Nora Ounnas Leroy

At the tail end of the MO.CO “Museums in Exile” exhibit (Chile, Sarajevo, Palestine), on view in Montpellier through Feb. 5, 2023, visitors find the last rooms of the collection that are reserved for the Palestinian National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art.

But let’s be clear: this museum does not exist, at least physically. For now, it is a project, a dream, a prayer, a challenge to time, to nations, to history…to silence. Far more, in my view, than the other two collections devoted to Chile and Sarajevo, this grouping of paintings and other works perfectly illustrates the concept of a “museum in exile,” putting one in mind of André Malraux’s axiom, “a museum is first of all an idea.”

The first batch of pieces supporting this collection were gathered in Beirut in 1978 by members of the PLO, but soon disappeared under the bombs, in 1982. In 2005, Gérard Voisin, UNESCO’s artist for peace, and Mounir Anastas, member of the Palestinian delegation, came up with the idea of a fund of works for Palestine, but this collection would remain available for viewing only to UNESCO members during internal conventions. The artist Ernest Pignon-Ernest, who had already led the “art against apartheid” campaign in the 1980s, launched the idea of a solidarity collection for Palestine in 2015, with Elias Sanbar, historian and writer, who was then Palestinian ambassador to UNESCO. A year later, a partnership agreement was signed with the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris to conserve, classify, list and enhance the works offered. Until now, the collection’s new acquisitions were exhibited once a year within the walls of the Institute only.

Elias Sanbar is now the director of the collection. “We are betting that life will always be stronger,” he says. “It is a museum of solidarity. The ambition is not to show Palestinian painters per se, but the work of world artists who are in solidarity, in a world that comes to Palestine since Palestine is imprisoned. We said, ‘whoever is in solidarity against the occupation gives a work,’ and it started like that…and since then, donations have been pouring in.”

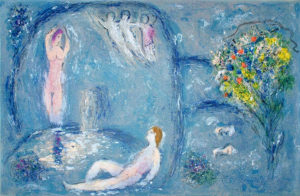

The collection includes many paintings and photographs, but also sculptures, comics, installations, and films (Jean-Luc Godard donated his last film a few months before his death). The works are chosen by the artists themselves. It is telling to observe what is donated to express support, because in this context, a work of art can no longer be defined by and for itself. It becomes almost automatically a sign, a message — a dialogue, with the Palestinian people, certainly — but above all it questions the viewer: And you, tell me, what are your thoughts, your feelings on the subject? How will you react?

There are works that reflect real-life situations (checkpoints, bombing, confinement, waiting), there are messages of hope, perspectives with openings, doors, windows, holes in the wall, girls jumping over the wall, vanishing point, stairs, a maze.

And then there are tributes to people. The figure who often comes up is Mahmoud Darwich, the great Palestinian poet, whose main translator was Elias Sanbar. Finally, many of the pieces reveal an inner point of view, a personal feeling, a state of being, or not being…and surreptitiously one feels the works are dialoguing with each other. Indeed, you can sense that these donated works are interconnected.

In an interview with TMR, Sanbar explained, “You have to know that in Palestine daily life is hell. Not only because of the repression, the annexation of land, the harassment…but because the basis of the occupation is to make your life unbearable, impossible, with the idea that at some point, you say ‘okay, you won, we’re leaving. The final goal is expulsion.”

Sanbar goes on,”The daily life of Palestinians is very, very hard. This museum must be a public museum, and the responsibility of the state is to put at the disposal of its people ‘beautiful’ works. It may sound a bit literary, but it’s fundamental. I think that beauty and aesthetics, beautiful things, are great levers of resistance.

“Apart from museums, you find an abundance of collections in Palestine, mainly private initiatives or those carried out by non-governmental associations. Archaeological and heritage collections that safeguard national identity are the first act of resistance against the occupier. A museum of modern and contemporary art is something else again. It is a question of questioning the present in order to look to the future, as most free and sovereign countries around the world do. Tel Aviv has its museum of ‘modern and contemporary art,’ a magnificent building with light and futuristic lines. The Palestinians do not have one. A simple observation.”

