Viola Shafik

Knowing that a good deal of Berlin’s imperial outlook had been trashed during World War II, the question that some people have continued to wonder in recent months, since the Humboldt Forum took shelter behind the fake Baroque façades of the reconstructed Berlin Palace, is whether and how this could inspire the public to take a closer look at Germany’s undigested colonial past. Particularly with the moving of the ethnographic collections from Dahlem to the new premises, paralleling Berlin Global — an exhibition dedicated to the city, that tackles among others revolution (!) — the question became, was it was possible to unmask that resurrected colonial bastion through critical or even revolutionary comments and artistic contributions? Or rather, did we need to contend that the bastion once again was reproducing its cultured mask by a continued insistence on the unsolicited storing and “rescuing” of other people’s arts?

Of course, this may not be an either/or question. Instead, I choose to share my contemplations in a trifold manner, projecting them onto three different canvases — a film, a painting and a museum — to create a triptych, so to speak. This should also help me portray a city in which I’ve been based for two decades, a city that I came to know and have visited numerous times since my adolescence. I remember it still as a wounded city, a damaged, inconsistent cityscape, shrapnel piercing its walls, with gaping ravines in its streets, and gaps or holes where buildings used to be hastily reconfigured into makeshift playgrounds. My birth year was the year when the first barbed wire and concrete walls started blocking the East from the West.

For decades, the divided city remained an island, and a place for alternative or even revolutionary culture. I got my first Super 8 film screened in the late 1980s, in an underground film festival in one of Berlin’s famous squatter houses. Later this place became the Eiszeit Movie Theatre. It no longer exists. The city was a magnet. It attracted me like many other young adults born into West Germany’s economic wonder, who were sensing the tenacious Fascist undercurrents of which I was even more afraid, due to my mixed, German Egyptian background.

I was too young to have taken part in Berlin’s famous student movement and to have shared life in the radicalized communes that found their safe haven in Berlin. My awareness had grown only so much to know that a policeman gunned down the student Benno Ohnesorg during the 1967 anti-Shah demonstrations, and that the movement was spearheaded by Rudi Dutschke, whom German Neo-Nazis conspired to assassinate in Berlin in 1968. He not only described the Vietnam War as a colonial war but dreamt too explicitly of establishing a more egalitarian society. To this movement and to the subsequent events, but also to the preceding famous Eichmann Trial, we owe that the dissection of German Fascism and its horrific repercussions became part of our school curriculum. Hence, we were taught, or, thought: German nationalism?! Holocaust?! Never again!

In fact, in West Germany we were trained to critique the nationalist excess through the lens of antisemitism, not though with a critique of capitalism, colonialism or even racism. We did not study that the extermination of the European Jews had been preceded by the Herero and Nama genocide in Namibia, for example, and the extermination of other indigenous people in the Pacific. I knew from school only that Germany had owned a few negligible (!) colonies, such as Togo, Rwanda and some west Pacific islands, but that these had produced concentration camps and genocide? No!

The extermination war against Namibia’s Hereros and Namas took place shortly before WWI, from 1904 to 1908. It leaked into public awareness only in 2002, with official Namibian demands for restitution. My first time to see and learn about the events in their full gravity was actually in the cadre of a Berlin exhibition in 2017. This lagging behind may explain the crucial shortcomings of the current debate around the colonies’ plundered treasures.

The film

In 2002, I was doing research in Berlin for my documentary Journey of a Queen (Arte TV, 2003), tracing the acquisition of a small ancient Egyptian wooden bust representing Queen Teyi, Nefertiti’s mother-in-law and Akhenaten’s mother. The head was kept in the “Marstall,” previously the stables of Charlottenburg Palace. After WWII this place had become home to West Berlin’s Ancient Egyptian collection. During the war most of it (but not all!) had to be moved from its original place, the Neues Museum (New Museum) to different hiding places.

