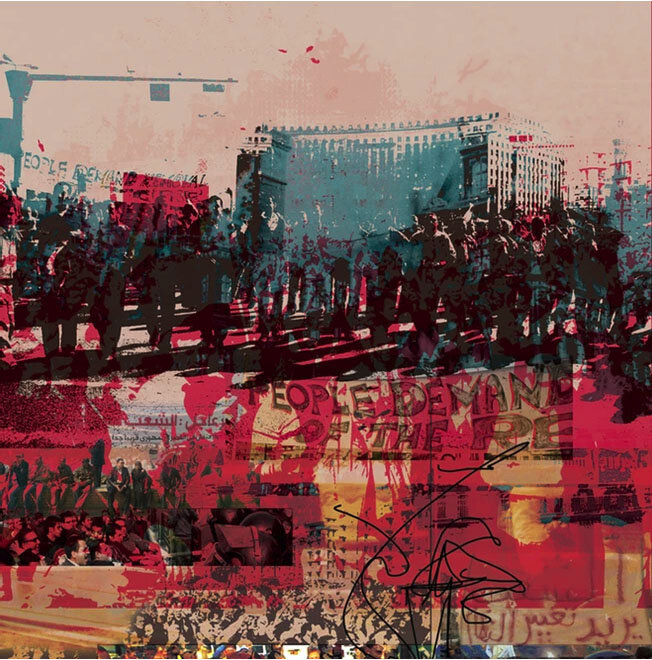

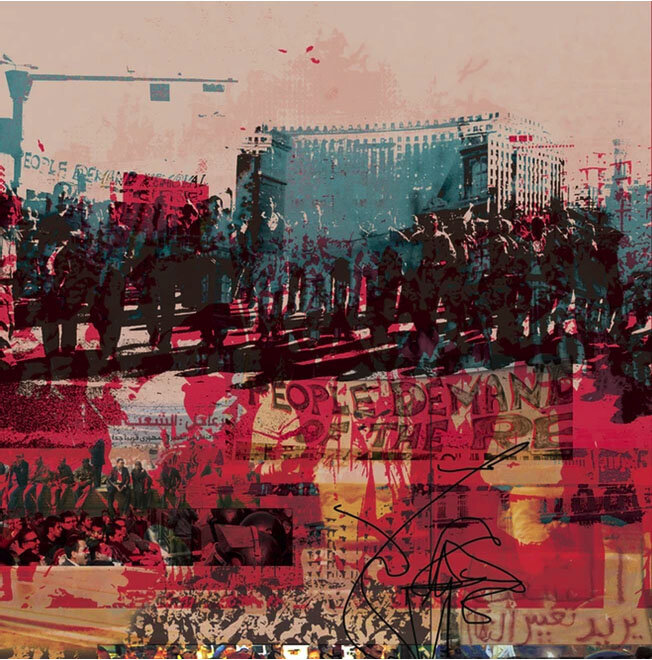

“The Egyptian Revolution,” one in a series by artist Hossam Dirar. <

<

Robert Solé

It is in the middle of winter that the “Arab Spring” comes unexpectedly. On December 17, 2010, in Sidi Bouzid, an agricultural village in central Tunisia, Mohamed Bouazizi, a young unemployed peddler, sets himself on fire after his merchandise is confiscated by police officers. The day after the tragedy, the anger spreads to other cities in the country. President Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, who has been in power for twenty-three years, denounces “terrorist acts” perpetrated by “hooded thugs.” The deaths will soon be counted by the dozens during clashes with the forces of law and order. “Irhal!” (“leave”) becomes the revolution’s byword. Ben Ali is accused not only of having established a police regime, but also of pillaging Tunisia. On January 14, 2011, overwhelmed by the events, he flees with his family to Saudi Arabia.

Five days later, as protests erupted in Jordan, Yemen and Lebanon, and firebombings were reported in Algeria, Egypt and Mauritania, an Arab League summit was convened in Sharm el-Sheikh, South Sinai. For once, its secretary general, Amr Moussa abandons the language of wood. “Arab citizens,” he declares, “are in a state of unprecedented anger and frustration.”

January 25th is Police Day in Egypt. As every year, a handful of opponents want to take this opportunity to “celebrate” the police. A derisory attempt, which has no chance of succeeding. But, this Tuesday, January 25, 2011, encouraged by the fall of Ben Ali, the protesters, who have organized themselves through social networks, will—to their own surprise—drag thousands of Cairo residents in their wake. The protesters clash with the security forces as they try to converge on the huge Tahrir Square (“liberation” in Arabic), which would soon earn its name and become as famous as Tiananmen.

