I am here and I am staying. F**k you!

Necati Sönmez

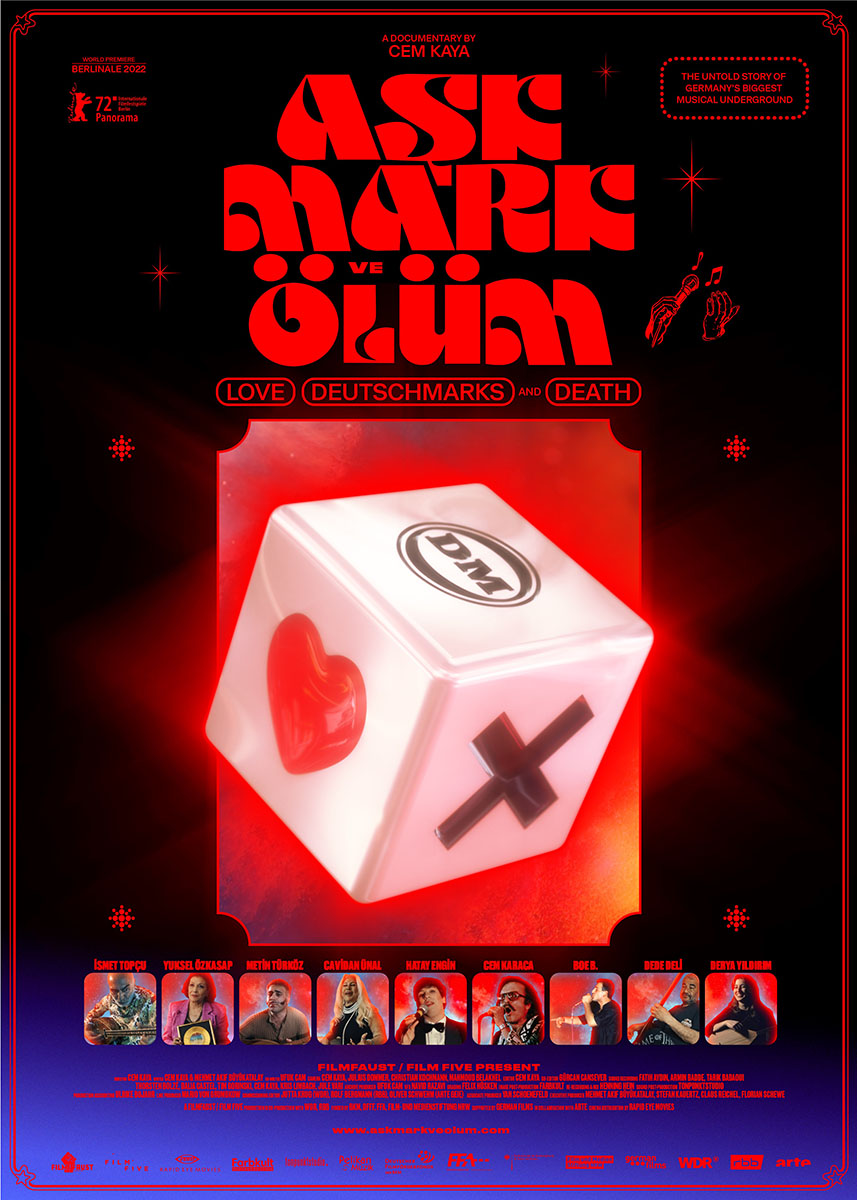

For years, Fatih Akın’s Crossing the Bridge: The Sound of Istanbul (2005) has been the sole globally known documentary about music originating from Turkey. Now we have another film which has become immensely popular — even before its theatrical release. Love, Deutschmarks and Death is the latest from Cem Kaya, who is, like Akın, a German-Turkish filmmaker. Not only did it win the Audience Award for Best Documentary in Panorama at Berlinale 2022, receiving a standing ovation during its world premiere, but Kaya’s doc has also been highly acclaimed in all the festivals in which it has participated so far, adding many more awards to its collection. The film has yet to open in cinemas in Turkey and Germany, yet has already been seen by thousands of festivalgoers.