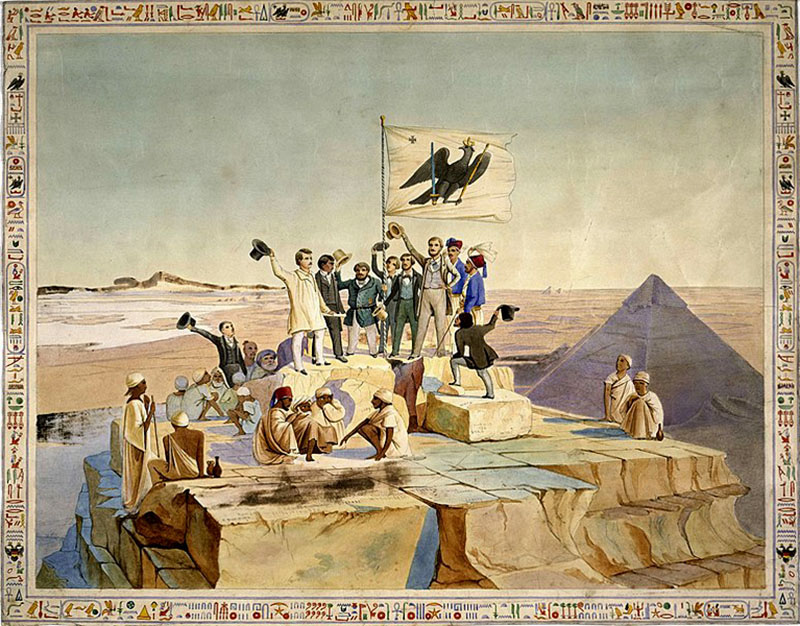

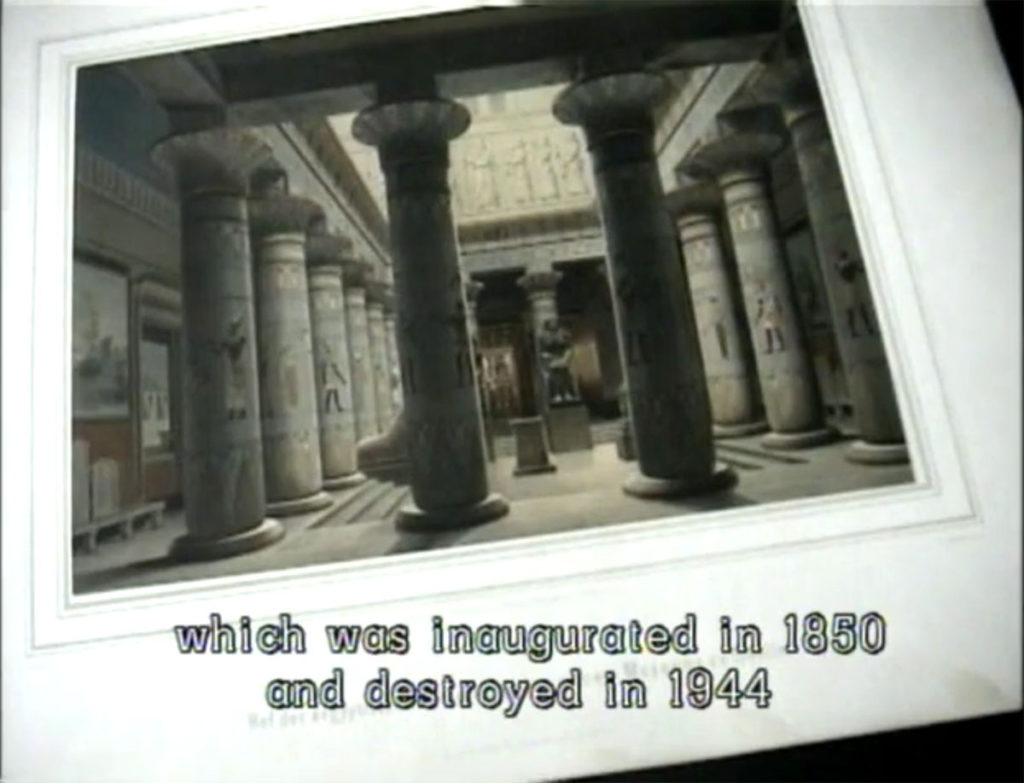

The Neues Museum, bombed to rubble in 1944, carried this name because it was more recent than the Pergamon and the Bode Museum. In 1855, it opened its doors to specifically display Berlin’s growing Ancient Egyptian collection. Like London and Paris, the Prussian capital and since 1871 also seat of the German Kaiser or Emperor was competing for colonies and treasures. They put on display their most splendid collections in huge monumental constructions, meant to promote the respective colonial powers and their rulers. The Neues Museum lauded and mirrored Ancient Egyptian monuments with its interiors shaped exactly like an Egyptian temple.

Kaiser Wilhelm II (ruled 1888-1918), whose country had missed out on extensive colonies — or so the elites thought — was eager at least to compete through technology in cooperating on the Berlin-Baghdad railway and through archeological excavations in Palestine and Egypt. In his endeavors, the emperor was assisted financially by a group of Jewish businessmen, among whom one of the best known was James Simon, whose wealth stemmed from cotton fabrication. He financed antique acquisitions or even entire archeological expeditions, like the one which brought the iconic bust of Nefertiti to Berlin.

