Past Disquiet comes at a crucial time, when solidarity with Palestinian lives and culture is in the daily news, but often controversial due to the competing hasbara and Palestinian narratives. The curators of this exhibition have stitched together transnational histories, bound by solidarity, whose connections had been for the most part, lost. Further, it maps networks of artists who were the heralds of political change, who believed that art should be at the heart of everyday life (in streets, schools, and public sites), emancipated from class privilege. It also maps artist networks’ connections to militants who believed that political change is impossible to imagine without artists.

Rasha Salti and Kristine Khouri

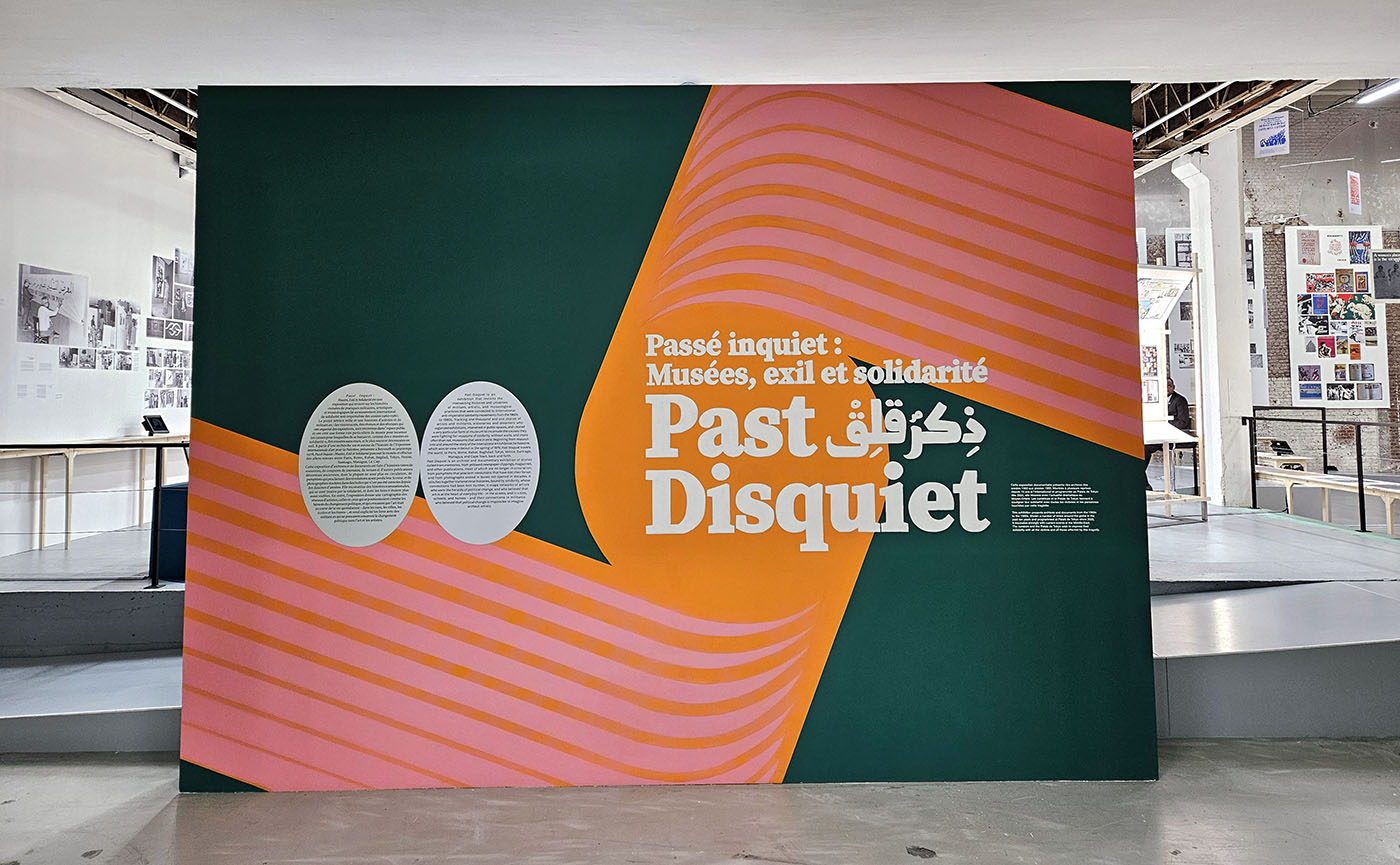

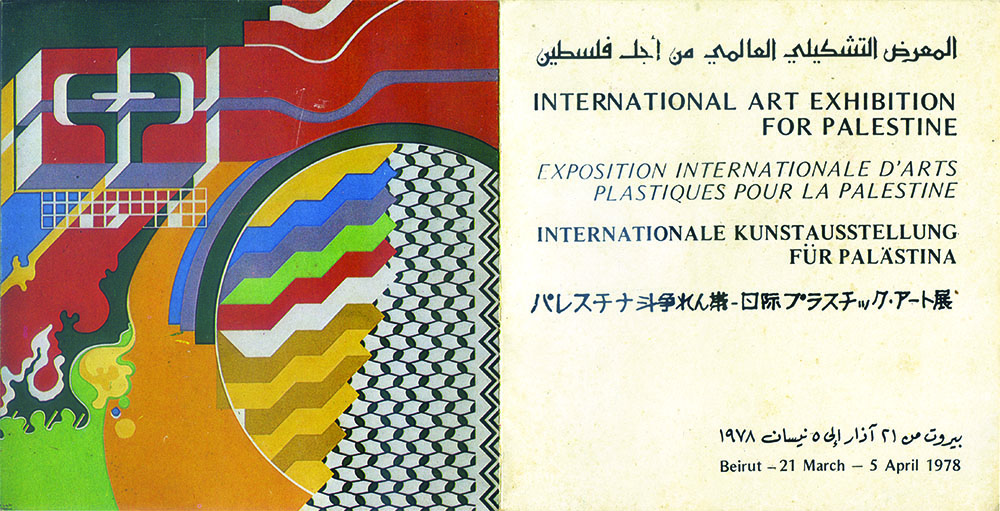

Past Disquiet is an archival and documentary exhibition that revisits the intersecting histories and universes of militant, artistic, and museological practices that were connected to tricontinental, anti-imperialist solidarity movements between the 1960s and the 1980s. Beginning from research into and around the story of the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, Past Disquiet tracks a thousand and one stories of artists, militants, visionaries, and dreamers who organized exhibitions, intervened in public spaces, and created a very particular form of museum to incarnate the causes they were fighting for, museums of solidarity, without walls, and more often than not, museums that were in exile.

