Tracing the historical journey of the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) from ancient times to its contemporary political significance, the subsequent exploration dives into its evolving identity, adapting to shifting socio-cultural norms. Furthermore, it examines its relevance in the context of cultural appropriation and gender identity while also addressing the contemporary challenges it encounters.

Rajrupa Das

After much contemplation and hesitation, I have decided to delve into the topic of the “Palestinian Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة)”. Initially, I felt uneasy about writing on a subject I, like many non-Arabs, had limited exposure to. My understanding of the deep emotions attached to it was minimal. While I wholeheartedly support the Palestinian cause and recognise their enduring struggle, adversity, and dehumanising conditions, it is not a cause that directly impacts me. Consequently, it felt challenging and somewhat inappropriate for me to write about an article of clothing that has become symbolic of their suffering, resilience, hopes, dreams, and faith in a brighter future.

Nevertheless, reflecting on my country’s own history, marked by two centuries of colonialism, akin to apartheid treatment, and ruthless subjugation, I have come to recognize that I may possess some understanding through my collective experiences—shaped by education, culture, and environment. This realization has given me the courage to proceed and pen down this article.

The term Palestinian “Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة)” may evoke images of a black and white striped kerchief styled around people’s heads and necks. However, until the recent conflict, it remained relatively insignificant to non-Arab laymen. Amidst the current turmoil, the world has renewed its acquaintance with this black and white woven fabric, emerging as a symbol of the Palestinian cause and one of the region’s most recognizable political symbols. Over the past 75 years, this fabric has witnessed pivotal moments, stirred controversies, and encapsulated a spectrum of emotions. In this article, we will provide a brief history and explore its cultural and symbolic significance while also introducing new arguments and raising pertinent questions.

Etymology and Ancient Origins

The story of the “Palestinian Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة)” is not a recent one, and neither is its association with Palestinian liberation. The Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) has deep roots that stretch back centuries in the Levant Arab landscape. Etymologically, the word “Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة)” is a derivative of the name of the city of Kufa in Iraq, meaning “from the city of Kufa.”

As such, its roots could be traced back to ancient Mesopotamia (c. 3100 BCE), when people living within the Tigris and Euphrates River system used to cover their heads to protect themselves from the elements. Its usefulness in the desert climate later percolated into every society across the diverse communities of the region.

