Ibrahim Fawzy

“I opened my eyes that first morning in gaol and found no water in the tap, no toothbrush or toothpaste or soap or towel or shower. The toilet was a hole in the ground, minus door and flush, overflowing with sewage, water and cockroaches.” This is how Nawal El Saadawi (1931-2021) delineates the very first day of her imprisonment in the famous Cairo prison, Qanatir, in 1981. El Saadawi soon began writing her book Mudhkirātī fī sijn al-nisāʾ (Memoirs from the Women’s Prison, translated by Marilyn Booth), describing her nightmarish experience in a tomb-like women’s cell along with other female political prisoners and intellectuals, including Latifa al-Zayyat, Amina Rachid, and Awatif AbdulRahman. In her prison memoirs, she documented the incarceration of a large number of female prisoners and their children in a ward with a space equal to that of the ward where 14 women were imprisoned. Stripped of her agency, El Saadawi challenged a powerful despotic regime, such that to resist and survive was an heroic act. The regime couldn’t be easily defeated or changed; withdrawal and passive resistance were the available methods of resistance.

El Saadawi was a heroine behind bars because she managed to resist all types of torture, despite being a woman with a weak constitution. In Memoirs, heroic actions are totally absent, yet the greatest heroism behind high prison walls is to survive, and not to surrender to the jailers’ humiliation. In prison, El Saadawi tried valiantly to continue her political struggle as well as women’s rights activism, and to keep in touch with the world outside.