The exhibition consists largely of stories culled from memories, from yellowed newspaper clippings, magazines, and other publications, most of which long stopped being in circulation; from pamphlets that proclaimed revolutions that have lost their fervor; and from photographs stored in boxes not opened in decades.

Past Disquiet stitches together transnational histories, bound by solidarity, whose connections had been for the most part, lost. Further, it maps networks of artists who were the heralds of political change, who believed that art should be at the heart of everyday life (in streets, schools, and public sites), emancipated from class privilege. It also maps artist networks’ connections to militants who believed that political change is impossible to imagine without artists. In the course of our protracted research, several maps emerged, of political events, upheavals, revolutions and artist actions, exhibitions. The cartography of connections reveals a geography that challenges the canons of the history of art in the second half of the twentieth century.

Early in the research process, we encountered the notions of the museum-in-exile and the museum in solidarity. Consequently, we dedicated considerable effort to understanding the origin of these two notions, and their mechanisms, by studying the traces of four collections of art whose histories had significant intersections. These are:

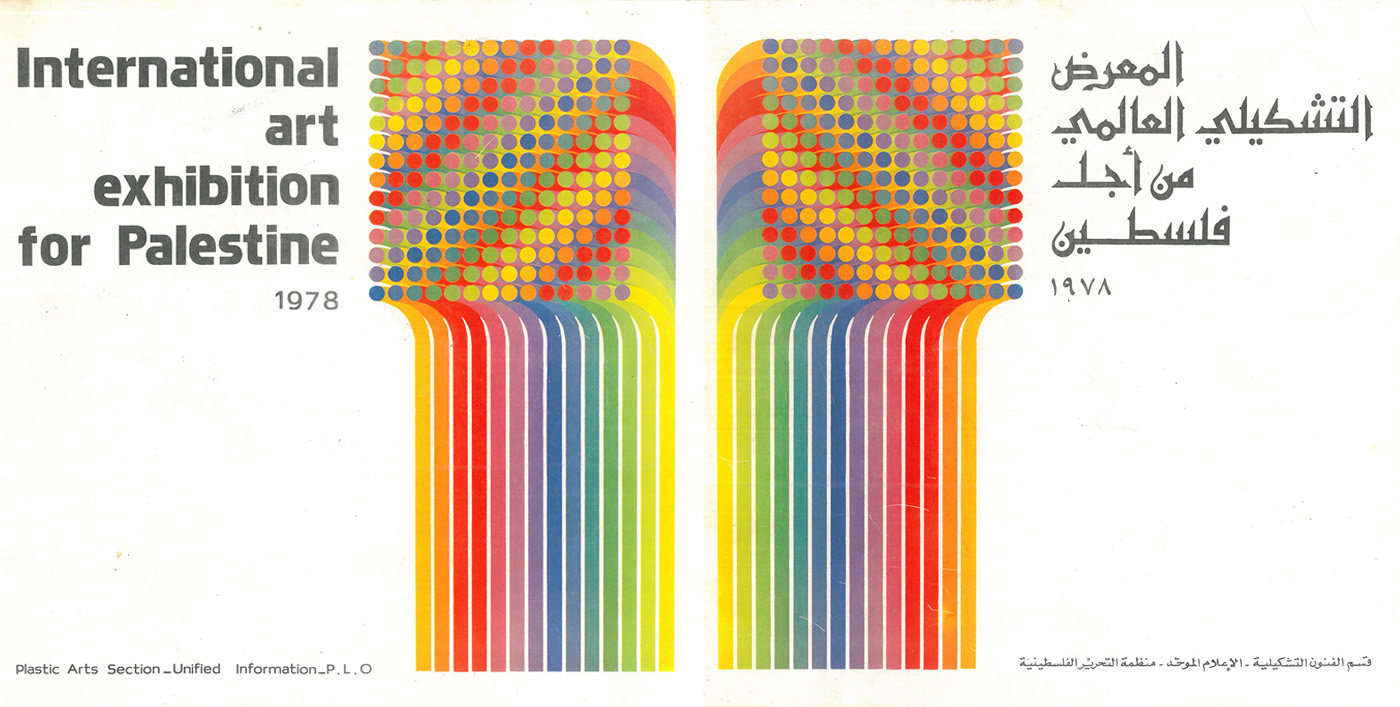

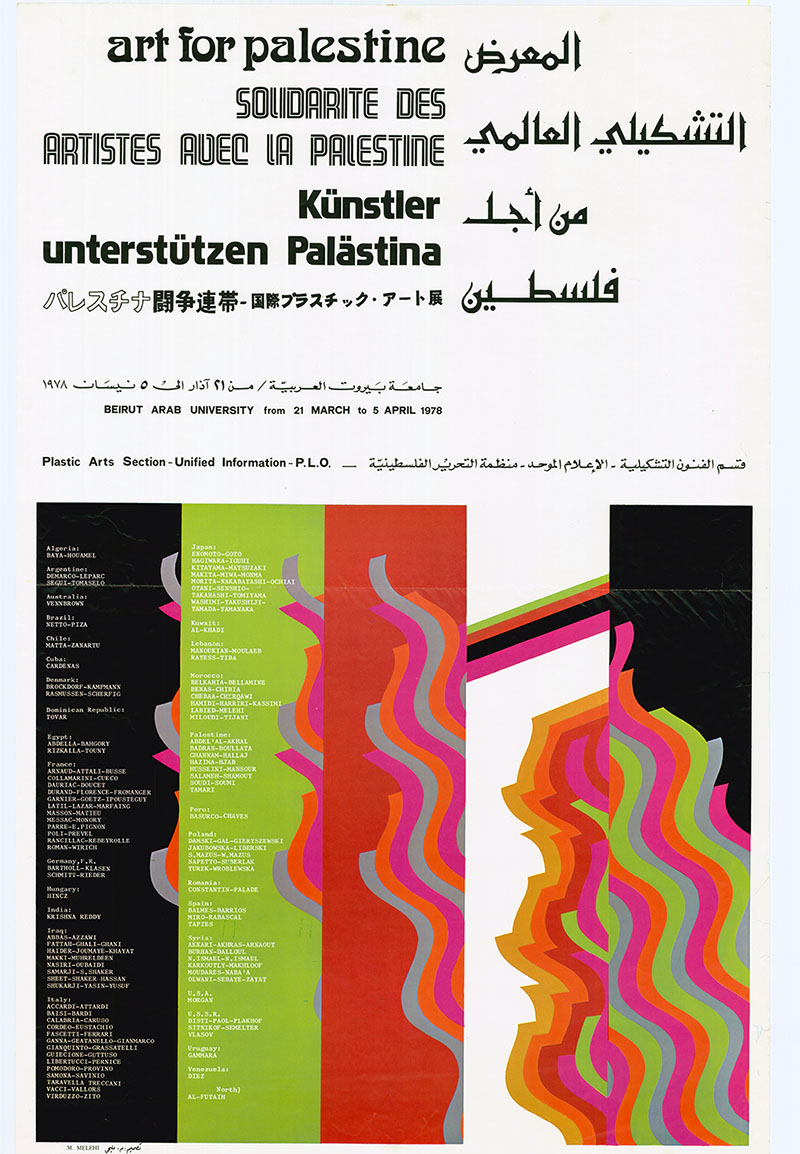

- the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, which was presented in Beirut in 1978;

