Interviewed by Viola Shafik

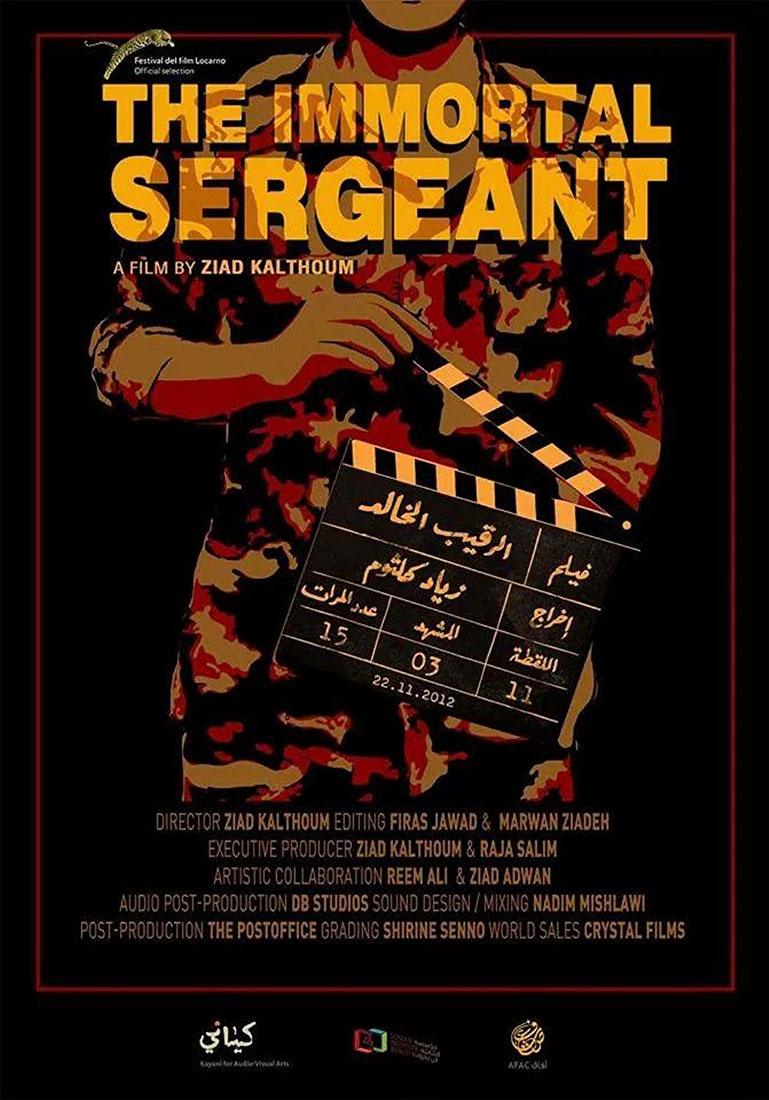

Ziad Kalthoum is an award-winning new generation filmmaker from Syria. He‘s made three creative documentaries, Oh My Heart (Aydal ayuha al-qalb, 2011), The Immortal Sergeant (al-raqib al-khalid, 2014) and Taste of Cement (ta`m al-asmant, 2017). While the first film was banned in Syria when it came out, portraying a Syrian Kurdish village, the second became a very personal account of the filmmaker’s experience in the army documenting at the same time the making-of The Ladder to Damascus (sulum illa Dimashq, 2011) by film veteran Mohamed Malas. Kalthoum‘s third film was conceived entirely in exile, a “magic realist” documentary on Syrian construction workers in Beirut. Presently, Kalthoum is working on a new documentary and has a fiction film project in development. He is based in Berlin but has gone from Homs to Beirut and Stalingrad, among other former cities of war.

Viola Shafik: In your upcoming fiction film project, Berlin features prominently. One sentence struck me in the proposal saying that for the main character Karim, a Syrian photographer, Berlin represented a cemetery. Why does he reconnect to life only when he leaves Berlin?

