MO.CO, Montpellier’s contemporary art museum, presented “Museums in Exile” through February 5, 2023.

Jordan Elgrably

Jordan Elgrably

When war envelops a country, as it has Ukraine this year, and did in Syria a decade ago, both people and their culture come under attack. The very definition of genocide, according to the UN’s 1946 resolution against it, speaks of “great losses to humanity in the form of cultural and other contributions.”

Montpellier’s newest museum, the MO.CO Montpellier Contemporain, has curated a tremendous exhibition that commemorates the people of Chile, Sarajevo and Palestine, who have all endured hardships that include war, sieges, mass destruction of property, arbitrary arrests without habeas corpus, forced disappearances, mass graves, and exile.

The beauty of these three “museums in exile” is that the bulk of their collections consist of artwork donated by world artists sympathetic to the plight of people under attack. They are as such solidarity museums. In fact, the exhibition might have well been titled “Artists Against War,” for the donated work forms an eloquent argument against violence itself.

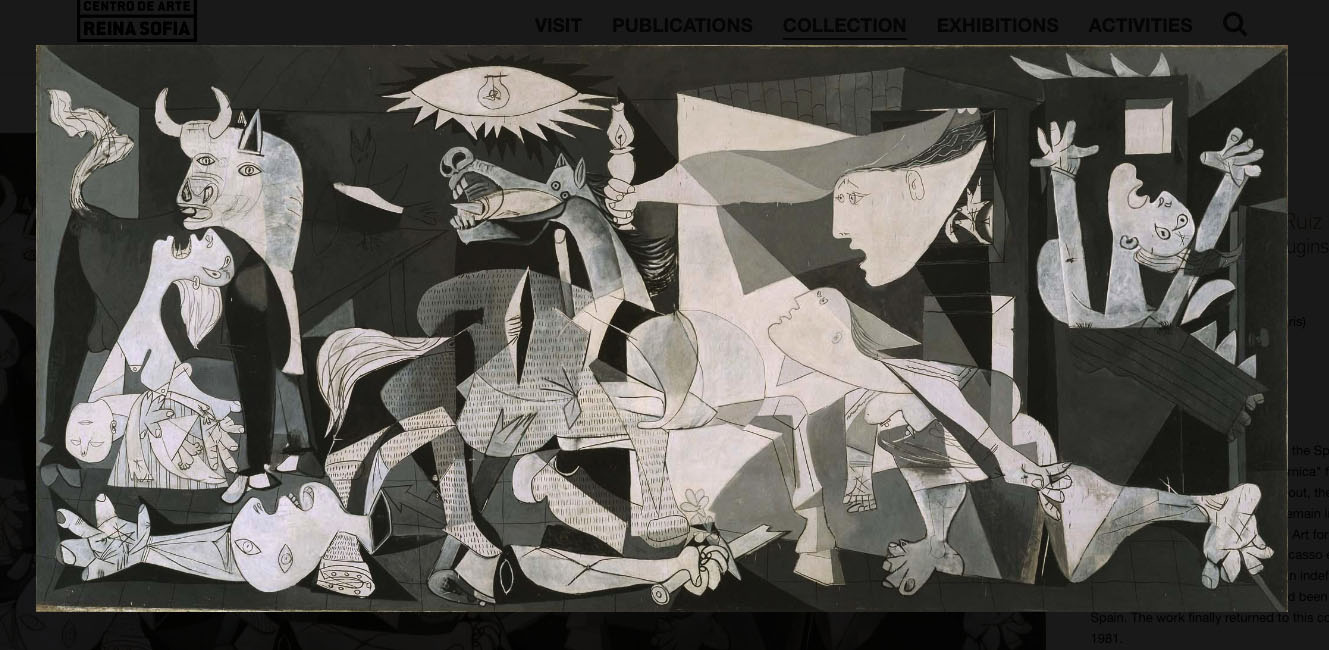

“Museums in Exile” opens with a room devoted to Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica” and the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. Many who have visited Madrid’s Prado Museum know that it houses one of the finest collections of art gathered from the 12th to the 20th centuries, but few are aware of the museum’s efforts in the thirties to prevent the collections from harm, when the Committee for the Artistic Patrimony (Junta del Tesoro Artístico) sought to save art from Franco’s bombing of the city.

No, painting isn’t made for decorating apartments. It’s an instrument of war against the enemy. —Pablo Picasso, Conversations with Christian Zervos, Cahiers d’art, 1935.

The trauma of the Prado Museum’s exiled collection is conveyed in this first room, along with the story of “Guernica.” Painted in 1937 as a tribute to Spaniards fighting the fascists, the painting could not be shown in Spain until after Franco’s death. You could say that the seeds of the “Museums in Exile” exhibition were sown in 1939, after progressive Spaniards and their allies lost the civil war with Franco’s fascists and Picasso organized, with Sydney Janis and the American Artists Congress, an American tour for “Guernica,” to benefit war refugees fleeing Spain. This was when a number of American painters first saw the painting, among them Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollack and Lee Krasner, who said, “Picasso at the time was one of my painting heroes.” After “Guernica” toured the US, Picasso entrusted this masterpiece to MoMA in New York, which in turn loaned it to a number of international exhibitions. (You’ll find “Guernica” today in Madrid’s Reina Sofia Museum, in the Sabatini Building.)

