Samir El-Youssef

On the 12th of June, 1982, I realized the simple yet searingly painful truth that Mother didn’t give a damn about us. It was on that day (and how could I ever forget that day?) Father had a heart attack and died.

We were running, the three of us, Father, my brother Ziad, and I, when he stopped in the middle of an utterly barren area. A few moments later, Father dropped to the ground. Ziad and I watched him writhing. Soon after, we came to the conclusion that Mother did not care about us one bit. It was I who first reached this conclusion, after which I made sure that Ziad was in accord.

“She hates us.”

“Who?” he asked innocently.

“Who? Don’t you know?”

Now, when I remember it all, after so many years, I realize Mother’s attitude was not altogether a surprise. I’d always suspected that she preferred her brothers to us. However, I’d never imagined she preferred them to the point that she was willing to put our lives at risk, simply to ensure that they didn’t feel more worried or lonely than they would otherwise or, on that cursed day, that we would be sent to join Uncle Rasem and his family, and possibly Uncle Nabeel, who, for some strange reason, our bloody mother was certain would be there, too.

“Is he so stupid that he would return to Lebanon as things are?” Father had tried to reason with her.

“You don’t know Nabeel, you don’t know my brother,” she replied, her voice ringing with pride, which was an added aggravation when my brother and I could feel only fear and anxiety.

It was the first week of the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, and like most people we thought it would be safer to remain indoors. Mother, however, took things a step further and insisted that the three of us go north, to Uncle Rasem in Beirut.

“It’s safer there! When the Israelis come, they’ll arrest the men,” she admonished me when I protested angrily. “All the men are running away. You must get away too. Your uncle will look after you!”

I didn’t believe what she said, neither did Father nor Ziad, and so she tried a different approach: she said she was absolutely sure that our lives were in imminent danger. “It won’t be long,” she went on, “before the Israeli army secures control of the town, with soldiers ordering people to gather in the squares, where they’ll be interrogated and detained and possibly shot.”

Though knowing full well that we were scared stiff, Mother didn’t seem to mind making such terrifying predictions as long as they served her intention; and of course that is what must have contributed to our long-lasting hatred of her. The rhetoric she used, too: “I have it on good authority”— yes, she used words which one could never imagine a mother using — “the Israeli army has been carrying out large arrest and detention operations in towns and villages where their forces have established control.”

Father, in his turn, and probably provoked by the very expression on good authority, dismissed all that as mere rumor. In the hope of persuading her to give up her intention of sending us to Beirut, he concocted a few rumors of his own. He claimed that the Israelis had already reached the outskirts of Beirut, so there was no longer any point in trying to flee to the capital.

“Rumors! Sheer rumors!” she replied with a sneer, emphasizing that she was absolutely sure that the Israelis would take several weeks before they reached anywhere near Beirut. She was right, but that was not the point. She wanted us to go to Beirut and stay with her brothers so that their being surrounded by family would reassure them. My father knew this very well.

“You’ll be safer with your uncle!” she told Ziad and me whenever either of us objected, and even when we didn’t. She seemed to enjoy repeating herself just for the sake of it. Indeed, she enjoyed repeating any sentence in which her brothers were mentioned. A sudden joyous tone took over the moment she mentioned them, regardless of how casual or banal the context.

“You’ll be safer with your uncle!” she said while Father made a last attempt to make her see sense.

“There won’t be any taxi driver mad enough to take us all the way to Beirut,” he pointed out.

But Mother had already thought of that; she had arranged for us to be taken to Beirut by a neighbor who had decided to leave the area that very afternoon. I couldn’t help suspecting it was she who had convinced the neighbor that it was safer for him and his family to leave. I think both Father and Ziad had similar suspicions. But the neighbor had no vehicle other than the pick-up truck he used for work, so now we had another reason to oppose her plan.

“Yes, he has a truck.” Mother pretended not to understand the problem. The three of us grew more annoyed.

“Do you want us to go all the way to Beirut in a pick-up?” Ziad cried out, astonished that Mother could be so inconsiderate.

“What else can we do?” she replied, trying her best to sound helpless, but barely concealing the smell of victory; the argument was now over the trivial matter of means of transport. “I tried to hire a taxi but none was available,” she hurriedly added in that feigned sense of helplessness.

“You tried to hire a taxi before you even asked us?” Father protested, not that he expected either an explanation or an honest reply.

“I don’t want to go,” I cried out. I didn’t mean it, but I wanted to support Father.

