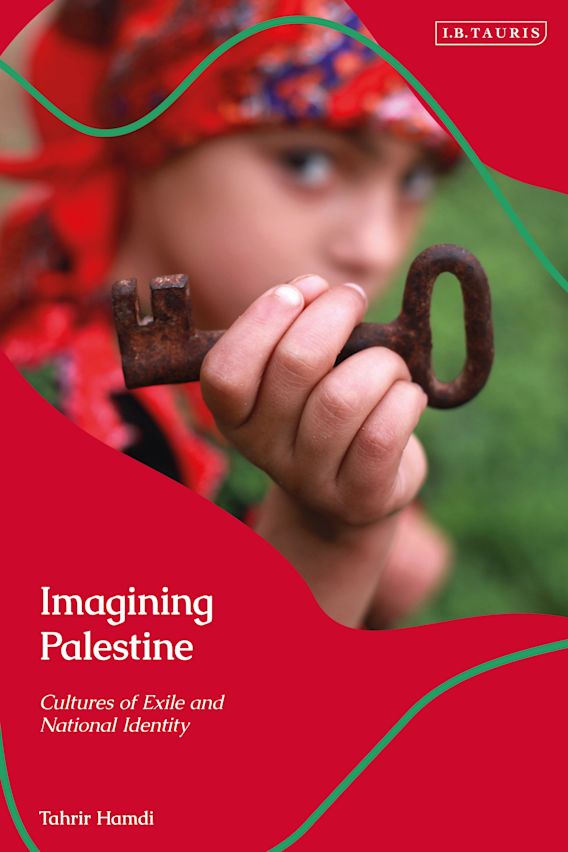

Imagining Palestine: Cultures of Exile and National Identity explores the ways that Palestinian intellectuals, artists, activists and ordinary citizens “imagine” their homeland, examining the works of key Palestinian and other thinkers and writers such as Edward Said, Ghassan Kanafani, Naji Al Ali, Mahmoud Darwish, Mourid Barghouti, Radwa Ashour, Suheir Hammad, and Susan Abulhawa.

Imagining Palestine: Cultures of Exile and National Identity, by Tahrir Hamdi

Bloomsbury 2023

ISBN 9781788313407

Ilan Pappé

True, This! —

Beneath the rule of men entirely great

The pen is mightier than the sword. Behold

The arch-enchanters wand! — itself is

nothing! — But taking sorcery from the

master-hand

To paralyse the Cæsars, and to strike

The loud earth breathless! — Take away the sword —

States can be saved without it!

So wrote Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1839, 41) in his play Richelieu; Or, the Conspiracy. Of course, the sword is still needed, and the pen has been replaced by the keyboard, but viewed historically, resistance through writing was done by pens, pencils, and typewriters, and even by graffiti on walls, cartoons, songs, poems, plays, and novels. Nowadays, the internet offers even more inventive ways of expression.

The “Theory of Palestine”

All of these audio, verbal, and visual expressions of the “pen” are part and parcel of the Palestinian resistance since its very inception, but rarely have they been articulated as a theory of resistance, one that helps to unpack the Palestinian experience in a way that feeds back into our understanding of other current struggles by indigenous people, life-seekers, workers, and anyone else victimized by the Global North’s economic, political, and moral order. Such a theorization is offered to us here by Tahrir Hamdi in her moving and thought- provoking book, Imagining Palestine.

This work is first and foremost a book on cultural resistance. As such, it requires an abstraction that cannot be taken for granted between two concepts: culture and cultural resistance.

