Gazan artist Malak Mattar transmutes the many images of this livestreamed genocide saturating newsfeeds and timelines, televisions, hand-held devices and screens the world over into an arresting documentary work. “I don’t want to forget,” she told me. “We will never forgive, and we will never forget.” New work in The Horse Fell Off the Poem, April 16-June 14 at the Feruzzi Gallery in Dorsoduro, Venice.

Nadine Nour el Din

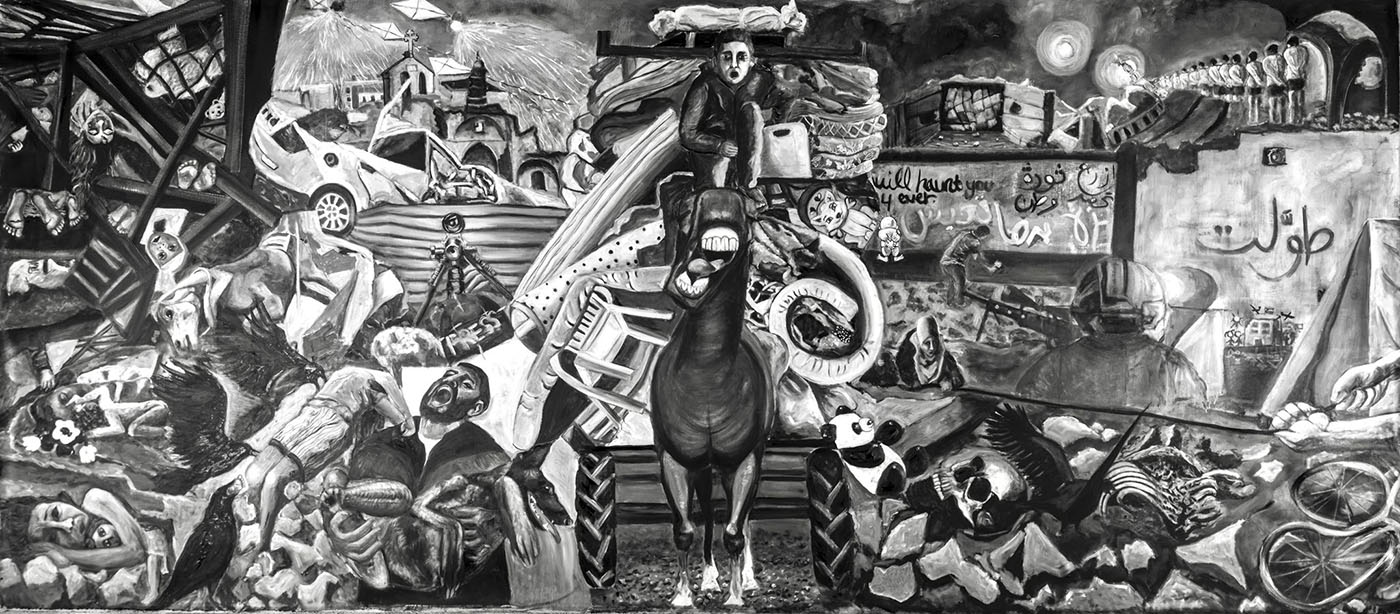

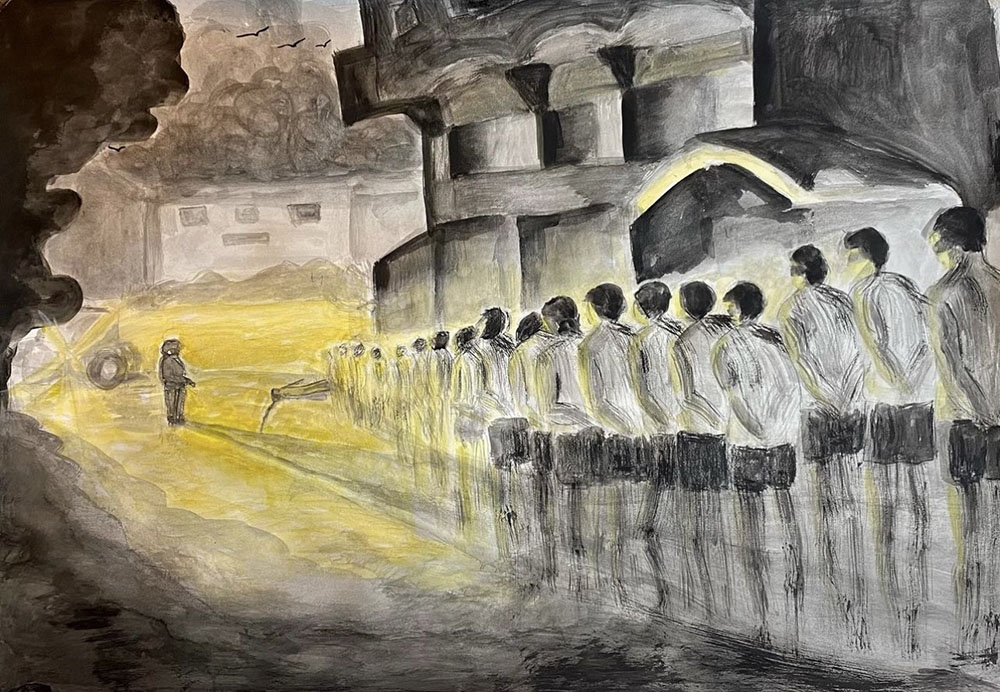

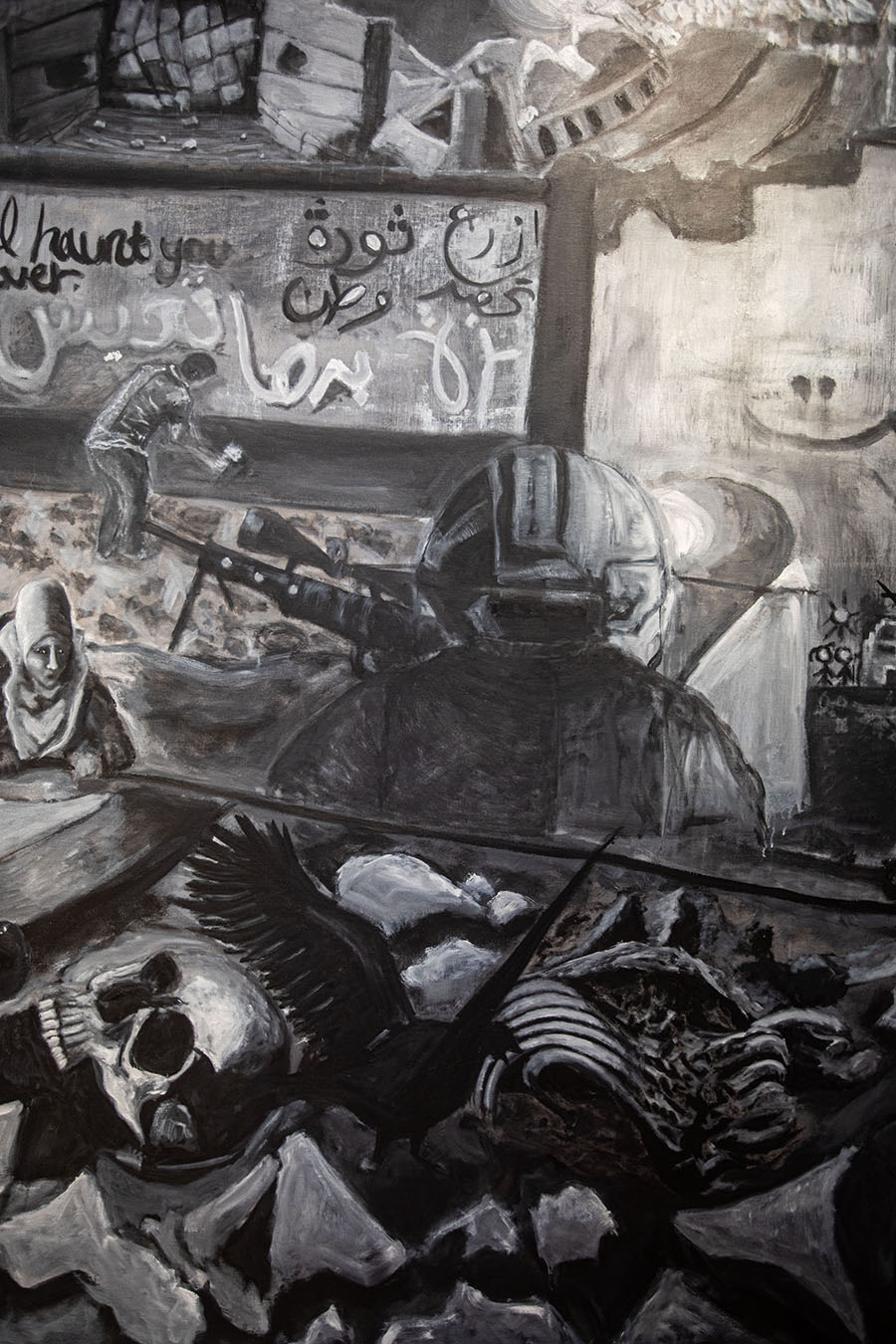

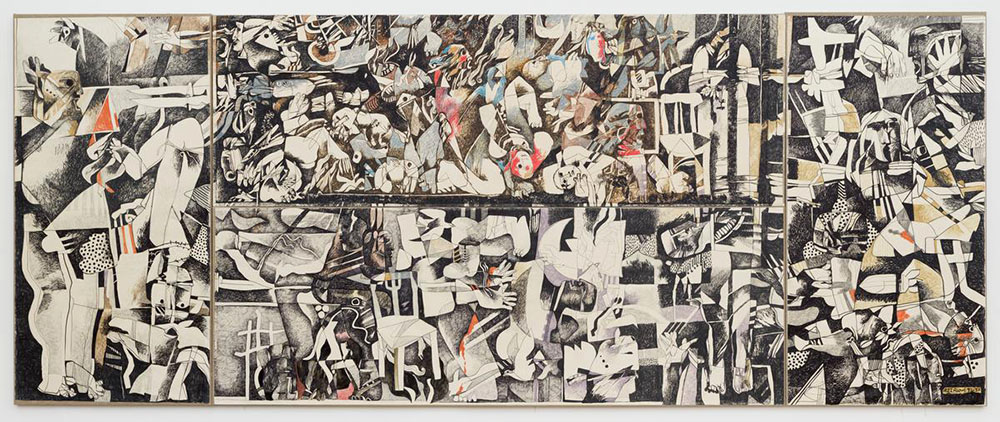

At the center of a larger-than-life monochromatic painting, a horse cries out in anguish. He is being driven by a frightened young boy with his belongings piled on the cart behind him. Part of these closely-guarded belongings include a deceased body, shrouded in white. Scenes of death and destruction surround them, layered in fragments across the entire breadth of the canvas, forming pieces of a painful puzzle too difficult to take in and process all at once. A harrowing tableau of just some of the abominations we’ve seen come out of the genocide in Gaza: bodies crushed under the rubble; a wailing man carrying a wounded dog; children’s lifeless corpses; decomposing human remains; children’s stuffed toys left behind in the ruins; a row of stripped-down Palestinian men; a rain of white phosphorous bombs; pulverized architecture; a camera and an abandoned press vest; crushed cars; birds feeding on human remains. A young man sprays graffiti on a wall. An English fragment reads: “will haunt you forever.” In Arabic: “Gaza wants to live,” and, “plant a revolution, sow a nation.” Titled No Words, this breath-taking painting by Palestinian artist Malak Mattar is at once captivating and deeply unsettling.

