A new exhibition at the Institut de Monde Arabe offers an expansive view of Palestinian art, culture, identity and history, while exposing the colonial brutality of the Israeli occupation.

Sasha Moujaes

What a thrill to discover an exhibition devoted entirely to Palestine, and what’s more, in a Parisian cultural institution such as the Institut du Monde Arabe. Let’s face it — we’re evolving in a singular context. Between the criminalization of the Boycott, Divestment, Sanction (BDS) movement by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) in 2020, and the banning of a pro-Palestinian demonstration in 2021 at the request of Interior Minister Gérald Darmanin, the hope of serenely evoking the Palestinian question seems lost in France.

We are well aware of the excesses of the rhetoric that often wrongly equates anti-Zionism with anti-Semitism; today, the slightest act of solidarity with the Palestinians runs the risk of being associated with a form of anti-Semitism. Far from serving the fight against anti-Semitism and all forms of racism — in France and throughout the world — this conflation is fallacious. It persists both in ruling circles and among the general public, with the exception of a few pockets of resistance concerned with the dignity of Palestinians and respect for international law. In such a political climate, it is gratifying to see a major exhibition on Palestine taking place.

What Palestine Brings to the World, on view at the Institut du Monde Arabe until November 19, 2023, offers a rich panorama of artistic creation in connection with Palestine. Placed in dialogue on thematic, formal, and aesthetic levels, the works exhibited and the museographic tour shed a welcome light on daily realities in Palestine, or at least enable us to grasp a fragment of them.

The exhibition is divided into three sections:

• Palestinians in their Museums, a selection of works from the collection of the Palestinian National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art. These works will eventually be moved to East Jerusalem, capital of a future Palestinian state. In the exhibition, they resonate with works from the collection of the Arab World Institute and the virtual Sahab Museum.

• Images of Palestine. A Holy Land? An Inhabited Land! contrasts Orientalist images from the late 19th century with contemporary photographs by Palestinian artists: on the one hand, it demonstrates the vision of Palestine as a mythologized and fantasized holy land (which contributed to the famous Zionist slogan “a land without a people for a people without a land”) and, on the other, the true character of Palestine today.

• Jean Genet’s Suitcases, an immersion in the writer’s literary work and political commitment, particularly his activism on behalf of Palestine. This exhibition is co-produced with the Institut Mémoires de l’édition contemporaine.

As the aim of this article is not to go through the exhibition’s entire inventory, we offer you a selection of some of its works.

The subversion of artistic materials

In Palestinians in their Museums, pieces by artist Hani Zurob, notably the diptych “ZeftTime N.1” (2020), created with tar and glass in a mixed technique on wood, and “Standby n.16” (2008), created with tar, henna, and pigments on canvas, are particularly striking. The use of tar as a material evokes a well-known Levantine expression, “al hayat zeft” — literally, “life is tar.” The expression alludes to the darkness and harshness of life.

In addition to its metaphorical dimension, the choice of this material also aims to avoid the use of paint from Israel. In this sense, Hani Zurob’s method evokes the boycott approach advocated by the New Visions art movement. Founded in the late 1980s by Slimane Mansour and Nabil Anani, whose works can be admired in the exhibition, this movement actively promotes the boycott of art materials imported from Israel into the Palestinian territories. The aim is to promote the use of natural materials such as coffee, henna, and clay.

Another work in the exhibition stands out for its technical innovation. Artist Abdul-Rahman Katanani‘s highly unusual “Tornado” (2020) repurposes barbed wire. Living in the Sabra neighborhood near the Shatila camp in Lebanon, he draws on elements of the repressive urban environment he grew up in.

Marion Slitine, the exhibition’s associate curator and an anthropologist specializing in contemporary Palestinian art, explained in an interview with The Markaz Review that this work plays a pivotal role in the exhibition, between the first room, which focuses on general works by artists from all over the world, and the second room, which concentrates more on the plight and suffering of the Palestinians. For her, “this piece is highly symbolic,” as it demonstrates that “through a contemporary and conceptual aesthetic language, it is possible to reach an audience beyond the Palestinian, Arab, and Arabic-speaking public alone.” Abdul Rahman Katanani’s approach allows her to address the issue of Palestinian rights in a very subtle way, without giving in to the so-called miserabilist rhetoric often associated with the subject. Like the exhibition as a whole, “Tornado” goes beyond the classic paradigm of presenting Palestinian rights in terms of the “victimization/heroization” dichotomy.