Sanbar also explains the importance of the present ‘museum’ collection for exiled Palestinians, visiting for the first time. “It is not only for the children, but also for their future prospects, to learn about the existence of a ‘national’ museum of modern and contemporary art in Palestine. This gives the illusion, even the imminent hope of the legitimacy of a State of Palestine, which unfortunately still has no legal recognition, need we remind you?” [Palestine was officially recognized as a State by a majority of UN member states on Nov. 29, 2012. ED]

Sanbar elaborates: “Although very recently, the Algiers Declaration foresees, by October 2023, elections for the presidency and for the Palestinian Legislative Council, which acts as a parliament for the Palestinians of the occupied West Bank, Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem. At present, Palestine is recognized as a ‘non-member observer state’ by 138 countries of the UN. And if we look closely, we realize that the French state, like the United States and many European countries, does not officially recognize independence and the State of Palestine.

“In 2013, the European, British and French parliaments voted their support for a recognition of the Palestinian state but without this being followed up by the governments to date.”

Commemorating the Nakba

However, an extraordinary thing has just happened, a real revolution, and you may be reading about it here for the first time: On November 30th, 2022, the United Nations passed a stunning resolution to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the Nakba, on May 15th, 2023. This is tantamount to declaring, for the Israeli and American delegations, that the creation of the State of Israel was a ‘humanitarian catastrophe,’ which they do not appreciate. The Permanent Observer of Palestine, on the other hand, welcomed the fact that the General Assembly had finally recognized the “historic injustice” that has befallen the Palestinian people.

In terms of solidarity with this Palestinian museum in exile, if we look summarily at the nationality of the artists who donated work, we notice that they are mainly of European and Arab origin, with a small but apparently significant share from Latin America. MO.CO director Numa Hambursin smiles at this suggestion. He believes that the Palestine collection is known mainly by word of mouth, and that many artists have actually never heard of it. If it is true that the collection was somewhat hidden until now, in its citadel on the banks of the Seine, let’s hope that the collection of the Palestinian National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art will quickly become known, now that it is starting to travel. It is clearly not utopian to imagine donations coming from the United States, Russia, Africa or Asia … and even Israel! (This publication has an international readership; feel free to share this article and spread the word.)

Beauty is part of the struggle. —Elias Sanbar

Since 2015, the collection has been slowly but surely growing, tucked away behind the photo-sensitive walls of the Institut du Monde Arabe. The MO.CO showing constitutes a great premiere, here in the south of France, with 44 works chosen by Numa Hambursin:

“Our goal,” he explains, “was to show the diversity of this collection in terms of media, artistic periods, and the nationality and age of the artists. But more than that, it is one of the rare exhibitions where big names of the art scene rub shoulders with lesser known artists on the same level. The issues of the collection go beyond the strictly artistic framework and allow us to transcend dogma. Here we abandon any idea of hierarchy between artists.”

