The Baghdad native became a Middle East correspondent after working with the Guardian as a translator and fixer, and has covered the region for 20 years.

A Stranger in Your Own City, by Ghaith Abdul-Ahad

Penguin 2023

ISBN 9780593536889

Iason Athanasiadis

Apparently, Ghaith Abdul-Ahad is invisible.

For 20 years since the US invaded Iraq, this little-known, much-awarded Iraqi journalist has consistently covered war in the region, featuring breath-stopping forays into the Syrian civil war. Turning the final page of A Stranger in Your Own City, I am left wondering how Abdul-Ahad, also a reporting veteran of Yemen’s civil conflict, manages to remain so below the radar, both while traversing lawless landscapes, but also after so many years of addressing western news-consuming publics.

Before the post-9/11 wave of wars, uprisings and instability accelerated the Middle East’s devastation, its cultural exoticism exerted a spellbinding fascination on the West. But even as the region was an object of intense observation, its interpreters in the western media usually lacked fluency in its main languages, and got by with translators and fixers. While the reverse would have been unacceptable for an Arab journalist dispatched to cover Washington DC or London, in this case the double standard passed unremarked, despite often producing reporting howlers, like characterizing the Arab Spring as a social media-fueled, pro-civil rights movement led by western-educated liberals.

With fluency in English spreading, our interpreters of the region transitioned from western area specialists to a new cadre of culturally better-equipped locals. Βut unlike renowned correspondents such as George Polk, Robert Fisk, or John Simpson, they struggled to achieve recognizability even as their work featured in mainstream western media.

Reporters like Ghaith Abdul-Ahad, Rania Abouzeid and Nabih Bulos produce direct, unmediated, and much-awarded journalism. They should be media stars, or at least people listened to deferentially. Instead, their names hardly raise recognition among average informed news consumers. While reading Abdul-Ahad’s book, I often thought of Abouzeid’s No Turning Back, or Nir Rosen’s In the Belly of the Green Bird, both classics about the Syrian civil war and the Iraq insurgency that didn’t reap the widespread attention they merited.

A chronicle of pulped cities

Abdul-Ahad grew up in Baghdad during the Iran-Iraq war, studied architecture, and did “ugly jobs for ugly people who had the money to afford ugly houses.” A few days after Iraq’s occupation, a chance meeting with a British reporter while touring Saddam’s abandoned palace, launched him into journalism. His two decades of covering war in Iraq and Syria led to multiple media awards and now a book, summarizing in 400 pages the conflicts in Iraq and Syria better than millions of words and minutes of western media time.

A Stranger in Your Own City drags us through initially dysfunctional, then disinterred, and finally pulped cities, in a compilation of collapse and civil war. Born in one of history’s most significant cities, Abdul-Ahad becomes our guide during one of its worst periods, as violence and sectarian cleansing scar the once-mighty capital.

Like many war correspondents, he starts his book with a journalistic cliché, inside the room of one of those wartime hotels that become iconic through conflict by virtue of the foreign press pack choosing them. To Beirut’s Commodore and Sarajevo’s Holiday Inn are added Baghdad’s Palestine Hotel and subsequently the Hamra Hotel, where journalists relocated after the former was repeatedly targeted.

But there is a kick to the cliché: The Hamra is familiar to Abdul-Ahad; he used to frequent it as a child. Once “a fashionable enterprise with the sharp, concrete corners of brutalist architecture, chic seventies furniture and an excellent bakery,” the Hamra is long past its glory days by the time he returns as a journalist.

Tossing and turning on a narrow bed in a room “heavy with the dust of two decades of war, sanctions and occupation,” Abdul-Ahad reminisces that “a long life ago, I swam here every summer.” The sounds of a city at war percolate through the windows, “the distant thud of mortars crashing in the Green Zone, the monotonous din of supply convoys, shrouded in the safety of the dark curfew hours.”

So A Stranger in Your Own City adds memories to the war memoir, as Abdul-Ahad wanders through a formerly familiar city replete with reminiscences. But there is a twist to the twist: war and journalism give him the opportunity to transcend his comfortable background as the product of a family comfortably employed in the public sector, peeling away all the social and geographical layers erected by his class — even as he is in the process of losing himself in a 2003 Baghdad that is a blank background against which Iraqis redefine their identities. As Abdul-Ahad walks the disintegrating city, his formerly prestigious professional-class childhood friends are suddenly “useless … in a Baghdad torn by civil war.” Soon they have emigrated, and he realizes he is reborn, amid the obliterated landmarks of his life, as “a stranger in my own city.”

One such landmark is a “small and filthy café with two or three metal tables and rusting stools.” It used to be an oasis when the city was poor and himself hard-up, but now its “metal shutters were twisted and riddled with bullets. The cafés had closed long ago, and their wooden benches piled on top of each other like the dead bodies that littered the city.”

Another day, he tracks down his old schoolmate, Hassan, sitting in a once-elegant, now old and worn living room, thick with the dust of decades of neglect. But the meeting is anticlimactic. “He was bewildered at the return of a ghost from two decades ago… How dare I come from a distant past to trouble the monotony of the present?” Abdul-Ahad writes. Rather than disappear through emigration, he decides to adapt to the new reality.

