arab nationalism but also Michel Baida’s good relations to German officials were an embarassment to the French administration, which tried to prevent the import of Baidaphon records. Thereupon a small label named Arabic Record appeared which either pirated Baidaphon or was Baidaphon itself[xvii]. Given the Baidaphon export business of phonographs and phonograph equipment, it seems likely that they provided the production tools for this and other small Arab labels, be it to record music or political speeches. In the wake of a decree from 1938 that forbade the import of records in any language but French to Algeria, the army banned all Baidaphon records from the country’s Arab cafés[xviii].

During that same time, Baida’s Nar for Coal Trading and Lighting Technology GmbH was under attack in Germany. Two lawsuits were filed against Nar GmbH: the Combustible Inspection Agency Berlin sued Michel Baida and his business partners because Nar for Coal Trading bought coal for wholesale conditions and sold it at regular market price to Baida’s own real estate companies. A note from September 1931 by a high ranking officer at the Foreign Ministry about a private conversation with the inquisitor says that most probably Baida and partners cannot be proven to have committed a criminal offense. The inquisitor was the second judge to work on the case, his precursor was withdrawn due to prejudice after Michel Baida had complained about him at the Prussian Ministry of Justice[xix]. Standard Licht GmbH (Standard Light Ltd) from Frankfurt/Main sued Nar GmbH for product piracy. Nar’s Lighting Technology section seems to have copied petroleum lamps from Standard Licht and advertised them in their catalogues for Arab countries and Turkey, to where Standard Licht sold as well. From the dossier at hand, it is clear that Nar GmbH and Standard Licht both appealed the court order that sentenced Nar to a penalty of 40,000 marks (the average weekly income in 1932 was 85 marks). Standard Licht found the sum too low and Nar too high, and accordingly did not pay.

While all letters to the Foreign Office regarding the two law cases burst with racism, a circular by Standard Licht GmbH from January 1932 shows the dimension of the dispute. Standard Licht had sent a marshal to Baida’s private house, who confiscated furniture in the estimated value of 3830 marks. Carl Casper, Baida’s father in law, succored and bought the confiscated furniture with a price increase of 10%, which to Standard Licht looked like a swindle. The company reported all this to the Foreign office, “so that you are informed, in case these people should continue to use you against the interests of Germany and normal German trade” [xx]. In that year several houses of Gabriel and Michel Baida in Berlin were auctioned[xxi]. Yet, state institutions still protected Baida.

A year later the National Socialist German Workers Party, the Nazi party, came to power, and on January 1, 1936 the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor came into force, which deprived all Jews of their German citizenship and systematically excluded them from all participation in public life. Following the the Decree on the Treatment of Enemy Property from January 15, 1940, property and companies owned by enemies (among others citizens of France and its mandated territory) could be subjected to coercive administration. The above mentioned file in the German Federal Archive contains the financial reports of the sequestrator of one of the Baidas’ houses. Additionally, numerous files of the Baidas are kept in the archive of the Berlin Compensation Office that opened in 1949. Michel Baida, in some cases together with his brother Gabriel, claimed nine houses back, Hilde asked for restitution together with her siblings[xxii].

From the rough look I could hitherto take into the documents, Hilde Baida left Germany before 1938 and moved to Beirut. The address is Rue Damas, by Martyr Square where the first Baidaphon shop in Beirut opened around 1907. Michel Baida does not seem to have left Berlin for good yet. His last entry to the street directory dates from 1943. At the end of 1938, he registered another pictogram for Baidaphon in Germany for the business domain of producing, distributing and exporting records and record needles, the product was “discs recorded in Oriental language, music and songs”[xxiii].

In May 1952, Hilde Baida wrote to the Berlin Compensation Office and stated, amongst others, her new civil status. She was now a widow. She moved to Rue Saifi (Immeuble Asfar), a previous Baidaphon address. Her letterhead reads Etablissements H. Baida, reminding of the Baidaphon logo. She sold discs, radios, and telephones[xxiv]. The last letter I saw from Hilde Baida so far dates to 1963.

This article will be updated occasionally.

Endnotes

[i] Most comprehensive are Ahmed, Aischa (2020): Arab Presences in Germany around 1900. Biographic interventions into German history. Bielefeld, transcript and Gesemann, Frank, Gerhard Höpp and Haroun Sweis (2002): Arabs in Berlin. Berlin, Die Ausländerbeauftragte des Senats (both in German), summaries in Arabic د. أمير حمد(2009): العرب في برلين, https://sudanile.com/العرب-في-برلين-عرض-وتقديم-أمير-حمد-برل/ and اعتدال سلامه (2016): تاريخ العرب في برلين.. نجاحات فنية واجتماعية وإخفاقات سياسية https://aawsat.com/home/article/720456/تاريخ-العرب-في-برلين-نجاحات-فنية-واجتماعية-وإخفاقات-سياسية

[ii] Commemoration plaque Mohamed Helmy https://www.gedenktafeln-in-berlin.de/gedenktafeln/detail/mod-mohamed-helmy/3006 , see also Avidan, Igal (2017): Mod Helmy: How an Arab Physician in Berlin saved Jews from the Gestapo, dtv (in German); Steinke, Ronen (2017): Anna and Dr Helmy: How an Arab Doctor Saved a Jewish Girl in Hitler’s Berlin, Oxford University Press (2021), مسلم ويهودية. قصة إنقاذ طبيب مصري لأنا من النازيين (2021).