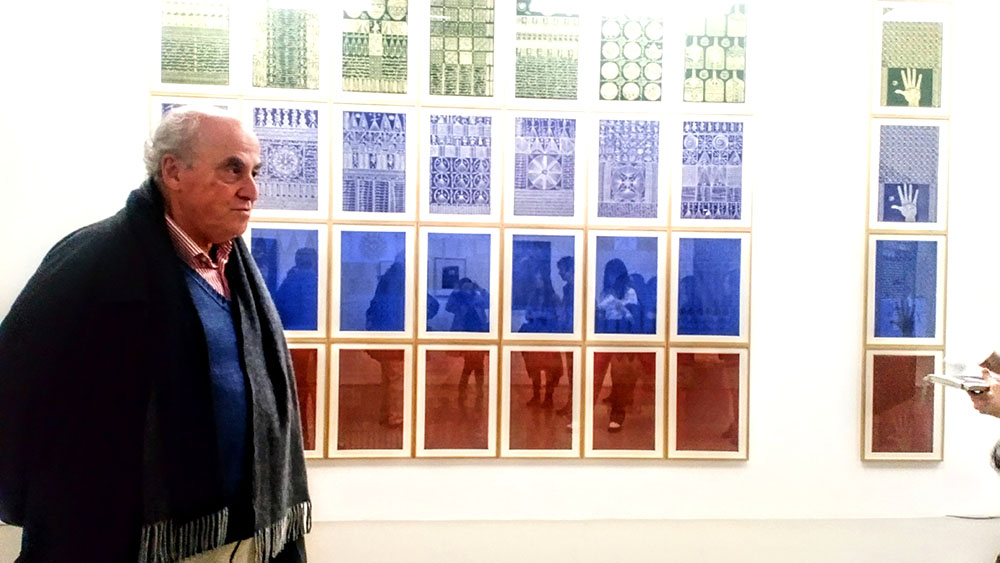

When you visit Museums in Exile, you notice that the part reserved for Palestine is not only underground and in the last rooms before the exit, but also upon arriving that you are faced with a wall. One can hardly ignore the significance of such a symbol — Wailing Wall, wall of shame, wall of annexation or division, wall of Apartheid, how many walls in Palestine, already? Here, MO.CO inaugurates a new kind of wall, that of the sacred and the spiritual with the work “The Invisible Masters” from Algerian artist Rachid Koraïchi. Decorated with 64 lithographs representing the teachings of great Sufi masters such as Jalal ad-Din Rûmi, Hafez of Shiraz or Ibn el-Arabi, the wall carries a message of hope and tolerance for future generations.

With respect to the installation of the works, Hambursin explains that the aim was to avoid any homogeneous path, in order to lead the visitor astray. Here, you enter a closed space, you arrive directly in front of a wall, and you have the choice of going left or right. And if you go around the wall, you come across the fresco “Exile Palestine” created in 2009 by Jacques Cadet, a pictorial representation of the real wall, the one built day after day in the West Bank. This contrasts with the other two collections, for Chile and Sarajevo, where one enters a space that is open but closed in on itself. There is a beginning and a natural way out, but both these museums are no longer in exile, even if the Sarajevo building hasn’t yet been built. Pinochet occupied Chile for “only” 17 years, and the siege of Sarajevo lasted “only” four years, while millions of Palestinians have been in exile since 1948.

“These two collections remain very homogeneous,” explains Hambursin. “The one in Chile reflects the strong politicization of art in the 1970s, while the Sarajevo collection carries the humanitarian dimension of the 1990s. The Israeli-Palestinian conflict has been going on for 75 years and we don’t know when it will end. We’re all a bit lost when faced with what’s going on over there. Here, we’re in a less collective adventure, the journey is more a matter of the personal involvement of each visitor.”

The journey proposed by “Museums in Exile” from beginning to end with these exceptional collections poses two fundamental questions:

· How to protect the art from war, from destruction and dehumanization?

· And how does art protect us in turn?

The viewer arrives at her or his own conclusions, but won’t be left unmoved by this monumental exhibition.

