This summer, the Tate Gallery’s seaside satellite, Tate St. Ives in Cornwall, opened a blockbuster exhibition straight out of Morocco, curated by Morad Montazami of the Tate Modern and Madeleine de Colnet for Zamân Books & Curating, in conjunction with the Tate St. Ives’ Director, Anne Barlow and the Sharjah Art Foundation.

Sophia Kazan Makhlouf

Why The Casablanca Art School at St. Ives? What could be the relevance of a Moroccan art college opened during Morocco’s French occupation, with its bright, ice-cream colors of the 1960s and 1970s, to visitors of the Cornwall Tate? Certainly on paper, the North African colonial outpost of Paris’ prestigious Ecole Des Beaux Arts is oddly juxtaposed with earlier work of the St. Ives’ Modernist community, by Patrick Heron, Roger Hilton, Peter Lanyon, Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, Bryan Winter, Wilhelmina Barns-Graham and Sir Terry Frost, which flourished from the 1930s and 1940s. And yet Barlow, who has been involved with numerous international and biennale exhibitions and awards, particularly Kaspars Podnieks and Krišs Salmanis’ 2013 Latvian Pavilion at Venice, with work tackling identity and representation, expresses to the viewer how both histories reject traditional modes of painting.

St. Ives and Casablanca’s brands of modernism explore exciting and fresh approaches to color and representation, based on the landscape and history. While the work of St. Ives artists delight in the brilliant, coastal light of the West Penwith, the cliffs and headlands, so Casablanca artists are inspired by the tribal Amazigh symbols and beliefs that predate the country’s occupation by the French and by its earlier Islamic occupation. These reflect the landscape and return to its deep-rooted African beliefs.

Artworks in the Casablanca Art School exhibition are many and varied. They include an array of paintings, ceramics, photographs of Amazigh tribal jewelry, as well as 1960s and 1970s film footage, architectural maquettes, woven textiles and printed posters, many of which come from the Tate’s own collection. Work from the estates of artists such as the artist and educator Farid Belkahia, director of the school from 1962 until 1974, Mohammed Chabâa and Mohamed Meleh, who joined the school as teachers in 1966 and 1964 respectively. Also included in the exhibition in an entire wall spread out with magazine covers and designs are examples of Abdelatiff Laâbi’s revolutionary cultural journal Souffles, to which many of the school’s artist contributed. The journal was banned in 1971 as a political “crimes of opinion” and Laâbi was imprisoned, but this challenge too seems to find its reflection in the art of St. Ives, which was a melting pot of defiance and socialist artistic beliefs, as artists escaping World War II and fascism in Europe sought solace in St. Ives, a town built on the fishing industry and on strong Methodist principles.

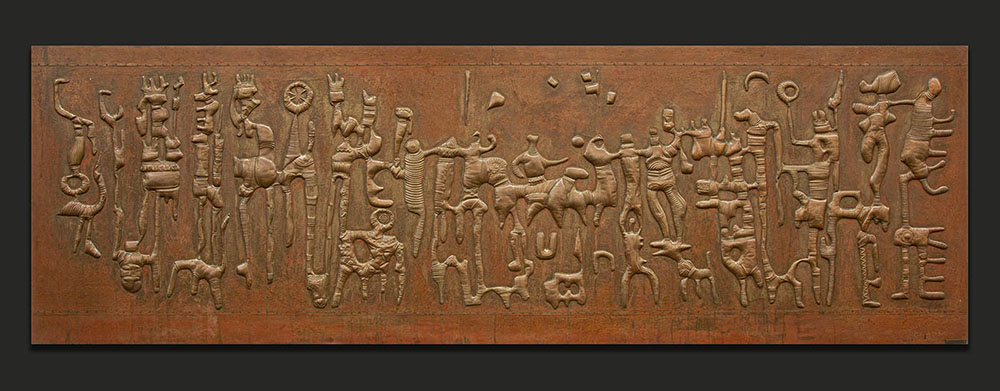

The exhibition in St. Ives focuses on Belkahia’s management and reformation of the school from the early 1960s onwards. Hailing from an affluent Moroccan family, Belkahia attended the Beaux Arts in Paris, not least because the Moroccan equivalent did not welcome Moroccan or female students to its classroom studios. Moroccan traditional art forms and crafts were seen as naïve and simplistic compared to the high art of the painting studio and Belkahia, who had been used to the liberated attitudes of Parisian student life and was also familiar with the holistic, Bauhaus consideration of art, architecture, craft and design as elements of a new, artistic visual culture, was determined to break with the past and supplant the school’s elitist and Western focus on art. During Belkahia’s time there, the Beaux-Arts widened its attendance by admitting Moroccans and female students and by embracing a post-colonial wave of civil awareness and regional empowerment in Morocco. With newly appointed teachers Toni Maraini and Mohammed Melehi, Belkahia held an outdoor exhibition entitled Présence Plastique, in Marrakesh’s most popular square, the Place Djema Al Fna. He hoped to bring contemporary art “back” to the people and into the center of Moroccan visual culture.

