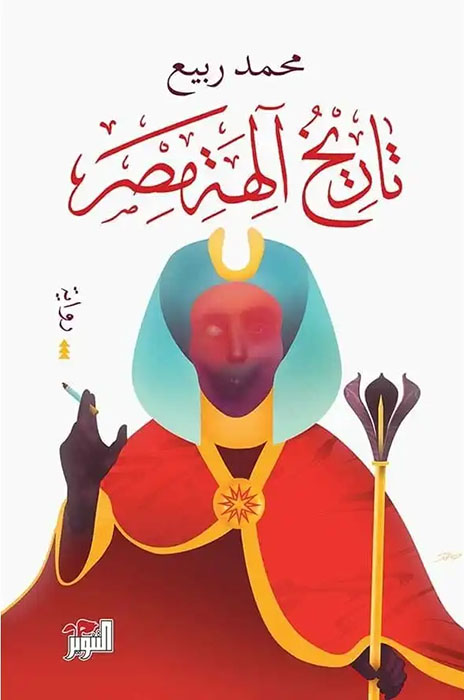

Renderings of the prophets and the grand holy tales of monotheism bring fire and brimstone into the life of a second-rate artist and his family, from Mohammad Rabie’s novel The History of the Gods of Egypt.

Mohammad Rabie

Translated from Arabic by Robin Moger

Noah, Ismail’s father, was a regular government employee, one of millions, who lived with his family in a little villa in Maadi which he had inherited from his father. Unfortunately, however, he believed himself to be an artist. A sculptor. He made little people, animals, buildings, things, which he called “minisecures,” and continued to make them apparently unaware that they were completely worthless. Little statuettes standing ten centimeters high: a peasant woman with a basket of vegetables, a peasant woman holding a pitcher, a police officer with a big moustache.

He grew reckless and made a little nude woman, arms at her side and her breasts on show. The deliberate sexiness of the woman made him smile to look at it. He could have sold his minisecures to tourists for a decent price; Noah the Sculptor could have made an adequate living as a craftsman, turning out hundreds of his minisecures for the market. But no: he’d decided that he was an artist. A single minisecure of this design, then one of another, and so on. He was a great artist, like Salvador Dali, not some horrible little man turning out horrible little figurines to be hawked in Khan Al Khalili.

When finally he gained entry to the home of Nagi Enani, the famous painter, he treated the latter with easy affection, as though they were colleagues, equals in talent and experience, and following a lengthy and wide-ranging discussion he divulged to Nagi that he had made hundreds of little statues. “Minisecures,” he said. And Nagi, who’d realized from the moment that they’d begun to discuss art that the man was hopeless, but whose good manners and modesty had prevented him from cutting their meeting short, now found Noah the Artist plucking up his courage and inviting Nagi round to see these minisecures for himself.

Noah possessed the naive optimism that comes with knowing you aren’t an actual artist while believing that deep down that you are a true artist: the conviction that all you need is a well-known friend to smooth your path to public recognition, to a gallery or an exhibition, to the attention of a critic, a celebrated artist. And when he sensed that Nagi Enani might slip free of him, he used all the cunning at his disposal and casually mentioned the famous story of the time a man had fallen to his knees before Nagi at one of his exhibitions and declared that he thought of him as a god, that he worshipped him. And just as Nagi, trembling, had backed away from that madman, so he now immediately gave up any thought of refusal and accepted Noah’s invitation. And no less immediately, Noah asked him to accompany him home that instant.

At home, Noah produced the minisecures from the old cupboard where he kept them, and lined them up on the table in front of Nagi, who, at seeing the first minisecure appear, realized what he had got himself into. So when the collection was finally assembled he didn’t wait to be asked, and launched into an encomium of the minisecures and the talents of the artist and sculptor who had created them.

Noah, though, wasn’t immediately persuaded. There was something off about the whole thing. He knew “The White Mechanic” was very poor indeed, straight trash, and that “The Goose Who Laid the Golden Egg” was a far better piece of work. As this was perfectly evident to him, an amateur, it should be equally clear to a professional artist like Nagi, but Nagi offered no criticisms of either the mechanic or the goose. Indeed, he didn’t criticize a single one of the many minisecures arrayed on the table before them.