The “right to imagination,” the last bastion against colonization

Echoing Palestine’s National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, another museum in exile unfolds in the exhibition space. Slitine explains that the virtual Sahab Museum is the fruit of collaborative work by 14 young artists, almost all born and living in Gaza, under the impetus of the collective Hawaf (margins in Arabic). Founded by Mohamed Bourouissa, Salman Nawati, Mohamed Abusal, and Sondos Al-Nakhala in 2021, the collective’s mission is threefold: to preserve Gaza’s artistic, architectural, and archaeological heritage; to bring its territory out of the margins and isolation; and to create a future museum in Gaza Strip, once the blockade is lifted.

The name of this virtual museum, Sahab (“cloud” in Arabic), refers to a “cloud” that would store data and preserve Gazan cultural heritage, as well as to the only secure space within an Israeli-embargoed territory in which Gazan artists might find refuge. The piece exhibited at the Institut du Monde Arabe is the fruit of several months’ work between February and April 2023. It is meant to be a donation from the young artists to the future museum of their city. The long canvas, one of the museum collection’s first pieces, depicts an extended path without walls or borders, along which people can move freely.

According to Slitine, the Sahab Museum may be based on virtual reality technologies, but its virtuality is no substitute for its physicality. She adds that the very fact that this painting managed to get out of Gaza is quite a feat. In fact, given the restrictions on movement and circulation of individuals and objects, it was necessary to develop evasive strategies to transport the canvas to France. However, she points out that this work, measuring one meter by two, is the exception that proves the rule. Artists in Gaza are subject to the vagaries of the embargo, and often have to produce smaller works in order to transport them in car trunks. Slitine hopes that this work will bring home the harshness of the confinement of bodies and works of art in Gaza.

Lastly, in her view, this project fits in with the definition of museum articulated by Françoise Vergès in her book Programme de désordre absolu – décoloniser le musée, as it “challenges the universal, highly vertical museum, where objects are sacralized and immortalized [at the same time as they are] frozen, ‘mortalized.'” The Sahab Museum collection is “founded and built by artists, by citizens, by members of the collective […] based on horizontality.”

What’s more, the Sahab Museum is a long-term project scheduled to run for years. “The idea is not to do a one shot, but [to enable young Gazan artists] to accompany each other” so that they can “take hold of the project” and create a “real utopia,” Slitine says. The Sahab Museum must be a space where we have the “right to practice imagination.” For her, taking away the right to imagination is “the most extreme degree of colonization.” Claiming this right, claiming the practice of imagination, “is also resistance, not in the romanticized sense of the term,” but in the very concrete sense of “resistance to colonial practices that try to eradicate this right.”

The question of the “right to imagination” as resistance to the colonization of the mind is also prominent in Maen Hammad‘s “Landing.” This photographic series is exhibited in the second part of the exhibition, Images of Palestine. A Holy Land? An Inhabited Land! and aims to document the skateboarding scene in Palestine between 2014-2015. In a recent interview we conducted with the artist, himself a skateboarder, he said that the sport allows one to be “transported” on a “physiological and mental” level to a “place of joy.”

Hammad points out that this sensation is particularly important in Palestine, where it is very difficult to find “pockets of joy or camaraderie with friends, in the very basic human sense.” For a person who practices skateboarding, ledges, stairs, and all outdoor spaces are perceived not as mere spaces but as obstacles, where it is possible to perform an “interpretive dance.” Overcoming an outdoor obstacle as a skateboarder means dominating the space. The “Landing” project underlines the specificity of Palestine: in a context of land colonization, the domination of space is of major importance.

This series of four photographs resonates intimately with other works in the section of the Images of Palestine. A Holy Land? An Inhabited Land! such as “Parkour in Gaza” (2011) by Shady Alassar, “Occupied Pleasures” (2009-2013) by Tanya Habjouqa or “A League of Their Own” (2011) and “Gaza’s Rainbow” (2009) by Eman Mohammed, which highlight Palestinians’ right to leisure and to dream, even in a context of occupation and colonization.

Combining art, archives, and satire to question Palestinian history

The section Images of Palestine. A Holy Land? An Inhabited Land! highlights the efforts made by Palestinians to reclaim a land of which they have been robbed. By juxtaposing 19th-century images that confined Palestine to an idealized, Orientalist idea, with contemporary photographic works by Palestinian photographers, the vitality of the Palestinian territories, often overshadowed in our perceptions by the dynamics of occupation and colonization, appears immense. In a video presented alongside these images, Elias Sanbar, writer, former Palestinian ambassador to UNESCO, and curator of the IMA exhibition, explains that in the European colonial mind, Palestine is considered a “disappointing” land, “tainted” by the presence of Palestinians. Orientalist iconography in fact paved the way for the expulsion of the Palestinians, deemed unworthy of the Holy Land.