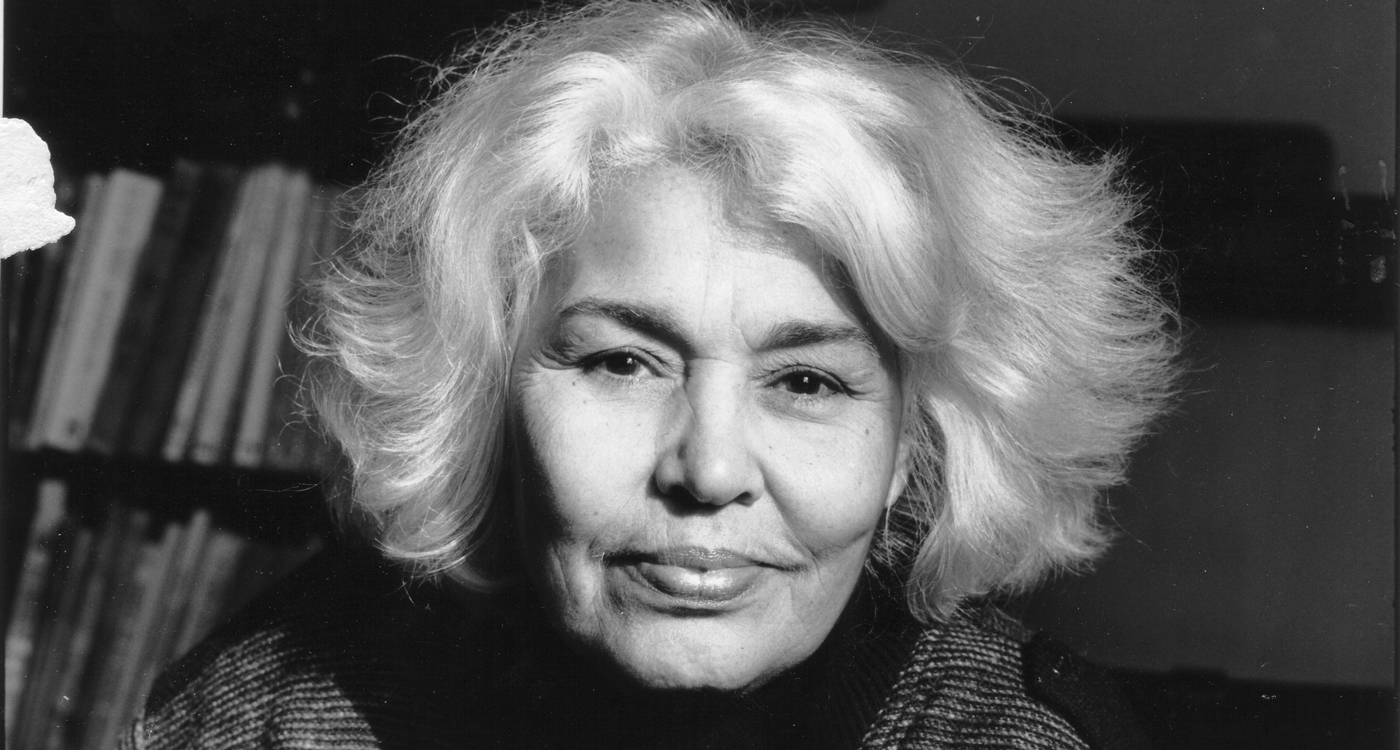

El Saadawi is a renowned Egyptian writer, physician and feminist whose dozens of publications on Egyptian and Arab women have been widely translated into many languages, and have inspired countless women in the feminist movement, both in the Arab world and in western countries. She practiced medicine in Egypt and served as a director general of the Health Education Department of the Ministry of Health in Cairo till her discharge in 1972 because of her outspoken opinions, especially when her first non-fiction book, Al-Mar’ a wa al-Jins (Women and Sex) reappeared after being banned in Egypt for almost two decades because of the feminist arguments it advanced. She established the Arab Women Solidarity Association as well as Noon Magazine, which were forced to close by the Egyptian government in 1991.

Among many other Egyptian intellectuals, El Saadawi was arbitrarily sent to prison for publicly opposing then-President Anwar Sadat’s economic and social policies. She was held in Qanatir until her sentence was fortunately cut short after Sadat’s assassination on October 6, 1981. Unfortunately, her release didn’t bring her safety. In the 1990s, fearing for her life in Cairo, El Saadawi spent three years in exile at Duke University in North Carolina. And in the early 21st century, she faced frequent challenges from the Islamic authorities, who accused her of apostasy. She was a speaker and a visiting professor at various universities in the United States for over two decades, engaging in many public talks about oppression at home. In 2005, she declared that she would stand for the presidential elections against then-President Hosni Mubarak, who had been in power for 24 years at that point. Despite her early withdrawal from elections, her declared intention was to motivate the Egyptians to call for constitutional amendments that allowed for several candidacies for the presidency. In 2011, at the age of 79, she joined demonstrators in Tahrir Square in Cairo, in protests that led to the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak, the latest of her many confrontations with the authorities, both secular and religious.

“In prison, I learned what I had not learned in the College of Medicine. The gecko had crawled over my body and nothing had happened to me. Cockroaches had run over me and nothing had happened,” says El Saadawi. Prison is one of the hardest human experiences; prisoners are primarily punished by losing their freedom. Prison leaves its marks not only on the prisoners’ body but also on their psyche because the authorities and the guards humiliate prisoners, crush their will and devastate their sense of self. However, despite its cruelty, the experience of incarceration changes the prisoners’ vision of life, and gives them the opportunity to develop their abilities of expression, increase their awareness, and historicize their personal experience against political context. Some political prisoners are able to reconstruct their devastated identities through the act of writing, enabling them to regain control over their life after the violations of their human rights in the blinding absence of light — to borrow the title of Taher Ben Jelloun’s fictionalized memoir (tr. Linda Coverdale) — set behind prison walls.

Men have a central position in the history of political prison memoirs, because the tradition of male prison writers has been deeply and widely introduced in literature as well as prison anthologies. Being exuberant and influential, men’s prison memoirs generally concentrate on rebellious images. On the other hand, rebellious images in women’s political prison memoirs are scarce, and relations inside and outside prison walls are highlighted.

Translator Marcia Lynx Qualey postulates that “in the genre of Arab prison writing ـــــ from Egypt, Syria, Iraq, and Morocco ــــــ it is men’s words that are better known.” The reason for the marginalization of women’s political prison memoirs, one assumes, is partially the meagerness of such narratives, the result of the historically small number of female prisoners.

El Saadawi got involved in politics, a supposedly male dominated field. In Memoirs, she wrote, in evocative language and meticulous details, her Kafkaesque first-hand account of her incarceration and resistance to state violence, published four months after her release, in the form of memoir, a male dominated genre as well, to highlight her friendships, mental triumphs, ecstasy, tactics of survival, and the various forces of oppression endured by Arab female prisoners in particular. In the book, El Saadawi manifests the power of control exerted by the government over the citizens, and the consequent confiscation of citizens’ liberties and rights especially their right to express their views. She and her cellmates were deprived of their simplest right as they were sent to prison because they just expressed their views. El Saadawi condemns such an authoritarian regime that puts the fates of thousands of citizens in the hands of one person; people are incarcerated, and released on his orders. The massive arrests, on charges ranging from spying for the Soviet Union to sectarian sedition, carried out by Sadat’s secret service, did not distinguish between right and left, Muslim and Christian, sectarian and secular, or even male and female.

Women’s incarceration experience is somehow different from that of men because of women’s biological features, and gender-based needs. Women are sexually humiliated whether physically or verbally behind high prison walls. Rape, forcing women to use the toilets while being watched by male guards, and forcing pregnant women, on occasion threatened with the destruction of their unborn babies, to give birth, and bring up their babies in the austere environment of prison are destructive weapons used by prison authorities to crush female prisoners’ identities.

