* The geographical term Middle East is not neutral, but Eurocentric and has its origin in colonialism.

Trembling Landscapes is on view through 3 January, 2021. The exhibition title is borrowed from Lebanese artist Ali Cherri’s series of lithographic prints Trembling Landscapes (2014-2016).

Nat Muller

Landscape is a charged notion in the Middle East. On the one hand, representations of landscape engage with a heady mix of national and natural borders, tussles over resources and territory, and (colonial) history. On the other hand, it is a rich source of identity, tradition and imagination.

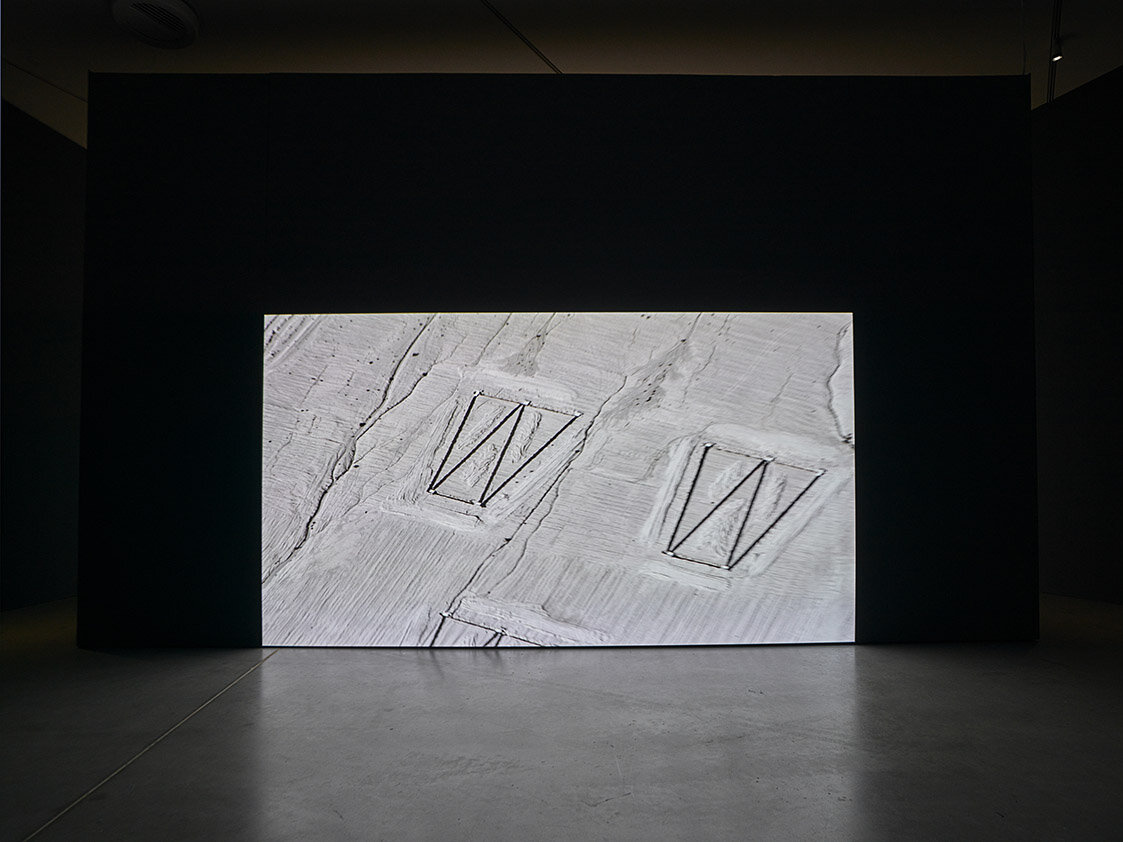

In Ali Cherri’s series of lithographic prints, Trembling Landscapes (2014-2016), aerial maps of Algiers, Beirut, Damascus, Erbil, Mecca and Tehran reveal political and geological fault lines. An apt metaphor for an exhibition that draws in equal measure on geopolitics and poetics, including some of the Arab world’s most prominent artists working with video and film.