It happens that while MO.CO was putting this exhibition together, Russian troops invaded Ukraine and bombs rained down on cities, schools and cultural landmarks. As of June 23, 2022, UNESCO tallied 152 totally or partially damaged sites. The Arkhip Kuindzhi Museum in Mariupol along with its 2,000 works of art were destroyed. So was the Donetsk Regional Academic Drama Theatre, where hundreds were sheltering when the Soviet-era building was hit by two Russian 500 kilo bombs (Amnesty International deemed the attack a war crime).

Before you walk into the large space housing the Chile collection, you first enter a room filled with the work of 18 Ukrainian artists, where MO.CO informs viewers that ticket sales from the show will benefit in part the nonprofit Artists at Risk, which has hosted artists in more than 26 locations in 19 countries globally.

The pieces loaned by Chile’s Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende are mostly large and inspirational, and include work from over a dozen countries. I took the tour of the show with the museum’s director Claudia Zaldívar, who flew in from Santiago for its inauguration. When talking about “Museums in Exile,” Zaldívar said, “I can’t stop thinking about the fundamental role that art plays in human development, especially in times of conflict and affliction of communities. Art is fraternity, politics, reflection and community, four words that we see reflected in the history of the Salvador Allende Solidarity Museum.”

In 1972, Salvador Allende inaugurated the Museum of Solidarity. Following the 1973 coup in Santiago, Augusto Pinochet dismantled and pillaged the museum, which precipitated a mass exodus of the country’s artists. A number of these artists came together, as artist Ernest Pignon-Ernest points out in the “Museums in Exile” catalogue, “to create a collection to pay homage to Salvador Allende and to uphold his legacy, denouncing dictatorship and alerting the international community.”

Zaldívar pointed out that Allende had succeeded in creating a leftwing coalition, which in turn inspired French president François Mitterand’s socialist victory ten years later.

The collection of the Chile museum includes 1,700 works. Artists who donated while the Pinochet dictatorship was in full swing include Alexander Calder, Frank Stella, Roberto Matta, Wilfredo Lam and Joan Miró. Artists who donated to the Sarajevo collection include Mona Hatoum, Andres Serrano and Bill Viola. Among the many who contributed to the Palestine collection are Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Doisneau, May Murad and Fadi Yazigi.

In his introduction to the exhibition catalogue, MO.CO’s young director, Numa Hambursin, writes that, “To destroy the art of a country, of a nation, of a people is to take away their soul.” He argues that the theft, confiscation or destruction of art has occurred “in every war throughout centuries and continents, as have rape and slavery.” And he insists that we mustn’t delude ourselves into thinking that art is a luxury, something only for the well to do. No:

[P]eople need art as much as they need bread: one is as vital as the other. One must not think that this is a commonly accepted idea. When the ancient city of Palmyra was turned to dust by the Islamic State with bulldozers and dynamite, some commentators suggested that too much was being said about it rather than of the suffering of the population. When Notre-Dame de Paris burned down, some generous souls suggested that too much was being said about it and that the money dedicated to the restoration of the cathedral should instead go to the poor. When the National Museum of Brazil in Rio and the 20 million objects it housed went up in flames, I heard a journalist saying ‘Luckily, there are no casualties to mourn.’ On the other hand, politician Marina Silva described it as ‘a lobotomy of Brazilian memory.’

Out of the three “museums in exile,” however, only the one in Chile is presently open to the public; the Sarajevo museum, in a proposed design by Renzo Piano, is still pending construction, while the Palestinian National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art remains but a dream (see Where is the Palestinian National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art? by Nora Ounnas Leroy).

The four-year siege that desecrated previously multicultural Sarajevo cost the lives of over 13,000 people, along with the destruction of the city’s National Library and Olympics Museum. The association Ars Aevi then mobilized artists and museum directors and curators to propose exhibitions throughout Europe, and art was donated “to Sarajevo as a symbol of resistance to violence and of international solidarity,” as Pignon-Ernest notes.

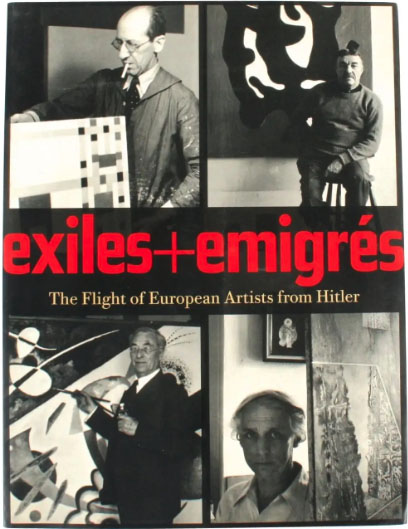

The three collections of art, objects and installations in “Museums in Exile” bear repeated viewing. The great emotion one feels when seeing these works and learning further about the troubles in Chile, Sarajevo and Palestine reminded me of a sister exhibition, “Exiles + Emigrés: The Flight of European Artists From Hitler,” that took place at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, from Feb. 23-May 11, 1997. LACMA curator Stephanie Barron and her team assembled more than 130 works in a variety of mediums, as well as architectural reconstructions and historical documents, including photographs, posters, books, pamphlets, letters, newspapers, and journals. It was a powerful testament on the political and social forces that drive large numbers of artists and intellectuals into exile, sometimes never to return.

Just as we say “never again” to genocide, the MO.CO exhibition instills in the museumgoer a sense of outrage at the horror of war and the injustice of exile. One wants to shout to the rooftops “Enough! Saner minds must prevail!”

Jordan Elgrably

Jordan Elgrably