Viola Shafik

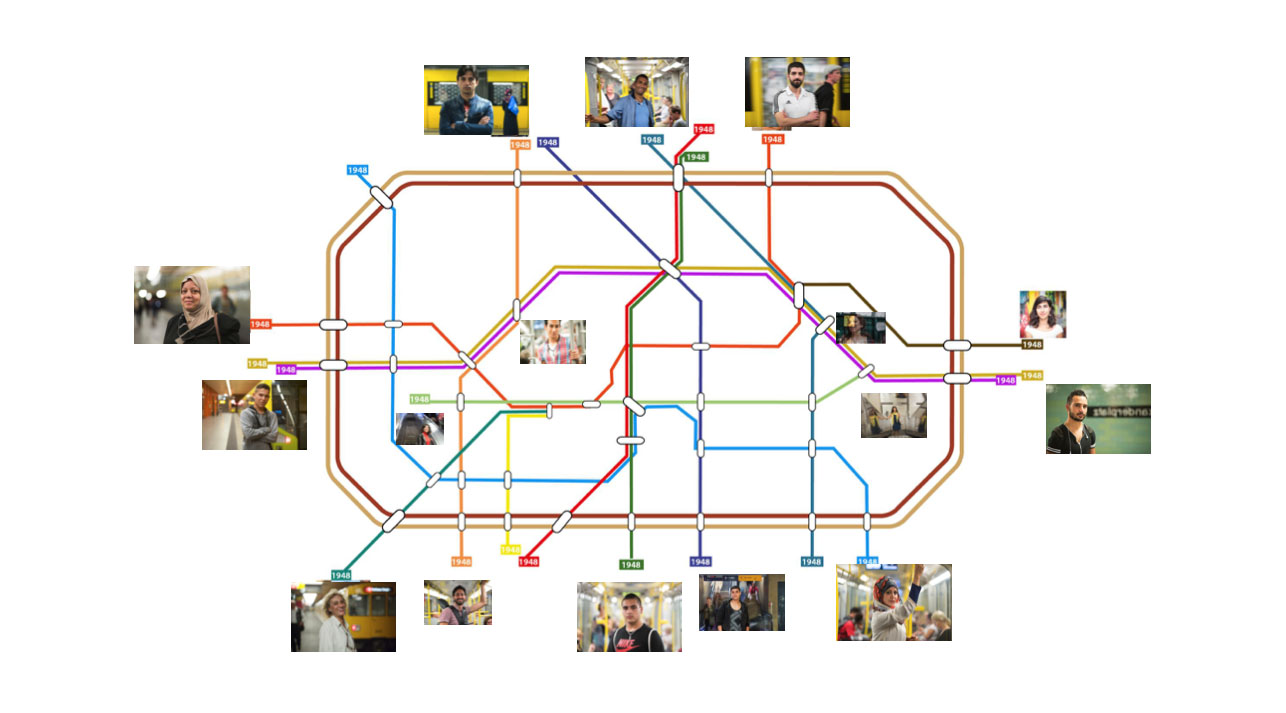

Imagine you are looking at this Berlin subway or U-Bahn map and you’re seeing all these faces who are ascribed to different neighborhoods of the city. Why U48? Such a number does not exist in the Berlin subway system, it is a chimera.

The number rings a bell, of course, for Palestinians. It is the year of the so-called Nakba; 1948 evokes the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Palestinians from their homes and the destruction of innumerable villages. And those who remained behind have come to call themselves “’48Palestinians.”

In the accompanying text and U48 portraits you read: “We, who are unable to meet each others in our homeland, here we meet easily; me, who stems from Haifa, she, the Palestinian woman born in Berlin, and he, who was raised in the camps of Lebanon and Syria.

The subway line has become a map of our homeland.”

Mohamed Badarne’s U48 was presented in 2016 in the framework of “After the Last Sky,” an event organized by Kultursprünge im Ballhaus Naunynstraße, during the group exhibition “Questioning the Chroma-Key Principle,” which took the cinematographic technique of chroma keying (“green screen”) as the starting point of its investigation. It explored the “paradoxical dialectics of the ‘Present-Absence’, which occupies a pivotal place in the Palestinian situation” because, according to the organizers, in “the Zionist imagery of the country as a ‘land without people’, a so-called no-man’s-land, the existence of the Palestinian population has been negated since at least 1947/1948, enabling the violent rewriting and occupation of the place.”

Badarne’s photographs project the complex cartographies of exile and return and hence “intervened against future disappearance” and can in fact “be interpreted as ‘small-scale resistances’ against the status quo of the dominant regime of visibility, because they recover what has been forgotten, and uncover what has been buried,” as “Questioning the Chroma-Key Principle” notes.

Badarne, photographer, trainer, and human rights activist was born in the Palestinian village of Arraba, in the Galilee and moved to Haifa at the age of 18. He got involved in social activism as a teenager, volunteering in refugee camps and cofounding a human rights organization for Palestinian youth. Until 2012 he earned his living as a high school teacher and NGO worker. Since then, after graduating with a degree in Professional Photography, Bardane has dedicated his career to photography and teaching photography in NGOs, community centers, and to independent groups. He soon became acclaimed for his photographic oeuvre, and has received grants from several renowned art foundations. His work has been presented in diverse venues, such as Darat al Funun Art Gallery in Amman, the Fusion Festival, the European Center for Constitutional Rights (ECCHR) in Berlin, the International Labor Organization (ILO) in Geneva, and the UN Headquarters in New York among others. It has been included in the collections of the Khalid Shuman Foundation and private art collectors. As a curator, he was responsible for “People of the Sea,” the opening exhibition of Qalandia International art festival in 2016.

The launch of Badarne’s career as photographer coincided with his moving to Berlin in 2012. What triggered this change of place?

Certainly the general limitations and alienation which the so-called ’48 Palestinians experience was one of the main factors, particularly the feeling of being a stranger in one’s own land and the highly restricted and minimal possibilities for professional and cultural development and exhibition for Palestinian artists in Israel. Marginalization and Arab labor conditions became thus one of the artist’s main concerns, just to name his impressive photo series “Come Back Safely.” Through this series, Badarne attempts to give visibility to Arab workers and their labor conditions in Israel. He also included portraits of families who had lost one of their members while working there.

Some of Badarne’s projects are of international scope, such as his African Descent about people of color all over the globe, Acid that beautifully pictures female victims of acid attacks in India, and most recently The Forgotten Team, a photography exhibition in solidarity with all 2022 FIFA World Cup workers.

Badarne’s visual storytelling project puts the spotlight on the lives of migrant working people who have been laying the groundwork for the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar. Without them — the forgotten team — this mega sport event with all the new stadiums, hotels, and transport networks could not have taken place. Thousands of men and women from Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Nigeria, Pakistan, and other places set out to make a better living, but they have encountered harsh working conditions and even death. Thus, over five years, between 2017 and 2022, Badarne visited Qatar and Nepal several times to meet with workers and their families, and to capture their stories and the injustice they suffered. It shows them in Qatar – at work and in their private space – and after their return home. It also portrays families whose loved ones died there, as well as local initiatives that seek accountability and compensation.