A touch angrily, Noah said, “Fine. Are they lacking anything, though?”

“Nothing. I can’t see anything.”

“Nothing? Well what about their lines?”

“The lines are excellent. Exemplary.”

“The coloring?”

“Excellent. Keep painting them exactly as you have been.”

“The form?”

“The form?”

“Yes, the form. What about the form?”

“The form’s a success.”

“A success?”

“Well that’s the best thing you can say about form, that it’s a success …”

“A success!”

“A great success!”

“A great success?”

“That’s right. A great success.”

Noah was growing indignant, and when Nagi saw that the game was nearly up, he said, “But they’re lacking a theme. The minisecures, I mean. A framework with meaning …”

Noah almost fell to the floor from terror. This was huge. His minisecures … lacking a framework? With meaning?

“Eh?” he managed, tremulously. “Is that some new technique or something?”

“No no no. Nothing important. One can produce excellent art without giving it a framework.”

“But it’s better if you do?”

“Right.”

Nagi loaded his gun: “But naturally you’re not going to ask me how to do it.”

“Why aren’t I going to ask you?”

Nagi fired: “Because a true artist doesn’t need to ask the question.”

Noah spent months looking for a framework with meaning. He didn’t ask anyone for help, of course — Nagi’s bullet still lodged beneath his skin — but he did begin to reread the art books in his library, began to fly through them, scanning for the words “framework” and “meaning,” but failing to come up with anything that might count.

It was his TV habit that played the biggest part in creating what he was looking for.

Flicking between the three channels one Friday, his ear caught the name Lot, on the lips of Sheikh Al Shaarawi. Al Shaarawi was on screen, as he was every Friday following Friday prayers, explaining Quranic verses to his audience. As an artist and an atheist, Noah couldn’t care less about Al Shaarawi or Friday prayers or anything even vaguely related to religion. He regarded himself above these things. Such occultisms and myths weren’t worthy of rational consideration; better to turn his mind to his art, his minisecures. He didn’t despise these things, but he had no particular love for them, either. They just were. But the story of Lot, in particular, did hold his attention. Everything about it was deeply peculiar, from the city where men loved one another, to the prophet who chose to remain there for no clear reason.

As usual, Al Shaarawi was rehearsing the entire story from beginning to end. Nothing new there, of course: Noah had read it and heard it many times before. But as it was reaching its conclusion, as Lot and his wife were fleeing their village on the advice of the angels, Al Shaarawi said that, as the Torah told it, she (that is, Lot’s wife) was transformed into a pillar of salt, whereas in the Quran it says that Allah “destroys” her. And then, as was his habit, Al Shaarawi addressed his audience with a question, a rhetorical question: “Why is it, do you think, that Allah destroyed Lot’s wife?”

None of this had ever been of interest to Noah before, but now it was, because until this moment he had always assumed that the main thrust of the story ends with the destruction of Lot’s village, that this was the point and purpose of the story. He had never realized that the little tale tacked on the end had any significance at all.

Noah found himself ferociously focused on what Al Shaarawi was going to say next, and the sheikh had begun to answer his own question — “Allah destroyed her because…” — when the electricity cut out. And when it did, as the silence swelled in the sudden absence of Al Shaarawi’s mellifluous voice and the muffled clamor of the street came into the room, Noah decided that he had found the framework, the meaning, that he would affix to his minisecures. He would make little figures of the prophets, all of them, and set them in famous scenes from their stories in the Torah and Quran. Millions of images whirled round his head, paintings and sculptures of the prophets made during the Renaissance, and he resolved to revive this important piece of our shared human heritage — only this time, in the form of minisecures, none more than ten centimeters high. This was the framework, then, and he was clear about it. As for the meaning, well it would alter in accordance with the story.

