Azoulay, heir to both French and Zionist imperialism, belongs as much to the ranks of the colonized as to those of the colonizers.

Sasha Moujaes

Translated from the French by Jordan Elgrably

Whether at Les Amarres for a screening of Ciné-Palestine, at Le Point éphémère for the Tsedek Ciné-Club, during literary encounters in Parisian bookshops, or soon in a storytelling and fabrication workshop at Petite Egypte, the year 2024 has been marked by the regular presence of writer, researcher, filmmaker and curator of anti-colonial archives Ariella Aïsha Azoulay in artistic and activist spaces in Paris. With the genocidal violence raging in Gaza, coupled with the muzzling of pro-Palestinian voices throughout France, Azoulay’s word is now inescapable.

Going against the grain of hegemonic identities manufactured by 19th-century imperialism, Ariella Aïsha Azoulay claims to be Jewish-Algerian and Jewish-Palestinian. Her father, a Jew from Oran who was naturalized French in colonial Algeria, moved to Israel in 1949. After his death, Azoulay discovered that he had kept her grandmother’s name, Aïsha, from her — a name she would later adopt. Although her family had lived in Palestine for three generations by the time Israel was proclaimed in 1948, her mother eventually embraced Zionist ideology. Azoulay, heir to both French and Zionist imperialism, belongs as much to the ranks of the colonized as to those of the colonizers. At the heart of the colonial universe articulated between Algeria, Palestine, France and Israel, Azoulay’s work places French imperialism in Algeria and Zionism in Palestine on the same colonial continuum.

Her reflections continue in her book, La Résistance des Bijoux. Contre les géographies coloniales (2023), which she dedicates to her “ancestors abandoned in the cemeteries of Oran and elsewhere in Algeria.” Azoulay’s first book to be translated into French (Azoulay writes in English), it was published in 2023 by Ròt-Bò-Krik[1].