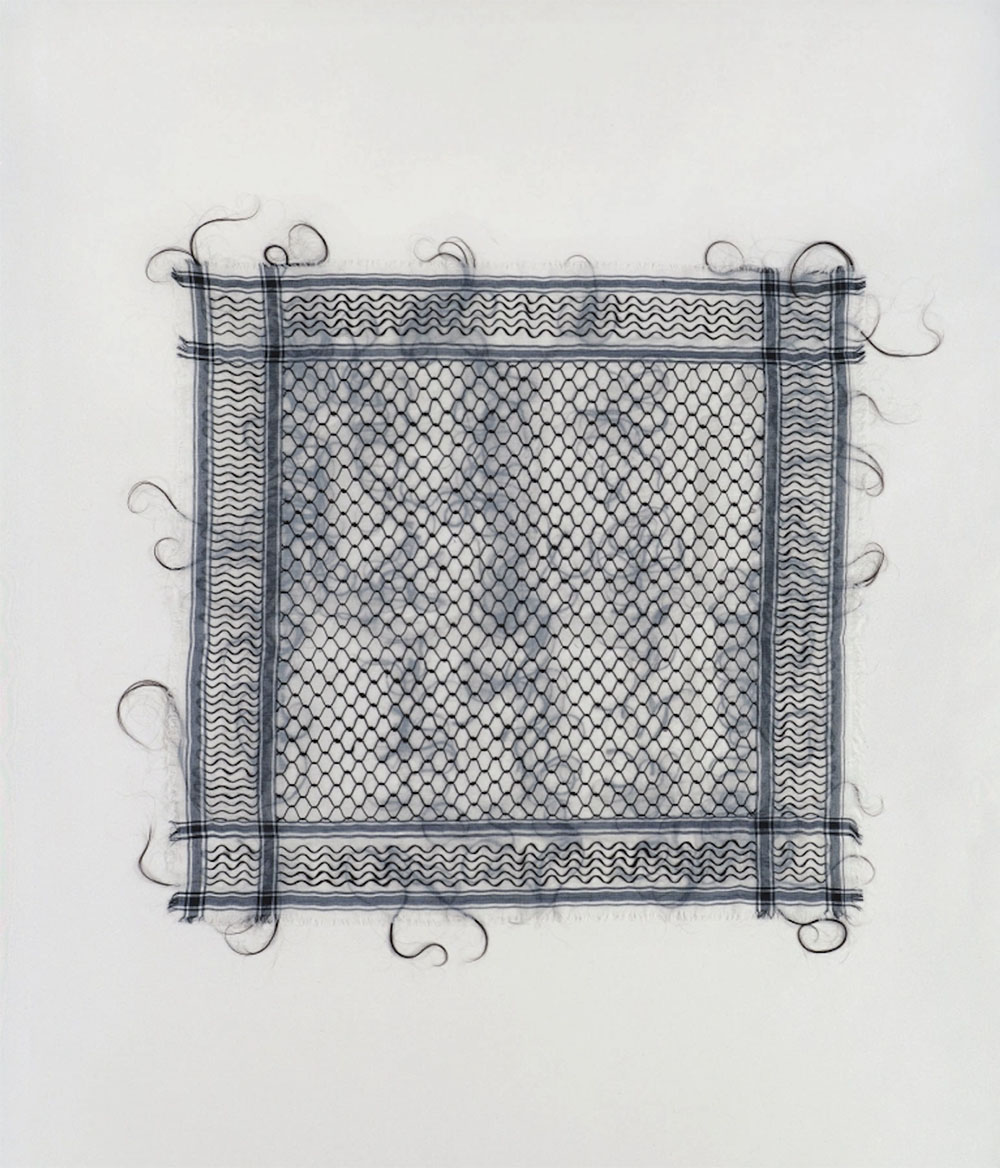

With its roots traced back to Mesopotamia, the head covering in Iraqi culture, particularly the shemagh (شُمَاغ šumāġ), carries various nuances, ultimately signifying prestige and status. Legend has it that the Sumerian fishermen, seeking protection from the scorching summer sun, ingeniously placed a fishing net on their heads, evolving over time into a distinctive headgear with its own unique name.

The shemagh (شُمَاغ šumāġ), with its fisherman’s net design, water lines, and fish shells, is considered a talisman, believed to ward off evil even today, maintaining a connection to its Sumerian origins. Later worn by priests and kings who adorned white clothes and a black net made of sheep’s wool symbolizing a fishing net, this headdress gradually merged with the shemagh (شُمَاغ šumāġ), known in the Iraqi dialect as the “Yashmagh.”

Over time, the Yashmagh transitioned from being an accessory of the ruling and sacred elite to becoming the most popular headdress in Mesopotamia and its neighbouring regions. It became an integral part of the cultural identity, symbolizing prestige and status for individuals across various Arab communities. Each community adopted the wearing of the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) with their own interpretation and twist to it. In fact, until the turn of the 20th century, communities of all faiths and tongues from the region sported the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة).

Thus, the iconic black and white Iraqi shemagh (شُمَاغ šumāġ), also known as Yashmagh, Ghutrah (غُترَة), Cheffiyeh (چِفّية), and Jamadani / Jimidani, serves as a living testament to this rich heritage, transcending geographical boundaries and becoming a symbol of cultural identity for the Palestinian people in their struggle against British occupation since the 1930s.