In Culture and Imperialism, Edward Said commented that there are narrow and expanded definitions of culture. The narrow definition related to the aesthetic and literary assets of a society:

Culture is a concept that includes a refining and elevating element, each society’s reservoir of the best that has been known and thought, as Matthew Arnold put it in the 1860s. (Said 1993, xiv)

While the latter sees culture as the theatre of life:

In this second sense culture is a sort of theatre where various political and ideological causes engage one another. Far from being a placid realm of Apollonian gentility, culture can even be a battleground on which causes expose themselves to the light of day and contend with one another. (xiv)

In general, the approach to culture in Imagining Palestine, and by many of those analyzed by Tahrir Hamdi, is very much a reflection of Edward Said’s refusal to accept the separation of the cultural from the political, a ploy that Israel still uses today to pre-empt initiatives such as the cultural boycott, which is part of the BDS (Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions) campaign, by claiming that the state’s intellectuals, academics, and artists — or sports people for that matter — cannot be targets for being part of its politics of colonization. The hypocrisy of this Israeli and Western position was exposed fully last year: in the name of politics, one could boycott Russian sport, condemn Qatar during the World Cup for its human rights violations, but push away any attempt to apply the same principle to Israel and its role in the sporting world.

For Hamdi and many of those she surveys, the dichotomy is far less present, and the two are intertwined into what Hamdi refers to as a “theory of Palestine,” which means that not only does Palestinian cultural production involve both the narrow and wider Saidian definitions of culture, but it also provides abstraction of culture, resistance, and everything between them that can be applied elsewhere.

The second part of the theorization of Palestine is anchored on the abstraction of cultural resistance. Cultural resistance has become quite a common scholarly reference in cultural studies. As with so many such references, it has multiple meanings and usages (Kršić 2005). I find Roland Bleiker’s one of the most appealing when he conceptualizes dissent and cultural resistance as being “located in countless non-heroic practices that make up the realm of the everyday and its multiple connections with contemporary global life” (2000, 278). Cultural resistance underscores how various cultural practices are employed to contest and combat a dominant power, often constructing a different vision of the world in the process.

For Antonio Gramsci (1971, 229-39), power resides not only in institutions but also in the ways people make sense of their world; hegemony is a political and cultural process. Armed with culture instead of guns, one fights a different type of battle. Whereas traditional battles were “wars of maneuver,” frontal assaults that seized the state, cultural battles were “wars of position,” flanking maneuvers, commando raids, and infiltrations, staking out positions from which to attack and then reassemble civil society.

Several features of our time blur national and indigenous struggles in a way that might be less detrimental to the national project and beneficial to the community on the ground. As Stephen Duncombe (2002) remarks, with the immediacy of global media, the local becomes national and at the same time global. Stephen Duncombe offers another useful entry point on cultural projects: he sees cultural resistance as a space for developing tools for political action, a dress rehearsal for the actual political act or as a political action in and of itself, which operates by redefining politics.

Imagining Palestine is thus one of the most comprehensive representations of Palestinian cultural resistance. The analysis transcends the case study of Palestine and touches other people in the world still struggling against old and new settler-colonial projects, and who only lately discovered how relevant Palestine is for them, and how cultural, intersectional struggle may now be a crucial part of the way forward in the future.

Hamdi, however, does not employ a deductive approach: namely applying the abstraction and theorization of cultural resistance to the Palestine case study. This is an inductive research, where the case study leads to the more general discussion. This is a welcome approach, which I recommend to my postgraduate students who like to remain in the comfort zone of deductive analysis. The uniqueness and exceptional realities in Palestine (in particular, the imbalance between Israelis and Palestinians), create a dialectic which is Palestine: full of paradoxes and dichotomies that indeed call for a theory of Palestine alongside, and not instead of, a more conventional approach to its history and present conditions.

Late Style Resistance

Some of the people we meet in this book are not with us anymore. Whether writers, singers, poets, or artists, they underwent different stages in their struggle against the settler-colonial movement of Zionism and the apartheid state of Israel. Towards the end, whether consciously or unconsciously, and whether they died a natural death or were killed as martyrs in the struggle, they offer a very unique perspective in what is known as “Late Style,” which Hamdi focuses on in her early chapters in this fascinating book.

“Late Style” is an imagined or real sense of facing the end which, for instance in the case of Said, one of the many heroes of this book, led to a certain assertiveness about seeming paradoxes in his life and thought, which he learned to reconcile over the years. Said was constantly challenged for criticizing nationalism in general on the one hand, but remaining loyal to Palestinian nationalism, on the other. I will come back to the notion of “Late Style” when examining the exilic locations of many of the protagonists of this book.