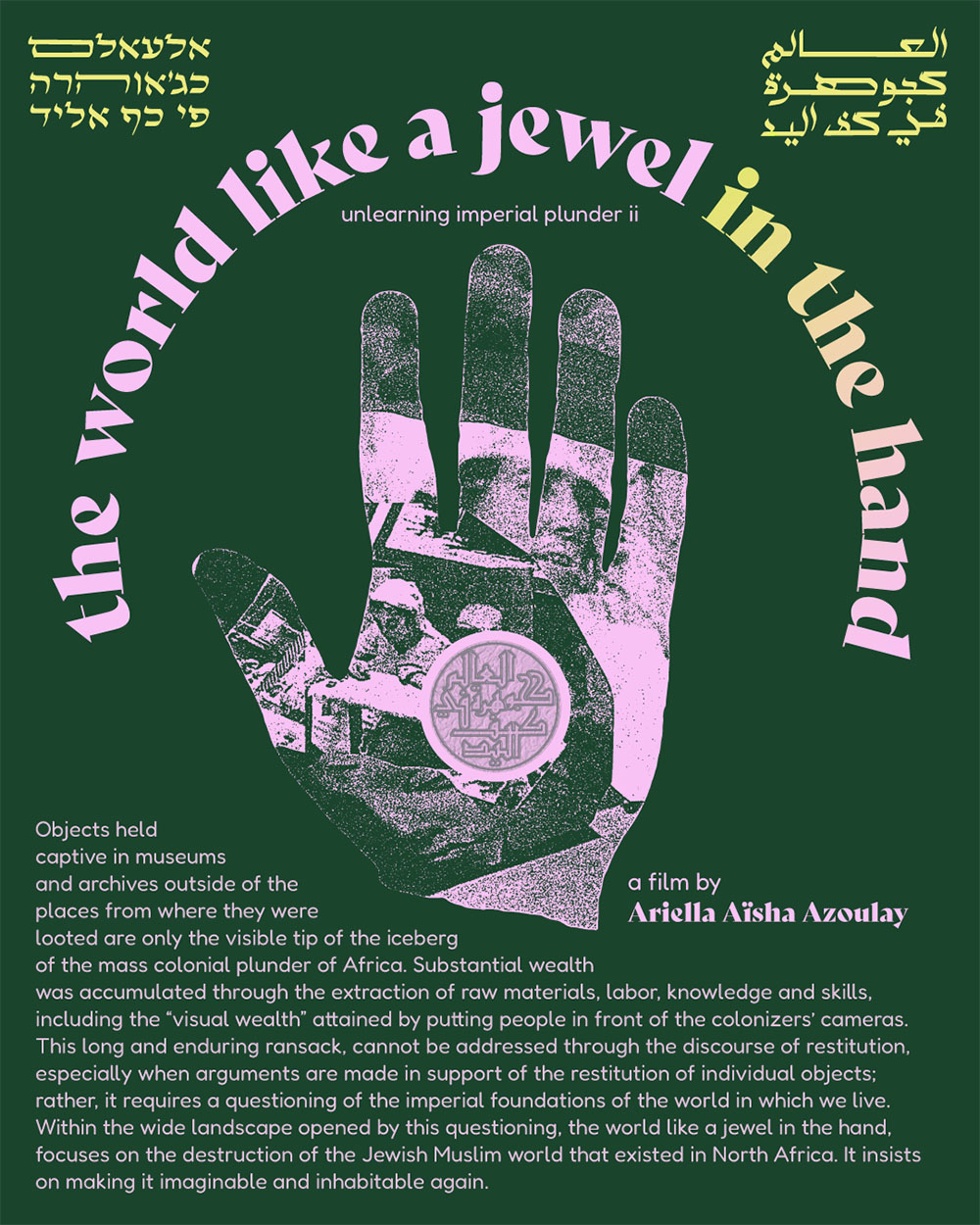

“The Language of the Ancestors,” the first part of the book, is a textual essay. It is the latest reworked version of the text “Unlearning Our Settler Colonial Tongues. On language and belonging” (2021), and translated to French by Jean-Baptiste Naudy. The second part is entitled “Les juifs sont encore là, dans chaque bracelet.” Built in dialogue with Azoulay’s documentary film Le monde comme un bijou dans le creux de la main (The World as a Jewel in the Palm of Your Hand)[2], this visual essay combines political theory, photography and poetry.

The Mizrahi identity, an invention of Zionism in the service of colonization in Palestine

The rationalization of colonial regimes in history was largely based on the creation of essential identity categories. These categories hierarchize entire populations, the better to subjugate them. With this in mind, the author examines the category of Mizrahim, a Hebrew word for the Oriental Jews [3] of Israel, which she claims was invented to legitimize Zionist colonization of Palestine.

Carrying the name “Azoulay” is no trivial matter in Israel. Young Ariella Aïsha Azoulay was aware of this from an early age. At Israeli schools, the epicenter of the Zionist ideological apparatus, she was constantly referred to as a Mizrahi, along with her classmates who also had names with strong Sephardic connotations. Indeed, the Zionist reading grid wants to make the Mizrahi the Israeli Other. The real Israeli, the early Zionist, is of European origin. He cannot be called Azoulay. The Mizrahi category, invented by “Euro-Zionist nomenclature,” has incorporated Jews from Arab-Muslim countries as an “inferiorized sub-group within a reformed Jewish people in the Zionist colony,” while positioning them as natural competitors to “Arabs”:

“[…] the production of the ‘Mizrahi’ category served to promote the qualification “Judeo-Christian” as an indisputable historical truth, implying de facto that every trace of the Arab or Muslim Jewish world had to be destroyed in the same way as Palestine had to be sacrificed.”

Nevertheless, her father, an Algerian Jew who became a naturalized Frenchman and then an Israeli, always firmly rejected his allegiance to the “Orient.” At home, the distinction is clear. Groups perceived as Mizrahim are not “us.” They were “the Other,” in particular Jews from North Africa who had not been granted French citizenship in colonial Algeria. But he wasn’t Oriental, he was French. For Azoulay, this assertion is as true as it is false. Born in colonial Algeria, the French authorities had condemned him to forget that he belonged to the land of his ancestors. He had never chosen to be French; the choice had been imposed on him. For Azoulay, there’s no question of questioning the emotional bond her father had with France, as this would be tantamount to reproducing the colonial view of who is “worthy” of being French, and who is not. To better grasp her father’s identity, the author refers to the notion of colonial amnesia, a mental state inherent in the journey of Algerian Jews, since France had elevated them to the rank of European civilization, while separating them from their world.

The fact remains, however, that the young Israeli woman was confronted at an early age with her father’s discourse, at odds with the reigning hegemonic thinking of his country. Her father’s distancing from Mizrahi identity was also nurtured by her sense of foreignness to the Israeli national myth, which he readily contradicts. Her father’s discourse appears as a subversive force, placing young Azoulay in a “new disposition to connect the dots and fill in the blanks.” Her father’s attitude towards the Mizrahi category, asserted at home, clashes, like a false note, with the process of assignment to this same category by the Israeli school. The dialectical relationship between chosen non-membership and subjugated assignment to the Mizrahi identity sets the stage for the author’s intellectual and political journey. Over the years, she has come to see the “similarities between the assignment of Israeli identity to the Jews of Palestine and the process by which French identity was imposed on the Jews of Algeria.”