Liberation, then collapse

By the time it was Iraq’s turn to be liberated, Abdul-Ahad was six months in arrears on rent for his small room. When US troops rolled into his neighborhood, he emerged to watch a scene seemingly out of a Hollywood film. First contact was with a western photojournalist who gingerly approached him with a telephoto lens, as if trophy-shooting rare wildlife.

Abdul-Ahad’s stint as a translator for the Guardian evolved into an apprenticeship in his largely-unfamiliar country, even as new, terrifying visages crowded out its former self.

“Baghdad was no longer my city; it did not matter that I had lived there for three decades,” he writes. “I obtained several fake ID cards, with different tribal and family names on each to be used in different parts of the city.”

Soon he was criss-crossing invisible borders to converse with the phantoms of western nightmares — insurgents, jihadis and members of the security services — and being published in the Guardian. His social intimacy permitted him to roam through what became two of the world’s most lethal countries, and witness some of the contemporary Middle East’s most defining events: the suicide bombings in Karbala during the first public Ashura celebrations in decades; the battle for Fallujah; rebel-run Aleppo; and the battles for Ramadi and Mosul. But more fascinating than his presence at the famous set-pieces is the significance of the unknown places and moments he highlights: the wastelands of death produced by the civil war; the mosaic of international jihadi brigades coalescing in Iraq and Syria; and the youth-led Uhud uprising against corruption.

On the threshold of the 21st century, Abdul-Ahad embodied a new type of local foreign correspondent; no longer the outsider parachuting in to do a few stories and move on, but a local forcibly dislocated from the country he grew up in. What’s more, he illustrates his work through eloquent architectural sketches and photography.

Collage of urban collapse

Amid looted hospitals, schools burned or occupied by squatters, and failing public services, Baghdadis fearfully realize that “their new colonial masters had no clue, had done no planning and made no preparations for what was going to happen after they invaded the country.” And when the myth of an American-generated prosperity clashed with the occupation’s realities, chaos and destruction followed. Baghdad shifted from its euphoric April 2003 incarnation into a place of “frustration and then fury.”

And yet another Baghdad was growing in parallel to the chaotic streets, as the Americans converted Saddam’s palaces into office space and staffed their administration with “young, naive zealots who … represented the worst combination of colonial hubris, toxic racist arrogance and criminal incompetence. Many would later write books about their heroic struggle in the lands of the Arabs.”

In fact, Abdul-Ahad had little access to this firmly insulated world, evocatively documented in Rajiv Chandrasekaran’s Imperial Life in the Emerald City.

Civil war spread beyond the Green Zone. Residential districts became theatres of score-settling, before progressing to sectarian self-cleansing and physical division through fences, concrete walls and sand berms. There was also the Sadda, a no-man’s land fertilized with blood after it got designated the place for trouble-free executions and body-dumping.