Said is not the only one who navigates as a Palestinian between noble universal values and the existential challenges faced by Palestinians on the ground. In Imagining Palestine, Hamdi follows the way Palestinians and pro-Palestinians involved in cultural resistance reconcile various contradictions or seeming dichotomies in a similar way. That similar way is akin to a theorization of the struggle for Palestine, or indeed of Palestine itself as a concept, what Hamdi calls “theorizing Palestine.” This is a life-long process of resignation to the need to co-exist with unsolved paradoxes, a fluid situation that Said recognized in his own identity, as Hamdi reminds us when citing the opening sentence of the last paragraph of his autobiography Out of Place: “I occasionally experience myself as a cluster of flowing currents” (1999, 295).

As Imagining Palestine shows so poignantly, Palestinians who are involved in cultural activity of any sort, and those who support Palestine, are all grappling with dichotomies that are only overcome by a clear realization that culture and resistance go hand in hand when going through what Hamdi calls the “post-catastrophic condition” in which Palestinians exist. In fact, many Palestinians do not regard themselves as living in any post-reality, as they refer to this history and present time as the ongoing Nakba, namely the ongoing catastrophe, and at the same time see themselves in a constant struggle for survival, a kind of ongoing intifada (resistance).

Palestinians or people who are immersed in the struggle for Palestine out of solidarity and a sense of justice, are aware of the tantalizing shift between despair and hope, oppression and resistance, erasure and rediscovery of Palestine. If your only source of information is mainstream Western academia and media, you may miss the fact that since 1920, Palestinians have struggled individually and collectively for the liberation of their country day in and day out; they have faced daily attempts of dispossession. Even though almost the whole of historical Palestine has been taken over by the Zionist movement, and half of the Palestinians were ethnically cleansed, there is still a sizable presence of Palestinians in historical Palestine, and the struggle continues from within and without. It is an incredible story of resistance because of the power imbalance between Israel and the Palestinians. Israel is supported by a Western international coalition that, from its inception, has legitimized and legalized every stage of the dispossession of the Palestinians. This coalition provided Israel with economic, diplomatic, and military aid that made the Jewish state the most formidable regional power in the Middle East. The Palestinians were, and remain, without a state, a military, or an independent economy, and only count on the support of global civil society and that of very few states such as Cuba, Syria, and Iran, along with Bolivia and Venezuela (which do not have an impact as such on the balance of power on the ground).

So how, despite these almost impossible circumstances, is there an ongoing resistance? Why are so many of us still convinced that the struggle is not over, and justice will prevail? Hamdi takes us on a journey to one dimension of this struggle, the cultural one, which provides a very inspiring and moving answer to this riddle.

Theorizing an Actual Liberation

Theorizing an actual liberation struggle, nonetheless, is not just an act of abstraction. Seeking the middle ground between a discourse of contemplation and a conversation with the people themselves is quite a challenge since the language inspired by the works of Said, Bell Hooks, or Edward Soja, not to mention Gayatri Spivak, has its own rich vocabulary and phraseology different from the language used by those who are actually the object of such intellectual enterprises — namely the freedom fighters or the very people the intellectuals wish to represent and support.

Some of the intellectuals in the case of Palestine are freedom fighters themselves; hence, the dichotomy is much less acute. Thus, for instance, Ghassan Kanafani is treated rightly in this book as a theorist of liberation and at the same time a freedom fighter, and his cultural production is both a weapon in the overall resistance and a crucial contribution to the discussion of the link between culture and resistance.

Many lesser-known Palestinian artists are also freedom fighters, such as the young Palestinians who draw graffiti on the apartheid walls or wherever they can in public spaces, showing their commitment to the struggle. For many years, such wall paintings were regarded by scholars as the work of youth delinquency, but recent scholarship on this topic, in general, shows much more appreciation for the art of graffiti, and in this new view it represents a means to share values, ethics, and codes of behavior in the locations where, and the media through which, graffiti is produced.