In his head he began to plot out a minisecure for Lot. A great diorama depicting the prophet walking away from sinful Sodom, ablaze with glowing yellow flames reaching into the sky, and for his wife, a little neon bulb set vertically in the ground. A lovely modernist touch. The meaning of Lot’s story was as follows: the angels had warned Lot and his family not to look back, at the city aflame with Allah’s wrath, but despite the warning his wife turned and the sight of her city burning pained her, and she grieved, and felt that an injustice had befallen the city’s inhabitants. For this entirely human sentiment, Allah was angry with her, and punished her by turning her into a pillar of salt. A neon tube.

An hour later, as the electricity came on, Noah was still sitting in the living room at the back of the villa, eyes fixed on the television screen. Unconscious of the colors and sounds that came from the glowing box, he was planning away: more scenes from the holy books. He pictured all the prophets as carved figures on the big table in the living room where he sat, arranged in chronological order. He pictured the whole history of the Quran and Torah complete on the table, then he pictured himself, sweeping the room clean of clay and wood fragments and paint, painting its walls white, and then inviting his friends over — inviting all the artists of Egypt — to bear witness to his extraordinary talent.

Little Ismail was playing in the little garden outside the living room, just a few paces from his father. His mother, Dalila, came into the living room. She glanced once at the television, then at Noah, sunk in his dreams, and said, “What’s up with you?” And when Noah didn’t answer, she glanced out of the wide window overlooking the garden, at Ismail, and she opened the door and went outside and sat down in the cane chair that she liked. It was hot, she told Ismail, and he needed to drink a lot of water to make up for all the sweating he’d done, and then she entered into a long, cheerful, chuckling conversation with her son. She asked what he’d found in the garden. Any new discoveries? A new worm, he declared. He lifted a still-living worm, pincered in his fingers. Dalila thought to herself that this would be a perfect moment to explain the role of nitrogen in the natural world, then she hesitated. She thought to herself that being thirteen he wouldn’t understand everything she would say; maybe he’d understand a detail wrong, and so she decided to keep it as simple as she could, and she explained it to him like she was telling a bedtime story.

Ismail’s daytime world was bounded by school, the back garden, and homework. Evenings he usually spent with Noah in his studio, between the big comfortable armchair from which he would talk to his father, and the high wooden stool from which he’d watch what Noah was making on his worktable. When he grew tired of watching, he’d move outside, to play in the garden until bedtime.

Noah never made any effort to talk to his son about religion, but he did want Ismail to memorize the shorter surahs in the Quran for their beauty. He’d play recordings of the Quran reciter Sheikh Abdel Basit so Ismail could listen to the man’s beautiful voice. Noah also liked Sheikh Aboul Einein Sheisha. Sheisha’s voice, he thought, could be an opera singer’s voice: it had the rare ability to slide easily between tenor and counter-tenor. Ismail didn’t like Aboul Einein’s voice at all, it hurt his ears, but even so he loved to watch his father making his minisecures. Ismail liked to sit there, watching his father take a lump of clay in his hand, kneading it until it softened, then slowly shaping it, painting it, and then, when all the minisecures for one of his Quranic-Torahic dioramas were done, arranging each figure on a thin wooden board to shape the scene. And all this while, Noah would be telling his son the story of the scene he was making.

Noah noticed that his son was starting to respond to these tales — evincing astonishment, surprise, shock, incredulity on occasion — so he started to draw comparisons between the stories in the Torah and those in the Quran, explaining how the stories were forever contradicting one another here and agreeing there. The similarities between them made sense, of course, but explaining the differences required considerable effort.

Noah would work on his minisecures and tell tales as he worked, and Ismail would enjoy his father’s performances: absorbed in his task and talking away, then falling silent as he encountered a part that needed particular concentration, only to return to the dramatic variations of tone and pitch. And then the storytelling voice would fall still, his work on the minisecure would halt. He would ask Ismail to fetch him a new ball of clay, or a paint pot, or a thin knife, or a rag. And when an eager Ismail (helping his father!) had returned with what he’d asked for and settled back on his stool, his father would return to his task and his tales.

The day that his Arabic and Religious Studies teacher, Ustaz Ahmed, asked Ismail about his father’s job, the boy replied with a child’s pride, “Sculptor. Like, an artist…”

Anyone other than the gentle Ustaz Ahmed would have mocked the child, but he, always thinking positively, asked Ismail to explain to the class just what a sculptor does.

