Line 19 – Mount Scopus to Mahne Yehuda

Sulafa Zidani

I took Bus 19 frequently when I studied for my MA in Jerusalem. My first stop was on Mount Scopus, הר הצופים – the Mount of the Onlookers, or perhaps The Mount of Surveillance, the main campus of my alma mater, the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. In my China Studies program, I was the only Palestinian in classrooms full of IDF soldiers.

When my friend Rachel visited from the US, she remarked that the campus looked like a stone spaceship that landed on our planet. Out of place, indeed, my university on our stolen land.

At the amphitheater behind the law library, you could cast your gaze all the way to the shores of the Dead Sea.

Step off campus and you find on one side the Mount of Olives, جبل الزيتون Land seized in 1967 and converted into a military base. And on the other side, a microcosm of the Israeli carceral state: the heavily policed neighborhood of Isawiyya.

In a few stops, Line 19 rudely arrives in Sheikh Jarrah. It makes fewer stops in this East Jerusalem neighborhood that now the whole world knows.

I’ve been to one of these homes once. I must have been 18 or 19 when my activist friends took me along to visit a house half-occupied by settlers. The Palestinian family lived in the other half. And this was supposed to be “ordinary.” We sat and shared tea. Mostly quiet like in a vigil.

Line 19 then crosses the freeway that slits “East Jerusalem” from “West Jerusalem.” The bus drives by Jerusalem’s downtown, where I once encountered a swarm of settler youth chanting “death to Arabs!” waving Israeli flags to mark “Jerusalem Day,” the day in 1967 when Israel completed the occupation of the eastern part of the city. My roommate grabbed my forearm and pulled me to an alley. We hid there for a while until the crowd looked smaller and the chants less audible.

The bus passes by an Italian hospital, an Ethiopian church, and the Anglican school my brother briefly went to before my family returned to Haifa. When I asked his white European school principal what made her decide to live in Jerusalem, she said Jesus had called on her to do so.

I lived in so-called “West Jerusalem,” near the Mahne Yehuda Market that I frequented on my way home to get inspiration for cooking and to be interrogated about my ethnicity. Can I just pay you for the tomatoes on the vine and keep moving?

This was a predominantly Jewish neighborhood. At first, my landlord, Nissim, a middle aged Yemeni Jewish man, did not want to rent to me. Fine, I retorted. I didn’t want to give my money to a racist anyway. But the Israeli filmmaker who was breaking his lease to move out was desperate. So, Nissim agreed to interview me. This involved me taking a train to Tel Aviv where I sat in Nissim’s home with his wife and sister. “My sister is intuitive” he told me “she looked into your eyes and she saw that you’re a good person.” I wondered if she could sense that they made me feel unsafe. “But,” he added, “you can’t have an Arab roommate.”

I told Nissim I wouldn’t beg him, and that he either counts on me or he doesn’t. “Fine,” he said, “but your name has to be the only one on the lease.” I lived there for two years, and Nissim started lying to me and to himself. “You know it was never me, but the neighbors…they didn’t want Arabs in the building.” Nissim began to see himself as a peacemaker and hero. I brushed it off. What’s the point.

Line 940 – Jerusalem-Haifa

Walking distance from my apartment in Mahne Yehuda was the main bus station in Jerusalem. Here, I could conveniently escape this abusive city to return to my Mother’s in Haifa, to breathe the air blowing in from the open horizon of the Mediterranean Sea, and to eat some of my grandmother’s food.

I usually took the bus on Thursdays, since the Israeli weekend is centered around Shabbat (Friday night till Saturday night, there is no public transportation and everything is closed). Thursday also happened to be the day many soldiers got to go home for the weekend. Regardless of your age, gender, or cuteness, these soldiers would aggressively shove you aside on their way in. I missed the bus at least twice because of this. I told myself that I had to make my elbow game strong. Once, a soldier tried to flirt with me. Honestly, I have nothing else to say about that. I shut it down pretty quick.

Line 940 took the new freeway called Highway Six, much of which Israel built by seizing Palestinian olive groves. The same type of olive trees whose bountiful harvest provides the olive oil my dad sends me once a year in recycled Coca Cola bottles all the way to the U.S. I am still not sure if this is just his way to say he loves me, or if it’s his way of reminding me to stay connected to the Palestinian earth, to our culture, and to our clan. The Zidanis are a proud bunch, I’ll tell you that. We love reminding people that we are descendants of Thaher el Omar el Zaydani, an independent Palestinian leader who resisted Ottoman rule.

The bus lurches to a stop at the main terminal. And like many of the buildings in the area, the terminal was there because the British decided. At least it was next to the sea.

Line X – Haifa to Beirut?

I usually spent my weekends in Haifa, doing laundry, eating my mother’s food, and hanging out with my sister and friends. Then I took line 940 back to Jerusalem to get ready for another week of school.