I started getting familiar with these details because in 2002 — at a time when the Egyptian queen was still emblematic for Berlin with her face advertised everywhere on posters across the city, while the head of the Egyptian antiquity administration, Zahi Hawwas, was loudly demanding her return — I began what they would call today a provenance study, researching the trajectory of another likewise royal sculpture on display in Berlin. The wooden bust of Queen Tiye that I chose for the film represents in fact Akhenaten’s mother and Nefertiti’s mother-in-law. It is a tiny object that still is mind-blowing in its grandeur and finesse. One of its peculiarities are the elaborate earrings that come forth beneath the braided hair-dress. The sculpture had attracted my attention already in 1997 at the Metropolitan Museum New York, in a show dedicated to the royal women of the Amarna period.

What triggered my research was the fact that the sculpture had changed over time. In 1997, it appeared decorated with a royal feather crown that was missing before. Moreover, the museum boasted with computer x-rays that showed that the original hairdo had been covered and altered most probably at the time when the Amun priests had returned to power and Akhenaten’s mother returned from Amarna to Thebes (Luxor). Interviewing the museum’s director and an opposed critical Egyptologist, I found that the feather crown was actually a controversial matter: it was a coup good for promotion but the museum’s restaurateurs had no hand in it. The feather crown had been found accidentally in the museum’s storage rooms and the director considered it a match for the sculpture.

Diving deeper into the matter, I made some disturbing discoveries. Ludwig Borchardt, an architect turned archeologist who had also brought Nefertiti to Berlin, acquired Tiye from an antiquity dealer on behalf of James Simon. At the same time he claimed that the head was found in a “Kohlekeller” (coal cellar), typical for Berlin where coal served for heating in wintertime but it is definitely nothing we know from Egypt and Fayum, where the item supposedly came from. In James Simon’s house, the bust was standing around for something like two decades and was on one occasion dropped by a visitor of the house. But this was not the only hazard. Before delivery, Borchardt had scratched off parts of the hairdo and made visible one of the earrings. He also drilled a small hole in the backside of the head to see what’s beneath. I had not expected this to be the trajectory of the piece, and I have to admit, it shook for the first time my firm belief that the

West represented the better home for the artefacts of the “underdeveloped” global South.

All in all, the story of the queen’s journey felt like a story of displacement. I chose to start the film with a song. I asked the wonderful Ukrainian singer Ludmila Krupska, who had left her homeland to offer her children a better future, to perform a nostalgic song in the Berlin subway, as we see so many musicians still do today to make a living. At the same time, I tried to give the sculpture a voice by reciting words from the Book of the Dead on her behalf. For I knew that Ancient Egyptian pictures and sculptures were not designed as realistic representations, but rather as magic objects which were believed to expert power, just like a spoken spell would do.

The museum

In my film I made it also clear that the museum’s role had changed over time, from imperial status symbol towards a subsidized mercantile enterprise, to be promoted by spectacular acts and findings. And the story went on, of course. In 2009, Queen Tiye had to leave its home again when the entire Ancient Egyptian collection moved back to the meanwhile restored Neues Museum. Understandably, the latter’s restoration did not create the same fuss as did the Berlin Palace, which in part dates back to the 15th century. Bombed during the war, the GDR decided on its total demolishing in 1950 and erected on its site the Palace of the Republic. The latter, with its all glassed modernist construction, advanced into an important showpiece of socialist GDR architecture. After unification in 1990, this in turn was torn down which made the decision to rebuild the royal palace seem to carry a quite conservative note, or so it seemed to me.

Another important matter that increasingly inflamed the tempers was the question of provenance and restitution with regards to the treasures kept at the Humboldt Forum and meant to be displayed in the palace. These matters had still not made it to the surface when my film came out in 2003. Plus, for the case I chose the connection to colonial plunder did not seem as overt, as for example in the case of the giant boat from Luf Island (Papua New Guinea), so meticulously investigated by Götz Aly, the German historian and journalist. When the boat was taken away, not enough native islanders had survived Germany’s so-called punitive expeditions (Strafexpedition) to navigate it. Another prominent example was the robbery of the royal Benin bronzes, whose details were made public by the French historian Bénédicte Savoy. These showpieces of the Berlin collection had actually been looted by British troops in 1897 after setting the royal Oba palace in Benin (Nigeria) on fire and scattered around Western capitals.

