You may not have heard of her until now, but as South African Nobel Laureate J.M. Coetzee marveled of Adania Shibli’s third novel, she “takes a gamble in entrusting our access to the key event in her novel—the rape and murder of a young Bedouin woman—to two profoundly self-absorbed narrators, an Israeli psychopath and a Palestinian amateur sleuth high on the autism scale, but her method of indirection justifies itself fully as the book reaches its heart-stopping conclusion.” Finalist for the National Book Award, Adania Shibli is one of Arab literature’s prodigious younger talents, and Minor Detail, which was 12 years in the making, is the work she was destined to write. Reviewed by novelist Layla AlAmmar.

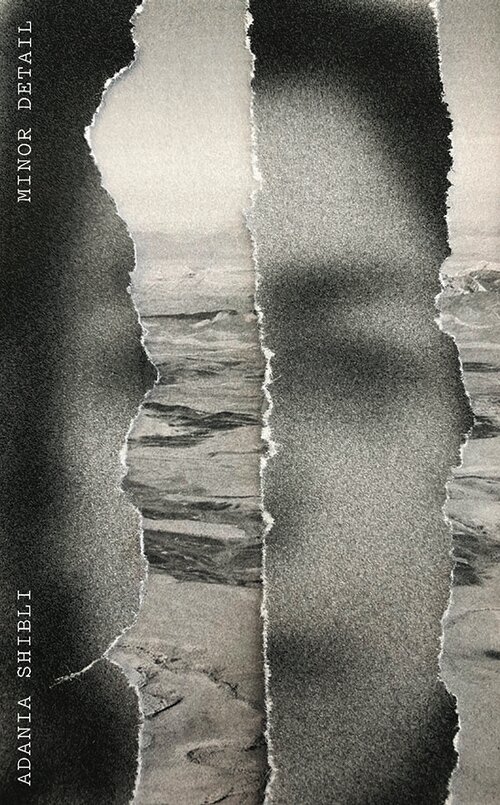

Minor Detail, a novel by Adania Shibli

Translated by Elizabeth Jacquette

New Directions 2020

ISBN 9780811229074

Layla AlAmmar

In light of the infinite array of atrocities, actual and symbolic, perpetrated on the Palestinian people over the better part of a century — forced displacement, occupation, human rights’ abuses, ethnic cleansing, bombings and besiegement — the murder of a lone Arab Bedouin girl in August 1949 hardly warrants attention. However, the chilling fullness of this small event forms the backbone of Palestinian author Adania Shibli’s latest novel, Minor Detail (trans. Elisabeth Jaquette). The first half of the narrative fictionalizes this incident. Told from the perspective of an Israeli commander, it takes place over four days in (what became) the Negev desert when a group of soldiers—tasked with “cleans[ing] it of any remaining Arabs”—massacres a tribe, takes one of its daughters captive, gang rapes and kills her. The novel mirrors the reality of what followed, whereby the crime was covered up by authorities, only coming to light fifty years later. Consequently, the second half of the narrative takes place in the early 2000s when an unnamed Palestinian woman in Ramallah becomes obsessed with the incident after reading about it in the newspaper one day.

Even she is perplexed as to why she should be so consumed by a small historic tragedy when the present is “no less horrific.” She initially chalks it up to the fact that the crime occurred twenty-five years to the day before she was born, i.e. 1974, which incidentally is the author’s birth year. The second section becomes a journey to discover what the narrator calls “the complete truth which, by leaving out the girl’s story, the article does not reveal.” Uncovering the girl’s story, giving her a voice, is Shibli’s (equally futile) task in the metacontext of writing the first half of the novel.

So often these types of stories—which deal with the legacies of collective historic trauma, such as, in this case, the 1948 Nakba—aim to give voice to the voiceless and recover buried ordeals in a kind of redemptive, quasi-triumphalist gesture. Recover yesterday in service of a brighter tomorrow… or some such claptrap. However, as we’ve come to know from her two previous novels, Touch (trans. Paula Haydar, 2010) and We Are All Equally Far From Love (trans. Paul Starkey, 2012), Shibli is no ordinary writer. Her fiction is experimental and complex, frequently upending the conventions of the genre: characters are unnamed and lack personal histories; the structures of the novels are porous and fragmented, composed of vignettes and isolated chapters that you have to reach through and across in order to make sense of the whole; and there’s a lack of overt revolutionary zeal or nostalgic harkening to a pre-1948 existence. Shibli’s prose is precise and tactile, creating a holistic atmosphere of overwhelming anxiety that afflicts her characters, as in the second part of Minor Detail, where the protagonist notes:

I rush to close all the windows until I get to the big window, through which I see how mercilessly the wind is pulling at the grasses and trees, shaking their branches in every direction, while the leaves tremble and writhe back and forth, nearly ripping off as the wind viciously toys with them. And the plants simply don’t resist. They just surrender to the fact of their fragility, that the wind can do what it wishes with them, fooling around with their leaves, passing between their branches, penetrating their boughs…

What is laudable about the translations is how they make no effort to bring the texts closer to an English-speaking audience. They stay true to Shibli’s intention of confronting, head on, the limits of empathy. Her novels keep the reader on the outside, in a state of profound and jarring unsettlement, which mirrors the suspended alienation that is (and has been) the condition of Palestinians everywhere—erased, suppressed, estranged.

The fundamental, inescapable impossibility of reclaiming the Bedouin girl’s voice stands front and center in this story. The fastidious commander of the first section neither cares who she is nor understands her language. And so, all we hear is her “babbling incomprehensible fragments.” Shibli shuts us out of the girl’s psyche in a radical act that underscores the idea that representation can only extend so far. In other words, while Shibli, a Palestinian living in the West Bank, is in a position to represent trauma that, to a certain extent, is her own, she refuses to venture into the headspace of this Arab Bedouin girl. By not speaking for her, Shibli highlights that the girl’s voice cannot be retrieved. What has been lost is lost forever and can never be restored — the girl “will forever remain a nobody whose voice nobody will hear.”

This isn’t to say that the horror of the crime is not made plain. The abuse she suffers is painfully recounted: she’s stripped and hosed down in front of the camp; soldiers go in and out of the hut to assault her; and on the morning of August 13, she’s taken out into the desert and shot: “Blood poured from her right temple onto the sand, which steadily sucked it down, while the afternoon sunlight gathered on her naked bottom, itself the color of sand.” The voice used to speak of these acts is chillingly sterile and carries a haunting precision, as when the commander rapes her:

With his right hand covering her mouth and his left hand clutching her right breast, the bed’s squeaking drifted up over the stillness of dawn, then increased and intensified, accompanied again by the dog’s howling. And after the squeaking finally ceased, the loud howling outside the door continued for a long time.

This dog, this anguished dog, is a fixture in the novel. Itself a minor detail, the dog stands witness to all the atrocities the soldiers commit, its sounds of distress serving as an ineffectual protest to the girl’s pain and degradation. Indeed, if we, as readers, are to identify with any character in the story, surely it is this dog, standing apart and outside of the girl’s experience, unable to do anything but howl.

In the second half, the dog returns as a spectre, haunting the woman — “the dog’s barking continues to echo in the air until the last hours of morning; sometimes the wind carries it closer to me, and sometimes further from me” — and eventually urging her to undertake a risky journey to uncover more about the crime that took place a half century before. In an ending as abrupt as it is infuriating, we come to understand what Shibli is telling us, which is that where justice and restitution are impossible, the dog’s howling not only constitutes a call for past atrocities to be remembered but is also an anguished cry of futility. It is a howl against both a history that cannot be recovered and a “no less horrific” present that remains unchanged.

On August 13, 2020, 71 years to the day after an Arab Bedouin girl was shot and buried in the Negev, the United Arab Emirates announced normalization of relations with Israel, soon followed by another Gulf state, Bahrain, and with endorsements from a third, Oman. These agreements occur against a backdrop of continued annexation of the West Bank, the bulldozing of homes, and bombardments of a Gaza awash in suicides. In short, there is no longer even the illusion of Arab state unity and support for the Palestinian cause. In State of Siege, Mahmoud Darwish writes, “Only when life gets back to normal again | can we grieve like everyone else over personal matters.” Shibli’s novel is a searing admission that return is impossible. There is no normal to get back to.

When injustices are so large and anguish so all-encompassing, maybe all that’s left is to howl at minor details.

Gran reseñas del libro.

Desgarradora está novela como con todo lo que sucede en Palestina.

Lástima que no tengamos más libros traducidos de Adania