The same is true of cartoonists, with some more famous than others, beginning, of course, with Naji al-Ali, who was a shahid (martyr) as much as anyone killed in the struggle for liberation. Cartoonists are featured in Hamdi’s book alongside poets who were freedom fighters in action as well as in writing, dating back to the resistance songs of Nuh Ibrahim, the poet of the 1936-39 Palestinian Revolution, through the poetry of 1948 Palestinians under military rule, all defined together in what Ghassan Kanafani called Adab al-Maqatil (resistance literature).

Exilic Resistance

Hamdi allocates much space to this discussion on the relevance of theorization to an actual liberation struggle. She identifies closely with intellectuals who refer us to marginal and third spaces as an ideal position from which they could contribute to the almost paradoxical idea of a practical theorization (not dissimilar to liberation theologies which in their own way grapple with similar challenges). The search for this navigation is the thread that connects an incredibly rich assortment of writers, poets, and artists, examined lovingly and movingly in this book — and one would be heartless not to share Tahrir’s admiration and affinity for those she writes about in this book.

Navigation is a place of exile. Readers of this book will discover — and anyone familiar with Palestinian intellectual activism recognizes — this is not merely a geographical exile. Many Palestinians in Palestine are in exile, and many of those in exile feel as though they are under colonization and occupation, as if they were still in Palestine.

The exilic space for those involved in cultural resistance is, first and foremost, an epistemological and intellectual space, a notion brilliantly explored by Said in several of his works. Abdul R. JanMohammed found for Said a special term, “the specular border intellectual” (1992). There are two border intellectuals according to Abdul R. JanMohammed: the syncretic and the specular. In its simplest form one may say that the former is an intellectual at home in two or more cultures, and thus busy fusing and combining hybrid influences. The latter is not at home with either, although he or she is quite familiar with them, and is thus preoccupied with the deconstruction and critique of both.

We may inject into this definition Said’s own typology of intellectuals: first, in the footsteps of Walter Benjamin, the preference for the watchdog of society over the articulator of its truisms; then the combination between the organic intellectual of Antonio Gramsci affiliated to a grass-root movement, such as nationalism, but nonetheless committed to the purest forms of freedoms of expression and thought, as proposed by Julien Benda (Said 1994, 183-4).

The centrality of “exile” as an epistemological construct is the product of time, and not only of principle. In his post-mortem text, Said focuses on the theme of “Late Style,” “the way in which the work of some great artists and writers acquires a new idiom towards the end of their lives — what I have come to think of as a late style” (Said 2004b). Said was aware he was coming to the end of his life, and this is why his own work was transforming not only idiomatically but also thematically. This is where the discussion of exile is so mature and ripe.

What the latter process achieves, as becomes clear in Said’s last interview with Charles Glass, is the maturation of his contrapuntal dialectical approach to harmonious and complementary affiliations and values (Said 2004a). He can tell Nubar Hovsepian that he takes a lot of luggage with him because he fears he will never return — a sad reminder of his 1948 experience — and yet he defines exiles like him, fortunate enough, unlike political exiles, to treat home as a temporary base which allows freedom of thought and spirit. As a Palestinian, exile, in the first instance, is traumatic; as a universalist intellectual, it is an asset. At the beginning of the 21st century, there was no need to apologize for or to reconcile this contradiction (Hovsepian 1992, 5).

But is it a closed circle? Has Said left us with a clear answer of how a society can be both wedded to nationalism and yet secure individual liberties and criticism? Whether from a Marxist or a liberal point of view, critics of nationalism produced a dire picture of it; whether they treated it as an ideology, a construct, or an interpretation of reality, they presented it as a reductionist mechanism of identity and interpretation that serves the ambitions of a few at the expense of the many. Said the refugee could not easily allow himself to join in the celebration of demythologizing nationalism. His Palestinianism, so to speak, had to coexist, uncomfortably, with his universalism. Time made this necessary coexistence an asset, not a liability, and this in fact was his political legacy for the future: Jews and Palestinians would have to reconcile to a similar existence as does the national intellectual in exile.

What is so brilliant about this book is that it links the human approach by so many of the Palestinians discussed here to the same paradoxical epistemological and moral questions: navigating between their universal values, unconditional commitment to the liberation of Palestine, and their particular mode of expression. Such navigation is at the heart of the “Theory of Palestine.”