Known for her bright and colorful paintings, Mattar’s recent body of work is dark and devoid of color. A survivor of numerous Israeli assaults on Gaza, Mattar recently completed an artist residency in London with An Effort, a non-profit organization that supports residencies for women artists from the Arab region. She used her time there to document the loss and horror unfolding at home from what she terms “a humanitarian perspective.” Her visceral paintings are evocative recreations of real-life horrors: the womb of a dead woman and her dead unborn child; portraits of children killed by Israeli airstrikes, and a group of premature babies, abandoned and alone in the world. One of her most compelling works, rendered in charcoal on paper is entitled May the birds who have eaten our flesh crash in your window. It depicts a flock of birds flying against a dark sky, and was inspired by children’s testimonies about the birds they saw eating the flesh of dead bodies.

Considered a rising young Palestinian talent, Mattar (b.1999) is largely self-taught, having never formally studied art prior to her enrollment at Central Saint Martins, where she is presently working toward an MFA in Fine Art. She comes from a family of poets and artists, and it was in fact in the studio of her uncle Mohammed Musallam where she first picked up a paintbrush as a child.

After some delays, Mattar arrived in London to begin her course on October 6, 2023, just as her world would change with the Israeli assault on Gaza. She found herself far from home, worried for the safety of her family as she watched her hope to return diminish. Initially unable to paint or draw, Mattar broke through the sense of paralysis brought on by the events following October 7th, by sketching and painting gesturally the many images she was seeing from Gaza. I visited her studio several times over the course of her residency, and saw her body of work develop. She cites her mediums as “tears, telegram, charcoal, ink, and paint,” explaining how emotional the process has been for her. She describes a sense of urgency to document the scenes that she has been witnessing, and a responsibility to memorialize them so that people do not forget.

As Jehad Abusalim writes in his foreword to Light in Gaza: Writing Born in Fire (Haymarket Books 2022) — the cover of which is illustrated by Mattar — “because Gaza’s experience is unique, the place, the people who live there and their story become abstract and challenging to explain to an outsider who has never been to Gaza or lived there enough to absorb aspects of its experience.” And the crucial aspect of Mattar’s work lies precisely in its ability to resist such obscuration, in its refusal to submit to the erasure of context. Gaza’s destruction, the oppression of its people are all presented through the unique gaze of a Gaza native.

Her work began as loose, gestural sketches in charcoal and pencil, drawn from the constant stream of documentary images coming out of Gaza: horrific scenes of carnage, destruction and massacres. Over the course of her residency, all these sketches and smaller paintings became studies that informed her monumental canvas. Within the landscape of devastating loss and destruction, Mattar painted her own hands pulling a woman out from under the rubble. The work reads as an attempt to overcome her sense of helplessness, an embodiment of her desire to act through her work. The result of a deeply personal and emotive process, Mattar worked through long stretches of time in which communication blackouts prevented her from being able to contact her family as they were displaced from their home and separated from one another.

For Mattar, the experience of displacement is the most significant aspect of this genocide, which she describes as worse than the Nakba of 1948. “Personally, I feel that this is worse. Maybe ‘48 was more traumatizing, but the scale, advanced military, documentation, and social media make this the most documented ethnic cleansing.”

Once bold and teeming with color, her works are rendered in black and white. Mattar credits this shift to black and white to her loss of hope, explaining that she “simply did not see the colors.” For Mattar, color represented a sense of celebration, beauty and innocence even in the worst moments, perhaps most evident in her series entitled You and I, which she painted during her traumatic experience of the Israeli assault on Gaza in 2021. Through this new body of work, however, a profound sense of grief informs her approach. “I relinquish my role of giving hope to people,” she explains. Her use of this monochromatic palette recalls the colonial documentation of Palestine in early photographs, all recorded from an imperialist gaze. Mattar appropriates that same palette to assert a Palestinian perspective, and what’s more, an unapologetically subjective and personal one.