A century-old tradition

Traditionally crafted from cotton and wool and worn by Bedouins and villagers in the Ottoman-controlled Levant Arab region, the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) evolved into a symbol of class struggle embedded in the psyche of the local people much before the Arab-Israeli conflict. While the affluent upper and middle-class Arabs embraced symbols of Ottoman style like the “Tarbush” or “Fez,” individuals from modest backgrounds favoured the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة). Many Jews, Christians, and Muslims in the Levant, such as in Palestine and Iraq, chose the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) to mark their authentic local connection, setting themselves apart as “sons of the soil” within the Ottoman and later British-controlled Palestine.

In the initial decades of the 20th century, Palestine underwent significant transformations that laid the foundation for the contemporary identity of the black-and-white fabric. In the 1930s, during the British mandate, the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) emerged as a unifying national symbol, supplanting the Ottoman’ Fez’ with widespread support. Concurrently, it became a potent emblem of resistance against British rule. As Palestinian freedom fighters, known as “fidā’īn,” predominantly from the rural areas, prominently wore the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) during their anti-British activities, a pervasive desire for a liberated Palestine spread across the entire population, regardless of class or economic status. This collective sentiment led to the widespread adoption of the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) by the general populace, serving to conceal the identity of the freedom fighters and facilitating their seamless integration with the rest of society.

20th Century Political Symbolism

Following the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 and the subsequent displacement of thousands of Palestinians, the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) began its evolution as a symbol of resilience against occupation and the escalating mistreatment of the local population. Worn by both those who were displaced and those who remained, the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) swiftly became emblematic of the Palestinian cause. In the 1950s, a seemingly arbitrary decision by British officer General John Glubb to designate the black and white fabric for Palestinian soldiers, distinguishing them from their Trans Jordanian counterparts wearing the red and white shemagh (شُمَاغ šumāġ) in the Arab Legion, ultimately solidified and popularized one of the most visually distinctive political symbols of the 20th century.

It is intriguing to observe that during the British mandate period, the red and white Trans Jordanian kerchiefs, commonly called shemagh (شُمَاغ šumāġ), were produced in British cotton mills and served as the standard headwear for the British colonial police force in Palestine. Over time, these head coverings found adoption within the Sudan Defence Force and the Libyan Arab Forces, too.