The clashes are not limited to the capital. The balance sheet of this historic day (from now on we will speak of “the revolution of January 25”) is three dead and more than 150 wounded. A live uprising: for eighteen days, the Tahrir event will be filmed and broadcast by television stations around the world.

The “revolution of January 25” has neither leaders nor ideological character. It is not in the name of Marxism, anti-Zionism, or Islam that Egyptians are mobilizing in increasing numbers, but to demand freedom and karama (dignity, respect), to denounce police brutality and corruption. The Muslim Brotherhood, which had been cautiously observing the movement, joins them on the fourth day, taking their large battalions to the streets. It would be the end of Hosni Mubarak, who seemed eternal after twenty-nine years of reign. Even the army, from which he came, eventually drops him. The high military hierarchy thus takes advantage of the situation to remove any chance that Gamal, the pharaoh’s youngest son—a civilian surrounded by businessmen—might one day become president.

On February 11, 2011, the eighteenth day of the Egyptian uprising, Mubarak is forced into exile in his palace in Sharm el-Sheikh. In Tahrir Square, where hundreds of thousands of people have gathered, an immense, interminable clamor greets his departure. Kissing, dancing, crying with joy. Egypt feels itself to become again oum el-donia, the mother of the world.

In North Africa and the Middle East, it is delirium. If the largest Arab country falls into democracy, won’t all the authoritarian regimes, monarchies or republics, fall one after the other, like dominos? Observers see “the end of the Arab exception.” These peoples, who were said to be resigned, show that they are capable of revolting against oppression, like Latin Americans or Eastern Europeans. The region has indeed entered into globalization, giving social networks a new function. “Facebook makes it possible to plan events, Twitter coordinates them, and YouTube communicates them to the world,” explains Egypt’s most famous Internet user, Wael Ghonim.

Map courtesy of Historical Dictionary of the Arab Uprisings by Aomar Boum and Mohamed Daadaoui, in which the authors note: “The initial catalysts of the Arab uprisings were economic deprivation and political repression. The patterns of diffusion were similar across the region in terms of the use of social media as a means for mobilizing and sustaining the pace of the protests.” <

<

Chaos in Libya, horror in Syria

In Tunisia, after Ben Ali’s flight, a government of national unity was formed and a general amnesty decreed. This allows the return to the country of several opposition figures. Free elections are scheduled within six months. In Egypt the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces pledged to ensure a democratic transition. Euphoria continued, although the 18-day uprising left hundreds dead and thousands injured.

But, in this winter 2011, “Spring” does not bloom everywhere. In Manama, the capital of Bahrain, demonstrators belonging mainly to the Shiite community demanded in vain the end of the monarchy and the closure of American bases. Saudi Arabia intervened militarily to quell the rebellion and save the throne of King Hamed ben Issa. It watches like milk over the fire in neighboring Yemen where, on January 27, the forces of order fired on those demanding the departure of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, who has been in office for thirty-two years.

The Arab record is held by Muammar Gaddafi, who came to power in 1969 … Libya also does not escape the contagion. The arrest on February 15 of a Benghazi lawyer, Fathi Terbil, provoked a “day of anger” the next day. And after a violent crackdown, a “National Council” is formed by opponents. Invited by the European Union to respond to the “legitimate aspirations” of his people, the Libyan dictator endeavors to quell the rebellion by all means.

This time, French President Nicolas Sarkozy, who had underestimated the uprising in Tunisia, took the lead: after recognizing the Libyan National Council as the sole legitimate political authority, he persuaded London and Washington to intervene militarily. On March 17, 2011, the UN Security Council authorized the use of force, while Benghazi, a stronghold of the insurgents, was threatened with aerial bombardments.

From then on, Gaddafi will not stop losing ground. On October 20, he tries to flee the city of Sirte, when his convoy is attacked by NATO planes. He finds refuge in a tunnel with his bodyguards, before being lynched by insurgents. His death was immediately followed by clashes between militias, who fought for control of local territories or various traffic routes. Libya then appears for what it is: not a real state, but an aggregation of tribes. The chaos that reigns there risks destabilizing neighboring countries. Already, trucks filled with assault rifles, machine guns and rocket launchers, seized from government forces, were leaving for Mali, Chad, Sudan, Niger, Tunisia or Egypt.