The artists relate to landscape in various ways. They do not shy away from interrogating how beauty, folklore, ideology, colonialism and violence are ingrained in how landscape is understood, conceptualised, visualised and imagined.

In this exhibition, the participating artists challenge and reshape views of the region by drawing on a host of complex and entangled issues, ranging from geography and conflict to belonging. Trembling Landscapes: Between Reality and Fiction includes works by Basel Abbas & Ruanne Abou Rahme, Heba Y. Amin, Jananne Al-Ani, Ali Cherri, Joana Hadjithomas & Khalil Joreige, Mohamad Hafeda, Larissa Sansour, Hrair Sarkissian, and Wael Shawky.

What binds these artworks together is that they explore landscape as a versatile trope for telling stories about the past, present and future, whether rooted in reality or fiction.

In his video The Disquiet (2013), Cherri follows a similar logic by tracing the history of earthquakes in Lebanon, seamlessly combining seismic and political catastrophe by inviting the viewer to consider longer timescales than those of recent political events. It is illustrative of an exhibition that challenges and reshapes views of the region by drawing on a host of complex and entangled issues, ranging from geography and conflict to identity and the imaginary.

Imaging and mapping technologies help shape the way we look at landscape. Egyptian artist Heba Y. Amin looks at technologies used by colonial powers to survey the landscape, as well Filmscapes of the ‘Orient’ in historical travel accounts. In The Earth is an Imperfect Ellipsoid (2016), she reframes geographies and inverts this colonial and male gaze. Irish-Iraqi artist Jananne Al-Ani interrogates the military notion of ‘mastery from above’ in Shadow Sites I (2010) and II (2011). Her dreamy aerial vistas of Jordan point to how developments in technologies of photography and film are intertwined with technologies of aviation. Here aerial surveillance maps the plundering of the earth’s resources (fossil fuels and ores) and suggests the weaponized view of a military drone.

Lebanese artist Mohamad Hafeda shows how the historical carving up of the Middle East in 1916 by the Sykes-Picot Agreement into English and French spheres of control and influence, and the 1917 Balfour Declaration in which the British government laid the groundwork for the foundation of the State of Israel, have created artificial borders that continue to resonate and destabilize the region to this day. In Sewing Borders (2017) he works with disenfranchized residents of Beirut, including Iraqi-Kurdish, Palestinian, Syrian and Armenian refugees who negotiate urban space in a city where they are marginalized.

For Palestinians suffering the consequences of Israeli occupation and landgrabs, landscape has for many decades been an important artistic trope to demonstrate a connection to the land and reclaim Palestinian historical presence. In the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, territory is the currency. Palestinian artist Larissa Sansour and artist-duo Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme draw on the fragmented and disappearing topography of Palestine in highly original ways to drive this point home. In the dystopian, yet humorous, science-fiction short Nation Estate (2012), Sansour circumvents Palestine’s issue with land contiguity, hampered mobility, checkpoints and closures by locating the entire Palestinian population in a luxury high-rise on the outskirts of Jerusalem. Abbas and Abou-Rahme take the viewer on a riveting and fast-paced audio-visual journey through the West Bank in which the character of the ‘incidental insurgent’ offers a speculative potential for change.

Although the exhibition is firmly rooted in the turbulent history and geopolitics of the region, other narratives unfold. For example, Egyptian artist Wael Shawky’s mesmerizing landscapes of Upper Egypt become a site of folklore, magic, ghosts and whimsy, rooted in Egypt’s rich literary tradition. The distinctive rural landscapes around the Nile’s riverbanks become an uncanny foil for the short stories of Egyptian writer Mohamed Mustagab, on which Shawky has based his scripts.

