Art and a history of violence collide in Rushdi Anwar’s exhibition Endless Tears in the Garden of Eden, on now at London’s Ab-Anbar Gallery, while historian James Barr, one of the artist’s sources, considers the effects of the Sykes-Pico Agreement on the Middle East today.

Malu Halasa

In the 19th century Biblical archeologists and missionaries scoured the Holy Land for evidence of the Bible’s historic authenticity. For many, the Garden of Eden was the river basin of the Tigris and Euphrates, in ancient Mesopotamia, now Iraq. For the Kurdish artist Rushdi Anwar, Eden is his much maligned, unrecognized country of Kurdistan. Like those Biblical archeologists, he too has searched the landscape and picked through the ruins. However, unlike them he has found actual proof of violence, historic neglect and obfuscation.

In the exhibition Endless Tears in the Garden of Eden, 2011–2023, at London’s Ab-Anbar Gallery until May 18, installation, sculpture, photography and sound art illuminate a history of violence and how a once secret deal between the colonial powers of Britain and France continues to divide people and land in what is considered “the Middle East.”

The installation “We Have Found in the Ashes What We Have Lost in the Fire,” 2011, opens the exhibition. It consists of mixed media embedded in twelve wooden boxes, each of which shows a different, charred and fragmented element from the life of Christ.

The artwork was inspired by Anwar’s visit to the town of Bashiqa, ten miles from Mosul, on the plains of Nineveh, in a disputed area between Kurdish and Iraqi forces. In 2014 ISIS attacked the town and murdered or sold its Yazidi, Assyrian and Shabak, Kurdish and Arab inhabitants into slavery.

The visit profoundly affected the artist. As Anwar writes in the Artwork Brochure that accompanies the exhibition, Bashiqa was “a ghost town in pieces filled with waste and destroyed weapons … I found civilian clothing for women and children belonging to those murdered by ISIS. It was an extremely heartbreaking moment for me — a Kurdish refugee whose people have endured ethnic violence and religious persecution for years.”

In the wreckage of one of Bashiqa’s Orthodox churches he came across the remnants of lightboxes from the church’s original interior, filled with key moments in Christ’s story. Anwar had wanted to take them, he admitted during his artist’s talk in the gallery, but the Peshmerga authorities guarding the town prevented him. They said everything had to stay as it was, although whether as a memorial or evidence of a war crime is unclear. In the end Anwar made his own.

The Islamic geometry featured on the boxes’ glass lids were taken from the period of Al-Andalus (711 to 1492 AD), often depicted as Islam’s golden age of peace and cultural prosperity in Spain. However, the orange color of the patterns gives the artwork a jarring, contemporary twist. The color comes from the jumpsuits prisoners wore in Abu Ghraib prison and Guantanamo Bay.

On first reading, an artwork mosaic of two of the three monotheistic religions, Islam and Christianity, have been tainted by violence — both Western and homegrown — and live side-by-side in the same place or object. Although a closer inspection of the exhibition reveals more nuanced complexity.

A similar overlay of history, violence and religion appears in another of the exhibition’s installations, the digital print photography on paper of “When the World Pushes You to Your Knees, You’re in the Perfect Position to Pray.,” 2023. (Anwar’s titles for his work are circuitous and witty in a backhanded, slap in the face kind of way.)

The Bashiqa church appears yet again, only this time in three colored photographs documenting the church’s burnt-out interior. One is of a lightbox, with Christ nearly crushed by the weight of the cross. These images have been seemingly hung on a black and white photograph of Mosul’s 900-year-old Al-Nouri Mosque. It was here in 2014 that Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi (1971–2019) announced to the world that ISIS was to be known as “the Islamic State,” and he was its caliph. The mosque had been a local landmark for its unusual overhanging minaret (called “the hunchback”), which ISIS then blew up in 2017.

Even the frames around the pictures from the church are not without significance. They are described by the artist as: “colonial black frames,” which “allude to the romanization of faith in the Western historical imagination.” By the time the British and American religious scholars set their sights on the Mashriq Middle East, including Mesopotamia, the damage was already done, and Christianity had been given a particular look, with little traces of its origins. Christ is always depicted as white, never brown; not only in the Iraqi church’s lightboxes, but in Western churches and cathedrals, and classical European paintings for more than a thousand years. Even in the Middle East, the birthplace of Christianity, church imagery mimics established Western norms.

Islam, too, underwent its own permutations and transformations. The early Muslim conquests of the seventh century took the religion to regions far from the Arabian Peninsula, and immersion in other cultures changed its aesthetics. In more recent times, the radicalization that had taken place in Abu Ghraib and the prisons of Chechnya fuelled a virulent militancy among the Daesh homegrown and foreign fighters who subsequently laid waste to towns like Bashiqa.