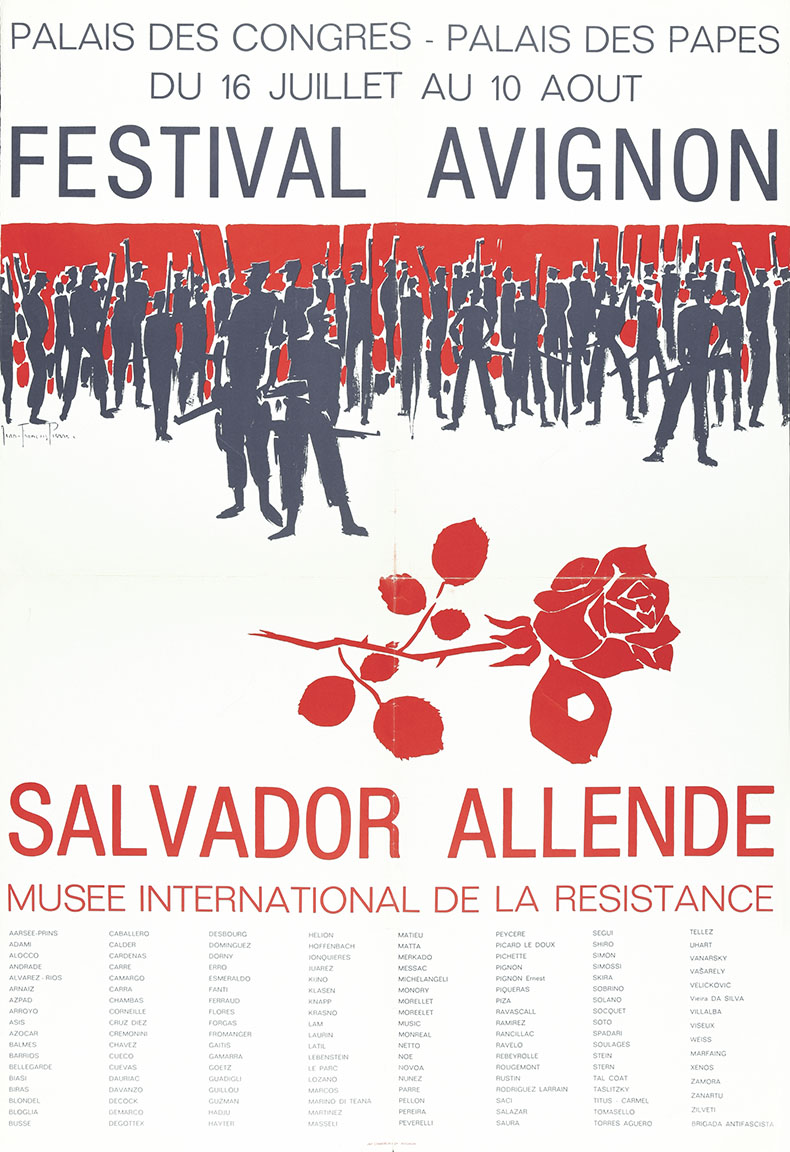

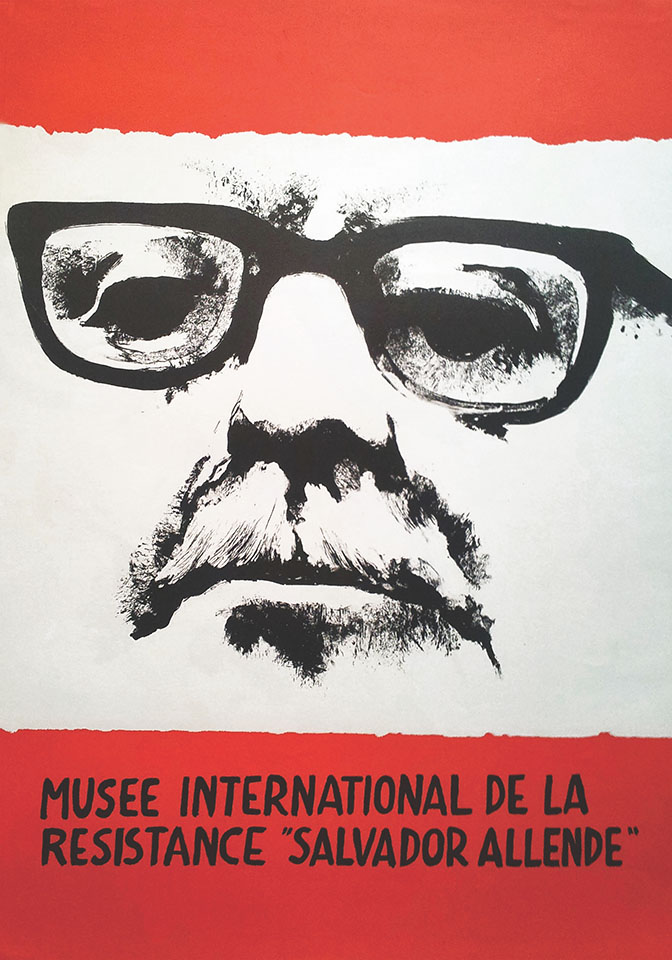

- the Museo Internacional de la Resistencia Salvador Allende (MIRSA), which was organized by Chilean exiles and their supporters after the 1973 coup d’état in Chile, as well as its earlier incarnation, the Museo de la Solidaridad, which was in existence from 1971 to 1973;

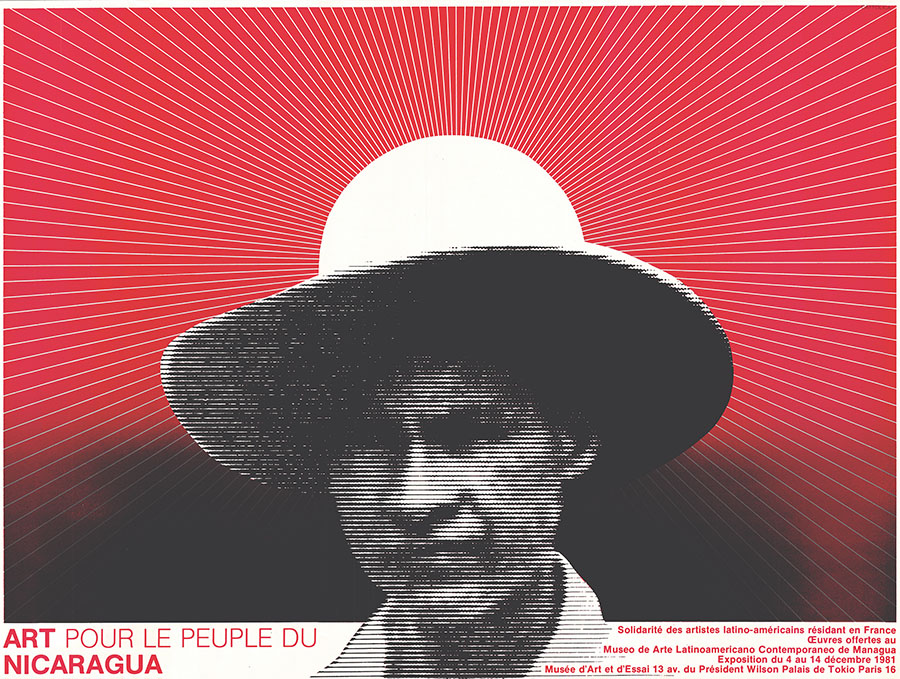

- the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano en Solidaridad con Nicaragua prompted by the first Sandinista government;

- and the Art Contre/Against Apartheid collection, which toured internationally in the years leading up to the fall of the apartheid regime in South Africa.

A museum in solidarity is a collection of artworks, donated by artists, their gift being a political gesture intended to demonstrate support for a movement of national liberation, or a struggle for justice and equality. Museum-in-exile is often the form they take — living outside of the country or cause they are supporting, in exile, and touring, until it can return or go “home.” Solidarity collections are important models of museology that have been almost entirely marginalized in the annals of art history and museum studies. These collections are emancipated from the systems of power and patronage to which museums are usually beholden, they are neither symbols of wealth accrued through the exploitation of human beings or natural resources, nor are they legacies of colonialism. They represent a thoroughly subversive interpretation of museums; and their collections are donated in the name of peoples, not governments.

On Museums and the Preservation of Cultural Heritage

Museums in Exile—MO.CO’s show for Chile, Sarajevo & Palestine

One version of the genesis story of the International Art Exhibition for Palestine links it directly to the MIRSA. At a celebration organized by Politique Hebdo, Ezzedine Kalak, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) representative in Paris, met exiled Chilean artists who were involved in the administration of the MIRSA, and this encounter inspired him to pursue a similar initiative for Palestine. Two