Ziad Kathoum: First of all, I did not choose Berlin; rather, Berlin chose me. I came to Berlin because I was looking for a sound designer for Taste of Cement. The first time in my life I traveled abroad I found myself in Stalingrad (Volgograd) in Russia, which was Berlin’s adversary in WWII. Most of the city was destroyed. Until now the traces of war are obvious and all of the city’s sculptures and monuments relate to war. When I returned to Syria and the war began, I went to Beirut — Beirut of course was ruined as well, and this while I myself hail from Homs, a city that has been in turn totally destroyed.

Coming from a war made me read Berlin differently. Many things raise questions here. For a young visitor from Spain or Italy, Berlin means Happyland, a place where he visits night clubs and enjoys music, drugs, whatever. This Happyland, or let’s say Alice in Wonderland is predestined to trigger a Syrian’s trauma. People come to Berlin to take drugs, to tour the clubs, have fun, lose themselves, wake up again, and so on. What about someone who comes from the war, to a city that has a lot to do with war? For instance, the messing-plated cement cubes you find on Berlin’s sidewalks, Stolpersteine, to stumble upon [in the memory of deported Jewish Berlin residents], they remind me of gravestones that carry a person’s name, date of birth and death. For a tourist, one of the first places to visit is the Holocaust Memorial (that speaks of the murdered Jews of Europe). It’s the biggest monument in the city and one of its main touristic sites. When I stood the first time between the huge cement blocks, they reminded me a lot of Syria after the collapse. Normally, in Syria you build a house and leave the concrete pillars on the roof for your son to fill in the walls. Quite symbolically, the son continues, leaves in turn new pillars for his son and so on. When the houses got destroyed, these pillars came down and turned Syria’s landscape into one of concrete mountains.

The Holocaust Memorial reminded me also that this country is still on of the biggest producers of weapons, exporting them to the world. What does it mean to know that Germany had sold chemical weapons to the Assad regime that he used against Syrians? How come, six million people were gassed in the Holocaust and this system is still producing chemical weapons? It shows also that we are living in a non-stop loop of war, moving from one war to the next.

VS: What does a space for an exiled person signify, a real space or rather a mirror that reflects his inner world? The latter seems to be the logic of your fiction film project.

ZK: In my fiction, Karim the photographer found himself in a position that he did not chose: he becomes a photographer for the regime. His task is to photograph detainees. After he finishes his job they are going die, and he becomes an accomplice in their murder. In Berlin, Karim is in pursuit of his own ghost, this soldier he used to be in Syria who stood behind the camera to photograph faces. He meets him at the Holocaust Memorial. Karim’s girlfriend or lover senses that he is about to collapse and takes him out to nature. This happened to me in reality. I found myself in Poland with a very strange family, people who use leeches for health reasons. When I tried them and saw the bad blood exiting my body, I imagined that the worm is eating up the bloody footage from my head, all these images of war in my memory.

Now I am also starting a new documentary film project. The idea for it developed around a year ago and by mere accident both protagonists are photographers. I thought about it a while and found it a good idea to make two films dealing with the meaning of the image and what kind of photographers we become in the moment of collapse. How is it to carry a camera that can become the tool for killing, as in the case of Karim in the fiction; the camera as revolver. As soon as he presses the button it is as if he has announced the death verdict for the person he photographs.

Thus, I consider it is a presentation from two different angles. The one who took pictures for the regime feels guilty, has a guilt complex. The second photographer, Muzaffar, is an old friend, who witnessed the uprising from the beginning. He has no guilt complex. He was not in any position responsible for the destruction or the killing etc. Yet he is in a state of loss, deprivation of place and people who left in front of his lenses, whose situation he documented. In fact, Muzaffar was one of the first photographers to document the revolution. Newspapers from all over the world published his photos. He escaped like many Syrians and found himself in Rouen, the capital of Normandy, surrounded by a wonderful landscape. Monet and the Impressionist school came from there.