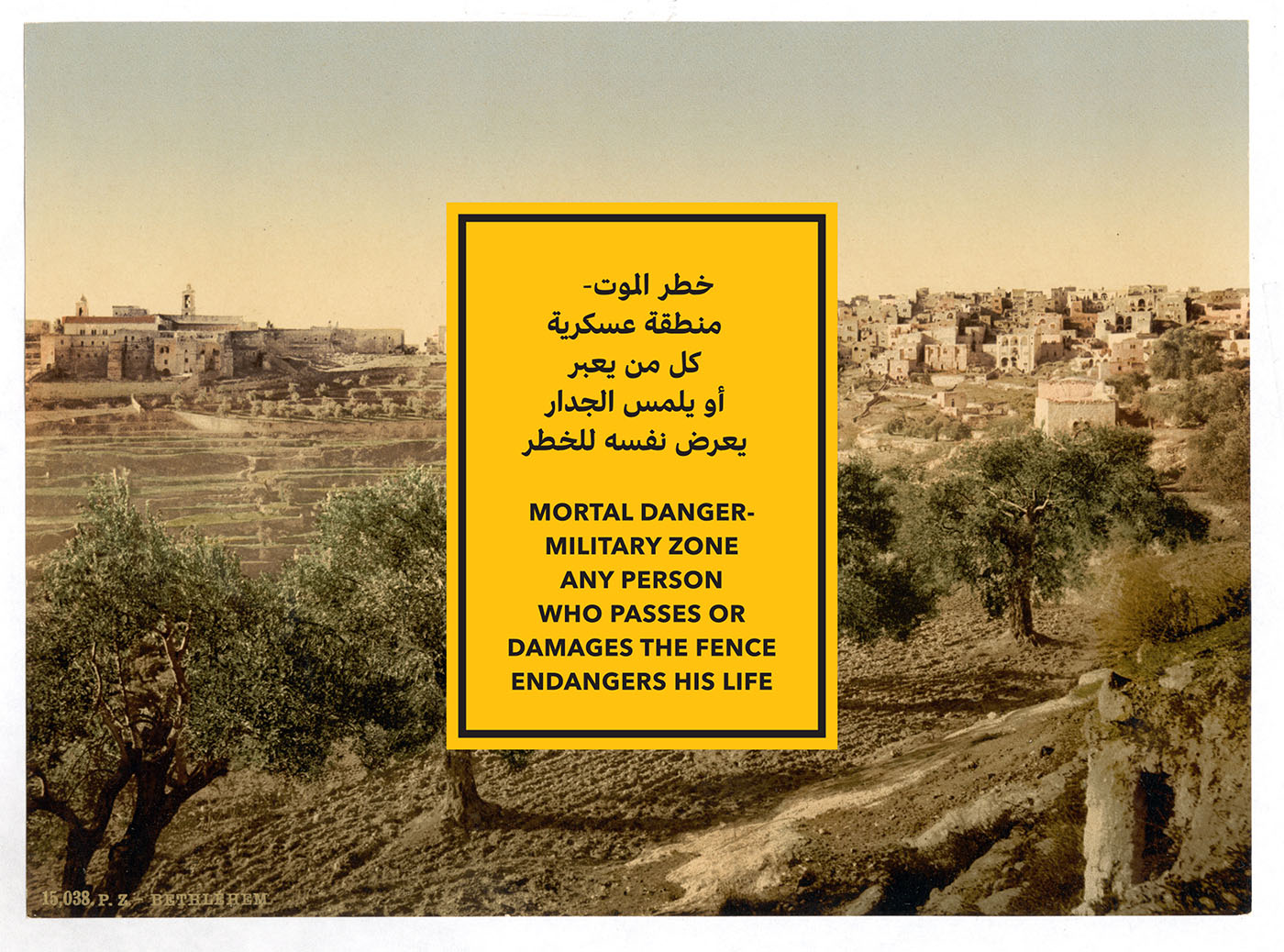

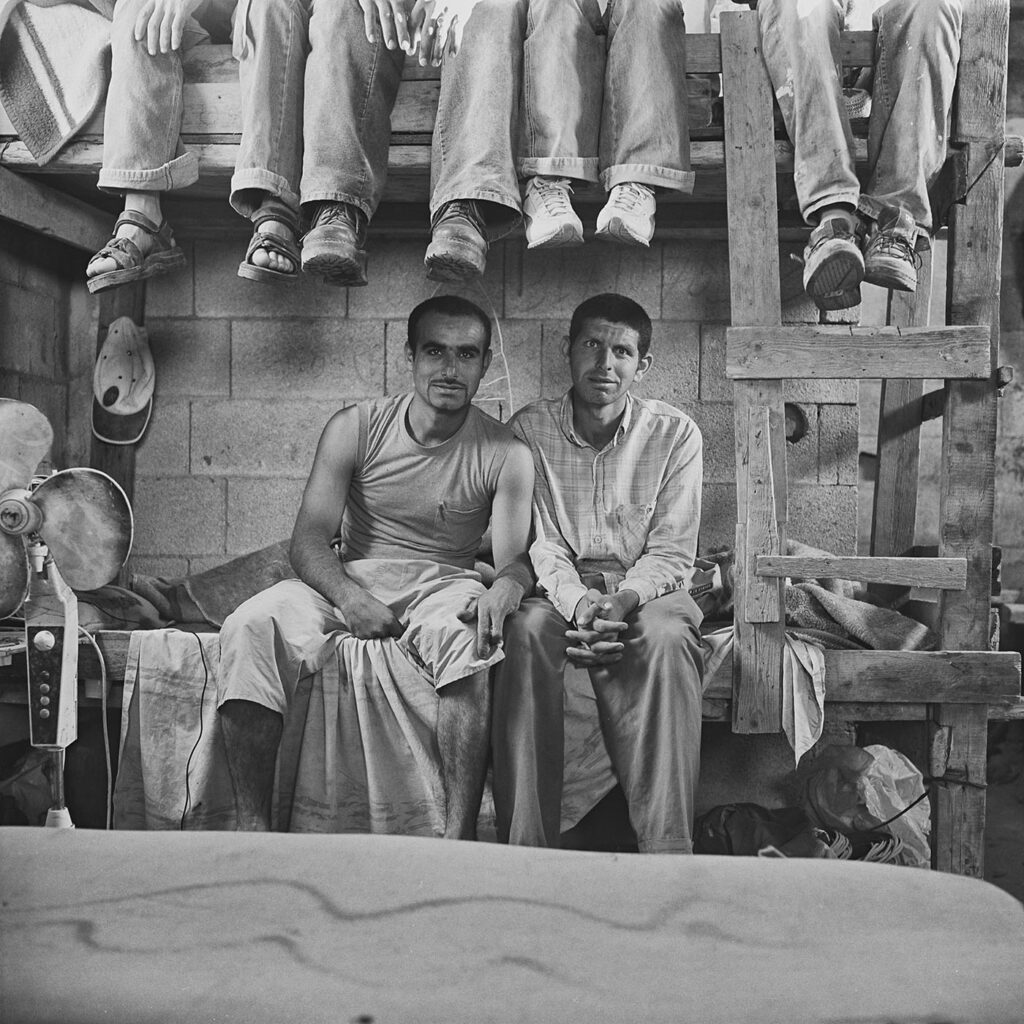

Artist and collector of objects, Hazem Harb has taken these images and subverted them in his “Military Zones” series (2019). He has incorporated the yellow stop signs installed by the Israeli army throughout the country to restrict the movement of individuals— particularly Palestinians. In a recent interview, the artist tells us that the idea for this project came to him while he was on a video call with his friend in Jerusalem. She was near the separation wall when, suddenly, he noticed a road sign (similar to those in “Military Zones,”) closing the access to a forbidden road in the background of his screen behind her, even though she hadn’t paid any attention to it. This type of sign exists everywhere in Palestine, and its presence is now completely commonplace in the minds of Palestinians.

Hazem Harb points out the absurdity of banning visitors from such a magnificent landscape. “Imagine putting up a similar sign near Lake Como in Italy or the Seine in Paris,” he points out. For Harb, the normalization of such an object in public space is “satirical.” Unsettled by the almost “comical” nature of the situation, he takes a screenshot of his friend with the stop sign in the back. As we can see in the image above, he uses “black humor” to reuse old Orientalist images, in which he inserts these signs, in order to question history and reappropriate it.

“Military Zones” enters into a dialogue with several other pieces in the Images of Palestine exhibition. The horrors committed by Israel are depicted as so absurd that they sometimes take on an almost comic dimension. Black humor, for example, is to be found in the photographic installation “Gaza Houses 2008-2009,” created by Taysir Batniji with the help of journalist Sami Al-Ajrami, which features descriptions of houses destroyed by Israeli bombardment of Gaza that same year, in the style of real estate advertisements.