other solidarity collections were also inspired by — and had strong connections to — the MIRSA. In solidarity with the people of Nicaragua after the success of the Sandinista revolution, the Museum of Latin American Art in Solidarity with Nicaragua was organized by Ernesto Cardenal (at the time the Nicaraguan minister of culture) and Chilean curator Carmen Waugh, who had played a significant role in creating the MIRSA while she was in exile. Waugh went on to become the director of the Museum of Solidarity with Salvador Allende (MSSA), its final and current iteration after democracy was restored in Chile. In that same year, artists Ernest Pignon-Ernest (France) and Antonio Saura (Spain) initiated in 1981, the Artists of the World Against Apartheid Committee, which assembled the Art Contre/Against Apartheid collection and toured it to almost forty cities around the world between 1983 and 1990. Both initiatives include works donated by artists who also contributed to the MIRSA collection.

Along with their core idea, these four museums-in-exile demonstrate notable overlaps in terms of the artists who participated, and the people responsible for their organization. Amid this worldwide mobilization of prominent voices to encourage and lend support to international solidarity, the impact of the MIRSA initiative, in particular, led to reverberations around the world, whose effects are relevant to this day.

Our inquest began with research into the 1978 International Art Exhibition for Palestine. We came across the catalog of the exhibition in the library of an art gallery in Beirut and were intrigued by its scale and scope: approximately two-hundred works were donated by almost two-hundred artists from thirty countries. The main text of the catalog stated that these artworks were intended as the seed collection for a future museum for Palestine. Organized by the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) through the Plastic Arts Section of its Office of Unified Information, the exhibition opened in the basement hall of the Beirut Arab University on March 21, 1978. The director of the Plastic Arts Section was Mona Saudi.