“He sculpts minisecures. He sculpts prophets. He sculpts Youssef as a handsome young man with Zulaikha running after him.”

Shock prevented Ustaz Ahmed from stopping the boy there. An enthusiastic Ismail ploughed on: “He sculpts Mohammed with Abu Bakr, hiding from the unbelievers in a dark cave.”

And now Ustaz Ahmed could remain silent no longer, but even then he managed to constrain himself. He didn’t get angry, didn’t bellow and roar. Simply, he thanked Ismail, then turned to a classmate and asked him what his father did.

The next day, in Religious Studies, Ustaz Ahmed said that those who sculpt statues shall enter the fire with the unbelievers. And he said that those who sculpt statues of the prophets shall enter the fire and shall never, ever, leave it. “Haram,” he said, “Haram haram haram,” and then, as was his wont, went on to describe the torments of the grave and the torments of the fire and for the tenth time, describe in detail the skin of the tormented burning in the fire, only to be replaced with new skin and burned again. All of this was mentioned in the Holy Quran, he said. Modern science had proven that people only feel pain in their skin, he said. He said that this was confirmation of the Miracle of Science in the Holy Quran.

That afternoon, Ismail went home frightened and sad. The fire, consuming his father’s skin, then Allah giving him new skin to be burned again. Apparently endlessly. This business of the fire was very upsetting. He didn’t want to burn down there in the darkness and the heat, with the scalding water and the blackened flesh and the roaring flame, the gas bottles and ovens and grills. He didn’t want to see his father burning without being able to help him. No. He wanted to remain by his parents’ side in the beautiful place they called Paradise. The only solution was to ask his father to stop making the minisecures.

By this point, Noah had finished all his Quranic-Torahic minisecures and had laid them out in order on the living room table, from Adam to Mohammed. Beginning to End. It all looked absolutely beautiful — Noah’s little world — and more beautiful still, it preserved both the framework, and the meaning, too.

For instance, because he was particularly interested in Jewish history, and because he found the story of wandering lost in Sinai for forty years particularly fascinating, Noah had made minisecures of a huge number of Jews: hundreds of little Jews each ten centimeters high, all sprawled out in a shady valley in the middle of the desert. He placed them sprawled out around the plate of blue acrylic that represented a spring, or sprawled beneath the scattering of little wooden palm trees, or inside the many little tents erected round the spring, and on a little tin-tag signpost which he erected by one of these tents, he wrote: The Byzantine Wandering. He wanted to make it clear that the Jews weren’t lost at all. They were only lazy. When he’d finished the diorama, he started to inspect it, asking himself whether he’d got the meaning across or not, and decided he would leave it as it was. The ambiguity, perhaps, served the piece’s artistic aims.

Then, how had Noah (the prophet, not the sculptor) managed to transport all those creatures in his ship? Noah the sculptor fashioned a little planet earth, about twenty centimeters in diameter, over which, and almost touching it, and balanced on a few little staves, sat a huge ship, almost the size of the globe itself — about 20 centimeters high and from 30 or so from stern to prow. The globe was covered in acrylic paint, blue all over, while the ship looked big enough to accommodate all earth’s creatures in its hold. Anyone looking at the piece would surely ask themselves what size planks you’d need to build a ship that size, whether the planet was capable of producing that much wood in the first place, or the fabric required to make the sails, whether there’d be any need for sails in circumstances, if the ship could balance on the globe at all, if the artist’s mind itself wasn’t unbalanced … On the blue globe, Noah had written: There’s a place for bacteria, too.

His favorite was “Jesus: Three Studies in Physics.” Three identical crosses, the same group of figures around each: some women, more men, and Japanese soldiers wearing World War II-era uniforms. The three groups were identical in size, coloring, and disposition, but on the first cross Noah had fixed a little minisecure of a white-skinned man with a neatly combed brown beard and wide, incredibly deep-set eyes. The man was crucified, facing forward, his slender, well-muscled body positioned on the cross with extraordinary elegance. The second cross held the minisecure of a man with a mutilated face turned to one side. He looked unconscious. His body was completely naked and filthy, covered in cuts and blood, and his skull was caved in. He had a tiny, sad little penis. There was nothing on the third cross.