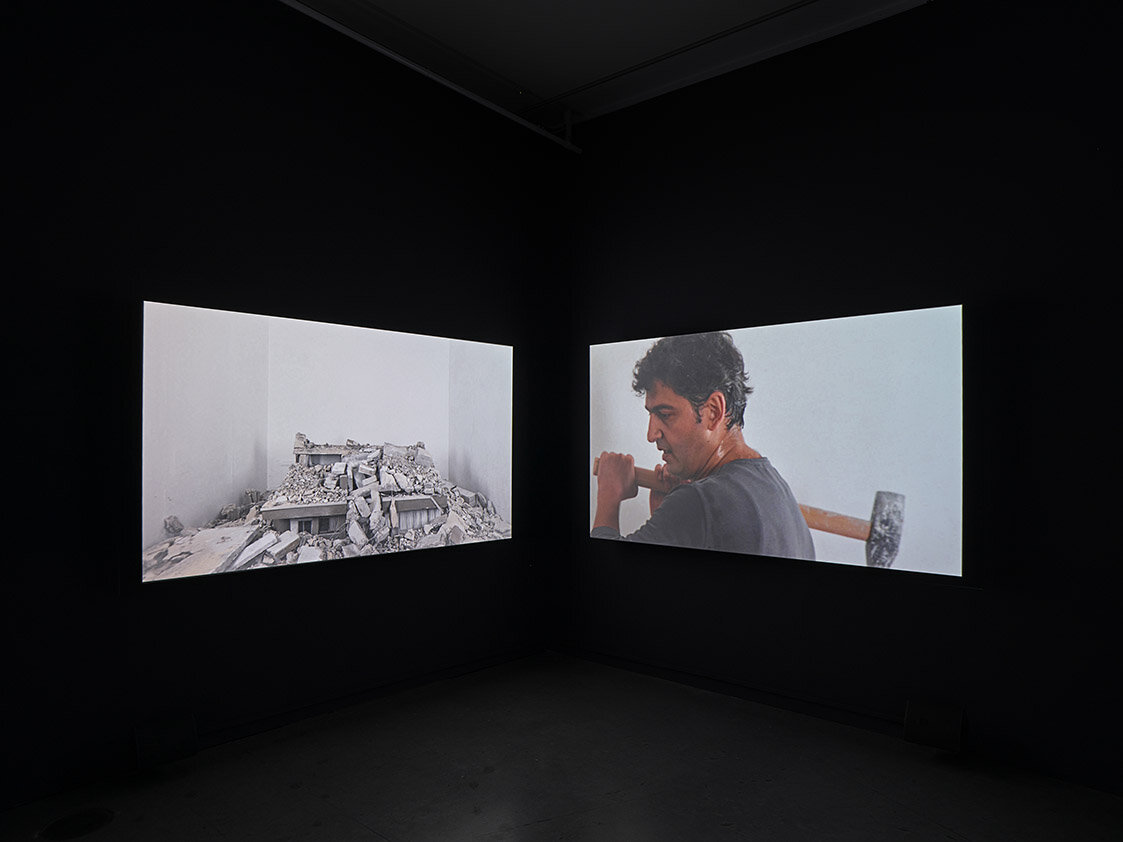

In the exhibition, landscape encompasses nature as it does cityscapes and the built environment, as well as emotional landscape. Syrian artist Hrair Sarkissian takes a deeply personal and autobiographical approach in his installation Homesick (2014). One screen shows a scale model of the artist’s parental home in Damascus gradually reduced to rubble, while the other shows Sarkissian swinging a sledgehammer. The work addresses conceptions of home and collective.

A similar sentiment is echoed in Waiting for the Barbarians (2013) by Lebanese artists and filmmakers Joana Hadjithomas and Khalil Joreige. Taking its cue from Alexandria-based Greek poet Constantine Cavafy’s 1898 eponymous poem on political inertia, the work shows a cityscape of Beirut composed from photographs and moving images. It presents the viewer with a mesmerizing yet ominous landscape of a city that has suffered incessantly at the hands of its corrupt rulers during the Lebanese Civil War (1975-90) and its aftermath. Seen in the light of the tragic port explosion that flattened a large part of the city on 4 August, this work becomes all the more poignant.

The exhibition was curated by Nat Muller, in collaboration with Jaap Guldemond and Marente Bloemheuvel for Eye, the Netherland’s film museum. This text was originally written for the exhibition brochure.