Violence in the region meets foreign collusion in Anwar’s sound art installation “Listen Again to the Drum Sound Rising in the Air; The Truth is Treason in the Empire of Lies.,” 2023, made from brass, walnut and teak woods, and a Bluetooth sound system and sound, in the shape of a 19th century gramaphone. Here, centuries come together in a cascade of sound: radio broadcasts of historic news events from the first World War, the martial Iraqi national anthem, televized news conferences all the way through to George Bush, Donald Trump and the social media of today. It’s a post-modern soundtrack to empire, where ISIS calls to prayer vie with bombing from American B52 bombs.

Sykes-Picot

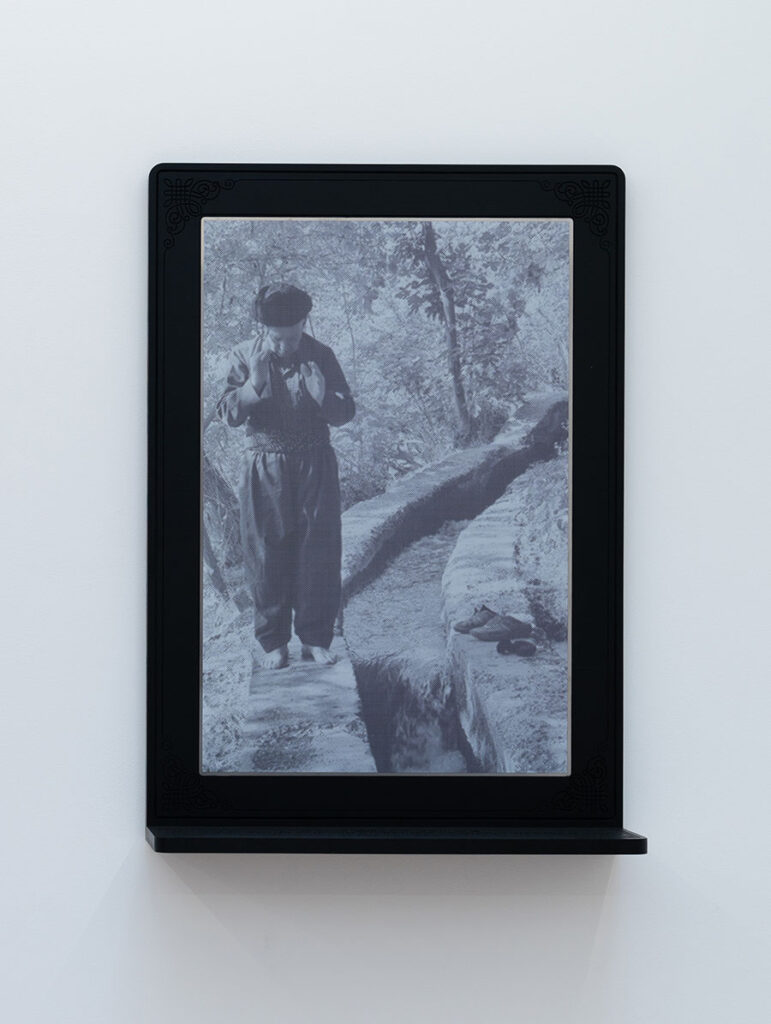

Colonization in the Middle East has taken place on myriad levels and not just in religious faith or iconography. Perhaps its greatest impact has been on the borders of the Middle East. In Anwar’s enigmatic black and white photograph, a man in traditional Kurdish clothing stands beside a narrow channel of water. The explanation lies in the artwork’s title: “The Invisible Line — He Prays in Iraq, His Shoes in Iran, Both Are in Kurdistan.,” 2023.

The exhibition’s set piece is an ongoing series from 2023, A Hope and Peace to End All Hope and Peace, about the Sykes-Picot Agreement, a secret pact between France and Great Britain that sought to divvy up the region over a hundred years ago, with the assent of Imperial Russia. For the installation, “When You Pray for Black Gold, You Must Deal with the Burning Smoke Too.,” 2023, two color-coded walls and portraits of the agreement’s architects — blue for the British diplomat Mark Sykes (1879–1919) and red for the French civil servant François Georges–Picot (1870–1951) — stare out over a traditional, hand-woven Kurdish prayer mat facing east towards Mecca.

In 1916, Sykes and Georges–Picot drew a diagonal line from Acre on the Mediterranean Sea across nearly 8,000 miles to Kirkuk, near the Iranian frontier. It was to partition the vast territory that still belonged to the Ottoman Empire; France and Britain wished to punish the Turks, since they had sided with Germany in World War I (then two years old), oust them from the region, and share the spoils. The areas north of the line (Turkey, Kurdistan, Syria and Lebanon) were to go to France, while the lands to the south (comprising most of what is now Israel, Palestine, Jordan and southern Iraq, with some access to the Mediterranean) were allotted to Great Britain. The secret agreement was leaked to the public after the Bolsheviks overthrew Tsarist Russia. Subsequent treaties enforced variations of the Sykes-Picot line.

