I’ve read Yeats’ Second Coming a thousand times (things are always falling apart… the center is a luxury that others enjoy) and Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, where he insists that “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born; now is the time of monsters.” The now of 1929 Italy or of 2024 Gaza? If they’re all nows and everywhere there are monsters, when will tomorrow come?

Layla AlAmmar

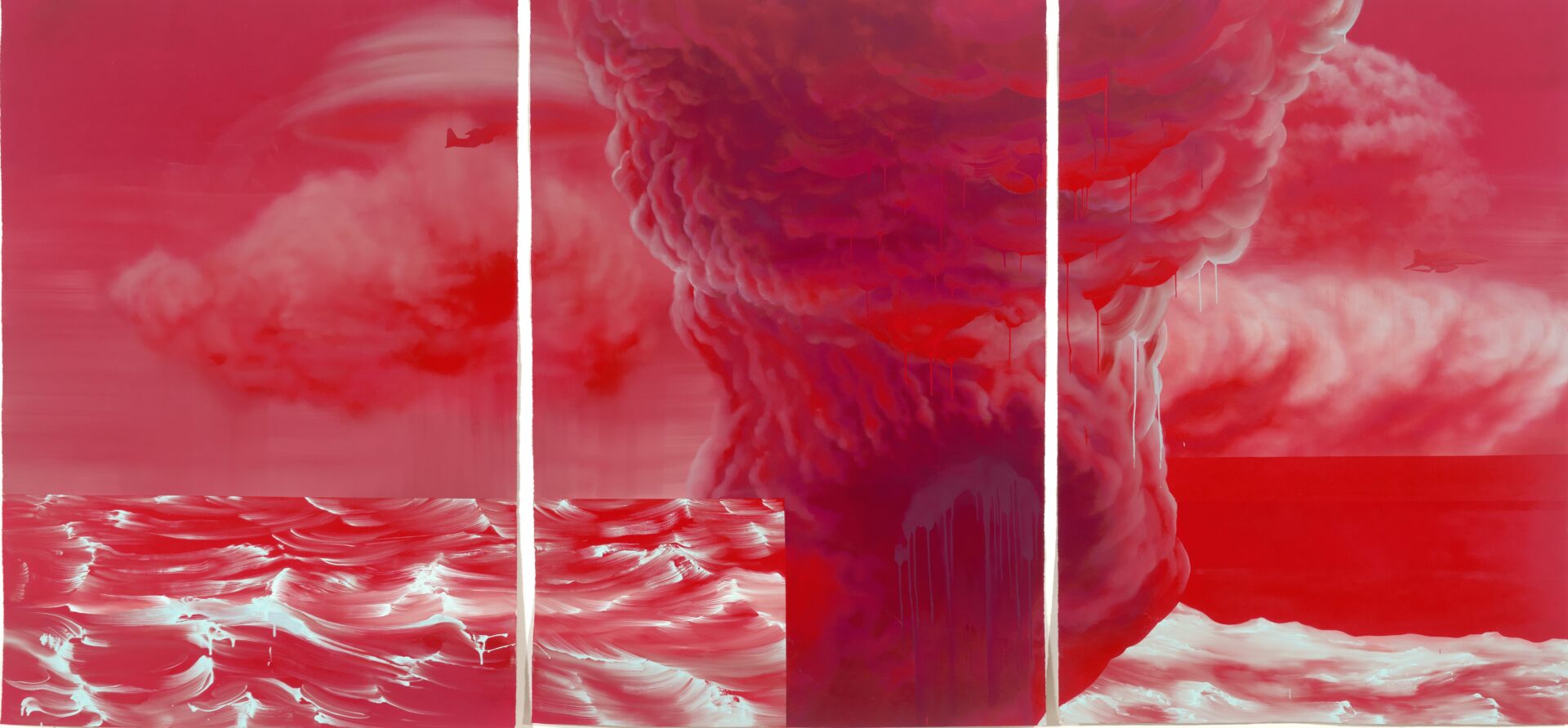

Of late, amid the carnage, the blood-dimmed tide, 128 days of unremitting terror as I write this, my mind slouches back in time. Like a raft in search of calmer shores, I drift, a hundred years into the past. The world was hardly quiet then, but when looked at from the “now,” history has a way of falling in line. Events will have been molded into some semblance of sense, to the extent that they seem almost inevitable at times. In the “now,” chaos reigns: breathing, thrashing, choking. In Khan Younis a mother carries her dead child away from a “safe zone” when, on Day 64, Bisan told us that memories were the only safe spaces left in Gaza. The chaos of the past, on the other hand, is static, locked, frozen by the icy indifference of Back then and Historically speaking and At that time.

Adrift in the 1920s, or thereabouts: I’ve been going over Gibran’s Mawakib with its line “pass me the flute and sing, for the flute’s song will outlast existence.” In the same poem, he advises us to be “ascetics in the face of what is to come and forgetful of what has passed.” As is usually the case, it’s more beautiful in Arabic. The word Gibran uses to describe what our disposition towards the future ought to be, zahid (زاهد), is one of those words that never quite comes over in English. It hardly accords with the rigidity and self-discipline that “ascetic,” with its cutting syllables, conveys. Zahid rather floats at the front of the mouth, a puff of air. It is to hover above earthly concerns because existence, after all, is fleeting.

Gibran was given to wading in such unfeeling waters. I wonder what he would have to say to Mosab, who can no longer feel his body because the explosions are happening in his heart.

