Syrian architect Mohamed Mufti held his first exhibition in France in 2003. Soon after, his work was featured in galleries and museums in France, Italy, Finland, Turkey, Lebanon, Syria and the United Arab Emirates. His work depicts themes and reflections on Damascus and Beirut’s political and social scene. He is currently living in Lebanon.

Nicole Hamouche

With only his paintbrush and T square, Syrian architect and artist Mohamed Al Mufti settled in Lebanon in 2012, a year after the outbreak of war in Syria and the disillusionment that followed the first stirrings of a revolution aborted in blood. At the time, Beirut was not yet marred by violence and deprivation, and being in exile sometimes allows for talent to explode, forcing one to look within oneself for resources. After a few difficult years in Lebanon, during which he concentrated on teaching and his art, the prolific artist’s career took off. He exhibited in Beirut and Paris and contributed to numerous group shows in Europe. He has a lot to say and to remember, because everything in 20th and 21st-century Syria and Lebanon is left to either fade away or rot. Pre-occupied with memory gaps means that collective memory, its symbols, and their reinterpretation are at the heart of his exploration; for he believes that he who has no memory has no future.

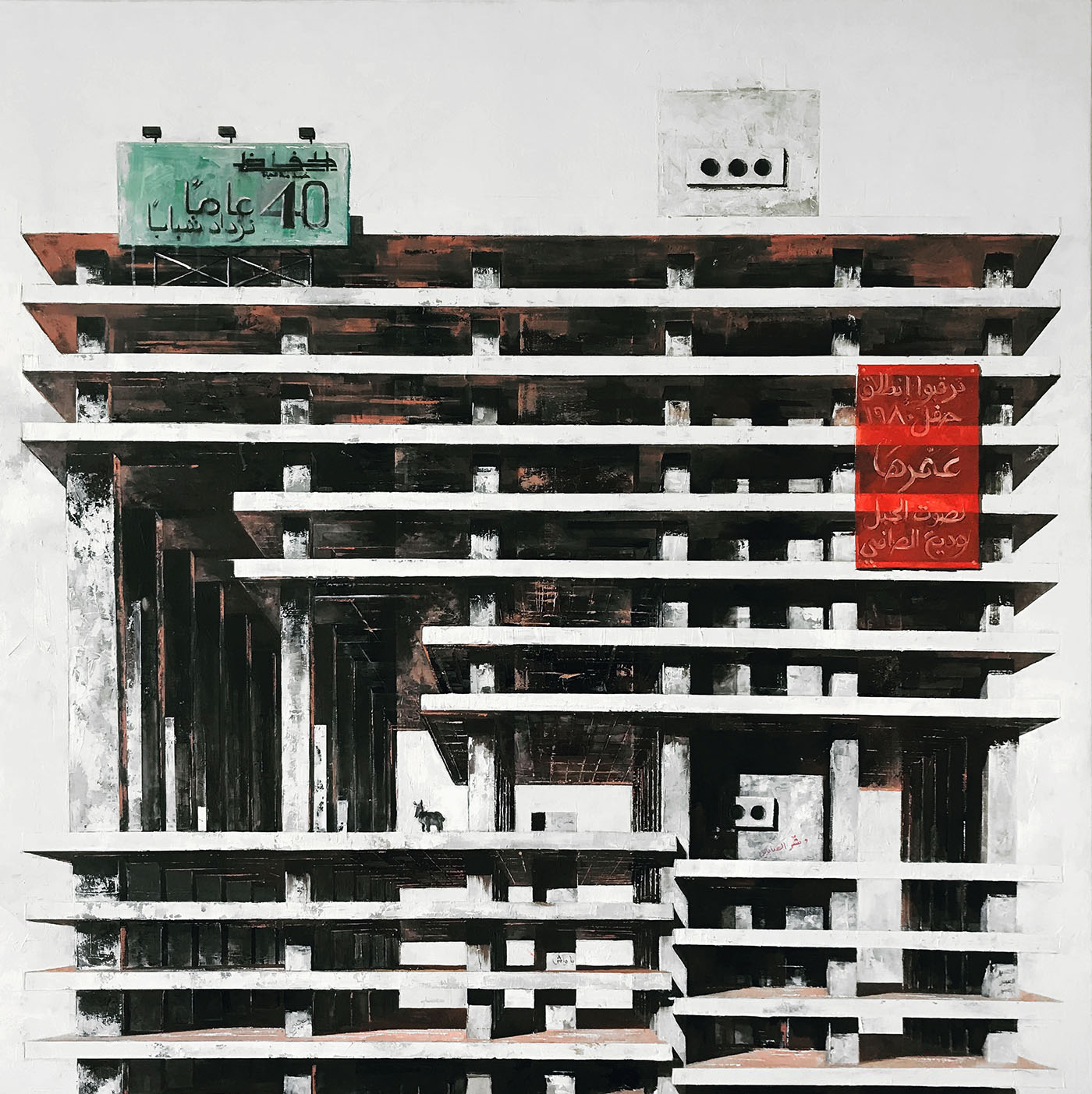

This is why the artist, as he merged into Lebanese society, was keen to recall his Syrian memories, which in medical terms is labeled as “Anamnèse” — memory recall — the title he gave to his 2020 exhibition at Europia gallery in Paris, founded by Syrian couple, Nada Karami and Khaldoun Zreik. Anamnèse retraced a number of symbols of Syrian collective memory, where the exhibits speak for themselves, such as the Hob Hob, the public bus; the Baathist schools; Reign of Six, which represents the Yalbougha complex, a symbol of modernism, said to have been the tallest building in Damascus, the construction of which began in the 1970s but was never completed, reflecting the “stasis” in which Damascus, once the gateway to the Orient, stagnates.

The “stasis” or stagnation has reached Beirut, the artist’s city of choice. The combats are scrawled on the city walls in Syria and Lebanon, through graffiti as “a reminder that the spark of rebellion comes from the people,” as Al Mufti puts it. Thus, the Syrian revolution would be the subject of a solo show in Beirut in 2013, Perspectives of a Revolution in Progress, at Joanna Seikaly Art Gallery. By showing a Syrian prison cell imagined according to the stories told to him by a former Syrian friend who was imprisoned, he revealed the state of abandonment that characterizes both cities, and what this carries with it of “violence, social collapse and separation between social classes.”