Today, she defends the idea that Zionism has stripped the Arab-Muslim worlds of their Jewish components, since it antagonizes Jewishness and Arabness as two irreconcilable binary entities. By the same token, French colonial power also imposed this dichotomy, through the naturalization of Algerian Jewish groups[4], provoking a detachment from the social world that existed prior to the conquest of Algeria. Indeed, the Mizrahi identity “erased [its] belonging to the worlds that had existed for centuries and that had to be annihilated for Zionism to triumph in Palestine while destroying Palestine.” Despite the historical roots of Jewish communities in the vernacular of North Africa and the Middle East, nationalist expressions, both local and pan-Arab, eventually conformed to this nomenclature. They will then become accomplices in the annihilation of the Jewish existences of their histories, perceived as foreign bodies and completing the process already begun by Euro-Zionist colonial enterprises.

Unlearning Israeli Hebrew, dismantling the settlers’ language

Nor have Jewish lives in pre-Zionist Palestine been spared all the efforts of Zionist ideologues to erase them from their history. Even before the advent of Zionism, Azoulay’s maternal family resided in Palestine, at a time when anti-Semitic pogroms were in full swing in Europe. Expelled from Spain during the Inquisition, her ancestors had moved east from Ottoman territory, settling in the Balkans. Her great-grandparents eventually emigrated to Palestine, while the “Eastern Question” began to take hold among the European powers, combining covetousness for the declining territories of the Ottoman Empire with policies to influence ethnic and religious minorities. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire, followed by the division of its territories in the Middle East to the benefit of Franco-British imperialism, marked the beginning of the 20th century. Azoulay’s mother, whose presence in Palestine dated back three generations to the end of the British Mandate, eventually embraced the Jewish nationalist project in Palestine when Israel was proclaimed. Her obedience to Zionism and her desire to maintain her “image as a true sabra[5]”, became her “capital” in the Zionist colony in Palestine. Everything connected with life prior to the creation of the new Jewish state, in particular the roots of pre-Zionist Jewish communities in this once plural land, is no longer. The slightest contradiction with the Zionist national myth is doomed to disappear.

In this context, a “cohesive version of the Hebrew language” is imposed by the new Jewish nation. This language, emptied of its organic links with Arabic, Amazigh, Ladino, Yiddish or Turkish, renounced the “memory of all the choreography these magnificent Hebrew letters had once danced.” This is how Israeli Hebrew became the language of all Israelis, to the detriment of all other languages. Azoulay’s mother, like so many others, had to abandon her own mother tongue, Ladino, in favor of a language that was “foreign” to her and which she could only use “instrumentally.” This situation deprived her children of any contact with the language of their forebears. Yet it was only much later that the author came to understand that her mother “looked after this language as her personal reserve, hidden beneath what seemed to be a quintessential Israeli life.” Her mother’s much-vaunted sense of belonging to the Israeli nation was simply a way for her to “respond to an injunction” to “pledge allegiance to the national flag.” While she was still living in Israel, Azoualy was plagued by what she calls “language sickness,” to which she was for a long time unable to respond:

“It was only when I could conceive of the disappearance of Ladino that I understood that it wasn’t French that my father had deprived us of, but Arabic. Maybe not even Arabic, but Darija, and maybe not even Darija, but the Judeo-Darija my ancestors spoke. Or perhaps it was all these languages of my Algerian ancestors, which made up the language they spoke, without ever asking themselves […]: ‘Who are we?'”

Today, Azoulay no longer writes in Hebrew which she considers contaminated, simply to extricate herself from the violent processes underlying its evolution. One day, she hopes to use it again, this time reactivating Judeo-Arabic grammar to regenerate the language of her ancestors.

