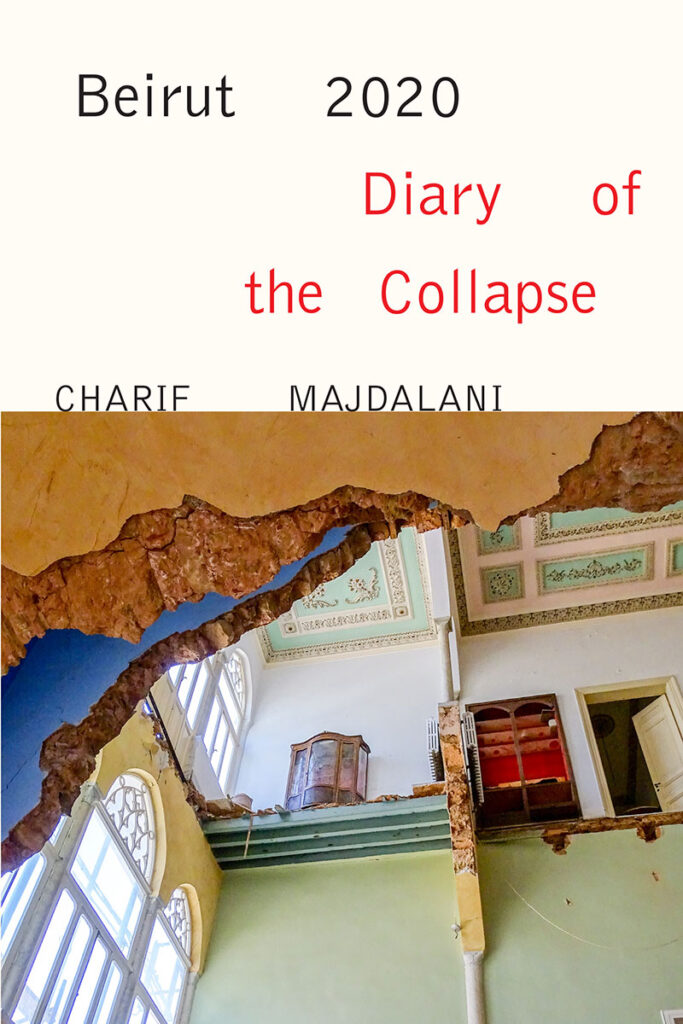

Beirut 2020: Diary of the Collapse, by Charif Majdalani

Penguin Random House

ISBN 9781635421781

A.J. Naddaff

For more than a year, I’ve scoffed at the idea of reading a book about the pandemic. It seemed almost wrong, perhaps too soon, to have a literary account of Covid. Are authors who have published pandemic books exploiting the world’s flames for their own success? For these reasons, I was reticent about reviewing Charif Majdalani’s Beirut 2020: Diary of a Collapse, which focuses on the intersection of the Covid pandemic with a Lebanese twist, zooming in on the myriad other calamities that have devastated the country over the past two years.

I avoided the book because I, like so many Lebanese I know who write and consume news in English concerning the country, feel like we have read all about the “collapse” we are living through. At least one of its many synonyms — meltdown, deterioration, disaster — appear in nearly every piece. Besides, no words, no matter how descriptive, can entirely depict the lived experience. While a profusion of good stories have come out over the past two years, rarely do I find reports that stretch language out of its skin, creating a new lexicon for the collective trauma we’ve become inured to. So often writers become agents of the words, flexing their linguistic muscles to reproduce the same vocabulary from a stockpile of hackneyed sayings.

So, how does one avoid writing about the “resilient Paris of the East” without regurgitating one of its thousand clichés? Majdalani turns to the personal. We follow him as he writes about the mundane and absurd details of his life in Beirut:

When I got home, Mariam announced that the washing machine was making a weird noise. And indeed, the noise was disturbing—a kind of regular clacking, almost rhythmical, to the beat of the rotating drum. I had actually just gotten it repaired a few days ago, the day before yesterday in fact. So I called the repairman, who didn’t answer, of course. These details of daily life which are out of our control are frustrating and make me angry. It’s easy to get angry these days.