Belkahia saw the importance of teaching not only fine art but also anthropology and art history. He worked with the collector and anthropologist Bert Flint. Flint passionately traced tribal motifs and artifacts to their desert sources in the North and West African regions, travelling amongst the Amazigh, Tuareg and other tribes. Art was an intrinsic part of post-independence Moroccan culture and the Casablanca Art School ethos revolved around the creation of a new, unified Moroccan identity. As well as the 1969 Marrakesh exhibition, Belkahia prioritized artistic outreach in schools and in this way, he was also carving out a role for artists in society and in public life.

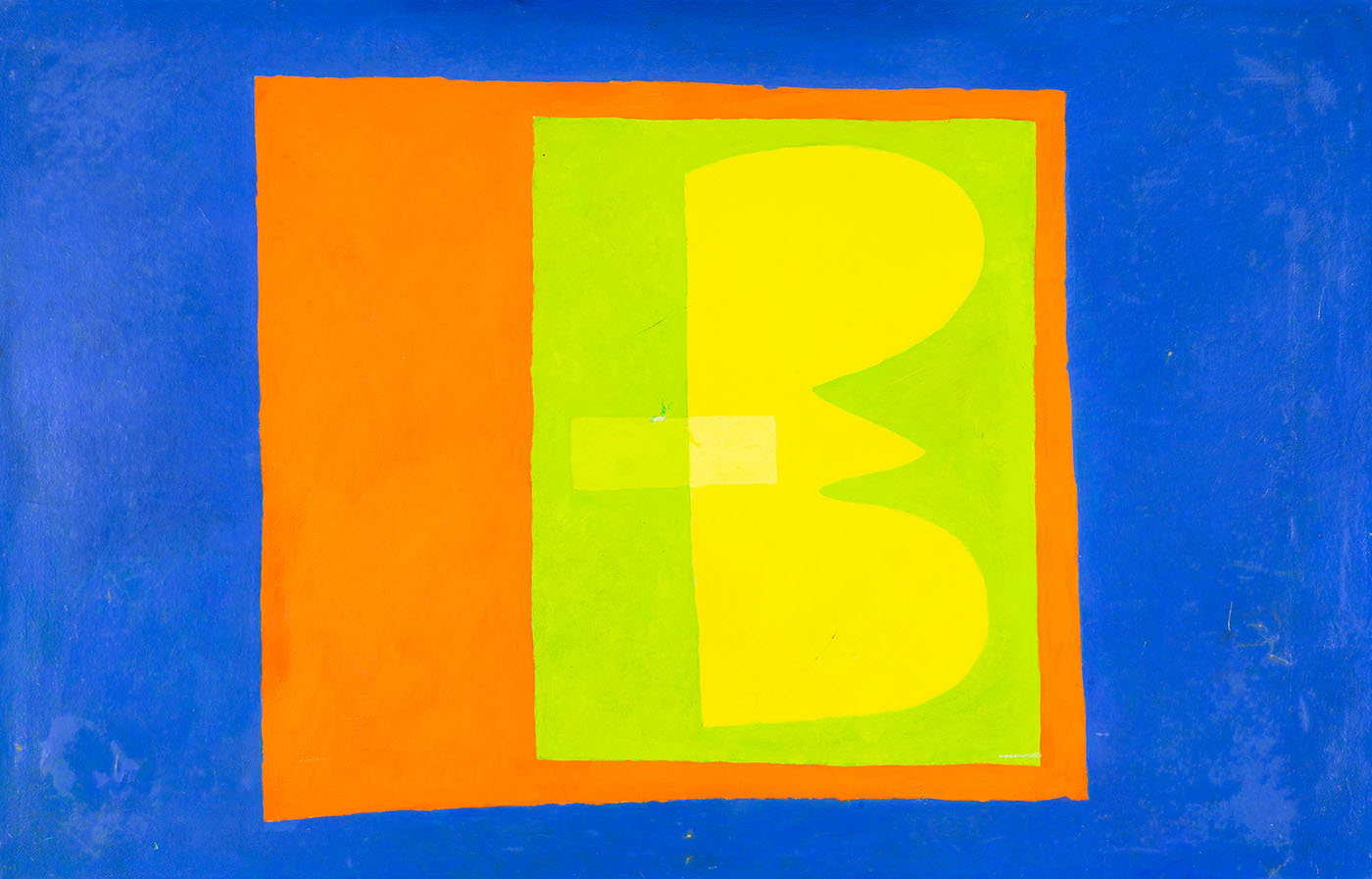

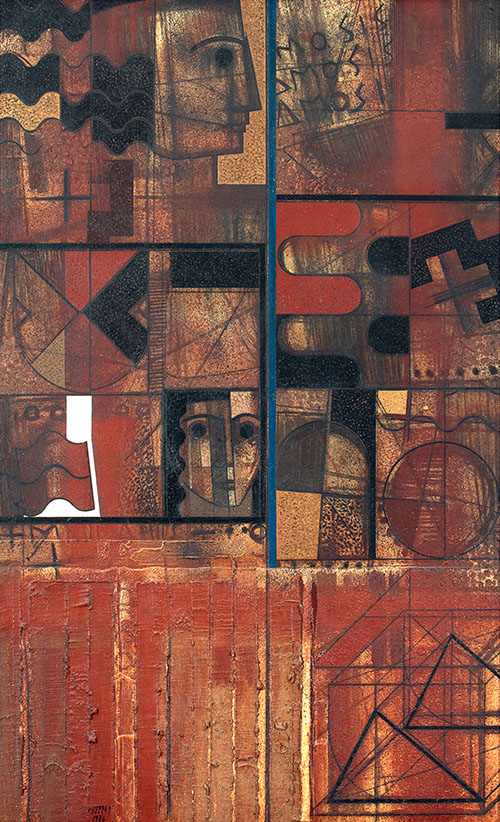

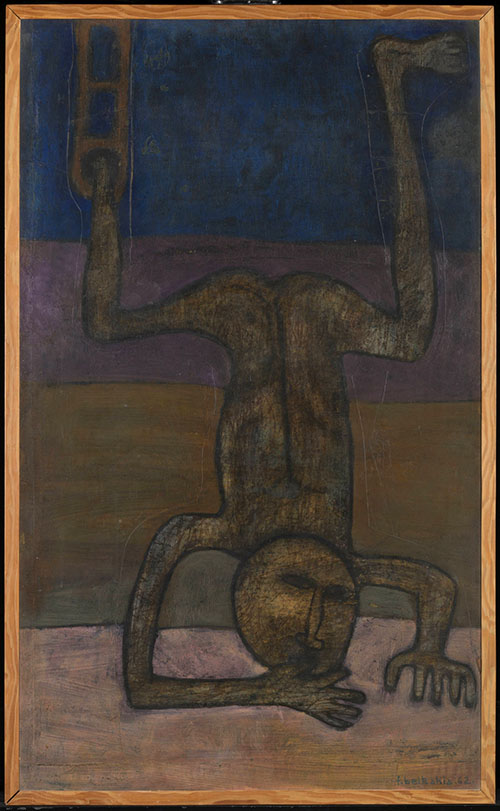

The convergence of art, graphic design, architecture, weaving and ceramics deviated from Western art models and the exhibition contains three of his own works. The haunting “Cuba Sí,” (1961) is painted in thickly applied oil paint on paper laid on plywood. It evokes Belkahia’s independent intentions and determination in the figure’s simplistic form, its pose and outstretched arms which express a satisfaction in its own sense of being. The title reflects the artist’s support of the Cuban resistance to American occupation during the Bay of Pigs crisis earlier that year. “Cuba Sí” uses earthy colors which are applied relatively roughly to evoke a basic and intentional application of form. It recalls some of the artist’s other works that are painted using indigenous pigments such as henna, saffron and sumac on untreated wood or animal skin canvases. Belkahia is situating a new and authentic brand of Moroccan art, materials and vocabulary of forms.