“Neither do I,” Ziad added his voice to ours.

Mother made no response, falling silent in a manner that made it clear that our fate had been sealed and no more was to be said.

Remembering it now, after nearly 22 years, I find myself reliving the moment when I felt I wasn’t looking at a mother but at a heartless stranger who had coldly orchestrated everything so that we had no option other than the humiliation of getting into the back of that pick-up and being driven away to meet our frightful destiny. For at the very moment she fell silent, we heard the sound of a horn blast coming from the front of the house, from the very pick-up in which we were to be carried away.

I recall as if it were yesterday how we were in effect pushed into the back of that pick-up, but what I recall most is the look of satisfaction on my mother’s face as we were driven away. It was the look of someone who had suddenly managed to get rid of an obstacle to the peaceful days, to the days before the Israeli invasion, but probably also to the long gone days before any of the three of us came into her life.

But, to be fair, Mother wasn’t the only reason we left on that June day in 1982; it was fear, too. We were frightened, knowing that she had seized the opportunity to send us away.

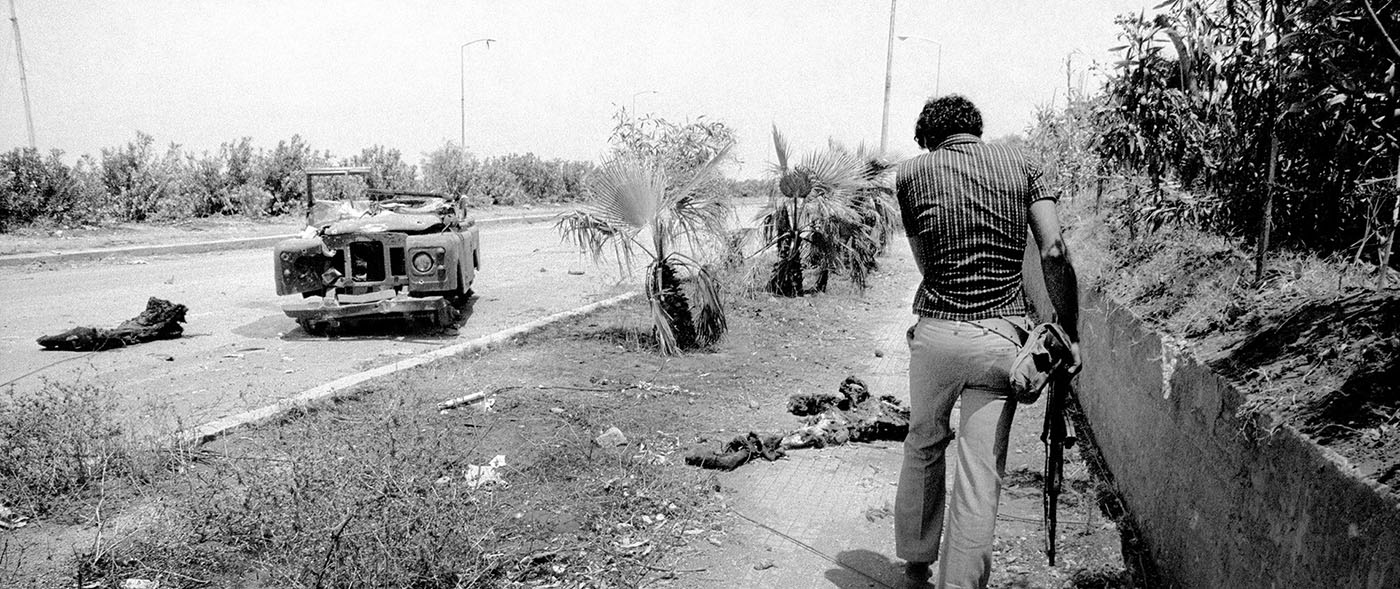

The military invasion had taken over every aspect of our lives. There was no way to ignore or forget what was happening unless one was lucky enough to grab a few hours’ sleep. Israeli F-15s and F-16s roamed the sky all day long, there was continuous shooting and shelling, and whenever one dared to look out the window, usually peeping out through drawn curtains, there were tanks and army vehicles. We were under military occupation and throughout every waking moment we were so frightened that after all these years I remember it as vividly as if it were happening now.