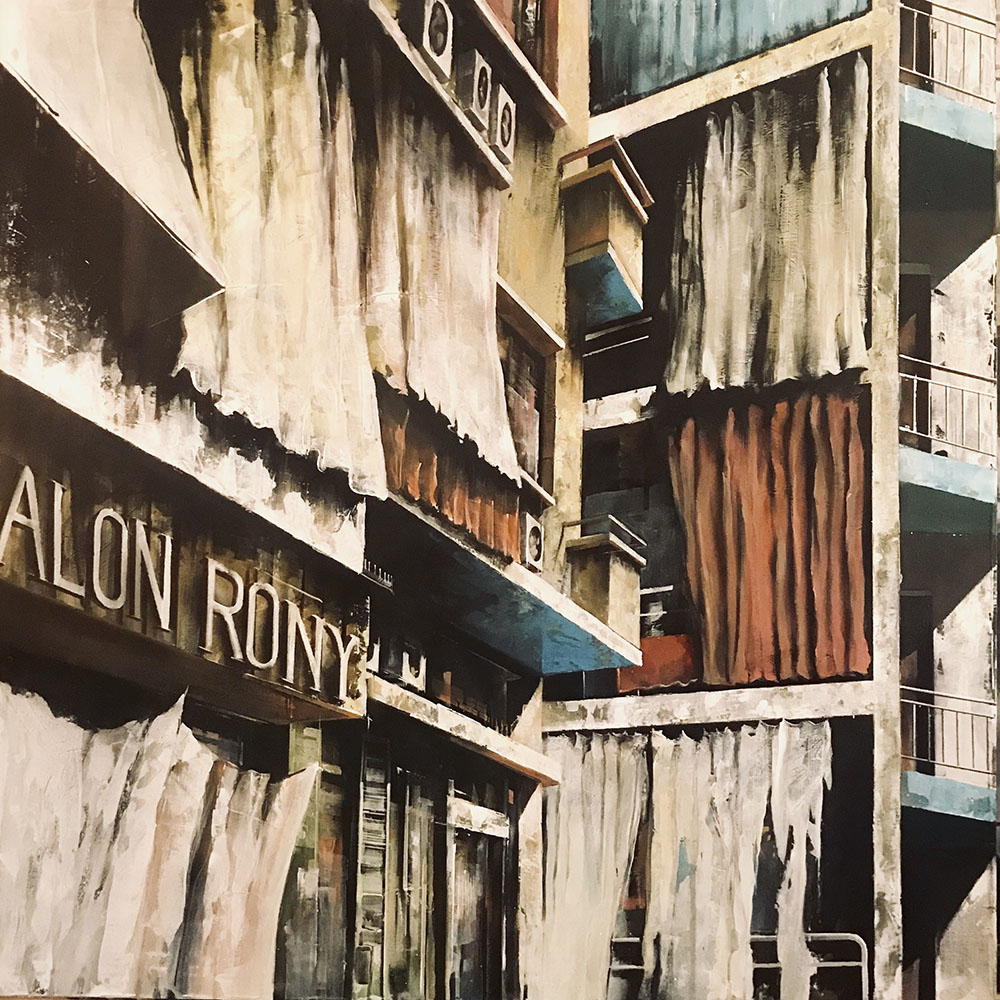

After the Syrian revolution, Al Mufti lived through the Lebanese revolution of October 2019, which also went up in smoke, as did the Lebanese capital devastated by the explosion of August 4, 2020, of which the main thing that will remain are ramshackle, dilapidated façades. These were already showing signs of wear and tear before the explosion, and bore the traces of the dreams and revolts that were stirring in the hearts of the Lebanese people. The same is true of the buildings in Syria, which tell a thousand stories. The urban landscape is eloquent, it accompanies the history of a country; the artist-architect knows how to decipher it and make it speak. By dwelling on it, he aims to be the relay of a time and the custodian of a memory that tends to be quickly erased in the contemporary Arab world. This led to the exhibition And Then Stillness, at Gallery 392 Rmeil 393 in 2020, which was also intended as a visual archive of Beirut since the October Revolution, through the crisis, the social and political collapse. By “stillness,” the artist meant stagnation rather than serenity.

In such circumstances, it was no longer possible for Al Mufti to limit his art to the pure aesthetic exploration of cubism and abstraction, as he had done when living in France. It was no longer possible to turn a blind eye, as does Beirut; this inspired his painting “Hijab in the City.” What he calls “the Lebanese varnish” captures him; he also observes it in the facades of buildings: “There’s something very conservative despite the extravagance in our societies.” Through his art, he seeks to reveal the secret “skin” of Damascene and Beiruti buildings. He uses the word “skin” to refer to facades and walls, which he made speak in an exhibition entitled Urban Scape at Villa Paradiso in Beirut in 2017. Places speak for men.

Mohamed Al Mufti expresses the need “to document the environment both politically and sociologically.” He participates in the life of the city at all levels: painting, teaching and building. For him, the three practices are not only linked, but he also affirms that he needs all three. His teaching is very important to him: a graduate of the École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Versailles, he taught there for a short while before moving to a Parisian architecture school, followed by a return to Syria in 2008, where he also taught. He now teaches at the Académie Libanaise des Beaux-Arts in Lebanon, where he lives. The architect “insists on this balancing between academia and practice, which feed off each other,” including his artistic practice; “art allows me to try and evacuate and experiment things,” he says.