What makes Hamdi — and Said for that matter — confident that they struck the right balance of making theory relevant is the fact that they are not overtheorizing, so as to make sure that theorization is based on experience, not just abstract contemplation. Theory for Hamdi, therefore, is not necessarily universal, but feeds back into the place where similar experiences are taking place.

Hamdi does not idealize the place of exile or margins. As seen from the poems of Mahmoud Darwish and Mourid Barghouti, it can be a dark place, what Barghouti refers to as ghurba, which is both absence and alienation, and at the same time a place of creativity. Exile on the margins can take place in a relatively comfortable space, such as Columbia University in New York, but also a very precarious and dangerous spot, such as a refugee camp in Lebanon. But in both locations, the prosecution of cultural knowledge becomes an invaluable contribution to the overall struggle for the liberation of Palestine.

Cultural Resistance for Our Times

In Imagining Palestine, a theorization of cultural resistance is inducted from the case study itself. In particular, it is the powerful poetry of Mahmoud Darwish that indicates the link between cultural resistance and actual resistance, and between abstract theorization and concrete experience. As Hamdi shows us, this is clear when one examines more profoundly Darwish’s metaphors, which fuse the personal and the political. When, for instance, the poet refers to Palestinians entering their private homes, he also alludes to their entry to their homeland, and this dual metaphoric representation appears in almost every stanza, story, and essay discussed in this book. It goes beyond metaphors as well to the whole attendance to aesthetics — the limited Saidian definition of culture is interlinked with political struggle: the form and the content have the same importance in the wish to be part of the overall resistance. Darwish clarified this when he stated: “no aesthetics outside my freedom.” A similar engagement is offered by the poet Mourid Barghouti when he wonders in his poetry whether one can oppose oppression with an army of metaphors.

This is a concern for Barghouti, as those involved in cultural resistance do not forget for a moment the other modes of resistance, in particular the armed struggle, and the daily, brave guerrilla warfare, which began in 1929 and continues today in what Hamdi calls eastern Palestine (namely the West Bank), and is enhanced by the resilience of the besieged people of the Gaza Strip. As Hamdi shows towards the end of her book, those involved in cultural resistance discussed other modes of resistance available for a liberation movement engaged in one of the longest anti-colonial struggles in the world. All the means are justified and discussed, sometimes ambiguously, as Hamdi points to the different but complementary approaches to armed struggle taken by Susan Abulhawa in Mornings in Jenin, compared to her other work, The Blue Between Sky and Water. In Mornings in Jenin, there is a fine discussion about the wish for non-violent resistance, and yet she is praising the armed resistance in other works. This clear navigation (so Saidian) between the principle universal positions, and the way they can be concretized under oppression, is part of the “Theory of Palestine.” Such navigation will continue to occupy those involved in cultural resistance, as seen with the various attempts to change the harrowing ending of Kanafani’s Men in the Sun. The helpless death of the men in a tanker, allegedly without any resistance, was not the ending one would find in the film adaptation or the transfer of the story to the year of 1982 by the late ‘48 Palestinian playwright and director Riad Massarweh. And this is why we met a jubilant Said at the Fatama Gate, between south Lebanon and Israel, hurling stones at the Israeli fence; the same Said who was inspired by the humanism of cosmopolitan Jews at the turn of 20th century Europe.