And yet, the exhibition is not mentioned in any local, regional, or international art-historical accounts; neither is there any reference to it in exhibition histories.

On March 14, 1978, exactly one week prior to the exhibition opening, Israel invaded Lebanon, advancing as far north as the Litani river and the outskirts of the city of Tyre to stop PLO commando incursions launched from the southern Lebanese border. The incursion lasted a week and concluded with an UN-brokered truce, and the deployment of UN-sponsored peacekeeping forces to oversee the implementation of the accord. Despite grave security concerns, Yasser Arafat, attended the exhibition opening, accompanied by the PLO’s highest-ranking cadres. In addition to Beirut’s intelligentsia, visitors included rank-and-file fighters, diplomats, journalists, and a dozen international artists, as well as the general public. In an interview recorded in Ramallah, Ahmed Abdul-Rahman, the head of the PLO’s Office of Unified Information at the time, underlines the importance of inviting artists to witness firsthand the reality of the struggle. Claude Lazar attended the opening in Beirut, as did Gontran Guanaes Netto (Brazil), Bruno Caruso (Italy), Paolo Ganna (Italy), and Mohamed Melehi (Morocco).

In 1982, the Israeli military advanced into Beirut again, holding the city under siege with the objective of forcing the PLO to quit Lebanon. The building where the collection of artworks had been stored was shelled, along with the Office of Unified Information, which housed the Plastic Arts Section and the exhibition’s paper trail. All that remained of the story of the International Art Exhibition for Palestine were the memories of those who made it happen and who visited it.

The International Art Exhibition for Palestine was certainly the PLO’s most ambitious endeavor, but it was not the only art exhibition it organized. The PLO’s leadership needed a means to communicate with its own constituency, which was scattered across neighboring territories in refugee camps and cities.

A second challenge was to communicate to the world the legitimacy of the Palestinian cause and to mobilize support for the struggle for emancipation. The most effective means to counter the traumatic dispersal of Palestinians was in safeguarding their sense of peoplehood through culture and the arts. If houses were lost, the poetic record of having had a home would remain alive; if the land was far removed from sight, its depiction would make it visible in myriad forms; if citizenship was denied, then the indignity that Palestinians endured was vanquished.

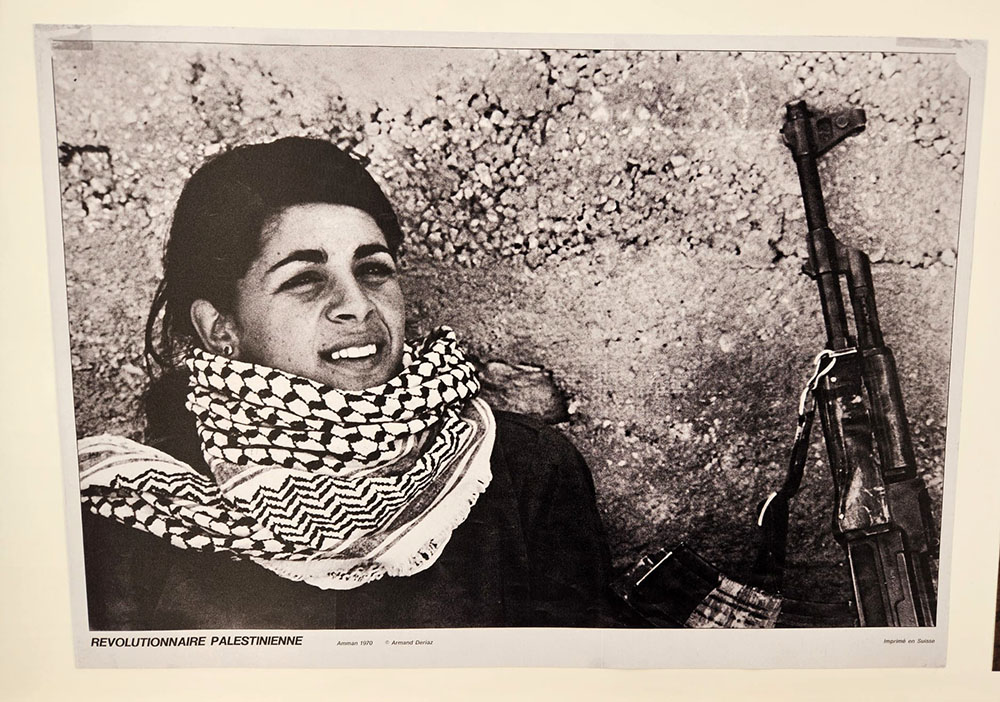

In the hands of artists, poets, filmmakers, musicians, and writers, the representation of Palestinians transformed them from hapless refugees living on handouts, to dignified, steadfast freedom fighters who had taken charge of their own destiny.