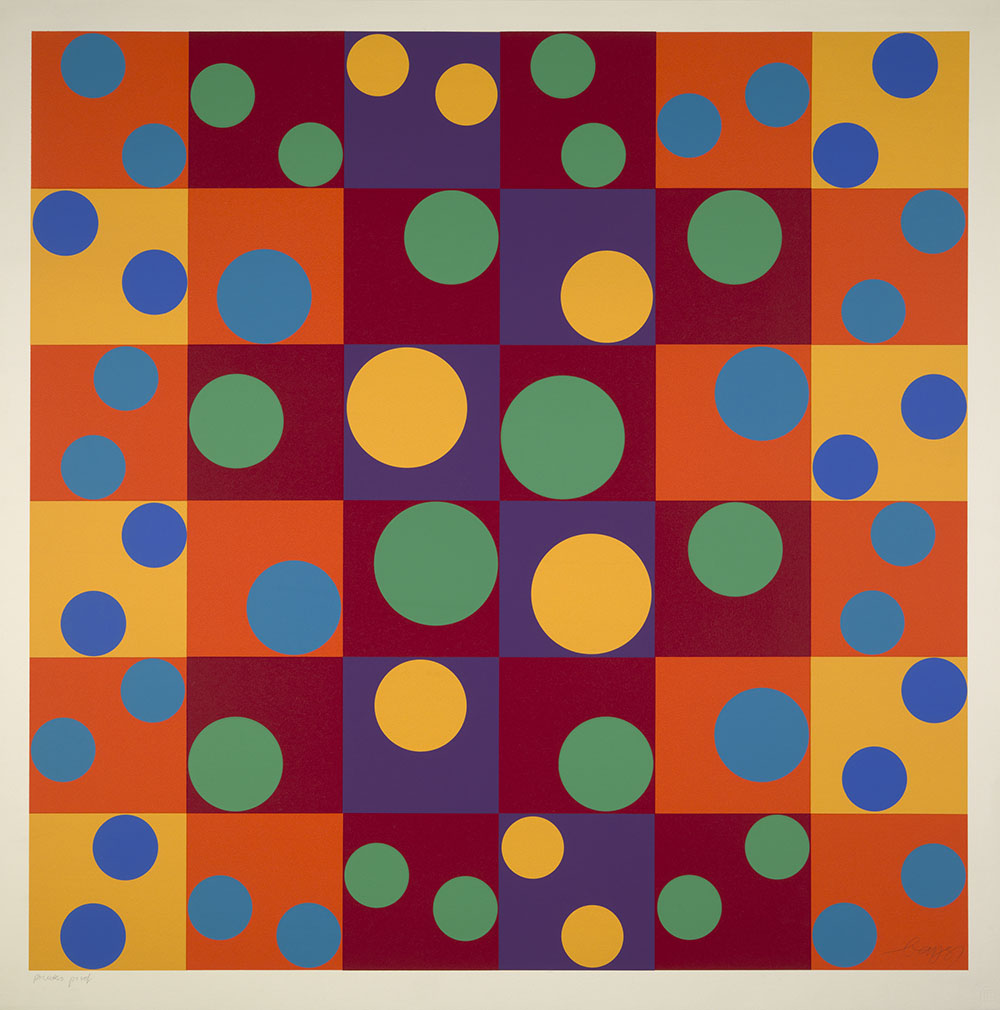

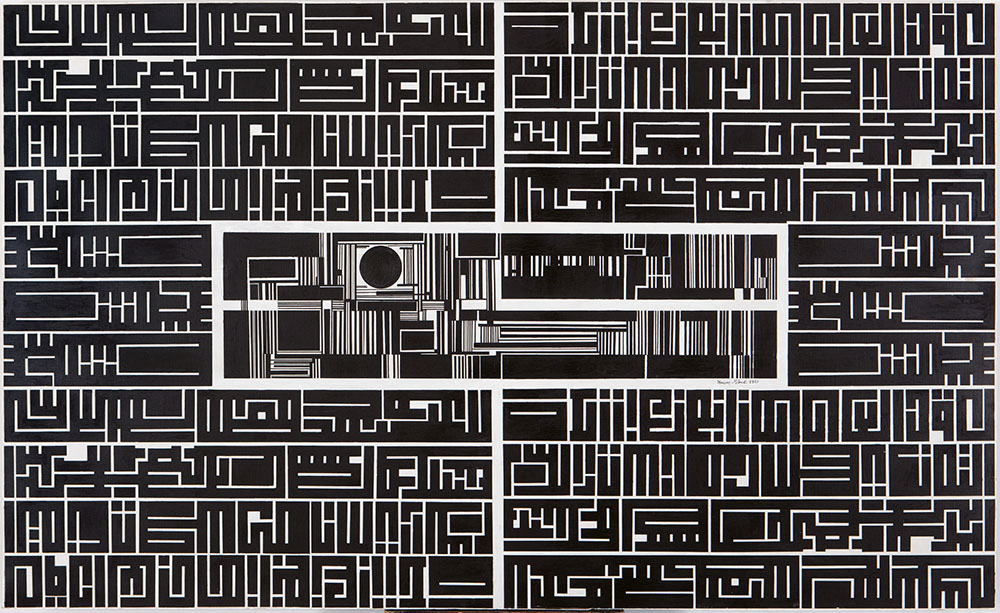

An entire section of the exhibition on the school’s Amazigh inspiration was supported by the research of Dutch linguist and collector Bert Flint. Geometric shapes, among them patterns of triangles, circles and rectangles can be identified in photographs of tribal jewelry, painted wooden columns and a thick Amazigh carpet, which evoke natural forms, animals and spiritual beliefs of the nomadic tribes of the West African region. These were taken up in the abstract paintings and art objects that line the gallery walls for the continuation of the exhibition. The attractive and traditional Amazigh shapes are taken by a wide variety of artist throughout the Arab world as the Casablanca Art School’s influence and its open message of inclusion and empowerment grew. Zoomorphic and prophylactic shapes from Tuareg imagery and wave patterns inherited from iconoclastic Islamic art gained a new lease of life in the abstract and graphic works of the Casablanca Art School artists.