محامد ناصر قطبي (2017): طبيب مصري في برلين النازية … البطولــة والإنسانيــة، دار الكتب

[iii] Commemoration plaque Jussuf Abbo https://www.gedenktafeln-in-berlin.de/gedenktafeln/detail/jussuf-abbo/3232, https://jussuf.abbo.uk/, see also Schöne, Dorothea (ed. 2019): Jussuf Abbo, Catalogue published on the occasion of the exhibition “Jussuf Abbo” at Kunsthaus Dahlem (November 8, 2019-January 20, 2020). Cologne: Wienand (English/German), Karin Orchard (2019): Jussuf Abbo – Skulpturen.Zeichnung.Druckgrafik, Sprengel Museum Hannover (German), Arabic press about the exhibition in Beirut in 2018 http://salehbarakatgallery.com/Content/uploads/Event/8289_SAID%20BAALBAKI-JUSSUF%20ABBO-ALAKHBAR%202018.pdf

[iv] I use the official terminology of that time, which also Soliman and his contemporaries did self-evidently. This way sources can be traced, and political and cultural developments and discourses traced.

[v] Commemoration plaque Mohamed Soliman https://www.gedenktafeln-in-berlin.de/gedenktafeln/detail/mohamed-soliman/3262, see Ahmed 2020, pp. 142-151, Gesemann/ Höpp/ Sweis 2002, pp. 33-34, Kamel, Susan (2004): Hamidas Lied. Die 100 Jahre einer Muslimin an der Spree. In: Kröger, Jens/Heiden, Désirée (Hg.): Islamische Kunst in Berliner Sammlungen. 100 Jahre Museum für Islamische Kunst in Berlin. Berlin: Parthas-Verlag.

[vi] Fanon, Frantz (1959): This Is the Voice of Algeria, in: Studies in a Dying Colonialism, English in 1965, New York: The Monthly Review Press.

[vii] Arslan, Shakib (1931): Lettre de l’Emir Chékib Arslan au Journal, Lausanne, le 26 août 1931, in: Jung, Eugène (1933): Le réveil de l’Islam et des arabes, Paris: self-published, p 110.

[viii] Gesemann/ Höpp/ Sweis 2002, p 32f.

[ix] Federal Archives in Berlin-Lichterfelde, BArch, R 87/8677

[x] Racy, Ali Jihad (1976): Record Industry and Egyptian Traditional Music: 1904-1932, in: Ethnomusicology, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 23-48, University of Illinois Press, p. 40.

[xi] The Political Archive of the Federal Foreign Office, PA AA RZ 207/80562

[xii] Rainer E. Lotz with Michael Gunrem and Stephan Puille (2019): Das Bilderlexikon der deutschen Schellack-Schallplatten (5 Bände) – The German Record Label Book. Holste: Bear Family Records. On Baidaphon online https://www.recordingpioneers.com/docs/BAIDA-TheGerman78rpmRecordLabelBook.pdf, p.6

[xiii] See Jewish Directory for Greater Berlin 1931/32.

[xiv] PA AA RZ 207/78315

[xv] PA AA RZ 207/80560

[xvi] „Propaganda étrangère par les phonograph“ 30 May 1930, CAND MA/200/193 quoted as in Silver, Christopher (2022): Recording History. Jews, Muslims and Music across Twentieth-Century North Africa, Stanford University Press, p. 91.

[xvii] See Silver, p. 92

[xviii] See Scales, Rebecca (2010): Subversive Sound: Transnational Radio, Arabic Recordings, and the Dangers of Listening in French Colonial Algeria, 1934–1939, in: Comparative Studies in Society and History 2010;52(2), pp. 384–417, p. 414.

[xix] See „zu III 0 3273“ PA AA RZ 207/80562

[xx] „A.A. eing. – 6. Jan. 1932 Nm“ PA AA RZ 207/80562

[xxi] See Amtsblatt für den Landespolizeibezirk Berlin, https://digital.zlb.de

[xxii] See http://wga-datenbank.de

[xxiii] Lotz / Gunrem / Puille online p. 8

[xxiv] Central State Archive of Berlin, Landesarchiv Berlin B Rep, 025-1 Nr.:1797/55

Dear Irit Neidhardt,

Yesterday I stumbled into your article about the Baidas/Baidaphon. Wonderful well-written piece of research! Alas, the vital statistics of Michael Baida (and the others) are still missing. Today I did some searching (the BAIDA items on my website are alarmingly empty). I looked for Elia Baida (Gibran/Jibril’s son). Born on 6 Aug 1907 or 1909 in Beirut. Daughter: Madeleine Elia Baida (b. 1939, Lebanon) He moved to the USA, married a certain Marie/Mary S. on 27 Oct 1948. Children: Tamam (female) and Gibran. Was naturalized in 1951. Elia died in 1977 in Tompkins, NY. But you may already have done this work. What else is on offer? Picture of Elia and Farajalla (from record label).

How about combining forces? Thanks a lot for your article.

Hugo Strötbaum