Cultural Unity and Political Disunity

Thus, cultural resistance is diverse, porous, and dynamic. But on the other hand, it is an antidote to the political disunity from which Palestinians suffer. The cultural resistance reveals unity of conscience as well as of memory. Its symbols are consensual as are its heroes and heroines. Whether it is Basel al-Araj, who wrote and taught about cultural resistance himself before being assassinated by the Israeli army, or Leila Khaled—long may she live. They are not heroes who necessarily defeated their enemies, but they defeated defeatism, which is one of the raison d’etre of the ongoing intifada. This rejection of defeatism enabled Palestinians to challenge the main objectives of the colonizer. As Hamdi reminds us, this was very accurately articulated by Frantz Fanon in The Wretched of the Earth: “Colonization is not satisfied merely with holding a people in its grip and emptying the native’s brain, but by a kind of perverted logic, it turns to the past of the oppressed people and distorts, disfigures and destroys it” (2004, 149). Moving from one mode of resistance, or from theory to praxis, and from culture to politics, and remaining in between both also applies to the challenge that the “Theory of Palestine” poses to different Palestinian geographical locations and the fragmented existence imposed on the Palestinians by the Israelis since 1948. Therefore, at the end of the book, it becomes clear why Hamdi devotes so much space to discussing whether exiled Palestine and occupied Palestine are the same space: you can be an exiled Palestinian inside historic Palestine, living less than a mile away from your original village that was colonized and Judaized in front of your eyes, or be in a refugee camp in the Gaza Strip or the West Bank, as well being either occupied or besieged. Whether you are in Sabra or Nazareth, you are denied the right of return, normal life, and liberation.

Thus, cultural resistance overcomes geographical distances, but it also challenges political dissent, since the works of artists unify the Palestinian existence and resistance. In this respect, the book could have also referred to the Palestinian academics who established in recent years a new area of study: Palestine studies. Among their unified contributions was a clear framing of what Palestine is, while politically it is debated by the world and Palestinian politicians. It is not only a whole geographic space; it is one that has always been a coherent geopolitical space. In her book, Hamdi illustrates, through ancient olive trees, the indigeneity of Palestine and its long history that since ancient times had only for a short period been partly ruled by Israelites in biblical times, and yet that is the one chapter in history around which the Zionist narrative and the claim for Palestine revolves.

The work of Palestinian historians, a group that is overlooked by Hamdi, has helped to produce a clearer sense of what Palestine means and what Israel does not. Through a committed chronology and genealogy, they showed that Palestine, as a coherent geopolitical unit, dates back to 3,000 BC. From that time onward, and for another 1,500 years, it was the land of the Canaanites. In around 1,500 BC, the land of Canaan fell under Egyptian rule, not for the last time in history, and then successfully under Philistine (1200-975), Israelite (1000-923), Phoenician (923-700), Assyrian (700-612), Babylonian (586-539), Persian (539-332), Macedonian (332-63), Roman (63BC-636CE), Arab (636- 1200), Crusade (1099-1291), Ayyubi (1187-1253), Mamluk (1253-1516), and Ottoman rules (1517-1917). Each rule divided the land administratively in ways that reflected its political culture and time. But, apart from the early Roman period and the early Arab period, when a vast population were moved out and in, the society remained—ethnically, culturally, and religiously—the same. Within what we recognize today, this society developed its own oneness and distinctive features.

In modern times, some of the above periods were manipulated and co-opted into a national, or colonialist, narrative to justify the takeover and conquest of the country. This historical chronology was used, or abused, by the Crusaders, and later European colonialists and the Zionist movement. The Zionists were different from the others, as they deemed — as did the powers that be when they emerged in 1882 — the historical reference was crucial for justifying their colonization of Palestine. They did it as part of what they termed “the Return” to or “Redemption” of the land, which was once ruled by Israelites; as the historical timeline above indicates, this is a reference to a mere century in a history of four millennia.

Away from the national narrative, we should say that Palestine as a geopolitical entity was a fluid concept since the rulers of the country quite often were the representatives of an empire, which disabled any local sovereignty from developing. The question of sovereignty began to be an issue — one that would inform the land’s history and conflict until today — once the Empires disappeared. The natural progress from such disintegration, almost everywhere in the world, was that the indigenous population took over. Ever since the emergence of the concept of nationalism, the identity of this historical revolution is clearer and more common. Where the vestiges of imperialism or colonialism refused to let go — such as in the case of white settler rule in northern and southern Africa — national wars of liberation lingered on. In places where the indigenous population was annihilated by the settlers’ communities, they became the new nation (as happened in the Americas and Australasia).