It is however Syria that will experience the bloodiest “Spring”. On March 13, 2011, fifteen teenagers are arrested in Deraa, a southwestern city with a Sunni majority. Their transfer to a prison in the capital and the abuses they suffered there revolted the local population. The Ba’ath Party headquarters and the courthouse were burned down. Deraa is occupied by the army, while the rebellion spreads and becomes more radical. In Damascus, Aleppo and Homs, thousands of protesters clash with security forces firing live ammunition.

Unlike Tunisia, Egypt and Libya, where all Muslims are Sunni, Syria is ruled by an Alawite minority, descended from Shi’ism. The “Spring” there very quickly took the form of an inter-religious conflict. The “Fridays of anger” follow one another, at the exit of the mosques, after the great weekly prayer. The repression is terrible. Three thousand soldiers, accompanied by T-55 tanks, entered Deraa on April 25. Protesters are executed in the stadium and the wounded are taken to hospital.

The Free Syrian Army is collaborating with Kurdish forces in the north of the country. But it is soon supplanted by several Sunni Islamist groups, including the al-Nusra Front, a branch of al-Qaeda. These groups are aided by Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar, while the Syrian regime receives support from Iran and various militias that are subordinate to it, starting with the Lebanese Hezbollah.

French president François Hollande, who succeeded Nicolas Sarkozy, supports the Syrian opposition. His Minister of Foreign Affairs, Laurent Fabius, calls Assad an “assassin.” In the summer of 2013, France is about to intervene militarily with Great Britain and the United States after a government chemical attack in Ghouta, in the suburbs of Damascus that caused the death of several hundred people. But Paris is let down by London and Washington. Russia then enters the scene and, very skillfully, occupies the center of the diplomatic game. While continuing to strongly support Bashar al-Assad, it proposes to place the Syrian chemical arsenal under international surveillance, before its destruction. On the 27th of September, 2013, the UN Security Council passed a resolution to this effect. Assad is saved. He could not have fared any better.

Activist and graffiti artist Ammar Abo Bakr created a mural in Mohamed Mahmoud Street in Cairo depicting martyrs who were tortured and killed by security forces <

<

An Islamist parenthesis

While Syria is being torn apart in blood, democratic advances are being made in several countries. In Tunisia, after free elections, Moncef Marzouki becomes President of the Republic in December 2011, while Hamadi Jebali, the number two of the Islamist party Ennahdha, winner of the legislative elections, holds the post of Prime Minister. In Egypt the public trial of Hosni Mubarak opens, along with his two sons and several dignitaries of the deposed regime. This has never before been seen in the Arab world! The various elections are won by the Islamists, the only opposition forces organized in the Nile Valley. In order not to insult the “Spring,” some irregularities in the elections are ignored. Mohamed Morsi, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood, is narrowly elected President of the Republic in June 2012. For the first time since the fall of the monarchy sixty years earlier, the head of state is not from the army, and he is an Islamist.

In the Arab world, people talk about “contagion” and “dominoes” again, but in the opposite direction: if Egypt falls into Islamism, won’t all countries follow one after the other? The Muslim Brotherhood has put away its old slogan (“The Koran is the solution”), but the Brotherhood’s incompetence and greed worry many Egyptians who are ready to “give them a chance.” As for the military hierarchy, it cannot stand the existence of a competing force encroaching on its prerogatives and threatening its empire. In June 2013, millions of citizens who fear the establishment of a religious state take to the streets with the support of the military. The army hastens to depose Mohamed Morsi and put him in prison. This is the second time in two and a half years that a head of state is overturned.

The bloody repression of an Islamist rally in Cairo soon taints what appeared to be a “new revolution.” It is now clear that power belongs to the army. Because he has neutralized the Muslim Brotherhood, Marshal Abdel Fattah al-Sissi will have in May 2014 an election … of marshal to the presidency of the Republic. He will nevertheless be confronted with attacks, a worrisome jihadist guerrilla war in the Sinai and a very worrisome economic situation.

Events in Egypt have prompted the Tunisian Muslim Brotherhood to be cautious. They have decided not to present a candidate for the presidential election of December 2014, which is won by Béji Caïd Essebsi (88 years old), leader of the Nidaa Tounès party. This will not prevent them from being associated with power. The Nobel Peace Prize 2015 will be awarded to four institutions that have worked for this peaceful transition: the Tunisian League for the Defense of Human Rights, the National Bar Association, the main workers’ union and the employers’ union.