While Akın’s film was a glance at the Istanbul-centered music from a German perspective (embodied by both the director and Alexander Hacke, the main character of the film), Kaya’s archive-based documentary is an up close and personal examination of Turkish music produced and consumed in Germany. As much as the former is a kind of a logbook of a curious tripper, the latter is more like a compact documentation of a largely unknown musical history, in an informative but at the same time entertaining and dynamic way. In fact, it may not be really rewarding to compare the two films, as they have little in common content-wise, apart from the fact that, as high-budget productions, they both indicate the German interest in Turkey-centric music, and will both probably remain the most popular documentaries on the topic.

Following the signing of the German-Turkish Recruitment Agreement on October 30, 1961, hundreds of thousands of so-called “guest workers” (Gastarbeiter) from Turkey made their way to West Germany, which was facing a labor shortage after World War II. Initially, the “guests” were supposed to return home after a limited stay. However, things did not go as planned, as their family members were allowed to join the workers. Many of these guest workers and their families ended up staying in Germany for good. Even though similar agreements were signed between Germany and, for example, Italy, Greece, and Yugoslavia, the Turks — and Kurds from Turkey — would eventually become the largest immigrant community in the country, with a population of about three million. As a matter of course, these people brought not only their labor, but also their culture and traditions.1 Their socio-cultural visibility (and audibility) in this new home called Germany would manifest itself at best on the music scene.

Coinciding with the 60th anniversary of the Recruitment Agreement, Love, Deutschmarks and Death is an intriguing soundtrack to this long history of immigration. Unlike with many films, here the score does not determine the mood, but the other way around — the social mood determines the music. More precisely, the film offers, through the music industry, an alternative look at the lives of those recruited to take on menial jobs in Germany over the past six decades.

A prodigious story with numerous charismatic characters yet a sole protagonist at its core, Love, Deutschmarks and Death uses song as a tool for the underrepresented to speak out. For the majority of the German population, the kind of music in question is nothing more than noise heard from the loudspeakers of a car driven in the streets of Berlin or Cologne. Yet by means of this music, the Turkish community would establish connections between “here” (Germany) and “there” (Turkey), between the new home and the “Heimat,” or homeland. They would express their common grievances in the lyrics, including life circumstances, ill-treatment in the work place, “outsiderness,” and the overwhelming pain of separation from home and family; in other words, all the aspects of gurbet, which in Turkish literally means “state of exile,” but also refers to a strong homesickness and nostalgia. That’s how the word “Gastarbeiter” was ironically translated into Turkish as “gurbetçi” (one living away from home). When you become a “guest” somewhere, it’s no wonder that you are detached from home!

The film takes its name from a poem of the same title by Aras Ören, which was performed as a song in 1982 by Ideal, a well-known German rock band of the time. From a musical perspective, the history in question can be roughly divided into three periods, spanning three generations — 1) Love: when the emotional attachment to homeland and the grief of separation were prominent in wistful songs, 2) D-Mark: when a currency that symbolizes prosperity came to the fore, and 3) Death: when neo-Nazism is on the rise and a new kind of music reacting to discrimination, xenophobia and racism emerges.

The film takes its name from a poem of the same title by Aras Ören, which was performed as a song in 1982 by Ideal, a well-known German rock band of the time. From a musical perspective, the history in question can be roughly divided into three periods, spanning three generations — 1) Love: when the emotional attachment to homeland and the grief of separation were prominent in wistful songs, 2) D-Mark: when a currency that symbolizes prosperity came to the fore, and 3) Death: when neo-Nazism is on the rise and a new kind of music reacting to discrimination, xenophobia and racism emerges.

After a short introduction to the historical context, several faces begin to appear on screen, one after another: Yüksel Özkasap, the “Nightingale of Cologne”; İsmet Topçu, a virtuoso of electric-bağlama; Metin Türköz, a worker-turned-folksinger; Ali Derdiyoklar, who designed his own special instruments; as well as casette collecters, record producers, writers, and retired instrumentalists who still gather on regular basis in Berlin’s Hasenheide Park.

However, not all the names are economic immigrants linked to the 1961 Recruitment Agreement. For instance, there is Cem Karaca, whose story alone could be turned into a film and who was already a star on the Anatolian rock scene when he took refugee in Germany as a political dissident following Turkey’s military coup d’etat in 1980. As underlined in the part oft he film dedicated to his exile, he had to start from scratch; nevertheless, he made an epochal contribution to Turkish-German music. As touched on by the intertitles, he ultimately made the controversial decision to return home, disappointing his fans with the compromises he made with the political establishment in Turkey.