“The Jews are still there, in every bracelet”

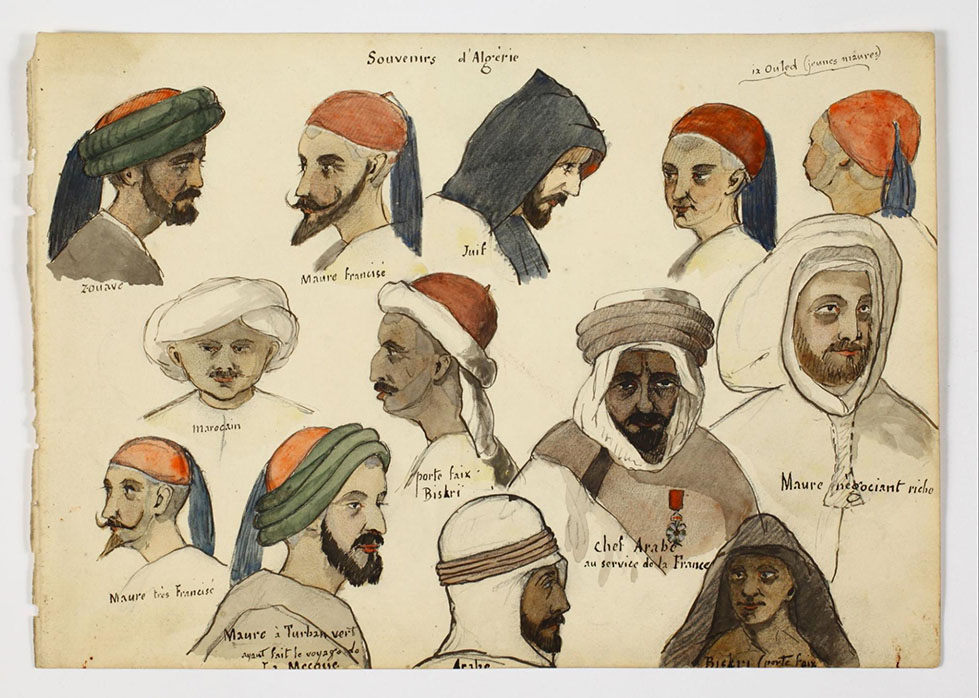

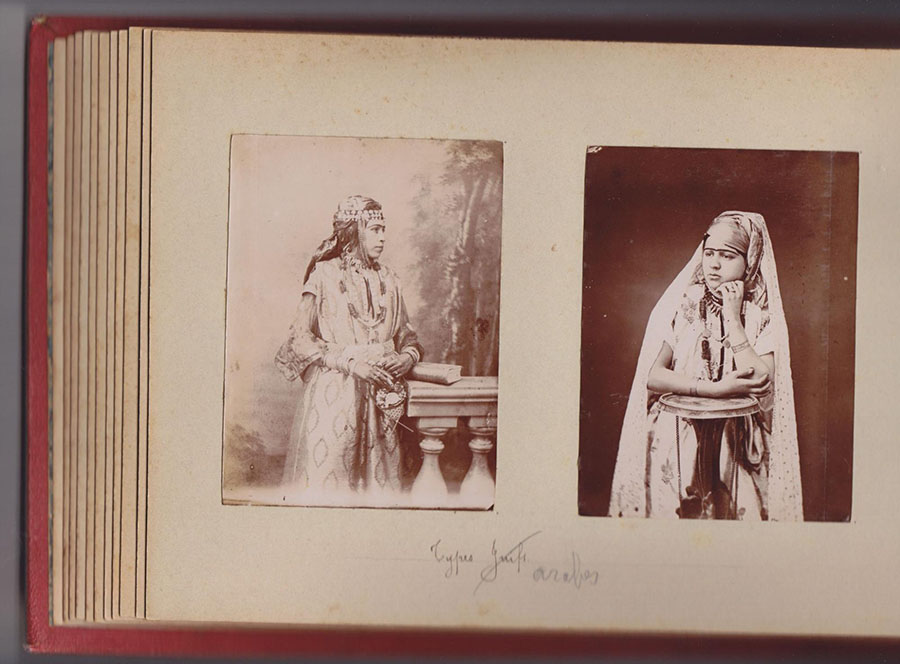

Since the death of her father, she has busied herself trying to piece together “the fragments of a world where the language of her ancestors expressed more than words and gestures.” But what can she do to find traces of her family, when she has no photographs in her personal archives? She immersed herself in colonial postcards, widely circulated during the era of European imperialism, and which can be found today in archives and flea markets in France. It’s true that the photographic medium is consubstantial with colonial domination. For to transform colonized populations into docile, governable subjects, colonial military power relied on a range of technologies, in the name of advancing scientific and artistic knowledge. In Azoulay’s approach, however, we find a strong gesture: that of appropriating the technologies of colonization, of subverting images specially designed to flatter the exoticizing arrogance of Europeans, of decolonizing the gaze. When she believes she recognizes herself in the images of all these Algerian women, whether “Jewish,” “Arab,” or “Berber,” Azoulay resists classification, exclusive and random, imposed by the colonial imaginary.