For Rushdi Anwar, the agreement has had dire consequences. Not only did it ignore Kurdish sovereignty and divide a people and their lands between Turkey, Syria, Iran and Iraq. Sykes-Picot also contributed to disenfranchisement of Palestine and the violent tensions that continue to wrack the region today, most recently the war on Gaza. The artist emphasizes this point by showing a map printed over the portraits of Sykes and Georges–Picot, and embroidered on the prayer mat. The British Foreign Service map, published in 1964, the year the PLO was formed, shows the ethnic groups that have been affected by the Sykes-Picot and the treatises that followed.

Interestingly, the exhibition’s “archive” table includes among its research resources, the foremost history of the agreement, A Line in the Sand: Britain, France and the Struggle That Shaped the Middle East by James Barr. After the October 7th attacks in Israel, the BBC called him in to present each night for a week “A Complicated History” about Israel and Palestine. I contacted the author and historian to gain a deeper understanding of the background context to Anwar’s exhibition.

Today in Britain and in France, only a few people remember Sykes-Picot, what the agreement did and its ramifications today. Barr begins our Zoom conversation by discussing a 2013 survey, which was taken on behalf of the British Council. The survey had shown: “Forty-one percent of Turkish respondents and 59 percent of Egyptian respondents had heard of the Sykes–Picot Agreement, compared to only nine percent of respondents in the UK and eight percent in France — the two countries which made the agreement.”

Barr adds, “Daesh raised the issue in 2014, when they talked about ‘erasing the line.’”

The physical frontiers of the Middle East are the result of the agreement. “Look at that diagonal line,” he says, “It is not necessarily absolutely where the modern border between Syria and Iraq and Jordan is. But you can see that it comes from that map; it doesn’t come from anything else. Sykes-Picot set the stage for that post [World War I], the last gasp of colonialism. It was a deal to carve up the Middle East, between Britain and France. And that’s exactly what it did then, even though the details of it were not as per the map because of Turkish nationalism and other issues. But that was the intention and that is what happened. That is why the modern states [in the Middle East] look the way they do.”

Is the current violence in the region the fault of the Sykes-Picot agreement?

As a historian, Barr understandably takes the long view. “You can’t blame it all on this agreement. It is a symptom of one of the Middle East’s problems, which is that it gets fought over by great powers going right back to Cyrus’ time in 500 BC. [Going back further] the Egyptian pharaohs were always trying to extend their territory into what we think of as Lebanon and Syria now.”

His next comments about security resonate today, particularly with the war on Gaza.

“Geographically [the Middle East] is relatively open territory,” he explains, “there’s no natural frontier. Both people coming from east and west think that the further they push the frontier, away from their heartland, the more security they will have.”

He was intrigued to hear of the discussions The Markaz Review’s managing editor Rana Asfour has been privy to in the literary salons in the region where people have been wondering why they should consider themselves a particular Arab identity. What if Sharif Hussein ibn Ali (1854–1931) and his dream of a greater Arab nation-state-territory had come into existence? In light of people questioning their identities in relationship to a colonial demarcation of the region — is this also a holdover from Sykes-Picot?

Barr agrees, “In the sense an Iraqi identity didn’t exist before the creation of the State of Iraq in the 1920s and a sort of independence in the 1930s, with the British still, sort of heavily behind the scenes. So those things are a modern addition. They do come out of the post-war settlement that Sykes-Picot was the blueprint for. But I don’t think that means that the identities are not genuine.”

For him, identity and affiliations are nearly always mutable, contingent — especially in the Middle East. “The danger always is, you think, ‘Okay, it’s all a construct,’ but then when you start looking at identity that’s not to say it’s not a genuine identity. Lots of things, whether it’s football teams or history … have had an effect.”

Cultural identity in different countries is also connected to political and social histories, particularly when one considers, for example, the Kurds and the Palestinians. The violence against them and the lack of recognition of their rights to individual statehood, by Turkey and Israel respectively, have also become part of their national narratives and identities too.

Anwar’s hometown is Halabja, where Saddam Hussein’s chemical attack took place in 1988, near the end of the Iran–Iraq war. At the artist’s talk, the co-founder of Ab-Anbar Gallery Salman Matinfar shows me another book from the archive table. Matinfar leafs through a compendium of war photographs by Iranian photojournalists to one of the images. The house that belonged to the artist’s family in Halabja appears in a photograph taken after the chemical attack.

For the photographic installation, “A Few Lines of History,” 2023, Anwar took photographs in the aftermath of the chemical attack, then re-photographed the images and darkened them with soot. They were displayed like double- or triple-page spreads of a book across seven shelves. But the story of murky photographs is unclear as though to emulate the confused reality they both describe and critique. It is as though time and memory coupled with the indifference on the part of the international community have obscured real meaning. Perhaps Anwar is also suggesting that the Western powers soon moved on to the next Middle East war, and after Halabja, there was no justice for the Kurdish people.

At this time, the parallels between the Iran-Iraq war and the current war on Gaza couldn’t be clearer. Both wars were fought with American weaponry the U.S. government gave to its allies – back in 1980–1988 to Saddam Hussein, and now in 2024 to Binyamin Netanyahu.

In Endless Tears in the Garden of Eden time stands still, lessons remain unlearned.