On social media it’s always the same thing, inexhaustible, ad nauseam: economic collapse, the bankruptcy of the country, capital control, exchange rates, the pound in free fall, inflation, and penury lying in wait for us all.

He spends his days running into banks to convert dollars into pounds, listening to his teenage daughter about her desires to immigrate; we observe police officers ironically controlling the one place where traffic lights work in a country lacking electricity, “as if they were vengefully making a point of reminding us that order no longer reigns.”

In another scene, we are given access to his interactions with a burly repairman who has come to fix the air-conditioning units and is embarrassed to respond to how much the bill will cost, positing “like a little boy caught being naughty by his teacher.” Not only is the repairman hesitant about asking for money because the inflation has made the sum so enormous, but also because Majdalani’s wife, Nayla, a psychotherapist, used to counsel him for free about his son’s problems. As we read, there is an immense voyeuristic pleasure gained in the awkwardness of the situation, like we are peeking through a window ourselves into the absurdity of a 2019-2021 Lebanese life.

The negotiations with the repairman are disrupted by a pigeon who lands on the terrace railing, which pulls Majdalani’s distracted mind into a literary digression. He starts thinking about the 1938 novel by Claude Simon titled The Palace, and the “description of the magical transmutation of a pigeon on a windowsill.” Suddenly, he is brought back to earth by the repairman who declares they will soon be so hungry that they will eat pigeons. And here, we are let into another distinctly Lebanese moment:

“I replied that it would be a while before that happened, that we were too proud for that.”

Majdalani could have just said that Lebanese are proud to the point that it does more harm than good. But this is well-known. As the writer Khaled Hosseini has said, the fact that clichés are clichés is because they’re dead-on and therefore their aptness is overshadowed by the nature of their saying as clichés. Another example of Majdalani’s confessional intimacy takes the form of letters written by Najla, which he includes. In a peculiar exercise, she engages in a sort of self-therapy — “for herself, and with herself,” where she jots down every day a session where she is both the therapist and the patient. I am reminded of how my own Lebanese therapist quit his job suddenly with no warning, perhaps because he could no longer deal hearing with the boundless hopelessness and exhaustion. Instead of choosing for the easy route, Majdalani, as an astute observer, jots down the minutiae that elucidate further just how bad the situation in Lebanon is.

The journal’s linguistic freshness is also striking. Written in French, translator Ruth Diver makes us feel the difference of Majdalani’s literary tongue. Yet Diver does not force the testimonials to sound too foreign. As readers of English, we are transported into the Lebanese francophone world of Majdalani, the professor of French literature at the Université Saint-Joseph in Beirut. This is just an assumption since I haven’t read the French original — perhaps Majdalani’s French text is not as dazzling, and the credit should go to the artistry of Diver as translator. At the very least, it provokes interesting questions about the long-list of Lebanese novelists who write in French and how their diction and style differs from those who write in Arabic or in English. Of course, the nature of writing in French (or English) for that matter is that there is more liberty in a country that already exercises relatively more press-freedom than other countries in the region. But I wonder, if Majdalani placed as much blame on Hezbollah, “the most dangerous” of all parties, in an Arabic text, would he get away with it? The tragic fate of Lokman Slim, a prominent Lebanese critic of the militant group that was recently assassinated, leads us to think otherwise. It is the freedom of Majdalani’s political confessions that also brings some of the same voyeuristic pleasure I described earlier, albeit different.

