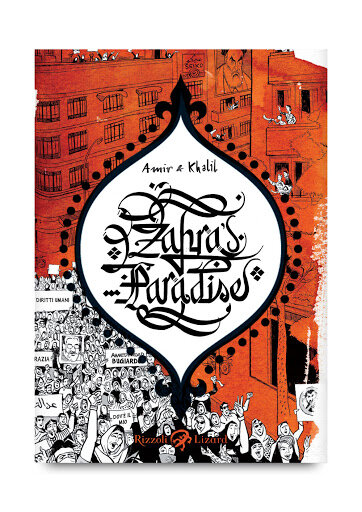

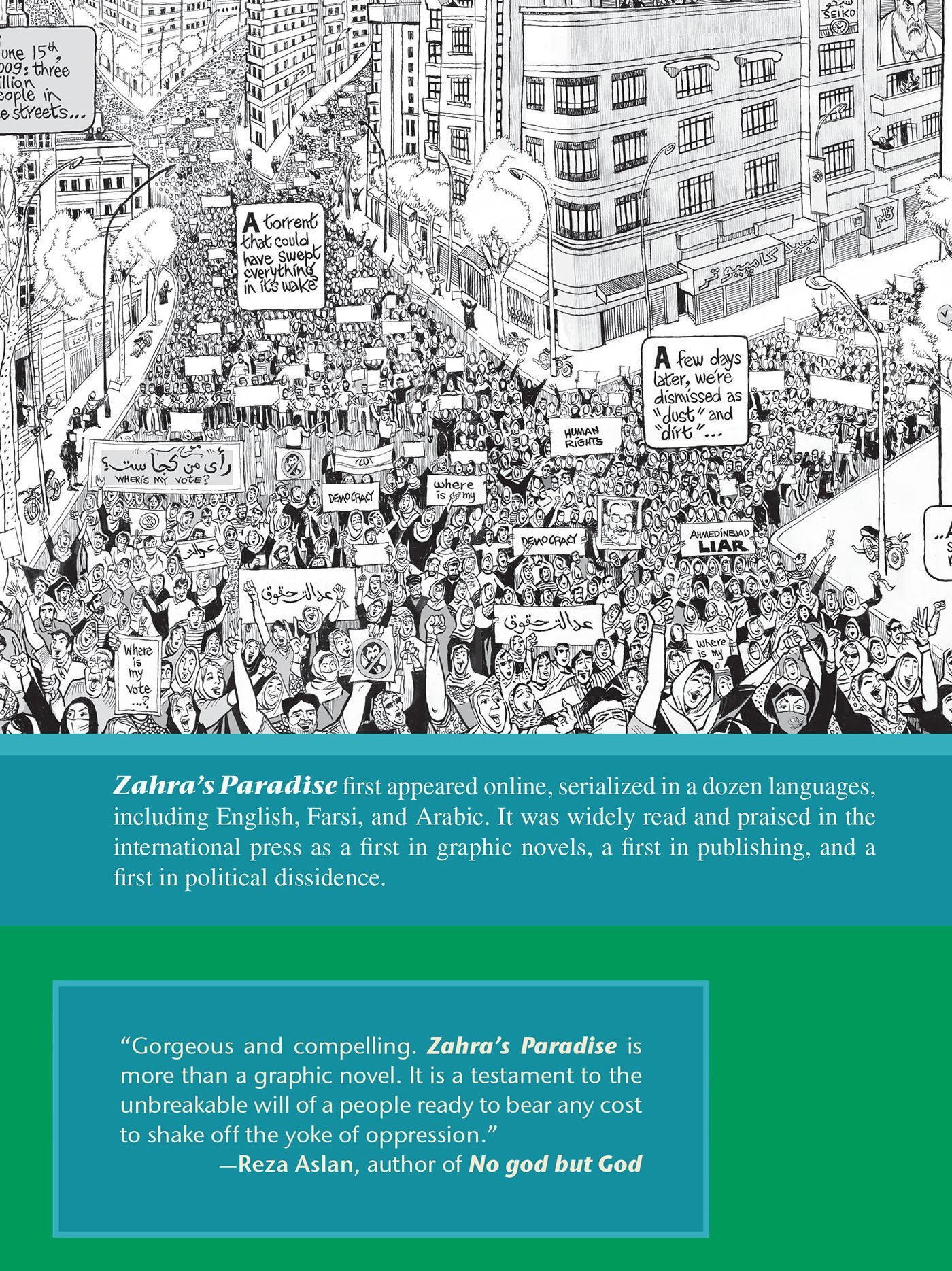

Zahra’s Paradise by Amir Soltani and Khalil was a first on the internet, a first for graphic novels, and a first in the history of political dissidence. <