According to historian Savoy, the Stiftung Preussischer Kulturbesitz which runs the Humboldt Forum showed little capability in addressing these questions. Being a member of the Forum’s expert committee, she resigned in 2017, attesting to the Stiftung’s “total sclerosis.” She also compared the planned Palace museum to Tchernobyl, an ill-fated reactor clocked in concrete. Luckily, her protest was not in vain: Germany agreed to return the bronzes to Nigeria — or at least declare them Nigerian property (as of this writing, only two pieces of some one thousand have been returned). Also, the Forum established four positions for provenance studies.

Notwithstanding, a walk through the “ethnological” exhibition after the museum’s opening in 2021 had not lost the character of an “imperial trophy collection” (Götz Aly). My impression, too, was that despite or precisely because of the information provided on German military actions and intrusion, the collection emanated an overwhelming sense of violence and displacement, plus a general lack of precise information about the use and cultural or cultic context. The obvious loss of dignity these objects suffered because of that was shocking.

The painting

One floor beneath the African and Micronesian collection, the Humboldt Forum chose to present the interactive Berlin Global exhibition that starts right at its entry with a section on revolution. I am not sure why this specific topic was chosen to represent Berlin. A malicious guess could be the whitewashing of the disappearance of the Palace of the Republic? Or a laudatory gesture to Germany’s unification in 1990, commonly referred to as peaceful revolution. For someone who has experienced the 2011 Egyptian uprising, this notion may seem unconventional, but in the end, notions are always debatable. Be it as it is, Egyptian fine artist Hanaa El-Degham, a good friend, was asked to contribute an art work to this exhibition. During the Egyptian protests she had made a name for herself as a muralist, and so she was expected to contribute something along these lines. Giving her consent to participate, however, in the cadre of the general controversy surrounding the Humboldt Forum was not an easy decision.

When she finally agreed, Hanaa was criticized by those who opposed the Forum. I remained hesitant. As certain as I was of my friend’s motivation to hold on to the concept of revolution and to express her uneasiness with the Forum’s colonial treasury, I knew in theory how difficult, if not impossible such an enterprise could be. Marching through the institutions had already been written on the banners of Rudi Dutschke’s movement and its sympathizing revolutionary artists. Hadn’t their messages been so easily absorbed by consumer culture and the arts market, with blatant criticism and anti-bourgeois sentiment becoming almost compulsory for good sales, as art historian Walter Grasskamp has so poignantly described in his book Der lange Marsch durch die Illusionen (The Long March Through the Illusions)?

Against all odds, my friend came up with a great idea: she invited scores of people, colleagues and friends, to scribble or draw on the canvas. A huge variety of concerns came together, from global injustice to the question of Palestine, displacement, migration, the refugee crisis, up to racism and white supremacy. As for my contribution, my first thought was to discuss Gilles Deleuze’s warning of institutionalized revolution in coining instead a concept of revolution as something eternally in the making — devenir-révolutionnaire/becoming-revolutionary. And indeed, Hanaa allowed me to design a stencil like the ones which had filled the streets of Cairo during the uprising, using the spiritual sign of the serpent that bites its own tail with Deleuze’s sentence on top.

With this sort of self-created found material at hands Hanaa’s mural/painting The Renaissance of Osiris started to take shape. In the process, she developed a collage composed of her own visual repertory and that of others. Drawing from her personal memories, from her studies of Ancient Egyptian arts, Islamic architecture, up to the visual repertory of Berlin and its history, the WWII refugees, East European migration, rubber boats in the Mediterranean, and the like, she started to develop a huge fragmented mural. As for the stencil, I was later surprised to see that she had re-interpreted it as a throne for seating the God Osiris, the deity of resurrection and renewal. In fact, the whole painting was designed like a movement of resurrection. Slowly leaving the above described static cabinet of horrors on the left side of the canvas the depiction moves toward a more dynamic final moment on the right side: three somersaulting boys give way to a little girl (akin to an alter ego of the artist) is seen swinging an ancient map of the Nile Valley on a boat-like swing typical for Egyptian Saint Feasts, thus swinging slowly but surely towards the borders of the canvas.

Jump, little one! Jump out of the frame, out of the museum…! Or maybe not! That moment of the girl’s lingering, being ready but not having broken free yet, in that I find, Hanaa has succeeded, or so my projection at least, in expressing regardless the confinements of an old powerful institution marked by centuries of warfare and exploitation and hostile to any revolutionary change a state of “becoming-revolutionary.”