The takeover from the disintegrating empires succeeded in a longer process, though so many of the theoreticians of nationalism believe in social and cultural cohesiveness. The liberated land varied in structure and composition: some, having a heterogeneous ethnicity, religion, and culture, found it difficult to become a nation state, while others were fortunate, due to their relative homogeneity, although they had their share of economic polarity, social differentiation, and a constant struggle between modernity and tradition. A liberated Palestine would have belonged to the latter model, which for a while developed in Egypt and Tunisia, and less similar to the more troubled cases of Iraq and Lebanon.

These are the deeper and organic layers on which Palestinian culture rests, and this sense of continuity and attachment to the land is both theorized and illustrated through culture, not as an act of curiosity but as part of a struggle against erasure.

This uniformity in the cultural struggle explains the recent success in building intersectional and transnational cultural resistance. This new global context for the Palestinian cultural resistance is beautifully shown in Hamdi’s book by the various dialogues indigenous poets and writers had with their Palestinian counterparts. In this way, the massacre at Wounded Knee corresponds with the numerous massacres suffered by the Palestinians over the years. Intersectional solidarity also occurs between Arab poets and writers, as well as famous pop stars such as Roger Waters. Culture becomes enhanced resistance if it is part of a dialogue between people who are still struggling against oppression or show solidarity amongst each other. All living in what Steven Salaita calls the “geographies of pain” (2016, 111), Hamdi introduces these spaces through diverse literary and poetic sources.

In the end

Between framing the Palestinians as terrorists and Islamists to viewing them exclusively as victims, most of the people who know them, their history, their struggle, and determination, cannot but admire this nation without idealization, but just purely on common human and universal values.

Imagining Palestine teaches us something else about the Palestinians: notwithstanding their constant victimization by Zionism, they do not see themselves as victims but as people who still hope to win their battle for freedom and justice. Through the works of Palestinian literati, poets, writers, cartoonists, and cultural activists, the agency and resilience of the Palestinians shines through this book. This is not an attempt to idealize a group of very normal people but rather to show how humane the Palestinian struggle for normality is. And there is a good chance that this basic but noble human impulse will direct Palestine in its post-colonial era, when it arrives. In more ways than one, this book chronicles the story of the Palestinian cultural resistance and at the same time becomes part of this resistance.

Notes

• Bleiker, Roland. 2000. Popular Dissent, Human Agency and Global Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

• Bulwer-Lytton, Edward. (1839) 1996. Richelieu; Or, the Conspiracy. Philadelphia: The Penn Publishing Company.

• Duncombe, Stephen. 2002. “Introduction.” In Cultural Resistance Reader, edited by Stephen Duncombe, 1–16. London: Verso.

• Fanon, Frantz. 2004. The Wretched of the Earth. Translated by Richard Philcox. New York: Grove Press.

• Gramsci, Antonio. 1971. Prison Notebooks. Edited by Quentin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith. New York: International.

• Hovsepian, Nubar. 1992. “Connections with Palestine.” In Edward Said: A Critical Reader, edited by Michael Sprinker, 5-18. Oxford: Blackwell.

• Kršić, Dejan. 2005. “After Brecht.” In The Design of Dissent: Socially and Politically Driven Graphics, edited by Milton Glazer and Mirko Ilic. Gloucester: Rockport Publishers.

• JanMohammed, Abdul R. 1992. “Worldliness-without-World, Homelessness-as-Home: Toward a Definition of the Specular Border Intellectual.” In Edward Said: A Critical Reader, edited by Michael Sprinker, 96-120. Oxford : Blackwell.

• Said, Edward W. 2004a. “Edward Said: The Last Interview.” Interview by Charles Glass, directed by Mike Dibb, and produced by D.D. Guttenplan. Icarus Films. Video.

— 2004b. “Thoughts About Late Style.” London Review of Books, 26 (15), 5 August.

— 1999. Out of Place: A Memoir. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

— 1994. Representations of the Intellectual. New York: Pantheon.

— 1993. Culture and Imperialism. New York: Vintage Books.

• Salaita, Steven. 2016. Inter/Nationalism: Decolonizing Native America and Palestine. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ilan Pappe’s review of Imagining Palestine first appeared in Janus Unbound: Journal of Critical Studies, vol. II, no. II, 2023, published by the Memorial University of Newfoundland, and appears here by arrangement with the author.