Above all, destroy Daesh

With the fall of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, Palestinian Hamas lost one of its most valuable supporters. Yet it is being dragged into a disastrous war against Israel in July-August 2014. Ten days of air raids followed by a ground offensive results in thousands of victims and considerable damage in Gaza. This open-air prison comes out bloodless from the conflict, despite the “victory” claimed by Hamas.

The despair of the Palestinians, convinced that they will never have a state, is then expressed by the “intifada of knives.” In seven months, more than 350 knife attacks are committed against Israelis in the West Bank. They result in 34 victims, but also some 200 deaths on the side of the assailants, usually killed by police officers.

If the democratic advances of the Spring had been a disavowal for the jihadists, adepts of violence to conquer power, the winter in which part of the Arab world is sinking plays in favor of their theses. All attention is now focused on Daesh (acronym for the Islamic state in Iraq and the Levant) whose leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, has proclaimed himself Caliph. This competitor of al-Qaeda not only controls a vast territory straddling Iraq and Syria and imposes a medieval way of life, but also organizes or incites murderous attacks in the countries that fight it. This is the case of France, which has been bereaved several times, as well as Tunisia: the attacks committed in 2015, at the Bardo Museum and then in a seaside resort near Sousse, diverted tourists and considerably affected its economy.

Westerners are determined to destroy the Islamic state, even if it means serving Bashar al-Assad. The Syrian conflict becomes illegible. While Russia provides the regime with direct military support by indiscriminately bombing all its adversaries, the United States and its allies attack Daesh and actively support the reconquest of Mosul by Iraqi troops and Kurdish fighters from October 17, 2016. One year later, it was the fall of Raqqa, in Syria, whose self-proclaimed caliph had made his capital. Baghdadi will be killed on October 27, 2019 during an operation by American special forces.

MBS does a lot of damage

No “Spring” in Saudi Arabia, but the entry on the scene of a modern young man, appointed Minister of Defense in 2015: Mohamed ben Salman, known as MBS, son of King Salman, is another figurehead of a sovereign. He is said to intend to reform this society from another time—he will, for example, allow women to drive—but he will do great damage.

MBS is dragging several countries in the region, including the United Arab Emirates and Egypt, into a war against Houthi rebels who have seized vast areas of western and northern Yemen, including the capital, Sana’a. The Houthis, a branch of Shi’ism, are backed by Iran, Saudi Arabia’s absolute enemy. Not only did they resist, but the anti-Houthist front broke up, and separatists conquered Aden, the great southern port. The dead numbers in the tens of thousands. The UN denounces “the worst humanitarian crisis in the world.”

On November 3, 2017, MBS summons Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri to Riyadh, accused of not being firm enough with Iran. He forces him to resign and holds him prisoner. The affair causes a scandal. Hariri returns to his post in Beirut, to great acclaim, after an intervention by France. The same month, the Crown Prince has some 200 Saudi personalities locked up at the Ritz-Carlton in Riyadh as part of an anti-corruption operation. They are released only in exchange for the payment of large sums of money to the Treasury. Last but not least, in October 2018, MBS brutally murders an exiled journalist, Jamal Khashoggi, inside the Saudi consulate in Ankara. This provokes a great deal of emotion in the world. The prince, however, seems immovable, thanks to the support of his father and President Donald Trump, partners in their struggle against Iran.

The activism of two non-Arab countries

Three former empires—the Persian, Russian and Ottoman—sometimes allies, but always competitors, are very active in this shattered Arab world. Each one plays its own score, with different objectives.

Iran continues to support Bashar al-Assad. The Syrian dictator also benefits from Russia’s military entry into the conflict from September 2015. This support will translate into decisive victories against the rebel movements in Aleppo (December 2016), Homs (May 2017) and Deraa (July 2018).

Assad managed to stay in power, but at what price? Having become beholden to Tehran and Moscow, he reigns over a devastated country. This terrible conflict has left some 380,000 dead, countless wounded and led half of the Syrian population to migrate or go into exile.

Another non-Arab actor, Turkey, contributes to strongly disrupt what remains of the “Spring”. Turning his back on the West and posing as the Caliph of Sunni Islam, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan pushes his pawns in all directions, whether directly or through mercenaries. His country is home to three million Syrian refugees. He uses them as a threat to Europeans who fear a migratory upsurge.

On October 9, 2019, in favor of an American withdrawal, Turkey launches an offen

sive against Kurdish forces in northern Syria. This operation allows it to occupy, at its border, a strip of territory 120 kilometers by 30.