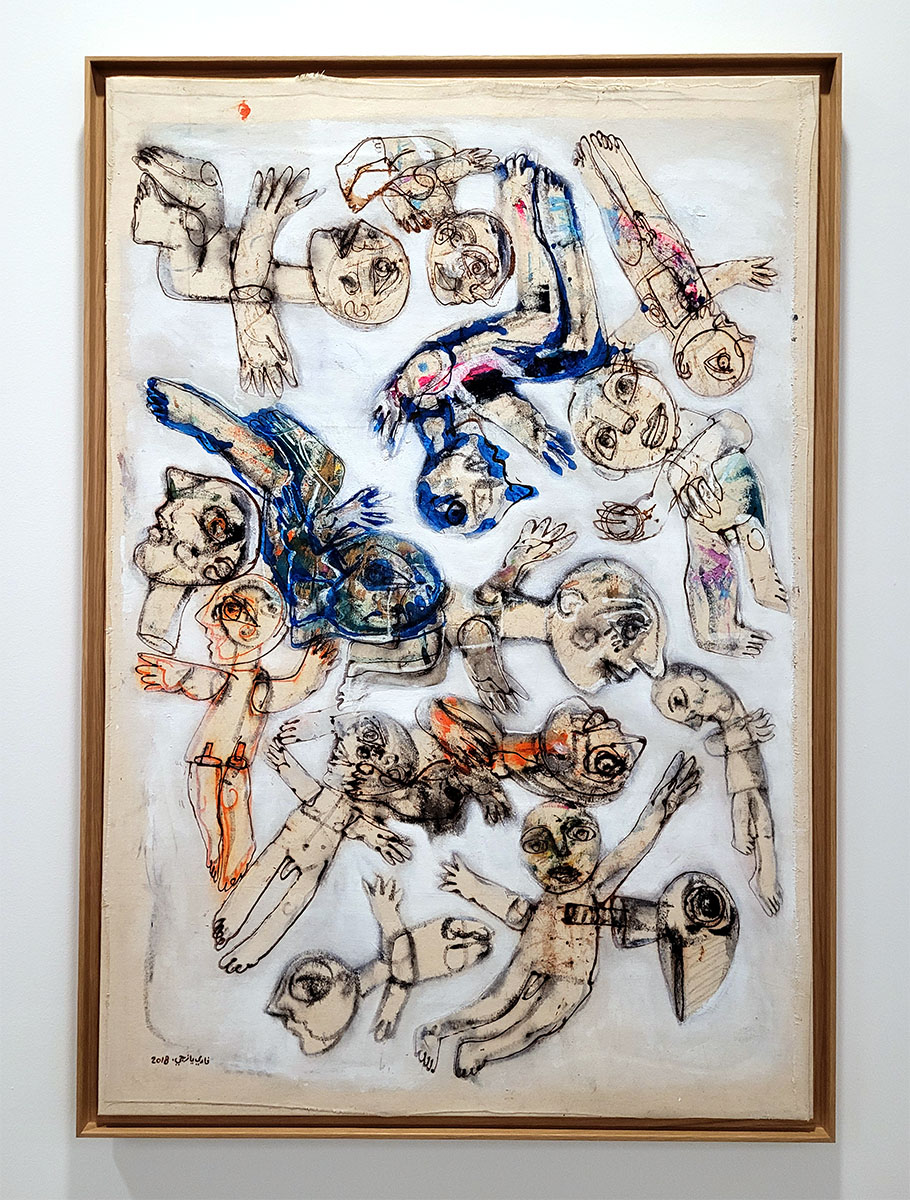

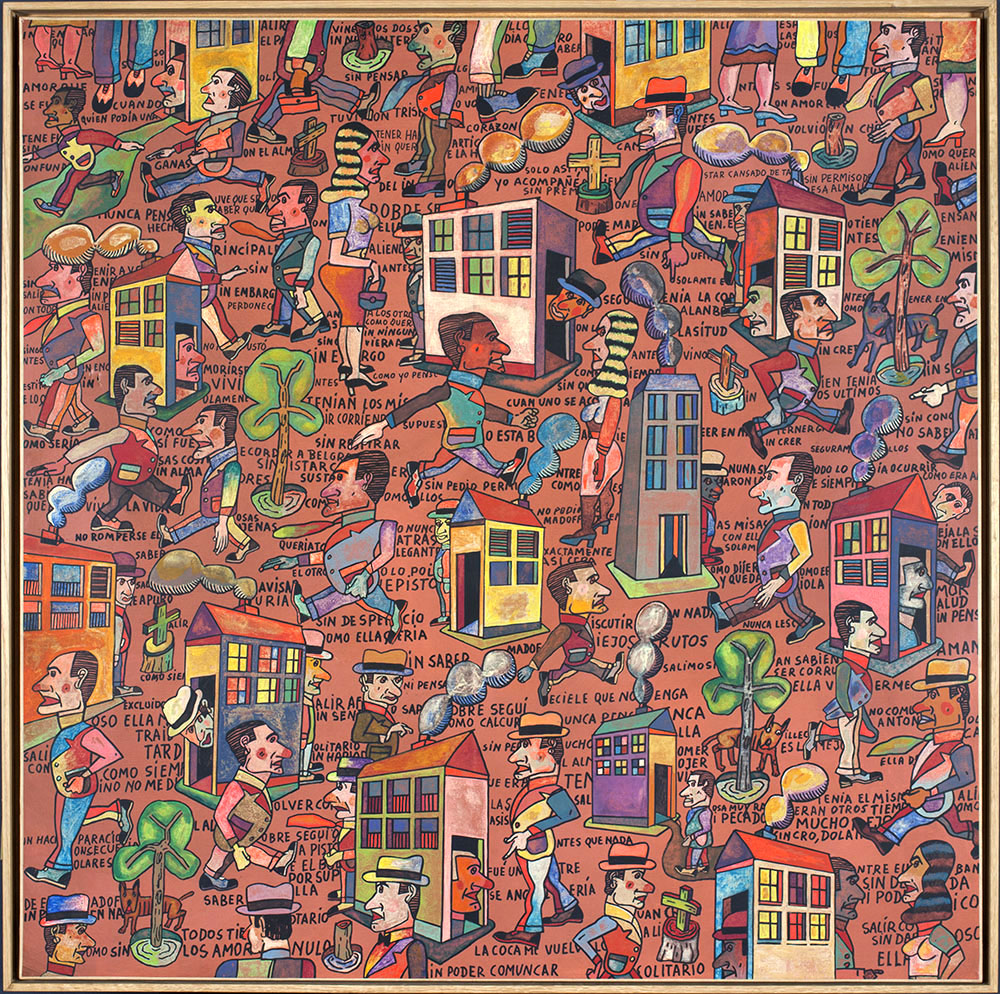

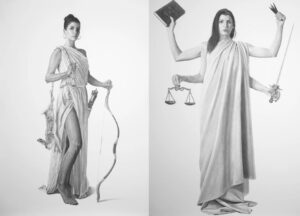

Artists present for the exhibition “Museums in Exile” as part of the Palestinian National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art:

Jean-Michel ALBEROLA (Algeria, 1953); Mehdi BAHMED (France, 1974); Taysir BATNAJI (Palestine, 1966); Pierre BURGALIO (France, 1939); Jacques CADET (France, 1941); Henri CARTIER-BRESSON (France, 1908-2004); Luc CHERY (France, 1962); John CHRISTOFOROU (Great Britain, 1921-France, 2014); Alexis CORDESSE (France, 1972); Henri CUECO (France, 1929-2017); Marinette CUECO (France, 1934); Gilles DELMAS (France, 1966); Armand DERIAZ (Switzerland, 1942); Robert DOISNEAU (France, 1912-1994) ; Joss DRAY (Morocco, 1953) ; Bruno FERT (France, 1971) ; Anne- Marie FILAIRE (France, 1961) ; Martine FRANCK (Belgium, 1938-France, 2012) ; Gérard FROMANGER (France, 1939- 2021) ; Anabell GUERRERO (Venezuela, 1955) ; Mohamed JOHA (Palestine, 1978), Valérie JOUVE (France, 1964) ; Mercedes KLAUSNER (Argentina, 1991) ; Rachid KORAICHI (Algeria, 1947) ; Julio LE PARC (Argentina, 1928) ; Patrick LOSTE (France, 1955) ; May MURAD (Palestine, 1984) ; Ernest PIGNON-ERNEST (France, 1942) ; Antonio SEGUÍ (Argentina, 1934 – 2022) ; Olivier THEBAUD (France, 1972) ; Robert TO (France, 1961) ; Marc TRIVIER (Belgium, 1960); Vladimir VELIČKOVIĆ (Yugoslavia, 1935-Croatia, 2019); Marko VELK (France, 1969); Gérard VOISIN (France, 1934); Fadi YAZIGI (Syria, 1966).

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)

Buena idea, un museo palestino.