Even as I saw her painting in its early stages, I could tell that Mattar was making historic work — both in her urgent documentation of the tragic events unfolding in Gaza and in the mature visual language that she had developed to do so. Details of her developing work conjured images of other works: renowned Iraqi artist Dia Azzawi’s monumental Sabra and Shatila Massacre (1982-3) and pioneering Palestinian artist Samia Halaby’s Drawing the Kafr Qasem Massacre of 1956 (1999-2012), which, in addition to sharing a largely monochromatic palette, also document atrocities committed by Israel in haunting detail. Azzawi was moved to depict scenes of the massacre after reading Quatre Heures à Chatila (Four Hours in Shatila) by French writer Jean Genet, who wrote, “a photograph doesn’t show the flies nor the thick white smell of death. Neither does it show how you must jump over the bodies as you walk along from one corpse to the next… A barbaric party had taken place there.” For her part, Halaby created her series of drawings to reconstruct the massacre of 1956, in an attempt to recreate what photography might have documented. She based her images on interviews with primary sources including survivors and victims’ families, creating visual evidence where there was none.

Mattar on the other hand, transmutes the many images of this livestreamed genocide that is saturating newsfeeds and timelines, televisions, hand-held devices, and screens the world over, into an arresting documentary work. “I don’t want to forget,” she told me. “We will never forgive, and we will never forget.”

Countering the image fatigue that doomscrolling through images and footage on social media, or seeing them in the news produces, the power that documentation through the medium of painting holds, lies in its ability to compel you to see the scene in its entirety, as well as drawing you in to focus on its meticulous details, bringing together recognizable characters and events that have come to form a collective consciousness of the past several months of genocide. Here, painting animates the deeply personal and political subjects in a way that activates multiple sensory experiences, producing works of explicitly subjective witnessing, memorializing these characters and events beyond mere documentation.

Unintimidated by the scale of the canvas, the largest she has painted, and far outsizing the artist herself, Mattar was determined to use the privilege of her safety and vantage point away from Gaza to paint a more truthful, more complete picture of the ongoing atrocities, despite how well-documented they are. Painting No Words was far from being a cathartic experience, but all the while she worked, she thought of home, of her family and friends, and her aunt who was killed. A painful communion with home, but a powerful one nonetheless.

Why did she make the image of the horse so central to No Words? She explains that there is a “culture of horses in Gaza,” that, growing up there, the animals were always relied on as a safe medium of transportation. “Throughout all the assaults,” she tells me, “culture has always been at the heart of the damage.” And so for Mattar, the animal’s expression of horror has a twofold power, at once conveying exactly that — wordless animal horror — and at the same time depicting this erasure of specifically Gazan culture. Other such elements of the painting include the Rashad Shawa Cultural Center which she witnessed being built growing up, the Great Omari Mosque, where she remembers socializing on Fridays, Al-Shifa Hospital, and the Church of Saint Porphyrius. She paints the personal within this political collective memory, most evident in details such as the white garden chair, which represent her own memories of gatherings with her grandparents.

Mattar’s residency culminated in a London exhibition entitled Last Breath, which was on display at Cromwell Place from March 6-10, 2024. Speaking at the opening of her exhibition, she described the centerpiece of her exhibition, the monumental work produced during her residency as a “documentation of the most barbaric and most horrific genocide in our century by the Israeli occupation. When I think of this,” she added, “it didn’t really start in 2023. It triggered so many memories of my life as a war survivor since the age of eight. This painting unfolds so many of the memories I had as a child. This painting is a reminder that we have failed… This is not only my painting, it belongs to the people of Gaza, and I hope it really disturbs you, I hope it haunts you forever… You’re all complicit, I’m sorry. The fact that you’re living a normal life, I’m so angry at this.”