Erdoğan is also active in Libya, with a dual purpose: to exploit gas in the Eastern Mediterranean and to intensify its blackmail of migrants by controlling another refugee route to Europe. Indeed, many Africans transit through this country in full chaos, often in terrible conditions, and then try to reach Europe by sea.

Libya is almost cut in two, between a Tripolitan (west) administered by the Tripoli government and a Cyrenaica (east) under the dissident Marshal Khalifa Haftar, who is accumulating victories on the ground. In December 2019, Erdoğan signs a maritime demarcation agreement and a military cooperation pact with the Tripolitan authorities. Thousands of pro-Turkey Syrian mercenaries, supported by armed drones, will reverse the situation. But the Russian air force intervenes to rescue Haftar: in this shattered country, Tripolitania is “Turkified” and Cyrenaica is “Russified” …

The Tunisian exception

Nine years after the beginning of what we no longer dare to call “Spring”, the Arab world appears in a sad state. If, on the whole, the monarchies are doing better than the republics, their old rivalry from the time of Nasser and the Ba’ath Party has been supplanted by numerous internal wars: between Sunnis and Shiites, military and Islamists, Hamas and the Palestinian Authority, Saudi Arabia and Qatar … not to mention the Arab-Israeli conflict which, in this field of ruins, turns to the advantage of the Jewish state. Donald Trump recognized on December 6, 2017 Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, which will see its relations normalized with the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Sudan and Morocco. The Palestinian cause no longer seems to interest many people.

In Egypt, contrary to what happens in Syria, Libya, Iraq or Yemen, the state maintains itself. But the “Spring” of 2011 is only a memory. The government fiercely represses the slightest protest. The army now intervenes in all the activities of the country, to the great displeasure of industrialists and businessmen. The horse’s remedy inflicted on the economy to reduce the deficit has accentuated inequalities. Galloping demographics—the population has doubled in thirty years—amplifies unemployment and leads to a deterioration of public services (health, education, housing). In the north of Sinai, the government has not succeeded in eliminating jihadist movements, despite the deployment of significant military resources and discreet aid from Israel.

Tunisia, the first country to rise up, appears to be the only survivor of the Arab Spring. It continues its democratization and freely elects its leaders, but is experiencing great economic difficulties. The number of Tunisians seeking to emigrate to Europe continues to grow. Disillusionment and despair manifest themselves in various ways, including suicide. On a wall in Sidi Bouzid, not far from the place where Mohamed Bouazizi set himself on fire, the word “revolution” (ثورة ) has been tagged upside down.

Aftershocks of an earthquake

Would the Arab Spring, that earthquake that took everyone by surprise, have been just a quick digression closed back up upon itself? Unexpected aftershocks will revive the hopes of the Democrats. In Baghdad, thousands of demonstrators will occupy Tahrir Square in November 2019 to call for the “fall of the regime” of Iraq, which was drowned by Iran. Blood is also running in other cities of the country. But it is above all Sudan, Algeria and Lebanon that are attracting attention.

In Sudan, the movement is triggered by the tripling of the price of bread. A first demonstration, organized on December 19, 2018 in the working-class agglomeration of Atbara, immediately spilled oil. A coalition of opponents, supported by trade unions and lawyers, demands the departure of Omar al-Bashir, the general who had seized power in 1989 with the support of Islamists. The population is suffering from the violence and vexation inflicted on it by the security services, but also from an economic crisis that has lasted for years. The crushing of a rebellion in Darfur is followed in 2011 by the partition of the country: South Sudan took with it three quarters of the oil production.

Despite the repression, a huge sit-in is organized in Khartoum in front of the headquarters of the armed forces. It is to last several months. A 23-year-old student, Alaa Salah, who climbed onto the roof of a car to sing a song against the dictatorship, became an icon of the movement, revealing the vitality of this civil society and the place of women in it.

Skillfully, the protesters encourage the army to fraternize with them. On April 11, 2019, the dictator is placed under house arrest and removed from office. A transitional government, involving civilians and the military, forms under the leadership of a respected economist, Abdallah Hamdok. The conditions seem to be in place to lift sanctions against Sudan, which has so far been accused of supporting terrorism, even though its political future remains uncertain.

In Algeria, in order to prevent an uprising, the government counted both on the easing of social tensions thanks to its oil revenues and on the trauma left by the bloody civil war of the 1990s. But by early 2019, the coffers were empty due to the fall in the price of black gold.