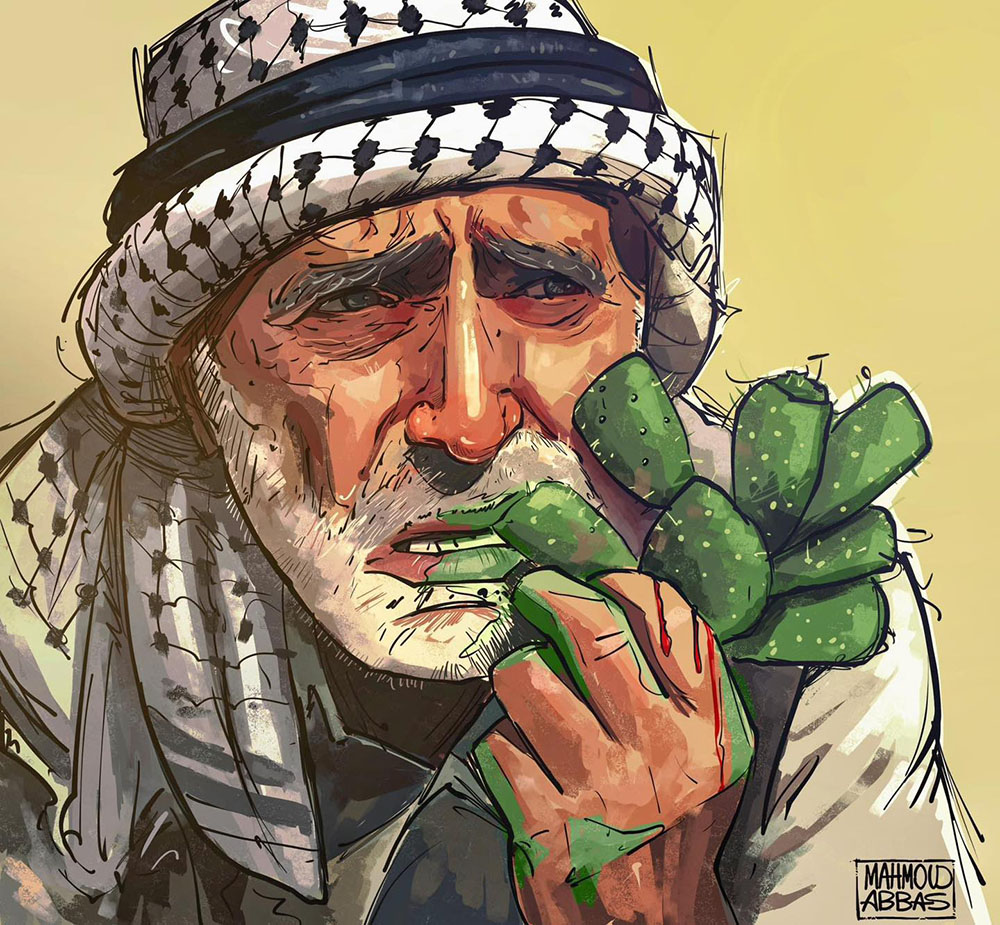

In the subsequent years, as the occupying government prohibited the display of the Palestinian flag (1967-1993), the black and white Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) underwent a transformation, becoming the unofficial flag of Palestine. This shift in symbolism gained prominence through the actions of the Palestinian resistance and prominent political figures, notably the late Yasser Arafat, former chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization and President of the Palestinian National Authority. Internationally, other political figures, such as former South African president Nelson Mandela and the late Cuban revolutionary and president Fidel Castro, were known to don the black and white Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) as a demonstration of solidarity and support for the Palestinian cause.

The Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة): Gender Issues and Pop Culture

The Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) evolved into a symbol embraced by Westerners as an emblem of solidarity with the resistance movement. It swiftly became an iconic representation of anti-war activism during the peak of the Cold War throughout the 1960s and 70s. However, the hijacking of a TWA flight in 1969 by the first woman hijacker, Leila Khaled, cast a shadow over the Kūfīyah’s (كُوفِيَّة) image in the Western consciousness. Ironically, as media outlets circulated images of Khaled, a Palestinian refugee and former militant, brandishing an AK-47 and sporting a Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة), the gendered perception of the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) was challenged. No longer confined to being worn solely by men for a cause, it emerged as an accessory suitable for both men and women.

Fascinatingly, the kerchief, a headgear in the Arab world, has consistently been a gender-neutral accessory, embraced by both men and women across centuries. Referred to as ‘hatta (حَطَّة),’ ‘Futah,’ and other regional names, its styles and materials vary for women, showcasing regional and communal distinctions.

Cultural Appropriation or A New Identity: A Debate

In the 1980s, the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) underwent a paradigm shift in the West. Transitioning from its origins as a symbol of the Palestinian cause and anti-war sentiments, it transformed into a broader emblem of liberalism and anti-authority. Embraced by pop culture icons, the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) became a distinctive accessory within the ‘hipster’ subculture by the early 2000s, frequently spotted in crowds at music concerts alongside Che (Guevara) T-shirts.

While the fashion industry globally witnessed the widespread and unapologetic appropriation of the distinctive black and white patterned fabric throughout the 2000s, the Kūfīyah’s (كُوفِيَّة) transformation into a popular fashion accessory by various brands ignited intense debates too.

It is intriguing to observe the incorporation of symbolism from ancient Mesopotamian fishermen of the Tigris-Euphrates Valley into a Mediterranean context. While the fishnet pattern retains its resonance with the coastal roots of Palestine, the substitution of fish scales with rows of olive leaves holds significant meaning. These leaves symbolize perseverance and endurance, establishing a profound connection to the Palestinian soil and vegetation—an emblematic representation of the region. Additionally, the bold lines, once representative of rivers in the Iraqi context, now take on a new meaning as symbols of robust trade routes in Palestine. Positioned at the crossroads of Europe and Asia since ancient times, these lines encapsulate the historical significance of trade integral to the region.