Where the account falls short is when it looks or sounds too familiar, as if I’d already read the sentence in a news piece — except here we are reading literature. I must be honest and say that my bias is as someone who is an avid consumer and participant of Lebanese media. There are very good explanations in the accounts of contemporary Lebanese history. His tone is reflexive and magisterial, providing a genealogy of that history to the layperson: the past 30 years are packaged and told as a teleological riddle to be solved. For 30 years, before the war in 1975, Lebanese also lived roaring decades that were met with the same fate: collapse. Now, in looking back on these past three decades, marked by the end of the war, the savage privatization and reconstruction farces, where “nothing was produced, agriculture was abandoned, industry was nonexistent, people lived on imports, and the government decided to borrow US dollars from the local banks at absurd rates, in order to finance large-scale projects,” we understand why hindsight is always 20/20. For Majdalani, current events are a form of déjà-vu: “Once again, we were dancing at the foot of a volcano whose threatening roars everyone refused to hear, or on the edge of a precipice into which we finally fell.” Yet of course, these past two years have been different on so many accounts, especially as Lebanon witnessed a dash of hope with the massive uprising that engulfed the country in October 2019 before its infernal descent.

In the part on the revolution, Majdalani intersperses a political account with a personal anecdote. He is having dinner at the terrace with friends and recalls the last time they met here was on the eve of October 17, 2019. Days prior to the popular uprising, massive wildfires spread throughout the Mount Lebanon region. Conflagrations are not too uncommon in the summer time because of the heat and lack of rain. But the long burning exposed once again the utter incompetence of the state which had bought aircraft to extinguish fires but had parked them at Beirut’s airport with no money to maintain them. So fires raged and fuel-less helicopters remained parked, while Lebanon had to call on its neighbors for help.

Lebanon’s collapse then started with hope. That’s partly what makes it so lamentable. If 30 years is a symbol for the Sisyphean cycle of despair, then wildfires (and WhatsApp taxes) represent revolution-turned-collapse. The diary foresaw what many Lebanese viscerally felt: the August 4th, 2020 port explosion that turned the city upside down, bifurcating all that came before and after. It was as if “the entire collapse I was describing was not happening fast enough… some unknown malignant force decided to precipitate them and in a matter of seconds hurled everything that was still standing to the ground.”

I was not in Lebanon when the explosion took place, but so many friends and loved ones were that I sometimes feel like I had experienced it myself. Reading an account of what happened that day — once again but from Majdalani very detailed perspective — filled me with extreme anxiety. I would not recommend any Lebanese read it, especially those who lived through that horrific day that has been blotched in our collective memory. This is my trigger warning to you. For an outsider, it provides a human perspective of what happened and another testimony, once again, of how bad the situation is. 15 months later and the victims of the families of the port explosion still have no semblance of justice that has turned both politicized and superficially sectarian. The same war criminal politicians continue to stoke sectarian conflict while chortling around a mezze table.

While we are confessing, I must admit that Diary of a Collapse changed my mind on the futility of writing a Covid-Lebanese absurdity novel. I’m not the first to have said that the best fiction, after all, reflects reality. I now started writing my own diaries. Here is one entry:

On Thursday, October 20, I am sitting in Café Younes, tucked behind Hamra Street, with Lebanese novelist Rachid el Daif. It’s fall and the orange and lemon trees mask any remnants of the sunny day. Everything is relatively normal in the café, the longest surviving coffee roaster in Lebanon. It’s the same branch that my dad came to appreciate for its Turkish coffee laced with cardamon the first time he visited me two years ago, when the currency was still somewhat stable. I am preparing Rachid for an interview when our phones start buzzing. Sectarian clashes 15 minutes away have broken out on the same infamous frontline that divided the city into two during the war. People start packing up; a look of worry marks the face of a woman whose toddler accompanies her in a baby carriage. Rachid tells me to go home and not to leave the house. We get up to depart. But before, he gives me advice: “Study closely these events, read the news and immerse yourself in the local politics. These are the details that will make your book stand out.” It sounds intuitive, but it’s something I’ve neglected recently.

These words — on the importance of actively bearing witness — were understood and translated much earlier by Ghada Samman in her accounts of Beirut’s war which she documented in the form of nightmares. Or, as George Saunders wrote recently to his students on writing about “the hard, depressing and scary time” that is Covid: “there’s still work to be done, and now more than ever.”

Samman, Majdalani, El Daif, Saunders — the writers around the world are of the same mind when it comes to recording. Now, in this precise state of overlapping collapses, we need writers more than ever. I owe thanks to Diary of Collapse for changing my once-pedestrian thinking.