The truth is that, occasionally the political factors in this story are not as clear-cut as one presumes. No doubt the “Gastarbeiter” community was exposed to all kinds of discrimination, inhumane working conditions, labor exploitation and so on, and the music its members made was often an answer to that. On the other hand, some songs were not exempt from, for instance, a good deal of occidentalism or machismo, as evidenced by their lyrics.

Among the very interesting remarks expressed by the interviewees, there is one particularly significant statement by author İmran Ayata, who reflects on the element of racism, saying that in fact it worked as a strong motivation triggering artists to sing and say: “I am here and I am staying. F**k you!”

Eight years in the making, the documentary, a splendid example of creative montage, is based on extensive archival research and involved an incredible amount of work.3 Conversations held in the form of authentic coffee chats are intermingled with original footage from 1970s TV shows, wedding tapes, concert recordings, scenes from old Turkish popular films, etc. Thanks to the meticulous editing, all these fragmented pieces enter into a delicate and sometimes funny dialogue with each other throughout the film.

Kaya, who also edited the film, has already proved himself in the field with his previous documentary, which relied to a large extent on archives. Remake Remix Rip-Off4 (2015), an investigation into the plagiarization culture in popular Turkish cinema during the golden age of B-movies, was a comprehensive labor of montage, remixing the images and sounds taken from these movies, which in fact copied Hollywood blockbusters. (One can only imagine the crazed amount of work it must have required just to clear the copyrights for such a documentary!)

Kaya is also no stranger to music connected with immigration. An earlier film of his, Arabeks5 (2010), co-directed with Gökhan Bulut and commissioned by Arte/ZDF, explored Turkey’s popular music aesthetic known as “arabesk” (arabesque), which emerged in the wake of the internal migration from eastern rural provinces to the big western cities, particularly İstanbul. Hence, before economic migration to Germany there was internal migration during the 1960s, and “arabesk” represented the musical output of that social development.

As seen in Love, Deutschmarks and Death, the diversity of the music scene of Turkey is readily apparent in the case of the immigrant community in Germany, where the genres vary from arabesque to protest rock, from soft pop to disco, from rap to hip-hop. What brings all these musical traditions together are the common socio-political struggles of the people singing them, and the people about whom they are sung —the fight for better working/living conditions, women’s struggle for their rights, the challenges facing labor organizations, etc. Music became an outlet for those striving for a better life on any of these fronts.

One can’t help wondering whether the production and consumption of this music might have helped forge a collective memory, and whether it was helpful in easing the burden of life. Has this music functioned as a survival kit for immigrants from Turkey in Germany? Albert L. Lloyd, a folk singer and key figure in the British folk music scene of the 1950s and ’60s (and a member of the British Communist Party), wrote in his magnum opus, Folk Song in England (1967):

“Generally the folk song makers chose to express their longing by transposing the world on to an imaginative plane, not trying to escape from it, but colouring it with fantasy, turning bitter even brutal facts of life into something beautiful, tragic, honourable, so that when singer and listeners return to reality at the end of the song, the environment is not changed but they are better fitted to grapple with it.”6

The mad dream of İsmet Topçu, the likeable character who opens and closes Kaya’s film, is to be hired by NASA and asked to play his instrument on the moon. He seems to believe that outer space is where he can experience the ultimate freedom. Topçu may be right. Still, it is not hard to imagine that he would feel freer even once he is back from the space voyage.

Endnotes:

1) “We wanted a labor force, but human beings came,” as Max Frisch would put it later. For a detailed account of the historical background, see here.

2) “Aşk Mark ve Ölüm” by Ideal.

3) “Remake Remix Rip-Off” (2015) by Cem Kaya.

4) In one recent interview, Kaya refers to Bruce Conner’s “Marilyn Times Five” (1973) as one of his all-time inspirations.

5) The term “arabesk”(arabesque) is deliberately misspelled in the title as “Arabeks,” which is the way it is usually pronounced. “Arabeks” (2010) by Gökhan Bulut and Cem Kaya.

6) A. L. Lloyd, “Folk Song in England” (1967), pp. 180.