This “racializing obsession” with the “differentiation” of populations “into opposing groups,” inherent in Algeria or Palestine, as in all colonial contexts, resonates strongly with European imperialism’s fixation with the taxonomy of objects in colonial situations. Azoulay evokes “imperial caesuras,” which “occur and reproduce themselves” in the “objects that [European] museums collect, catalog and exhibit” to this day. Like the dislocation of Eastern Jews from their worlds by Euro-Zionist colonialism, or the purification of modern Hebrew at the expense of vernacular Hebrew languages, the colonizers “dissociated artifacts from the social world.”

Before their final departure in 1962, the Jews of Algeria were renowned for their craftsmanship in jewelry and goldsmithing. With the new classifications appearing in the inventories, jewels, once living witnesses to relations between Jews and Muslims, are reduced to mere individual designs, where “pure floating forms” are “detached from the bodies of their creators.” The destruction of these objects is also that of the craft infrastructure, in favor of the mechanization of these practices. The industrialization of jewelry manufacturing has naturally subjected its makers, particularly women and girls, to the exploitative logic inherent in the market economy:

“[…] the creation of jewelry, did not exist in the service of the market, but rather was part of social life. [This jewelry was now] forced into the colonial market, with its hierarchies, regulations and controls.”

The destruction wrought by colonial ventures is neither total nor irreversible. Today, despite looting and disappearance, the jewels and silverware made by Jews over the centuries continue to inhabit physical spaces, corporeal and mental of Algeria. But for Azoulay, the resistance of jewelry lies not only in the preservation of the artifacts themselves, or the restitution of those that abound in European museums. Resistance also involves rehabilitating the gestures of her forebears. Without really knowing it, her father, who had become a radio technician, had brought the practice of welding with him from Oran. Upon his death, Azoulay gathered together hundreds of loose pieces from all over the world, which her father had amassed over the years. One day, using a 1/16th mm drill, she began to pierce them, then thread them onto a waxed cotton cord. To undo these worlds destroyed by colonialism, she chooses to reactivate the muscular memory “infused with wandering pain and imposed prohibitions” of her ancestors, with a view to ‘reclaiming’ her membership of the ‘nation of jewelers.’”

As for us readers, we have no choice but to confront our own political, epistemological and intimate language, in an attempt, each in our own way, to “find a way out of the substitute worlds shaped by the colonizers.” For my part, originally from Lebanon, where the traces of French colonialism are still evident, I am forced to observe developments in my region from France. I am condemned to expose myself to the dehumanizing colonial imaginary that saturates the French political and media space. Above all, I can easily, and helplessly, place the Palestinian genocide in the direct wake of the colonial Euro-Zionist paradigms presented in the essay. If Azoulay’s writing resonates with such force today, it is because it lies in its ability to endow our era with a new system of meaning, inviting us to imagine something other than a world content to shatter Palestinian lives.

Notes

[1] Founded in Sète in 2021, this “small, independent, polyphonic, joyful and baroque” publishing house publishes books “that act as bridges between the utopias of yesterday and tomorrow”.

[2] Ce documentaire a été tourné dans l’espace de son exposition Errata, organisée à la Fondation Antoni Tàpies (Barcelone), du 10/2019 à 01/2020. https://fundaciotapies.org/en/exposicio/ariella-aisha-azoulay-errata/

[3] L’Orient se rattache davantage à un imaginaire colonial civilisationnel qu’à une aire géographique définie.

[4] The Crémieux decree, issued by the French government in Algeria in 1870, granted French citizenship to native Algerians of the Jewish faith. Muslim populations were excluded.

[5] The term “sabra,” first used to describe Jews born in Palestine before the creation of the State of Israel in 1948, now refers to anyone born in Israel.

Further reading

Azoulay, Ariella Aïsha, “Selection from Potential History” (Verso, 2019).

Azoulay, “Unlearning Our Settler Colonial Tongues: On Language and Belonging” (Boston Review 2021).

Azoulay, dir. Sans papiers: Désapprendre le pillage impérial, p202.

Azoulay, dir. Un monde comme un bijou dans le creux de la main (The World like a Jewel in the Hand. Un-learning Imperial Plunder II), 2022.

Azoulay & Negrouche, Samira. “CORRESPONDENCE,” (Rot. BO. Krik, 2022).

“Women have a voice #36: Inhabiting the Jewish-Muslim world according to Ariella Aïsha Azoulay” (Arteradio 2023).