Ismail liked to go and look at the minisecures on the big table and admire his father’s skill. He liked to lever open his father’s big art books and page through the works of the great artists, chronologically arranged. The different paintings and statues of Christ: a man fixed on two beams of wood in a manner that seemed magical, incomprehensible, sometimes sad and sometimes wearing a faint smile, though most frequently his expression was completely neutral. And when Ismail had finished looking at the pictures in a book, the pictures of Christ and the rest, his eyes would slide to “Jesus: Three Studies in Physics,” and he would understand that there was no difference between what all these artists had made and what his father was doing. And his sadness would deepen to think that all these artists had the perfect right to paint and sculpt Christ and the rest of the prophets, but his father was going to go to hell for doing the same thing.

With time, Ismail grew preoccupied with what he had started to learn and discover about the little world around him, and gradually, the dilemma of his father and the hellfire began to fade.

One day, some two years after his father had completed his minisecure of Quranic-Torahic history, Ismail was sitting on the ground and watching the little snails in the villa’s garden, rediscovering them for the hundredth time: their slow progress over the soil, the leaves of the plants. Ismail had begun to show an interest in the Torah, the Quran, and the Gospels. He read large chunks of all three and, as was to be expected, had understood nothing. More irritating still — to Ismail — was that the Torah and Gospels were combined into a single volume called The Sacred Book while the Quran was a separate volume, The Holy Quran. Since Allah was the source of all three, the distinction was surely meaningless. Also irritating was the fact that the number of lines per page in The Sacred Book and their font were radically different from the line-count and font of the Quran. Every day he told himself how much better it would be if someone were to publish the three books in a single volume, arranged in the order they were written and released: the Torah then the Gospels then the Quran. And it was on this day, now so long ago, that he decided to return to his father’s studio, remove a large quantity of paper from the drawers and, with the aid of staples and glue, construct himself a single vast tome, into which he would transcribe, in a neat hand, all three together.

He gave a lot of thought to what he would call this book. The Torah and the Gospels were known as The Sacred Book, he told himself, and the Quran was The Holy Quran, and so (and since, too, he loved the Quran, because its Arabic was beautiful and actually comprehensible) he decided to entitle this collected works: The Sacred Torah and The Beautiful Gospels and The Very Very Holy Quran. His secret hope: that his project would find favor with Allah, Who would forgive his father and admit him into heaven.

He had just abandoned the snails and brushed the dirt from his hands, when he heard his father entering the living room.

Ismail stood still. He could hear his father shouting unintelligibly, in a fury. At first he thought there must be someone else in there with him, but listening, and failing to hear any answer to his father’s cries, he realized that he must be addressing himself. Crouching slightly, he moved slowly and silently over to the window, then inch by inch he carefully raised his head to see in. He could hear a loud, continuous thumping.

By the time Ismail got his first glimpse inside, his father had smashed everything up to the prophet Noah. He saw him pause for a moment, then lift the broom over his head and bring it down on the table. He was screaming with rage and trembling violently. He continued to destroy everything on the table, then swept the pieces onto the floor and stamped on them until they were well and truly pulverized. Swearing and screaming. Screaming at the minisecures. Blaming them. Nothing he said made sense to the boy, nor did his anger.

Carefully, Ismail drew his head back down, and then trotted in a crouch to the far end of the garden, coming to a halt behind the trunk of a little tree. It made him very sad that the minisecures were all smashed up and that his father was angry, that he was shouting and talking to himself and furious with things that couldn’t speak and didn’t move and had no mind of their own. Things that he himself had created and that did neither him, nor anyone else, any harm at all.

Minutes passed. He saw fire flicking upwards inside the living room. The flames glowed brighter and brighter, the window shattered, then his father came out of the door carrying a big red fire extinguisher. He set the extinguisher on the ground beside him and stood staring through the window frame into the living room. As he slowly smoked a cigarette, the fire illuminated his face and his clothes. When the cigarette was finished he flicked it into the fire, then picked up the extinguisher by its handle, pointed it at the flames, and sprayed white foam through the window. The fire went out in seconds.