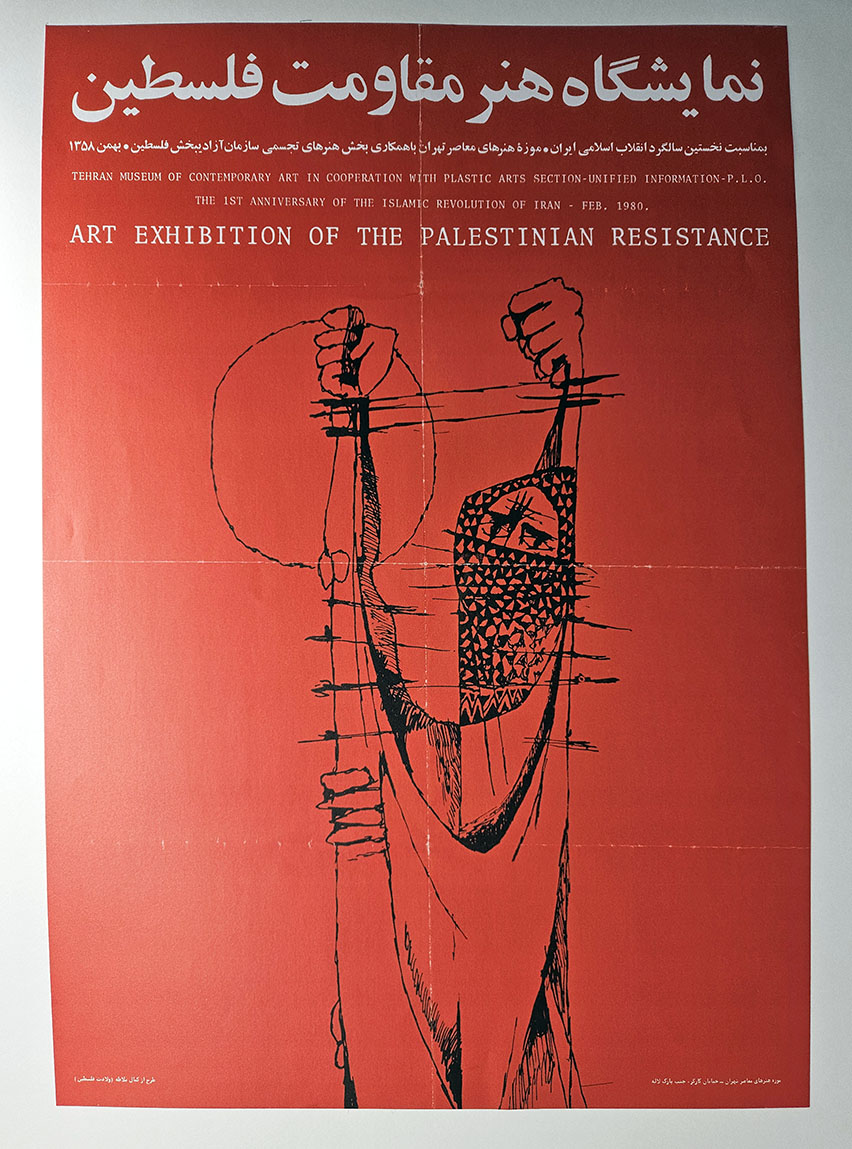

Both the Plastic Arts Section and the Department of Arts and National Culture (established in 1965) were mandated to commission, fund, and promote the production of posters, art, film, theater, dance, music, and publications; to preserve folklore and cultural traditions; and to galvanize support for the Palestinian struggle internationally, in the arena of art and culture. Exhibitions of traditional folk dress and crafts toured Europe between 1978 and 1980 to showcase the nation’s heritage. The PLO, and in particular its Plastic Arts Section, reproduced artwork on posters, postcards, calendars, and holiday cards that were circulated widely; it also organized exhibitions and provided support to artists. Posters were the foremost tool for the dissemination of image and narrative: they were lightweight, relatively inexpensive, and quick to produce, and could reach across social classes, cities, and countries.

The PLO was only recognized as the official and legitimate representative body of Palestinians at the UN General Assembly in 1974. However, with the help of the Arab League, the organization lobbied, one country at a time, to establish offices to represent Palestine that functioned like makeshift embassies, to manage the affairs of Palestinians in the countries in question, as well as to mobilize support for the Palestinian cause. The first generation of representatives was culled from refugee camps and the Palestinian diaspora, their political imaginaries and aspirations informed by the lived experience of indignity and the revolutionary emancipatory fervor that swept the region (Algeria, Egypt, Iraq, and Sudan) and the world (Chile, Cuba, and Vietnam). Some PLO representatives — for example, Fathi Abdul-Hamid (posted in Tokyo), Mahmoud al-Hamshari (Paris), Ezzeddine Kalak (Paris), Naïm Khader (Brussels), Wajih Qasem (Rabat), and Wael Zuwaiter (Rome) — operated with the conviction that mobilizing support for the Palestinian cause had to involve thorough, patient, and creative engagement with grassroots associations, unions, syndicates, and collectives of students, workers, and artists. In the countries where they were posted, they inspired artists and intellectuals to see in Palestine a mirror of the world’s injustice. They invited them to produce posters, exhibitions, conferences, and publications. In the GDR and Japan, they also facilitated collaborations between artists’ unions.

According to the catalog of the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, the greatest numbers of participating artists hailed from France, Italy, Japan, Iraq and Poland. The involvement of Ezzeddine Kalak who was assassinated in Paris several months after the opening of the International Art Exhibition for Palestine, was pivotal. He developed strong friendships with some members of the Association de la Jeune Peinture, particularly Claude Lazar. Many of the French artists who donated artworks to the International Art Exhibition for Palestine belonged to the anti-establishment, artist-run Association de la Jeune Peinture, which gathered militant artist collectives, radicalized after the upheavals of May 1968.

Formed in Paris in 1950, and officially established in 1953, the Salon de la Jeune Peinture was a singular event, created by artists and for artists, entirely free of the direct or indirect intervention of galleries and the market, in response to the scarcity of opportunities for artists, emerging or otherwise, to exhibit their work. The Association de la Jeune Peinture’s main resource was annual membership fees, its organizational structure included a general assembly that elected a committee to oversee its salon every year. The committee was in turn mandated to select artworks.

In 1968, the Jeune Peinture dedicated the salon to the victory of the Vietnamese people, named it Salle rouge pour le Vietnam, and held exhibitions in factories. In 1969 and 1970, the Salon’s theme was Police et culture, a multitude of artist collectives exhibited collective work, marginalizing contributions by individual artists. The Salons of 1971 and 1972 engaged with the social and political crises in France exhibiting exclusively collectively made works. By 1972, the salon had become an eminently political platform that hosted a range of artists’ collectives mobilized around local and international issues, among them the Palestinian struggle, the feminist struggle, workers’ rights, and environmental issues.