I’ve been reading about Rashid Rida’s disillusionment with the Wilsonian moment and his turn away from what he called “the colonial deceit” of democracy and towards the fanaticism of the Wahhabis. Is that where it all went wrong? I’ve read Yeats’ Second Coming a thousand times (things are always falling apart… the center is a luxury that others enjoy) and Gramsci’s Prison Notebooks, where he insists that “The old world is dying, and the new world struggles to be born; now is the time of monsters.” The now of 1929 Italy or of 2024 Gaza? If they’re all nows and everywhere there are monsters, when will tomorrow come?

Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus is etched into the back of my mind, fixing me with his eyes, lidless as a fish. He has the head of a lion, the torso of a bird. He makes a mess of geometry. He’s much too worldly for so celestial a moniker. In 1921, nineteen years before he swallowed a handful of morphine pills, Walter Benjamin purchased the print (it lives in Jerusalem now) and re-dubbed him the Angel of History. In that off-center gaze, that open mouth, he saw a being powerless before the wreckage of the past. He saw the realization that nothing can be made whole again and the very fact that “things go on is the catastrophe.” On October 7th, a group of Palestinians tried to stop things, to stop the Nakba, to stop the catastrophe, from going on.

Resistance is both a right and an obligation.

The Al-Aqsa Flood broke through the northern wall surrounding Gaza. In the 14th century Ibn Battuta wrote that there were no walls around Gaza. But in the now, they call it an open-air prison. A misnomer of terrific proportion. Prison implies wrongdoing, a crime, a punishment that has been (one hopes) earned. A Gazan’s only crime is being born Palestinian. Gaza is a concentration camp, a killing cage, a barzakh between life and death. In his poem “Displaced,” Mosab writes, “I am neither in nor out. I am in between. I am not part of anything. I am a shadow of something.” In the now, Gazans are grinding animal feed to bake bread.

On Day 110, I listened as Dr Ghassan spoke of a three-year old boy whose limbs he’d amputated. A three-year old who was too young to know his name, and there were none left to remember it. WCNSF—an acronym birthed in Gaza. The doctor spoke of mounds of rubble smelling of decomposition, of strewn body parts, of quadcopter snipers and walking six hours to the south. He spoke of families who were tasked with deciding the order in which their loved ones would receive treatment. Should my father see the doctor before my brother? Is my cousin more critical than my sister? How do you rank love? He told us of a mother, tending to her son in an adjoining bed, whom he saw cradling the WCNSF in her lap the morning after surgery.

Resilience is resistance.

As the genocide proceeds, amid Freudian “ceasefire” slips and unintended Holocaust comparisons, Clinton whines about an Oscar snub and the papers of record twist themselves into passive, linguistic knots (Gazans are “found dead” and a toddler is referred to as “young lady”) to avoid saying what we all know to be true.

Israel is a state in psychosis. A rogue, terrorist entity. Zionism is, and always has been, a death cult. The demon spawn of imperial powers. A criminal, racist, fascist ideology that must, must, be dismantled. The masks have all fallen away. Tolerance, democracy, morality. Even the mask of denial has fallen. In the land of Bethlehem, the rough beast is thrashing…

In the throes of death? On Day 110, after Dr Ghassan gave his testimony, I watched Mustafa Barghouti speak of a global revolution, one which was returning the Palestinian cause to its rightful place as the foremost cause of our time. He spoke – with the sort of perennial optimism characteristic of politicians – of a mass movement able to compel western powers (those no less monstrous supporters of the Zionist entity) to waver in their long-held convictions. He spoke of the rise of the Global South, of cross-national solidarities, of Arab shortcomings and timidity. He assured us of victory, that a Palestinian state is in the offing. But as he spoke, all I could think of was the Angel with infinite tragedies at his feet, his outstretched wings straining against eternity. With each useless flutter, he says, “There’s no victory here, but I will remember you.” I saw Gramsci languishing in Mussolini’s prisons until his death. I thought about the failures of the Arab Spring, Alaa Abd El-Fattah, also languishing, in Egyptian prisons. Twenty-five years of war on Gaza, the murder of Shireen Abu Akleh, assaults on Al-Aqsa Mosque, raids on camps, and family homes demolished. Trauma that defies enumeration. My mind tumbled back to 1982 and 1967 and 1948 and the ruptures of the Nahda.

What I am saying is that we’ve been trying to burn this old world down for a hundred years, and nothing, absolutely nothing, began on October 7th.

Aboud’s smile is dimming. He tweets about Ramadan, hoping this will all be over by then. Netanyahu says he has months left in him and those displaced from the north are gone for good. Children drink from filthy puddles on the ground. The animal feed is running out and the people are eating grass. Day 126: Hind. All are born innocent but it turns out some are more innocent than others. In 1922 Eliot wrote, “I will show you fear in a handful of dust.” In Gaza, fear is redefined, or perhaps it’s just that language has broken down entirely and no longer serves its purposes. In 2024, Atef Abu Saif writes, “The list of my lost beloveds grows unbearably long.” The past is reduced to dust, smashed into shards, and nothing can be made whole again. Qahar (قهر) is another word that defies translation. A threshold emotion, tight with frustration. Enraged. Inconsolable. Mourning is also a luxury denied to us. Grief forever deferred. Journalists pray over the graves of loved ones then return to their microphones. In protests all over the world, Refaat’s kites fly high. If I die, you must live. Wael and Motaz side-by-side in a photo with a caption reading – ‘Our smiles are resilience.’

Resilience is resistance.

If the catastrophe is destined to go on, then so are we.