The smell of the smoke was strong. Despite his sadness at everything that had happened, and despite the fact that his father was now sitting in the cane chair and once more muttering unintelligibly to himself, more softly and slowly than before, Ismail felt a calmness grow inside him. A certainty that everything was all right. His father had smashed all the minisecures and now he wouldn’t enter the hellfire when he died; he would enter Paradise, with him.

Author’s Note

I was in the first year of middle school, six years of primary school behind me. At the time, it felt like the new school year was the first step down a rockier road: lessons would be harder, I told myself, and good grades would take twice the work. It’s clear to me now that the rocky road didn’t run through the new curriculum, but rather the series of dazzling discoveries that continue to reveal themselves to this day.

I was in a classroom, in Saudi Arabia. The Arabic teacher I adored was unpacking a verse from the Quran and telling the story of Moses and Pharaoh, something I knew very little about. I can’t remember what lesson it was, but I assume it was something like Quranic Studies.

The teacher was giving his exposition in that way of his, soliciting your engagement, encouraging you to try and respond to his quick, clipped questions, asking the boys to raise their arms if they wanted to answer and giving the go-ahead to those he trusted would get it right, so as not to break the rapid flow of his tale.

He came to the verse that mentioned “the unjust people,” a reference which, I’d come to learn, would recur frequently in the story of Moses. “Who are the unjust people in this verse?” he asked. In my eagerness I answered without waiting for permission — “The Jews!” — and perhaps my error amused the teacher, because he said with finality, “Wrong. The unjust here are the Egyptians.”

The emotion that swept over me in that instant was a complicated one. I realized that I had been far too hasty and that my answer had been beyond stupid. How could the Jews be the unjust ones in the story of Moses, after all? But the real shock was that the Egyptians were the bad guys, and the Jews were good.

A few days later, idly looking through my father’s library, I discovered that the same story, with a few minor variations, was related in great detail in the Old Testament, the holy book of the Jews, which made a lot more sense than its appearance in the Quran. I already knew that Muslims were enemies of the Jews, and my discovery prompted me to ask what the purpose was of reprising the story in our book; why hadn’t Allah just incorporated the Old Testament into the Quran instead of retelling its stories? Why didn’t we have a single volume of revelations that held them all: The New, The Old, and The Oldest?

A few months after that, I would hear the name Minerva spoken on TV, on some religious program, and would immediately ask my father about it — I didn’t have the patience to go through his books this time. He pointed me to the delights of Drini Khashaba’s Myths of Love and Beauty in Ancient Greece in which I discovered (with difficulty, given the difficulty of the author’s style) that Minerva was a goddess, that there were many gods in the ancient world; that these gods fought among themselves and gave birth to yet more gods. Chaos when compared to Islam, the straightforward monotheism of a young boy making his way into adolescence.

Without much prompting from my father, from anyone else for that matter, over the course of the years I slowly but surely came to understand what every one of us learns: that the tale is told from the teller’s point of view, that there’s always a second party of whom we know nothing, and that the other world is more attractive than our world, only because we already know ours so well. After all those years, at last, I discovered that nothing is certain.

And in the years that followed those years, I came to see that childhood trauma leads us down certain paths as adults, most often tragic paths; that one way or another the majority of the people I know had suffered as children; that maybe no one’s childhood had been free from trauma and tragedy even when it looked from the outside like they’d led an easy life. But those children who were raised in the shadow of some crazed dictator (and there’s plenty of them these days), or who lived through endless war, or with a father (or mother) with mental illness — I never took them into account, because I was completely unable to picture their futures.

The above passages are taken from my novel, The History of the Gods of Egypt (Beirut: Dar Al Tanweer, 2020). One of the themes of this novel is the mental illness caused by living in a dictatorship, and how this illness can be passed down in a family from parent to child without either party being conscious of the process. These passages were written with a single purpose in mind: how can we spare our children from our own afflictions?