Thus, I consider it is a presentation from two different angles. The one who took pictures for the regime feels guilty, has a guilt complex. The second photographer, Muzaffar, is an old friend, who witnessed the uprising from the beginning. He has no guilt complex. He was not in any position responsible for the destruction or the killing etc. Yet he is in a state of loss, deprivation of place and people who left in front of his lenses, whose situation he documented. In fact, Muzaffar was one of the first photographers to document the revolution. Newspapers from all over the world published his photos. He escaped like many Syrians and found himself in Rouen, the capital of Normandy, surrounded by a wonderful landscape. Monet and the Impressionist school came from there.

However, we discover that he lives in a place where the traces of WWII are still very much present, particularly in this area, where the Americans descended to liberate France from the Nazis: the tanks at the seaside, huge mass graves with thousands of deaths resulting from Americans and Nazis fighting at close quarters. When Muzaffar first arrived there, he isolated himself. Six years he spent behind the kitchen window photographing the landscape. He ended up with a huge production. Then, at one point he takes out his hard discs and starts printing his images from the war in Syria. This is the topic we are addressing, how a person in exile engulfed by such a wonderful landscape experiences the sudden reappearance of his trauma.

VS: If we ask Ziad, with whom of these two protagonists does he have more in common?

ZK: I was in the position of Karim. I was a soldier but I was not forced to take pictures of people who then proceeded to the guillotine. You saw me in The Immortal Sergeant. In the morning I was a soldier documenting the place that sparked the war, the evening I spent with Mohamed Malas running these interviews with people who came from the places on which the bombs had been dropped. In a way, I was here and there but not entirely. Documentation at the moment of collapse, the moment of destruction and war poses a big question, how are we documenting and from which perspective? Am I producing propaganda for a certain party or am I recording from my perspective without affiliation, religious or nationalist coloring? What does it mean to be a witness of the last portrayal of a face, like in Cesar’s case. If you remember, they have no expression. Cesar photographed 50,000 bodies with no expression. Karim is the opposite, he takes their last picture with their faces full of fear.

After he left Syria, Muzaffar asked himself many times, what am I shooting here after all the destruction that I recorded, this drama and tragedy? What to photograph now? I was reading even the images he took in Rouen as being different from anyone else’s landscape photographs. His breath, his soul, his subconscious are imprinting on his images. There is a continuity if you see his images from Syria and those from Rouen.

VS: I remember that your departure from Syria was quite dramatic. Had you finished your military service or did you desert?

ZK: Yes, I deserted. The main problem was that I “belong” to the Alawite sect, the sect that dominates the regime. Thus my crime was twofold, a double treason, as soldier and as an Alawite. This put me into a difficult position, with my male cousins. My relatives who do not share the same convictions accused me of betrayal, similar to my neighborhood friends from childhood. This double treason was difficult to deal with. Being a soldier who went to work from 7 am to 2 pm administrating the cinema building gave me space to maneuver, but the moment they put my name on the list and asked me to carry weapons, I evaded right away.

VS: You escaped to Beirut, right?

ZK: I remained for eight months in Syria. During that time I edited The Immortal Sergeant. I stayed in hiding in Damascus, then I was able to clandestinely leave to Beirut in early 2013.

VS: I can see indeed a graphic line going from The Immortal Sergeant in Damascus to Taste of Cement in Beirut ending in Berlin.

ZK: I discovered that later, while I was moving from one place to the other, which made me also understand my own characteristics as filmmaker. I am a person who makes films after he has lived in a place and has been affected by it. After making my observations, I develop a certain image of that place in which I was forced to take refuge. And to be honest, every place I escaped to carried a strong memory of war. Two and a half years in Beirut! What can we say about Beirut? Fifteen years of civil war, vast destruction that you can see until today and its aftereffects, be they physical on the buildings or on the faces of people, their behavior and how they deal with the situation. Then Berlin. Stalingrad, Homs, Beirut, Berlin, what an accident! Thus, by mere chance I was moving from one war place to the next. I fled the war and, naturally, could not prevent myself from seeing that city critically that everybody was admiring for its Alice in Wonderland character.

