For their new theatre piece, Lebanese artists Lina Majdalanie and Rabih Mroueh invited contributions from three writers who cross borders of social class, gender, religion and geographical space. In a mix of theatrical performance, music and visual arts, these three voices bear witness to the courage of exiles, celebrating the metamorphoses of today’s Lebanon in a globalized world.

Nada Ghosn

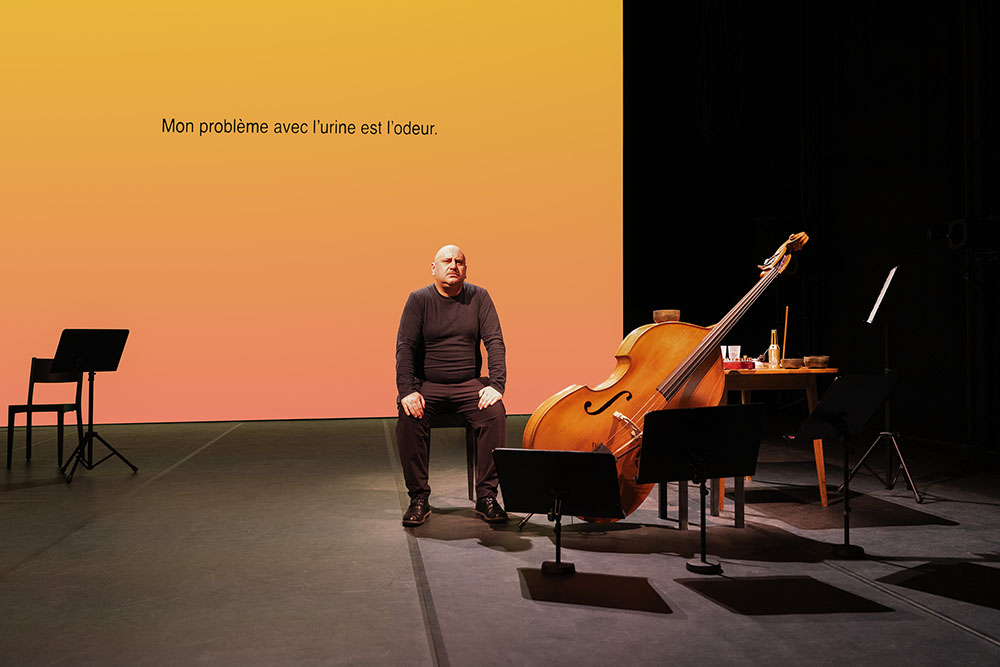

“One day in my early twenties, while stuck in one of Beirut’s usual traffic jams, I peed my pants. I found myself emptying the entire contents of my bladder on the seat. Since that day I have been afraid that the accident would repeat itself. And it did,” says actor Raed Yassin, declaiming Rana Issa’s text, “Incontinence.”

After receiving this first text, Rabih Mroueh and Lina Majdalanie, a couple who have been working together for over 20 years, decided to adapt it for the stage as part of Hartaqât (Heresies, in Arabic), performed at the Théâtre du Rond-Point des Champs-Elysées in Paris in September and now on tour across Europe.

Produced by the Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne, the performance, which blurs the boundaries between theatre, music and the visual arts, is divided into three chapters and three texts, by Rana Issa, Bilal Khbeiz and Souhaib Ayoub — Lebanese writers from three different generations who, like co-directors Mroueh and Majdalanie, were forced to cross borders in the middle of their lives, to go into exile far from their country of origin.

“We felt it was important to present these texts today, as they are linked to our Middle Eastern societies, as well as to the world. Just as we did, Rana Issa fled Lebanon because of the economic crisis, essayist Bilal Khbeiz because of his subversive writings and the decline in freedom of expression, and journalist Souhaib Ayoub — the only political refugee among us — because of his gay identity,” confides Mroueh in conversation with TMR.

Stories to deconstruct discourse

“Incontinence” is about the sensual, subversive pleasure of pissing on the world to better mark one’s territory — or perhaps to rid oneself of particular landmarks. The piece is a commentary on restrictive national borders, but also social restrictions on citizens. “Today, countries are closing their borders, and populist and nationalist rhetoric is gaining strength everywhere…States no longer have control over the global economy, and are becoming increasingly policed,” says Mroueh.

Through the story of her grandmother Izdihar, a Palestinian refugee in Lebanon, author Rana Issa rethinks the notions of Ummah (community, nation), Umm (mother) and Ummiyya (illiteracy). “Her text served as a catalyst for us, as it analyzes the relationship to language, linked to the mother, but also to the nation,” explains Mroueh. “Through the story of her grandmother, Rana Issa deconstructs macho and religious discourse, while showing that women can also be accomplices [to upholding those discourses].”

Should I of all people train myself to accept the authority of social conventions? What conventions could I trust in the wake of the end of the Lebanese civil war? How old was I when the war ended? Hardly a teenager. Like many of my generation, I didn’t find any reason to submit to any law or accepted rule of our violent society. Drugs were our emblem for rejecting authority, both familial and public. We used to chat about our psychological deviance as if depression and obsession were heroic qualities we aspired to. But of course, I didn’t share my bladder issues with my friends, nor did they share with me their own issues with the authority of shame. I didn’t follow the doctor’s orders. I was more interested in understanding the cause of my out-of-control bladder than finding a solution.

—from “Incontinence” by Rana Issa.

Personal stories trace interwoven struggles, becoming material for political, social, linguistic and queer reflection. How does one go on with one’s life when everything one has learned and built up through one’s experiences becomes a hindrance? What do you do when you’re born a second time, and find yourself a child in adulthood? Rana Issa, who wound up a refugee in Sweden, recounts how she found herself illiterate as an immigrant. For a long time, she had no command of the Swedish language, and came to find that her daughter had become her mother.