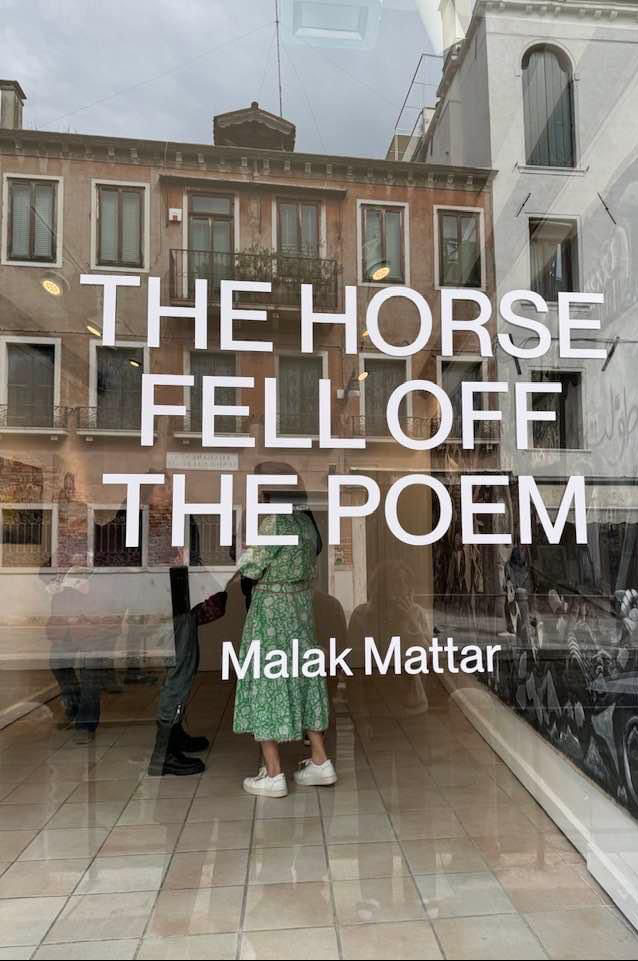

Her exhibition, though brief, was well attended. At the same time, a number of her preparatory sketches, under the ensemble title Cuts were displayed as part of London’s AWAN Festival from March 1-30, 2024. The impressive turnout to both of her exhibitions as well as the open studio events that she hosted during her residency is a testament to Mattar’s talent and popularity, particularly in a landscape where artists and cultural workers are being censored and intimidated against speaking out on Gaza. Mattar’s work is now on view in Venice in a solo exhibition titled The Horse Fell off the Poem after a poem by Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish. Curated by Dyala Nusseibeh, her exhibition takes place from April 16-June 14 at the Feruzzi Gallery in Dorsoduro, Venice. Its dates coincide with the 60th edition of the Venice Biennale, which has been shrouded in controversy since the announcement that Israel would not be excluded from participating in the Biennale as the thousands of signatories (including Mattar) of the Art Not Genocide Alliance campaign demanded, maintaining that there be “no business as usual during a genocide.” (Instead, Israel’s representative artist chose to lock the pavilion while keeping the art visible from a distance, in what many have deemed “an opportunistic gesture.”) While multiple artists taking part in the Biennial have chosen to feature Palestine in their works, Mattar’s solo exhibition, with its visceral paintings of the genocide displayed outside the scope of the Biennale’s “business as usual” resonates that much more powerfully.

That visceral quality of Mattar’s paintings is achieved through scaled-up emotive renderings of devastation, death, and destruction. It invokes hapticity, what Tina M. Campt, Black feminist theorist of visual culture and contemporary art, has described as the “labor of feeling beyond the security of one’s own situation,” and “the labor of love required to feel across difference, precarity, implication and suffering.” The frequencies of her resounding and resonant work evoke a multi-sensory experience, that, while devastating and heavy, demands to be felt.

Through his drawings on the Massacre of Tel Al-Zaatar, Dia Azzawi sought to “create a memory that persists (tatawasal) against oppression (dhid al-qhur). Not a memory of violence and oppression per se, but a memory capable of standing against oppression.” In that same vein, Mattar’s work, more than mere documentary, asserts a subjective memory, a memory of an entire people and their collective trauma, that persists against oppression.