Buildings with a cultural or educational vocation are those that stimulate him in particular, as well as projects with a social dimension. In Syria, he built four public schools. In his native country, where he settled after 15 years in Paris, he was also invited to compete in a project for a mosque in Yaafour, led by Eamar, the famous Emirati public works company. He took the liberty of proposing a project in line with his vision of the world, which is not exactly that of the client: instead of a large mosque, he designed a multi-faith theology center that included a church alongside the mosque, as well as a theology library. The architect points out that he had to delve into the Quran and the Bible to find suras and verses that mention Jesus and Mary, which were incorporated into the project that was obviously not selected. In “the Syria of tomorrow,” Mohamed Al Mufti says he has “imagined buildings that bring people together, not that separate them.” Eamar withdrew with the war and the project was abandoned. For the same reasons, many ongoing projects were interrupted, such as Beit Farhi, a Jewish palace the architect had been commissioned to rehabilitate. For this endeavor, he had sought the help of historians and wanted to trace the actual footprint of the buildings. He had to say farewell to all this, and pack his bags once again, just as he did in the ’90s because of the Gulf War, fleeing Kuwait, where he had grown up, to Syria. In 1994, he left again to pursue his architecture studies in France. This was where he met two of his teachers and mentors whom he highly admires: Jacques Ripault and Michel Rémon, with whom he collaborated. He also founded his own firm, Atelier Mufti Architecture.

He works on diverse projects including social housing and educational buildings, and notably the law faculty in Alençon, Normandy with the commissioned architect Philippe Challes, his friend and colleague. He also participates in international competitions such as Novi BEOGRAD, the extension of Belgrade with Milan Simovic. But the architect explains that, “the changes in public procurement codes in France made it difficult for small and medium size architecture agencies to survive.” Hence, he chose to return to Damascus. In 2017, he took part in the Sketch for Syria Initiative at the Venice Biennale of Architecture, alongside prominent architects (among them Alvaro Siza), who each drew his or her own Syria. “One day I’ll go back to Syria,” says the man who is currently designing and building his own house in the Lebanese mountains, and who is planning a future art exhibition on the theme of aging. Will the wrinkles have already set in by the time he returns to Syria?