Exile, a second birth?

“We were looking for other texts and remembered this essay by Bilal Khbeiz, who was forced to leave Lebanon a few years ago when his writings put him in danger,” Mroueh continues. The journalist had to start a new life in middle age. Now based in the United States, his text attempts to reflect on what happened to him.

I watched my friends and enemies inherit from me. Some of them were eulogizing me. I was thankful for their loving eulogy but I could not return the affection.

That is how we die. Some types of death are not a choice but all types of birth are obligatory. You do not choose to be born but you may choose to die. Until now, after long years, I am unable to prove that I died of my own will but I was born twice.

When you become incapable in sharing love, that is when you are born again.

—Excerpt from “Non-functional Memories” by Bilal Khbeiz, translated by Rayya Badran.

Khbeiz recounts his defeat and disappointments not as a form of revenge-seeking, but rather of savoring defeat while continuing his political reflection on the contemporary world.

The socio-political roots of xenophobia

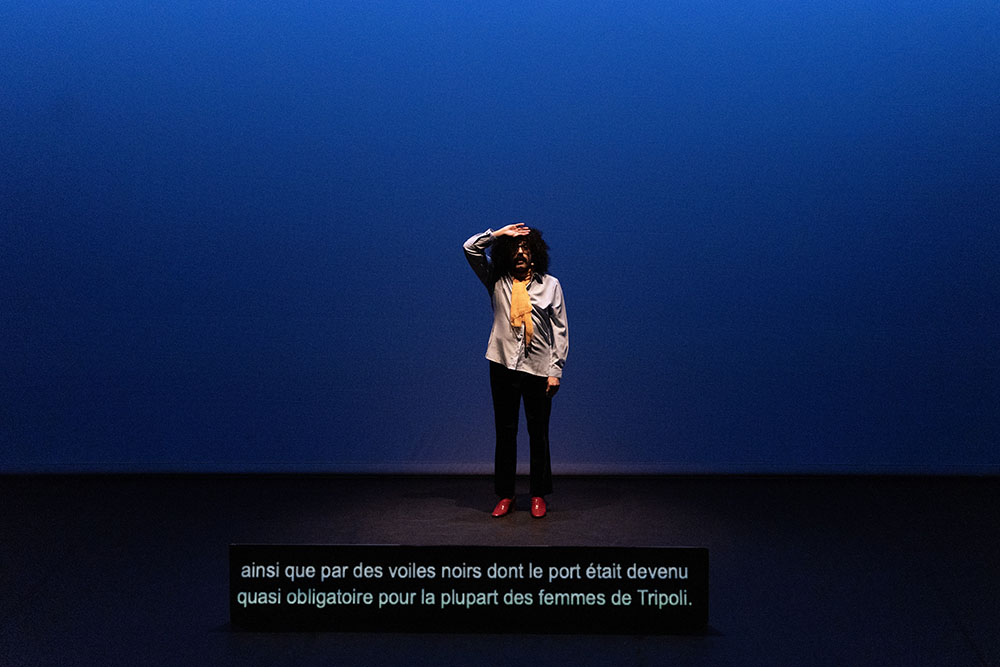

The director duo then commissioned a piece of writing from journalist Souhaib Ayoub, who had to flee his native Tripoli, Lebanon, as its increasing conservatism made life difficult for him as a gay man. His text breaks down stereotypes, showing another face to the city, which was once an open and modern cultural capital before a Salafist ideology took hold and flourished there during the civil war. More recently, Tripoli has been at the forefront of a revolutionary movement, becoming the de-facto capital of the Lebanese uprising that broke out on October 17, 2019.

For Ayoub, identities are intertwined with the urban, social and political forms that a city produces. The author calls himself one of the many images of Tripoli’s metamorphoses, where queer life emerges at night. To tell the story of his life and the early discovery of his homosexuality is to tell the story of his city. Denouncing the discrimination and threats he endured, testifying to his struggle for freedom right up to his exile, says a lot about life in the working-class neighborhoods like the one in which he grew up: the political conflicts between families, gangs and religious communities, and their economic impact. Through his story, Ayoub analyzes the social and political roots of these tensions, from the French mandate through the civil war to the present day.

My name is Gloria. My friends at school gave me this name: Gloria. I was 13 years old.

Gloria is a nickname for a trans woman from Al-Mina. I didn’t know what trans meant. Gloria was black and lived in a neighborhood that racists unashamedly call: negro neighborhood. It originally consisted of thatched huts built for African people whom the French army brought as “servants” for their soldiers. I inherited the nickname Gloria from an African trans woman whose grandparents were abandoned here by the colonizers, in a society which was not theirs and who became Tripolitans by chance, but of second or third or fourth rate. Exactly like my parents. (…) They lived their whole lives in Tripoli but remained foreigners in it. As for us kids, we remained the children of the farmer and the Syrian mother.

—Excerpt from “The Imperceptible Ooze of Life” by Souhaib Ayoub, translated by Rayya Badran.

Hartaqât, which already had its premiere at the Théâtre Vidy-Lausanne will return there after the series of performances at the Théâtre du Rond-Point des Champs-Elysées. “It’s vital to get these texts heard. The dictatorships of the world we come from mean that people flee disasters. Yet, as we’ve seen with the Syrian war, Europe doesn’t want to welcome these refugees,” remarks Rabih Mroueh. “There’s a crisis in political discourse. The left’s inability to be self-critical is strengthening the right. Religious discourse is on the rise because people have nothing left to hold on to. And this virus is present everywhere, even if you close the borders.”