On February 22, as Abdelaziz Bouteflika is seeking a fifth presidential term despite the stroke that rendered him impotent, anonymous calls on social networks encourage demonstrations in Algiers, Constantine, Oran and Sidi Bel Abbès. The Hirak (“movement” in Arabic) is born and the government will not stop hearing about it. Every Friday, citizens of all ages, from all walks of life, invade the streets, carrying the national flag in a cape or scarf. A gigantic concert of pots and pans is addressed to the “system”—and not only to the puppet president—that they want to get rid of.

The huge Friday crowds have the intelligence to refuse all violence: to guns and truncheons, they respond with the infinitely repeated slogan “Selmeya” (pacifism). On April 2nd, Bouteflika resigns, after being released by General Ahmed Gaïd Salah, Chief of Staff of the Army. This quasi-octogenarian poses as a reformer, whereas he embodies—along with the FLN and the business clans—one of the pillars of the system that has been repudiated. His rivals are arrested, and a new presidential election is organized. But the five candidates all come from the ruling party. On December 12, 2019, the election of Abdelmadjid Tebboune, 74 years old, deceives no one. And only 23% of Algerians will vote in the constitutional referendum of November 1, 2020. Meanwhile, the epidemic of Covid-19 will have interrupted the Hirak. This movement is suffering from what was undoubtedly one of its strengths: the voluntary absence of leadership. Nine years earlier, the same could be said of the Egyptian revolutionaries.

IS Beirut EXPLODING?

Demonstrators in Beirut protest government policy on easing the economic crisis, 22 October 2019 [Photo: Mahmut Geldi/Anadolu Agency]![Demonstrators in Beirut protest government policy on easing the economic crisis, 22 October 2019 [Photo: Mahmut Geldi/Anadolu Agency]](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/beirutoct2919protests.jpg) <

<

In Lebanon, too, an uprising without leaders has emerged from a seemingly derisory event: the imposition of a new tax on the use of WhatsApp. On October 17, 2019, the streets of Beirut are invaded by an angry mob that attacks the political leaders. The national currency devalued sharply over the summer, causing prices to soar. This is the result of accounting acrobatics that the Bank of Lebanon has been performing for years in order to finance the budget deficit and to maintain the parity of the pound with the dollar: a sort of Ponzi pyramid consisting in sucking foreign currency deposits from commercial banks at fantastic interest rates. These schemes have greatly enriched the shareholders of these institutions, including political leaders. Until the day the “pyramid” began to collapse…

The economic crisis is hitting hard not only the poor—including a million Syrian refugees—but also the middle class. Families can no longer afford to pay for their children’s schooling in the country’s many private schools. Restaurants are even seeing some of their regular customers ordering half-servings…

But the tens of thousands of people, Christian and Muslim, who demonstrate every week in the country’s main cities are demanding more than just economic measures: the departure of an often highly corrupt political class that has clung to power since the end of the civil war of 1975-1990. The confessional system now appears to be a disastrous clanism, allowing—a unique case in the world—Muslims and Christians to govern together. Even the Shiites are blaming Hezbollah, which is rightly described as a “state within a non-state.”

On August 4, 2020, when Covid-19 was added to the economic crisis, a tremendous explosion shakes the city of Beirut, ravaging the eastern districts in a matter of seconds, killing 190 people and injuring countless others. Negligence, carelessness, corruption? It is discovered that 2,750 tons of ammonium nitrate had been stored for six years in warehouses in the port. Anger is mixed with despair. Many Lebanese, ruined and exhausted, see only one solution: exile.

But in Lebanon, as in Algeria or Sudan, the game is not over. The same can be said of all the countries that have experienced a “Spring”, however fleeting, followed by a counter-revolution. The Arab peoples now know that it is not enough to overthrow an authoritarian regime to achieve democracy. Elsewhere in the world, the road has always been long and painful. Refusing to despair, the most committed or lucid citizens are trying, in Gramsci’s words, to combine the pessimism of intelligence with the optimism of will.

<

Robert Solé’s “Ten Years of Hope and Blood” originally appeared in N°328 of France’s 1 weekly devoted to The Arab Spring: Confiscated Revolution on Jan. 6, 2021 and appears here by special arrangement, translated by Jordan Elgrably.

Each Wednesday, 1 weekly focuses on a single current topic and explores it through several eyes. Readers of French will find new ideas and widely-ranging opinions and contributors you won’t read elsewhere. TMR readers can benefit from access to 1’s digital weekly edition with a special subscription offered at just 1€/month. Click here for the offer.