Fathi Abdul-Hamid, the PLO’s representative in Japan (1977-1983) was in close contact with the Japan Asian African Latin American Artists Association (JAALA) and its founder, Haryu Ichiro, a radical art critic, theorist, and writer. On the occasion of the international biennial exhibition The Third World and Us at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum in July 1978, JAALA invited Palestinian artists to present work alongside Japanese artists. In addition to hosting exhibitions, the association organized conferences raising anti-war, anti-nuclear, and anti-imperialist consciousness, in which artists and intellectuals from countries such as Palestine, South Korea, and Thailand were involved. The collection in solidarity with Palestine had its first tour in Japan, where one hundred works were selected and exhibited in July 1978.

Many of the Italian artists who donated artworks to the International Art Exhibition for Palestine belonged to the anti-establishment, artist collectives that gravitated around the Italian Communist Party and participated in the annual Festa de l’Unità throughout the 1970s. Some were connected through artist collectives, particularly L’Alzaia. Its members began to collaborate informally in 1968, but the collective was formally founded in 1971 by Ennio Calabria, Paolo Ganna and several others. Ennio Calabria had become a close friend of Wael Zwaiter, a Palestinian translator and the PLO representative in Rome (assassinated by members of the Mossad in October 1972). The collective rented a space on via Minerva, in the historic center of Rome, where they hosted exhibitions, performances, and workshops, and produced posters and serigraphic prints. The collective engaged with issues of social justice, fair access to public housing, urban development in Rome, and organized direct interventions in public spaces. The collective also extended its support for international causes. In December 1973, for example, L’Alzaia organized an exhibition in solidarity with the Chilean people. A year earlier, it had presented exhibitions including a display of documents denouncing the military dictatorship in Greece, a collection of silkscreen prints from Cuba, and a series of posters of the Palestinian struggle. The artists from L’Alzaia participated in the 1973 Rome Quadriennale; and the Salon de la Jeune Peinture in 1974.

L’Arcicoda was another collective, its member artists were based in Tuscany, in and around the town of San Giovanni Valdarno in 1973. L’Arcicoda was cemented around the conviction that art should be produced against and outside the gallery system and the market. The collective organized exhibitions and interventions in independent and public spaces, looking for direct, anti-elitist contact with the public. They made serigraphic and lithographic prints and posters around local and international issues.

In 1976, the siege (88 days) and massacre of Palestinian refugees in the Tal al-Zaatar camp on the outskirts of Beirut made headlines in the international media, but this was not sufficient to impose pressure to relieve the civilians caught in the siege. In solidarity, PLO representatives and pro-Palestinian militants mobilized protests, collected donations, and staged events. An impressive number of posters were produced to raise consciousness. L’Arcicoda collaborated with the Collectif Palestine (a.k.a. the Collectif de peintres des pays arabes) and other groups staging exhibitions and painting interventions in public squares in several towns in Tuscany to inspire solidarity with the people under siege in the Tal al-Zaatar camp. The most memorable took place at the Piazza Ferretto in Mestre, on September 7, 1976, during the 37th Venice Biennale. Luigi Nono performed live music and Rachid Koraïchi painted the words Tal al-Zaatar in Arabic when the canvas was covered.

Artist unions represented another nexus of mobilization.

In the Arab world, most unions and artists’ associations were formed in the 1960s and early 1970s out of a basic necessity to defend artists’ rights, create a support structure for the promotion and dissemination of their work, and solidify existing organic bonds of fraternity across the Arab region. The Union of Palestinian Artists (UPA), founded in 1973 in Lebanon, established an exhibition space known as Dar al-Karameh, which presented the work of Palestinian and international artists. The UPA also established protocols of collaboration with international artists’ unions in the German Democratic Republic (GDR), Vietnam, and Japan. These collaborations included artist exchange programs and touring exhibitions.

The Israeli administrators often shut down the exhibitions during the opening, or a few days afterwards. They had imposed strict rules that forbade the use of Palestinian national symbols, including the Palestinian flag, and the use of its colors, namely red, green and black in a single composition (and the reason watermelons became a subversive symbol in Palestinian art).

Inspired by the Union of Palestinian Artists established by artists who were refugees in Lebanon, Syria and Jordan, Palestinian artists living in the West Bank and Gaza, under Israeli occupation since 1967, undertook the step to establish a framework for collective action. Although the Israeli military administrator refused their request to form an association, they nonetheless created the League of Palestinian Artists officiously. The League organized several exhibitions that toured in the cities and towns of the West Bank, and in parallel artists of the League chapter in Gaza as well. The Israeli administrators often shut down the exhibitions during the opening, or a few days afterwards. They had imposed strict rules that forbade the use of Palestinian national symbols, including the Palestinian flag, and the use of its colors, namely red, green and black in a single composition (and the reason watermelons became a subversive symbol in Palestinian art).

In 1981, the Palestinian Red Crescent Society (a counterpart to the Red Cross Society), founded by the communist militant and intellectual Haidar Abdel-Shafi, hosted an exhibition by the League that was presented in several cities in Gaza, the West Bank as well as Israel. That exhibition became the official de facto recognition of the League, which was able to register as a union under the umbrella of the existing Union of Engineers.

The establishment of the Union of Arab Artists (UAA) formalized networking, exchange, and cooperation among artists at a regional level. The idea of such a union had been discussed at the First Arab Conference on Fine Arts in Damascus in 1971 and was formally constituted in 1972 at the First Arab Festival of National Plastic Arts in Damascus. Ismail Shammout president of the UPA, was voted President of UAA, a role he held from 1971 until 1977. Two editions of the Arab Biennial, which were held in Baghdad in 1974 and in Rabat in 1976, were organized by the UAA, and foregrounded the dedication of Arab artists to the Palestinian struggle.