<

From Zahra to Yasmin, from the Islamic Revolution to the Green Movement and the Arab awakenings, Spring is inextinguishable

Mischa Geracoulis

Just as Punxsutawney Phil saw his shadow on Groundhog Day 2021, and predicted another six weeks of winter, so too for the “Spring” uprisings. No longer simply symbolic of the prediction of prolonged winter, “Groundhog Day” provides a go-to trope with multiple applications. Synonymous with another day in the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic lockdown, it also illustrates hibernation—albeit forced—of the uprisings that began ten springs ago. Reflecting back on Amir & Khalil’s 2011 graphic novel, Zahra’s Paradise, the long shadow looms.

A current reading of this historical fiction revisits a gut-wrenching elegy for Iranians beaten down, locked up, or disappeared, whose crime was to dare to stand up for civil rights. Replete with a chilling list of 16,901 names compiled by the Omid Memorial project, the book, among other things, attempts to memorialize the lives lost to the repressive Islamic Republic. The story’s graphic form makes it accessible to wide audiences, but by no means is it entertainment. While Zahra’s Paradise details the brutalities of a place-specific dictatorship, it’s not hard to extend the shadow across borders.

In the February 2021 issue of Responsible Statecraft, human rights leader Sarah Leah Whitson writes that though each was unique, the spring uprisings in Egypt, Tunisia, Syria, Yemen, Bahrain [and the Iranian Green Movement] inspired one another. Amir & Khalil, in their book’s “Afterwords,” explain the connection as a torch relayed from “Zahra to Yasmin.” Zahra represents Iran’s uprising, and Yasmin is for Tunisia’s. These protests, Whitson clarifies, were not against imperialism or foreign occupation, but about citizens of individual nations rising up against native-born tyrannical regimes to claim their rights and freedoms. Without meaningful transnational support for their democratic aspirations, however, the region’s powers have done their best to extinguish the spirit of civil society, suppressing chances for fresh popular movements to spring up.

Dedicated to the suppressed, the absent, and the fallen, Zahra’s Paradise tells the story of governmental crackdown and spring forestalled. Hope for freedom, it would seem, is beaten back and buried, if the repressors have their way. Ten years later, Whitson’s description of “Springs that end in cruel winter” is on par with the groundhog’s foreshadowing in 2021.

As for the novel, it’s a mother’s anguished search for her teenage son who doesn’t come home from a march in Freedom Square. Aptly named Zahra, she eventually confronts the awful truth of her son’s disappearance. Despairing, Zahra begs for her son to breathe. Reeling forward to a different time and place, this could be George Floyd’s mother. “I can’t breathe” could be the rallying cry spilt over from Green to Black, from Neda (Agha-Soltan) to George.

Zahra’s Paradise—both the story and the eponymous giant cemetery outside of Tehran—might lend itself as synonymous for refugees subsumed by the Mediterranean Sea, migrants given over to the ravages of the Sonoran Desert, Artsahkis (Armenians of Nagorno Karabagh) razed by the Azeris’ latest land grab, or even the freezer trucks parked in the US and EU containing the overflow of Covid-19 victims. Iran’s Evin prison may be a metaphor for the US’s Guantanamo prison or Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) borderland detention centers, or the Chinese internment camps for Uyghurs. The metaphors, alas, break the barriers of time and place.

Mona Seif—the Egyptian human rights activist known for her participation in dissident movements during and after the 2011 Egyptian revolution, as well as for her creative use of social media in campaigns—recently spoke with PBS, and was asked by journalist Nick Shifrin, in light of the failures in Egypt, “Was it worth it?” Was her tireless work to deconstruct the regime in Egypt worth the pain, the sacrifice, the prison time? Shifrin asked Seif if she’s lost hope, to which she replies, “I no longer function on hope.” Turning back to the US pre-election period, when Stacey Abrams, Democrat leader in Georgia, was asked if she has hope, like Seif, Abrams intimated that she doesn’t function on hope. Rather, she is determined.

Zahra’s Paradise, literally and allegorically, would be the final resting place for lost souls, lives cut mercilessly short, and revolutions halted if not for determination, if not for the “immutable law of nature” that Sarah Leah Whitson highlights. Spring is inextinguishable; it always returns. Seeds of determination, she says, have been planted. The planet will turn, the sun will reach noon, and shadows will recede. According to Punxsutawney Groundhog Club president, Jeff Lundy, Punxsutawney Phil promises that “one of the most beautiful and brightest springs” is forthcoming.

<