Being political, communal, and radical, female political prison memoirs reflect women’s position in patriarchal societies. In his book, Discipline and Punish (translated by Alan Sheridan, 1995), Michel Foucault describes the modern trend toward objectification of the institutionalized female prisoner treated as a flawed object that must be repaired. As for female political prisoners, objectification is intensified because they are already objectified outside prison walls. They are marginalized not only for being prisoners but also for being females. Consequently, in addition to imprisonment and deprivation faced by any political prisoner, women, who are double-marginalized, fight against their stereotypical image imposed by society, and shown clearly inside prisons. Female political prisoners are incarcerated in their stereotypical image imposed by patriarchal societies as well as prisons of the despotic regimes.

The Middle East has witnessed many dictatorships, tyranny, coups, and upheavals. As a result, political prison narratives enjoy a strong presence in Arabic literature as they are exuberant and reflect their authors’ varying backgrounds. Starting with the 1970s, prison literature gained an unprecedented local and international prominence in the Arab world, yet writings about prison experience have gradually been escalated long before that. Literary critic Sabry Hafez locates the genesis of Arabic prison literature in the colonial prison novel, particularly Ihsan Abdel Quddous’s 1957 popular title Fi Baytinā Rağul (A Stranger in Our Home). The late Egyptian novelist and academic, Radwa Ashour, considers political prison narratives “a rich subgenre of modern Arabic literature,” and notes that they “have been produced by both men and women; by liberals, communists and Islamists…who have recorded their prison experience in interviews, oral testimonies and fragments.”

Despite being banned and censored by authorities, numerous narratives of political imprisonment have been published by intellectuals, professional writers and former political prisoners who defied authorities’ attempts to paralyze creativity and portrayed the crisis of freedom in the region in a serious attempt to find a solution to it, and to create a counter-discourse to that of the regimes. In the Arab/Muslim world, political prison literature has blossomed at different moments. Morocco saw this genre grow after two failed coups d’état in 1971 and 1972 respectively, during King Hassan II’s reign, known as “the Lead Years.” Unlike Morocco, where intellectuals and activists were defying an intimate enemy, the situation in Palestine has its own specificity as thousands of Palestinians have experienced political incarceration in their colonial enemy’s jails from 1948 till the present moment. Syria witnessed clashes between the regime of Hafez al-Assad, the Islamic groups and the secular opposition that led to the incarceration of many political prisoners. In a similar vein, political prison narratives in Egypt are ample because a large number of oppositional intellectuals have been subjected to political imprisonment. After the Egyptian revolution in 1952, the country witnessed mass imprisonment of dissidents with two successive military decrees by Gamal Abdel Nasser’s regime: the first decree, in December 1958, ordered the arrest of 169 dissidents, while the second decree, in March 1959, ordered the arrest of 436 dissidents. A couple of decades later, shortly before his assassination, Sadat ordered the biggest roundup of opponents of every stripe. More than 1,600 politicians and writers who opposed his social and economic policies were imprisoned. Most of the detainees, whether during Nasser or Sadat’s regime, were intellectuals who would write accounts of their prison experience. Writers who survived political prison experience in the Arab world, in general, published a considerable number of narratives that unveil the horrific atmosphere inside prisons.

The oppression against women in the Middle Eastern countries has been documented by international human rights organizations, in addition to the textual accounts, narratives, memoirs and autobiographies which ــــ outside of El Saadawi’s Memoirs from the Women’s Prison — are lesser-known. Arab female political prisoners, therefore, managed to construct a new image of courageous women in a patriarchal society, and defied the stereotypical image through getting involved in political activism. Additionally, the act of writing, per se, and the active role of Arab women have contributed to an articulation of a political ideology, transcending the boundaries of gender, race, and ethnicity. The act of writing has also proved that women are capable of being active agents of progress and change. Writing, for El Saadawi, was a means of resistance that helped her document her struggle for survival and maintaining sanity, gain her agency, and prove herself as an active agent in society through a contribution to the field of political prison literature. El Saadawi’s voice meant life while silence meant death, and her powerful writing enabled her to continue her struggle. She wrote to give voice to oppressed and silenced women imprisoned in the wider prison of society. Generally, El Saadawi’s views condemn women’s position in society, and her prison memoir presents Arab female prisoners as oppressed yet resistant.

Writing about prison experience is regarded as the greatest menace to the stability of despotic regimes. El Saadawi narrates that the prison authorities rejected the request for pen and paper, claiming that “it was easier to give a pistol than pen and paper.” Shocked by this line from a farce, El Saadawi writes, “I had not imagined that pen and paper could be more dangerous than pistols in the world of reality and fact.” El Saadawi did not surrender and clandestinely managed to write her diaries on toilet rolls and cigarette papers at midnight while she was sitting on top of the overturned bottom of the jerry can.