VS: As I know a different Berlin from my adolescence, I share your Alice in Wonderland impression and in how it spreads a big lie. What lies underneath, what you are expressing might be much more of the truth, in my view as well.

ZK: People get drugged, not just physically but also mentally, preventing them from putting any question marks. Even all the demonstrations that take place in Berlin, they surely have their justified reasons, but there is one very obvious thing that no one speaks about. We think we live in a place where free speech is allowed but in Berlin we don’t dare to speak about Palestine for instance.

VS: Yes, I was told that protests for the Palestinian cause currently are not authorized.

ZK: Here we come back to the same idea: In Syria it was like that and in Beirut you had an East and a West, the same mentality only different in style and power. This is why I also feel anger at that global regime. It thinks it has the right to enter any country, exchange a regime — as bad as this regime may be — and destroy the country for the sake of democracy.

VS: Can we turn to Ziad, the Syrian cinéaste before the war and after, or better, now in exile, as the war has not ended yet.

ZK I feel, I was the same before and after the revolution, but the drama intensified and me with it. The acts got bigger, the acts of killing took now place in front of us. When the revolution started and I was still a soldier, if someone was caught in the army carrying a mobile phone he was considered a traitor and executed immediately. I met this challenge when I went to shoot. There is my 45 minute-long documentary (Oh, My Heart) from before the war, shot in 2009. It was already challenging the regime as it tackled Kurdish society.

At that time, we were not permitted to bring a camera to the Kurdish territories. We were not allowed to shoot Kurds, thus as a cinéaste I was closing in with my camera on the red line. I was depicting a small Kurdish village populated by women alone. In Syrian Kurdish society men are absent for three reasons; either the fight on the Kurdish side against the Turks in the mountains, or they are wanted and detained by the Syrian regime, or they have escaped because of tribal revenge. What attracted me was how the women expressed their pain and suffering. When a woman tells her story, she stops suddenly and continues the story with an improvised song and lamentation.

Before the revolution, I dreamt of making films on the situation of people, also on their political situation, only that at one point everything exploded. Even the film on which I assisted, The Ladder to Damascus by Malas was a political film. (His lead actor, Ghassan al-Jabai, a theatre director just passed away.) He had been detained by the regime for twenty years. I imagine, even without the revolution we would be still making films opposed to the regime. I liked Omar Amiralay and worked with Mohamed Malas and Oussama Mohamed; all of them have been dissidents.

Also, I was brought up in a dissident atheist family. My friends and neighbors with whom I grew up became all “shabiha” [lit.: ghosts denoting the regime’s paramilitary terror squads] of the regime, instead. I cannot really blame them for the way they were brought up, what they learned, the brainwashing they underwent. If they had had the same opportunity as me, their situation might have been different. I can say Ziad remained the same, he did not leave the script or change, only that the scenery became worse, a criminal, corrupt regime whose detainees have been spending decades in prisons, a country that suppresses anyone who disagrees or says no to the regime and puts him in prison, a society where the regime tries to eliminate individuality, the peculiarity of each person.

At school we wore military uniforms. All of us had to shave our hair the same way, as in North Korea. We got deprived of our peculiarities to resemble everybody else. This had a strong impact on me and I was very aware of it quite early through my family and my upbringing.

VS: If you were to choose, would you continue to stay in Berlin?

ZK: I tried to learn the language but in fact I don’t want to stay. I want to complete the fiction and then leave. The minimum is to go to a sunny place.

This interview was edited and translated from Arabic by Viola Shafik and revised by Ziad Kalthoum.