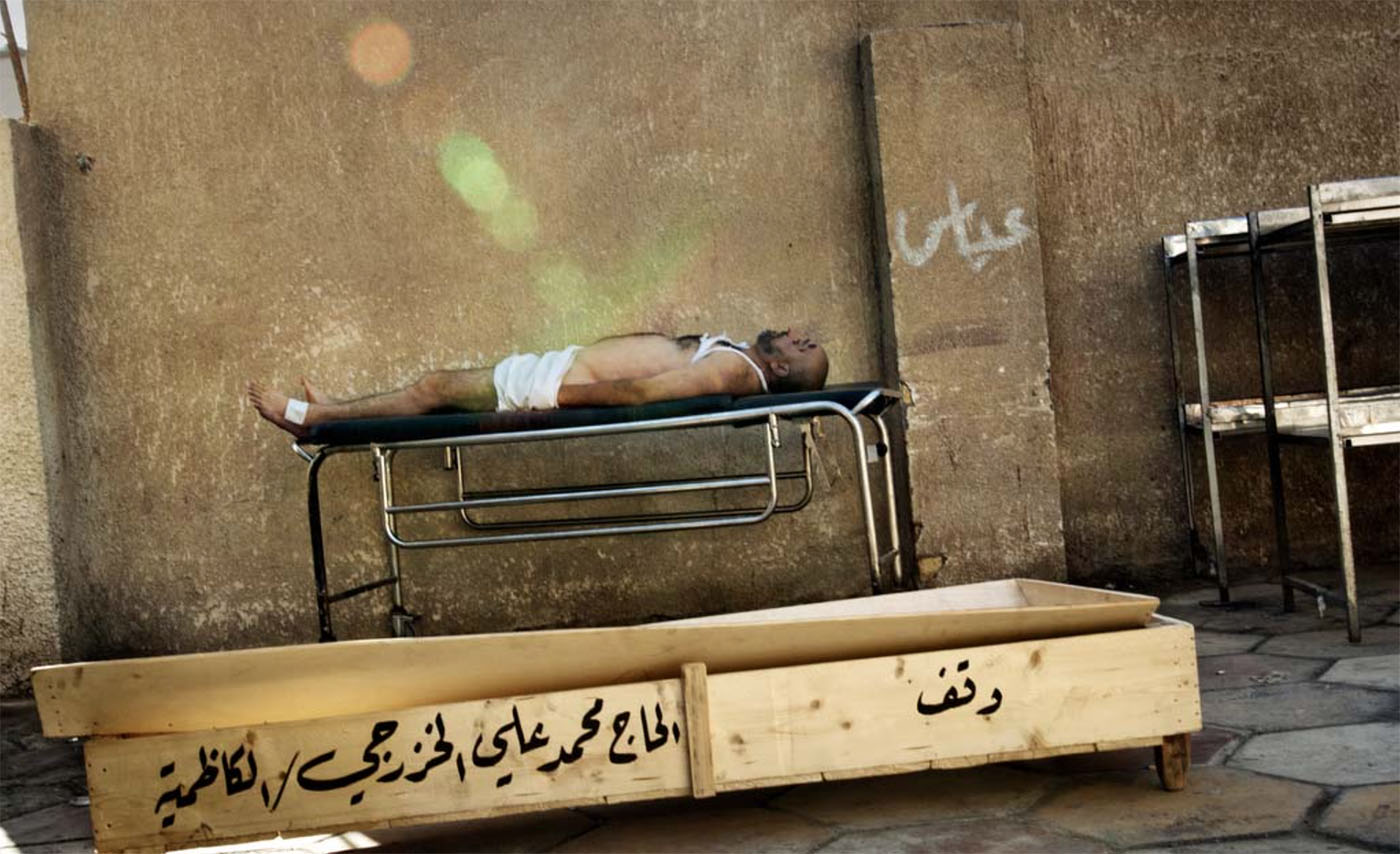

Victims of nightly killings increased to the point where morgue officials improvised a “hellish slideshow” composed of photographs of the dead over which family members pored, searching for their missing relatives. Death became so recurring that many of the book’s characters bow out abruptly, closing their own chapters. One of them is Hameed, a militia commander whose open mindedness clashes with the Zeitgeist and whose epitaph is notepad-epigrammatic: “Taken by Shia militias? Sunni jihadis? His body was never found.”

Land of no hope

Abdul-Ahad takes us into spare, electricity-less rooms where psychiatrists, intelligence officers and jihadis reveal “a version of events I was not supposed to witness.” One day, arriving at an ambush of an IED targeting US soldiers, he witnesses American helicopters shooting into a crowd of civilians; afterwards he reads a military statement reinterpreting the vindictive counter-killings as a targeting of the damaged Humvee to avoid it falling into insurgent hands. Later, Abdul-Ahad moves to live in Istanbul, whose “green and noisy places” remind him of a no-longer extant childhood Baghdad. He also discovers that a large part of the Arab world has relocated there, to conduct covert dealings.

“You can form a militia in Yemen or Syria, Libya, Sudan right now, while sitting in Istanbul,” he informs me during a conversation. “But once you form it and pump weapons into the streets, try removing them; it’s nearly impossible.”

Abdul-Ahad develops an appreciation for the economy of war, just as he boils with frustration at the nonsensically bipolar narratives imposed on reality by Mideasterners and the mainstream Western media alike. In Syria, he hesitates to write about the spread of jihadis in the territories released by the Syrian revolution because “Western journalists and diplomats would argue for a long time that there were no jihadis in Syria, even after the jihadis themselves had announced their participation in the fight.” Then there are the Monty Pythonesque moments: while chatting about Islam with Saudi, Tunisian and Yemeni jihadis in Fallujah on the eve of the American offensive, it suddenly occurs to one to ask why don’t they kill Abdul-Ahad’s journalist colleagues, who are not Muslim.

“We can’t do that now,” he said with a broad smile on his face. “We are in a state of truce with them.”

Other memorable moments in which Abdul-Ahad manages to be present are critical tipping points in life and conflict that lead to dispossession and the kind of refugee movements that westerners became familiar with in 2015. One violent night in Ramadi, as a total of 14 factions battle it out in the streets, the activist hosting Abdul-Ahad decides to abandon his book-lined apartment and white cat, as coalition forces begin a sweep through the neighborhood.

“Quickly, life returned to the dark streets, as men abandoned their houses and ran, everyone in flip-flops and dishdashas, but a few clutching plastic bags and preparing for a long exile.”

There are hundreds such moments of insight spread through the book, opening an unvarnished porthole onto the most private and traumatic moments of a distressed region.

So why is Ghaith Abdul-Ahad not a household name? Why are so many war correpondents under the radar? Perhaps because the focus is often not so much on the harsh and hopeless truth, but on attention-grabbing, cathartic narratives, purpose-cut to the audience in mind. Maybe it is still all about “finding a ‘western angle’ that still views the east through the prism of the west, rather than on its own terms,” as one regional correspondent wrote me.

Perhaps even while it’s about “them,” it’s ultimately still all about “us” as western observers.

Insightful analysis, accurately illuminating how the lens of orientalism skews not only reports of wars but of the war reporters themselves. “