To be honest, we were so intimidated that when Mother first suggested we go, I believe we must have felt grateful until we realized the truth behind her suggestion. For what it’s worth, such a suggestion must have engendered the only sense of relief in our daily existence, which was overshadowed by images of our ashen faces and long stretches of tense silence. No one dared to break such a silence, not even to make a comforting statement of any kind. We were so silently frightened that now, as I sit here thousands of miles from where it all happened and after some 22 years, I cannot remember anything that was said or done without recalling the whisper of fear that accompanied that time. Fear reigned over every minute of our lives and made us forget what we normally liked or disliked.

I recall in particular how one afternoon Ziad ate a whole bowl of a dessert that he’d never liked before. He emerged from the kitchen holding in one hand a bowl of rice pudding and in the other a spoon. He had already started devouring the pudding and had the expression of someone who had always eaten and enjoyed this particular dessert. We sat there staring at him. None of us said anything till he’d finished, not because we thought it was funny, but because we were so engrossed in our own worries that we didn’t think it was worth mentioning; if fear had made Ziad forget what he hated, it had also left us devoid of any sense of humor. When Mother eventually reminded him that he was eating something he’d always detested, it wasn’t said as a joke but as a reproach. Watching him enjoying his food, she probably assumed his usual dislike of her rice pudding had simply been a pretence intended to annoy her.

When Ziad had finished, he tried to make a joke of it.

“I wish you’d spoken earlier!” Ziad said, smiling and looking at both Father and me. “I honestly didn’t know what I was eating,” he added after a while, and then the smile vanished and he got up and left the room. We knew he was about to cry.

No, Mother didn’t force us to leave that day, but she manipulated our fear to have her own way. This is what makes my memory of that episode and of Mother so bitter. Except for her, we were all frightened. She was worried yet didn’t seem afraid. She worried about her brothers, both of them: the one who was living in Beirut and the other one who had been living in Germany.

“I understand why you’re worried about Rasem and his family,” Father told her. “They’re in Beirut, and fighting around the city is getting worse,” he said, referring to battles between pro-Israeli Lebanese militias on the one hand, and anti-Israeli Lebanese and Palestinian militias on the other. But why do you worry about Nabeel?”

She herself had often enough told us how happy Uncle Nabeel was living in Aachen, married to a German and with a child, all of which meant that he was far from danger. But no, now, in her mind, Uncle Nabeel must have left the safety of his life in the relaxed town of Aachen and returned to Lebanon.

“But how do you know that he is back? Who told you?”

“I know my brother,” she insisted. “If he hasn’t come back already, I’m sure he’s going to take the first plane to Beirut.”

“But why on earth would he do that? He’s not mad, is he?”

“No, he is not mad. Of course he is not mad!” She was getting angry. “You don’t know my brothers. You don’t know what a sense of loyalty they have. Nabeel will come back to be with his brother, to be with us, and it might surprise you to know he’d want to come back to join those who are fighting the invasion.”

“Sense of loyalty?” Father suspected that Mother had herself gone mad, but he kept on reasoning with her calmly. “You do realize that the airport is closed?”

“He’ll find a way. He’ll come through Syria; I know my brother.” She insisted that Uncle Nabeel was too politically committed to stay away. Mother had never before mentioned my uncle’s so-called political commitment.

Enjoying a quiet life with his wife and child, Uncle Nabeel, however, wasn’t entertaining even the slightest thought of coming back at that time, or even at a less dangerous time. Years later when I visited him in Germany and told him how he’d been expected to come home to fight, he laughed his head off and translated for his German wife what I had said. Then they both laughed and said they must tell their friends about it.

I nearly joined them in considering the story of Mother’s baseless worry over her brother in peaceful Aachen a joke, and nearly laughed with them, but in the end I didn’t. Nothing that Mother had done, particularly during the day she sent us away, was funny. Watching them finding her innocent concern, as my uncle put it, a cause for merriment made me feel like telling them what had happened after we were pushed into that pick-up and sent to face our fate on a long hike through scrubland, in the midst of an ongoing war. “It’s not funny. Father died because of her innocent concern,” I wanted to say.

I recall it now while I am looking out the window of my flat, which overlooks Highgate tube station. I recall sitting in the pick-up truck, sweating and breathing heavily under the glowing June sun, though I don’t remember exactly how long it was before the vehicle stopped and the driver announced that he wouldn’t go any further. “It would be suicidal to continue while the fighting is going on,” he said. “We’d just be driving into the battlefield.”

“There can’t be fighting everywhere. There must be some safe areas we could cross?” Father tried to persuade the driver. “I promise you I’ll make it worth your while once we’ve reached Beirut.”