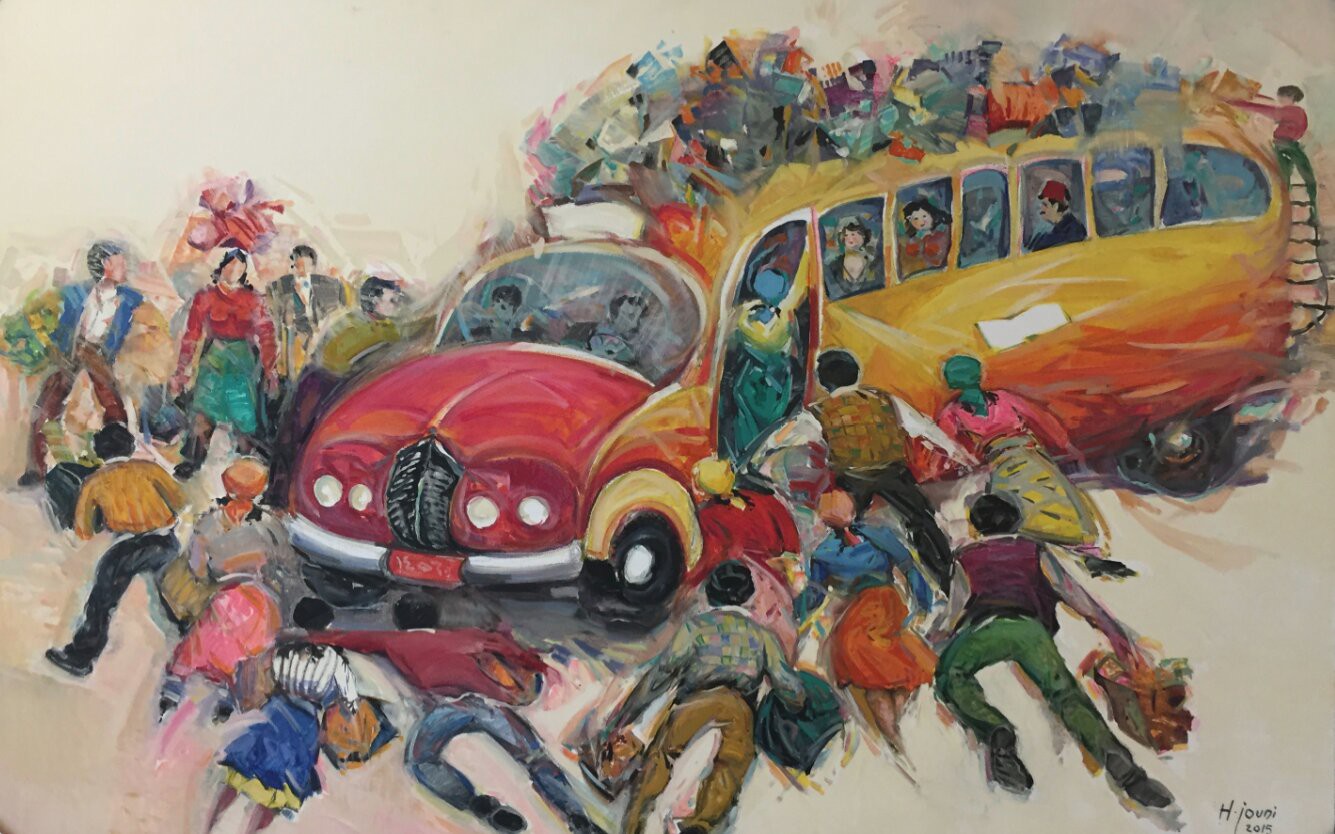

But this is a bus line that I’ve never taken. Images often circulate of this bus line between Haifa and Beirut, or other bus lines that, for now, no longer exist: Kuwait, Lebanon, Syria, Palestine. My generation has never been on this bus ride, but it is part of our past, and, living in the uncertainty of the present, the future we nostalgically dream of.

My Uncle Hameed used to drive to Lebanon all the time in the late 1970s. Auntie Fatima, who became his wife, lived there after her family was displaced in the 1948 Nakba. While we sip coffee in my father’s village in the Galilee, Auntie reminisces to us: “Yes, I would sit on the swing outside my house every weekend waiting for Hameed to come see me.”

Last week, I was talking to a mentee who has family in the West Bank and Gaza. She asked me what the oppression of Palestinians looks like in Haifa. We are all oppressed differently; like our towns, our dispossession is fragmented. Cut off.

My British stepsister was in Beirut during the Second Lebanon War. She had been taking Arabic classes at the AUB when the war broke. Months later, my Israeli college friend Shai would tell me he can’t sleep because he still has nightmares from his military service during the war. Sadly yet unsympathetically, I responded: “That’s what your government does to you, Shai, and you have choices.”

My grandpa and his cousin went to a boarding school in Lebanon in the 1940s. In 1948 they came back to their village Jish to check on their family. They found them all massacred and their house in ruins. His dad, Radwan. His mother, Sharifeh, who was pregnant at the time. His two sisters, Khadra and Mariam. And his two brothers, Grandma said she will check in the cemetery to see what their names were next time she’s in Jish. He and his cousin were the only two left. Why did I only hear about this in 2009, six years after my grandpa’s death?

On the outskirts of Jish, there’s a hill called تلّة الصرخة—Screaming Hill. Since the village is close to the Lebanese border, families who were partitioned by the war would go to that hill and scream to each other from across the border. What were the conversations that could never be uttered on Screaming Hill?

I want bus lines that connect our bookstores, our record stores, our artists. I want to commute from my home to a film debut or music show. I want bus lines where people won’t move seats when they hear me speak Arabic.

I want to ride a bus without soldiers, without the remnants of scorched and uprooted olive trees — bus routes that Uncle Hameed could take to visit Auntie Fatima on the swing. I want a bus that connects home to Palestinian home, a bus that traces over the fragmentation, and sketches out the fullness of the land I call home.