Interestingly, El Saadawi exploited the advantages related to her gender as a female prisoner as well as the quite lax surveillance of Qanatir prison. She hid her diaries inside her rollers, packed them in her suitcase, and smuggled them out safely upon her release. El Saadawi undoubtedly was filled with ecstasy and merriment when she hid in a corner to write her secret diaries while others were sleeping. El Saadawi’s feeling of happiness was derived from a temporary sense that her mind was free even if her body was not. Additionally, it might have been derived from overcoming obstacles and creating aesthetic pleasure through accomplishing something meaningful.

From her very first day in prison, El Saadawi decided to live as if she was not going to leave again. Inside prisons, time expands, and space shrinks. El Saadawi narrates the effect of this psychological dimension of time on her:

Time is no longer time. Time and the wall have merged into one. The air is motionless. Nothing moves around me except the cockroaches and rats, as I lie on a thin rubber mattress which gives off the odor of old urine, my empty handbag placed under my head.

Waiting annoyed her and turned meaning into meaninglessness, and time into timelessness. El Saadawi, therefore, attempted to shorten her time through mental journeys, and labor. She got the chance to plant vegetables, and enjoyed digging as well as gardening. Ironically, she found herself free under duress. “I don’t know the secret of that repose or the happiness which came over me all of a sudden,” she writes, “perhaps it was the happiness of self-discovery, when there appears before one’s eyes a new courage or self-confidence of which one was previously unaware, or when one disperses a fear or a phantom with which one has been living.”

El Saadawi narrates how she kept her body and mind sound by doing daily exercise. She could sing a song while taking a shower for the first time since her detention. She depicts experiences that bear resemblance to self-healing. Poetically, she recalls the moments of aesthetic pleasure and reflection including the forceful beat of her heart when she heard the attractive warble of the curlew. She tried to see the curlew, so she jammed her head between two steel bars. Metaphorically, she compares the curlew to “a mother’s voice, like offering a prayer of supplication, like weeping, like a child’s abrupt, long laugh, or like a single scream in the night. Or an uneven sobbing which goes on and on.”

Lyrically, these impressionistic metaphors do not only reflect her yearning for freedom but also mirror her ecstasy. Certainly, prison authority is powerless against the natural desire to have fun. El Saadawi narrates that she experienced the paradoxical feelings of grief and joy behind prison high walls:

In prison I came to know both extremes together. I experienced the height of grief and joy, the peaks of pain and pleasure, the greatest beauty and the most intense ugliness. At certain moments I imagined that I was living a new love story. In prison I found my heart opened to love — how, I don’t know — as if I were back in early adolescence.

She also narrates poetically her emotional response to befriending a young girl: “Happiness, like infection, spreads rapidly. I felt that I, too, had become a child, my heart filled with pleasure. The pains in my back disappeared, and my body felt strong and energetic. I went to the steel-barred door: the dawn breeze massaged my face with invigorating moisture. The sky was still black, but the early light was creeping in slowly.”

In the cramped cell, El Saadawi and her cellmates could carve their small space where they expressed various forms of resistance. Budour (one of the female prisoners), for instance, combed the hair of the Shāwīshah (female guard) so as to know what was happening in prison. Moreover, female prisoners formed an alliance to demand better conditions, and to maintain their sanity in the confines of their narrow cells. El Saadawi also narrates the stories of criminal female prisoners to unveil the socio-economic and political structure of Egypt during Sadat’s era. Fathiyya’s crime, for instance, was murdering her husband who had raped her daughter; Fathiyya and many others were the victims of Egyptian patriarchal society.

An imprisoned political heroine, El Saadawi used her incarceration as a chance to pursue feminist leadership, so she proudly demonstrated solidarity and identified with her outcast companions as much as she did with her fellow political prisoners. Through her survival tactics, El Saadawi triumphed, and documented her experience behind prison walls, revealing that every citizen is a potential prisoner in a police state that comprises walls within walls, creating prisons to guarantee that only the appropriate amount of freedom should seep in. Thus, she dedicates her Memoirs from the Women’s Prison to “all who have hated oppression to the point of death, who have loved freedom to the point of imprisonment, and have rejected falsehood to the point of revolution.”

This is the most powerful essay I’ve read in ages. It moved me so much. What an incredibly courageous woman she was, and her way with language too, in capturing the deepest and most profound.

You have analysed her work beautifully. I really appreciated the quotes you selected and your sensitivity to women’s bodies. I felt like memorising her words.

Your essay made me cry, and inspired me. Thank you so much for this beautiful piece of work. A real and proper tribute to this El Sadaawi.