But he wouldn’t budge. The only place he was willing to drive us to was back home. “I’m going back. It’s wiser to take the risk of being arrested by the Israelis than to be caught in crossfire.” He added, “I’ll surrender to them if necessary.”

“Let’s go back,” I urged Father, encouraged by the driver’s attitude.

Though Father had never been keen on the idea of going to Beirut, he nevertheless couldn’t go back. He couldn’t go back to face Mother’s disapproving look, and she could give you the kind of look that made you feel you were useless and doomed to fail for the rest of your life. So he went on pleading with the driver. But the man had made up his mind; he wouldn’t go any further even if he were paid all the gold in the world.

“You should listen to your son and go back,” he urged my father, “and if you insist on taking your chances and decide to carry on, allow me to at least take the boys back with me.”

Father couldn’t look at the man. He was so angry. I thought that if the driver dared say one more word Father would hit him. The driver must have realized this, as he quickly got back into his truck and drove off.

We stood there not knowing where to go or what to do next. It was up to Father to decide, but in that situation the three of us were equally helpless. In the midst of that dusty road in no man’s land, and under the burning sun, it was too early to hope for a cool breeze and too late to try to reach the nearest town before dark. We stood there silently, feeling so powerless that hating someone was all we could do. Mother was the obvious candidate for such an emotion. I hated her then, and I have never stopped hating her since.

“I swear to God that she’ll never see our faces again!” Father muttered, out of the blue, in a bitter tone that was alien to him.

“Never!” he repeated, looking at us as if he were trying to gain our endorsement for his sinister intention.

“Yes, yes!” I confirmed, and wanted to add I hate her, we must all hate her. I looked at Ziad as if to urge him to agree, but poor Ziad looked as if didn’t know what was going on.

“I’ll take you away from her!” Father said, staring at us, and I nodded.

We were still standing there, waiting for him to decide on our next move. Eventually, and as if to avoid choosing between going forwards or backwards, he strode towards a winding pathway that led to nowhere we knew. But as if to assure him that we completely trusted his sense of direction, Ziad and I followed him without hesitation. We sensed that he was unwell and we didn’t want to linger there arguing with him. He began running, and we did the same. He did not stop, nor did we, even when we found ourselves climbing a steep hill.

Yet a few moments later, Father seemed surprised and disappointed that he had chosen this particular route. Now he stopped and gazed in different directions. “Her brothers! That’s all she cares about!” I heard him mumble. I was standing a few steps behind him. I felt he was so frustrated that he no longer knew, or even cared to know, where we were going. He was angry and was breathing heavily. He took a few steps forwards. “She’ll kill us all for the sake of her brothers,” he went on bitterly, an expression of utter despair on his face.

Ziad and I exchanged worried looks, suspecting that he’d finally realized he didn’t know where he was leading us and thus felt more terrible than before. I nearly suggested that we go back to save him the embarrassment of saying it himself. However, Father hadn’t stopped because he’d realized we had wandered off in the wrong direction, but because of a sudden crippling pain in his chest. He stood there gasping for breath and continuing to mutter what we thought were curses against Mother and her brothers. A few minutes later, he collapsed and died.

Father died that day and we came to the conclusion that Mother didn’t care about us. It was I who first reached this conclusion. “She hates us,” I said to Ziad.

“Who?”

“Who? Don’t you know?”

We swore not to forgive her. We actually decided, right there and then, to carry on with our Father’s resolve not to return home. We wanted to remain in that uninhabited area and deprive her of ever seeing us again. But we were still too young, and that very evening we went back home and remained with her until we reached the appropriate age to leave. We both left, one after the other, and never went back.

Over the years, whenever Ziad and I met, we rarely spoke of her. It was sort of an unacknowledged agreement between the two of us not to mention her unless absolutely necessary — for example, after she had fallen ill two years ago and had to move in with Uncle Rasem and his family in Beirut. She was too sick to remain living on her own, Ziad told me.

But now, when the news of her death has just reached me, I recall that June day in 1982, and I remember in particular the look of relief on her face the moment we were driven away. I remember that look, and I hope that it was a sign that her wish was fulfilled: the wish to go back to her youth, to the time before we came into her life, and back further to the time when she was a young girl, living with her family and spending all day in the company of her two brothers.

Well, Mother, I hope you’re happy wherever you are now! I, on the other hand, have never been happy; I have never loved anybody, not even my own brother, with whom I share the devastating memory of watching our father dying under the glaring sun of that summer day in that barren land. I’ve never loved anybody, Mother.