These observations extended beyond concerns of mere appropriation, delving into complex questions about whether such usage inherently disrespects the political and historical context associated with the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة).

This prompts the inquiry of whether the donning of the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) for a cause by non-Arabs today constitutes cultural appropriation or transforms the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) into a broader global symbol of freedom and liberation. An analogy for this debate can be drawn from UNESCO’s declaration of February 21st as International Mother Language Day, which commemorates the 1952 massacre of students in Dhaka, Bangladesh (then East Pakistan), during a rally advocating equal rights for Bengali alongside Urdu in the Pakistani Parliament.

Against the backdrop of a declining Palestinian industry, the Hebrawi Textile factory in Al Khalil/Hebron stands as the solitary producer of authentic Palestinian Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) today, operational since its establishment in the 1960s. As local industries face challenges, the global demand for Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) is predominantly met through the power looms of China. Should this reduce the importance of the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) as the symbol for the Palestinian cause?

In the wake of escalating global Islamophobia post-9/11, the West has unabashedly associated the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) with symbols of terrorism and animosity. Amidst ongoing protests and demands on both sides, since the recent clashes starting October 7th, 2023, there has been a growing trend of anti-Islamic sentiments directed at individuals wearing the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة), contrasting with the comparatively unscathed acceptance of the blue and white flag. This situation prompts a crucial question, perhaps the most critical question of all: Does the black and white kerchief exclusively symbolize the cause (liberation from suffering and struggle) of a specific faith community in Palestine?

In conclusion, the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) continues to transform beyond geographical and material constraints, prompting questions about its meaning and global significance. Much like the watermelon, a symbol echoing the Palestinian flag, the Kūfīyah (كُوفِيَّة) has ventured into new realms of expression. Despite restrictions on its use in political rallies in the West due to perceived ‘provocative imagery,’ it persists in evolving, finding alternative channels like tattoos and henna for its continued expression.

This article was first published in the the Zay blog as “The Story of Keffiyeh,” Part 1 & 2.

Where are Palestinian keffiyehs made? article here:

https://www.charles-arthur.com/ever-wondered-where-keffiyehs-are-made

History must be redeemed for it to be true, and curiously, it begins with etymology, defined as a branch of linguistics, investigating name/word histories. I am perplexed. Someone, please elaborate on how 🤔 a Middle Eastern land is referred to as “Palestine,” originally in the Egyptian hieroglyphics as pwrꜣsꜣtj Peleset, transliterated into ancient Hebrew, P’léshet פְּלָשֶׁת precise ancient Hebraic definition of this adjective from the primitive root verb is “pelesh, dividers, penetrators” or “invaders.” ??? Then P’léshet entered into Koine Greek as Παλαιστίνη (Palaistínē, “Philistia and the surrounding region”),to the Latin Palaestinae (Philistia), and finally the Anglicized Latinized modernized “Palestine.”

Quelqu’un peut-il nous dire quel nom les habitants d’un pays du Moyen-Orient ont donné à leur propre territoire, sans passer par des noms donnés par d’autres, pwrꜣsꜣtj Peleset, P’léshet, Palaistínē, etc.

Well, blue and white is associated with democracy. The other side… lol. Nice spin though. January 20th cannot come soon enough.

The flag that you call the Palestinian flag was created by an Egyptian Islamist in 1964 and represents the extermination of all non-muslims, four to five tyrannical Islamic caliphates, each color representing one of those caliphates. It has no relationship with Gaza, Judea, Samaria(West Bank), or the Levant as a whole. It is a flag of Islamic terrorism and colonization of the Levant commanded by Egyptian Islamists. The origin of Keffiyeh is thus non-Islamic, non-Arabic, the cultures of Mesopotamia, Persia, Babylonia, Assyria, Arakadians, later Beduins who were subject to destruction and ethnic cleansing by invading Arab/Muslims with start from Rashidun. a more appropriate representation should should be the resistance against Islamic terror destruction of cultures, wars, genocides, invasion, and colonization.