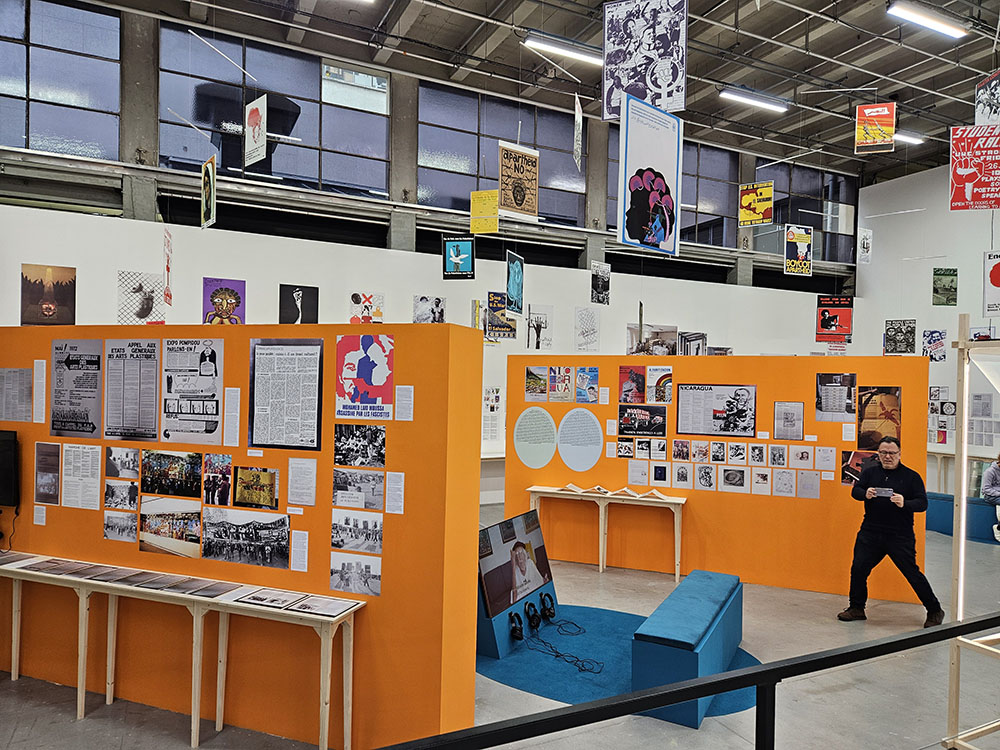

Past Disquiet is an exhibition of stories collected over ten years of research. The past we refer to is recent, and a number of its protagonists are still alive. Nevertheless, for the most part, these stories narrate undocumented chapters in the history of modern and contemporary art that chronicle the actions of groups of artists to engage with political change. Throughout the various editions of the exhibition, we always asked ourselves the significance of reviving images and stories decades in their aftermath — after the Pinochet dictatorship was defeated, after South Africa ended Apartheid, and after the PLO had created the Palestinian National Authority. This aftermath has its own set of problematics, unresolved internal conflicts, and scars that have not yet healed, but if we zoom out to a wider perspective, ours is a time when utopias have lapsed and struggles for liberation have not met their promise to the fullest, yet. Some might even argue ours is the time in the aftermath of defeat. The histories we have unearthed have scant, dispersed archival traces, few of which still exist in institutions. And some archives have been destroyed. The raw material of the exhibition consists of interviews, archival documents, images and moving image footage. When we interviewed artists and militants, we were aware that we were in fact asking them to harken back to historical moments when hope and aspirations were still vibrant. The images (photographs, posters, artworks) and documents had “survived,” while the political, discursive and ideological framework in which they had produced had subsided. This kind of time travel has its trappings, the most obvious being the lure of nostalgia, thus, it was necessary to look at the images historically.

Circling back to questions about our intentions, the attribute “disquiet” in the title of the exhibition, holds, at least in part, an answer. It points to the unsettled nature of this past, to its wounds, deceptions, betrayals, and yet at the same time, it points to its refusal to lay quietly, to be folded into silence, or to be dismissed and boxed away. “Disquiet” portended to our immunity against indulging nostalgia. The exhibition is an invitation for a reckoning of, and reflection on, the failures and spoils of such impressive mobilizations of imagination, of creativity and of audacious action.

One the chief motivations that have carried us throughout these years is our desire to make these histories visible, tangible and transmit a memory all too easily eluded. Past Disquiet is a vibrant and tirelessly proliferating archive intended to be shared and appropriated. The second motivation is to decenter art historical narratives of the second half of the past century, and to complicate narratives of the East-West divide during Cold War, by shifting the paradigm from which we revisit artistic practices, namely from the perspective of the agents and actors from the (so-called) south, and from the perspective of solidarity.

A powerful, potent notion that today reclaims streets and headlines, “solidarity” manifests in myriad actions, symbols and expressions across our exhibition and is in constant regeneration and reinvention. What we want to offer is what the images and documents show: artists from Botswana, Japan, Morocco, Cuba, France and Chile resisted against oppression and indignity and together they dreamt another, better world in resonant ways across the world. They dislodged art from its “conventional” sites and relocated it to political and social life.

The gender disparity visible in the documents and archives is in the spirit of its time. Women are present, and although they played key roles, save for a few exceptions, they appear in “the second row” of photographs, testimonies and acknowledgements. Our mission was to reclaim the overdue recognition they are owed. Women such as Carmen Waugh, Dore Ashton, Lucy Lippard, Gracia Barrios and Maeda Rae, to give a few examples. In the decades that our research spans, transnational struggles intersected with feminist struggles but the complicity and shared sentiments of solidarity were far more at the level of discourse (and lip service), patriarchy and misogyny still wielded mainstream currency.

Our research methodology was close to detective work, replete with fortuitous encounters, providential accidents, surprising coincidences, and epiphanies. We went in circles, and back and forth, allowing stories and characters to lead us. When we present the outcome of the research in the form of an exhibition, the scenography partially re-enacts our forensic process. A linear dramaturgy, with a clear beginning, middle, and end, would have cheated the complexity of the histories unveiled, and thwarted visitors from threading narratives for themselves. The logic of the scenography grounds prominently, like tree trunks, the stories of the four solidarity collections or museums-in-exile in the rooms, and around them radiate and expand, horizontally and vertically, stories that lead to other stories and more stories, to incarnate more richly the historical and cultural cosmogonies in which they emerged and shone. The core of the rhizomatic meshwork is located at the end of each of the two rooms, and bridges between them. It is made of the stories of artist collectives, associations and unions that formed the soil from which the four initiatives stem.

1 comment