The reappropriation of Palestinian history through archives, so central to Harb’s work, can also be seen in Rula Halawani‘s audiovisual installation “Jerusalem Calling” (2015). In it, she uses archival images of Jerusalem’s Old City. Her aim is to preserve the memory of the city’s perpetual transformation. At the same time, she reflects on the “de-Palestinization” of East Jerusalem caused by Israeli colonization.

Confinement at the heart of contemporary Palestinian art

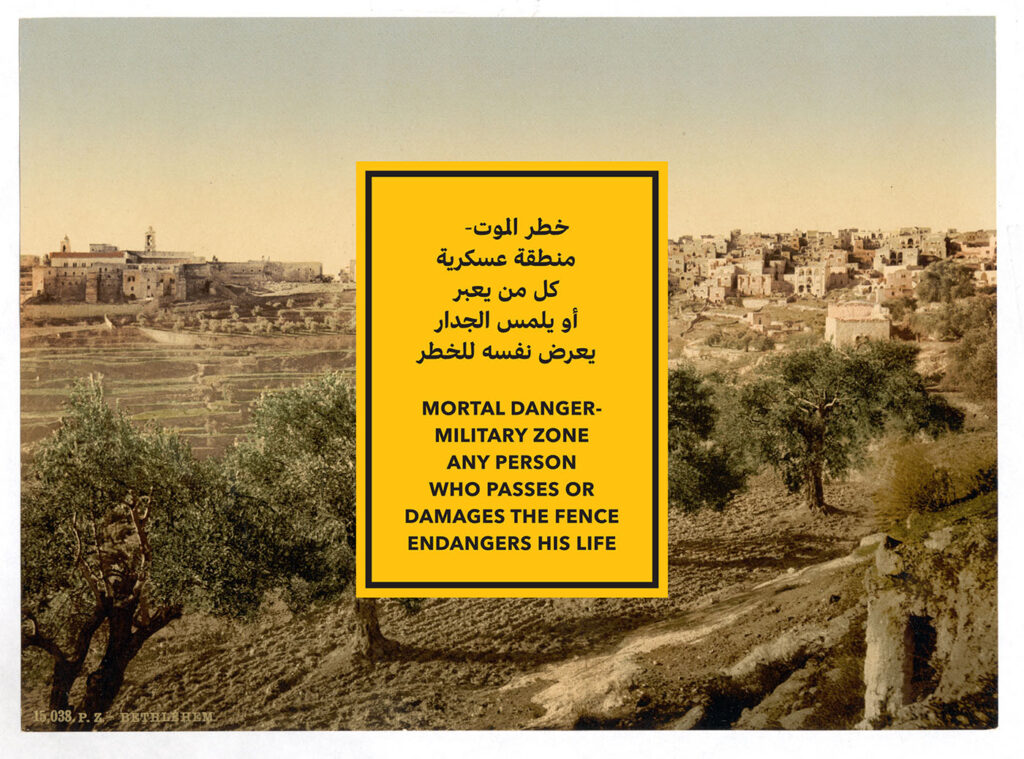

Through the photographic triptych and sound installation “The Braids Rebellion” (2018), Palestinian photographer Safaa Khatib set out to tell the story of young Palestinian women inmates at Hasharon prison, most of them minors. In 2017, they responded to an appeal for hair donations for cancer sufferers, heard on local radio in the prison. In a show of solidarity, they decided to cut off their braids, although they weren’t sure they could smuggle them out of the prison. In an interview with TMR, Safaa Khatib explains her approach behind this photographic project, which comes at a time when the number of minors detained in Israeli jails is increasing.

In 2018, she met a young girl recently released from Hasharon prison. The girl showed the photographer a handmade magazine produced by the prisoners, in which the photographer discovered 13 braids adorned with small pink bows, symbolizing breast cancer. Rather than take pictures with a camera, she opted to use the photocopier in her Jerusalem apartment, set up as a darkroom. For her, the photocopier reduces the distance between these prisoners’ stories and the people contemplating the photographs. She sees herself as a simple medium for telling this extraordinary story. By inserting the braids into the camera left open, she takes photographs of the hair, three of which are currently on display at the Institut de Monde Arabe.

The effect that the white light of the photocopier produces — normally intended to illuminate the documents to be reproduced — symbolizes life, while the darkness of the darkroom evokes prison. This particular use of photocopying becomes a striking metaphor for the prison experience of these young girls, cut off from their families and the outside world, their bodies evolving in a reality suspended between life and death. Five years on from this photographic series, Safaa Khatib is still deeply moved by the solidarity and resistance of these young inmates. She vows never to let their story be forgotten, and is determined to continue her work.

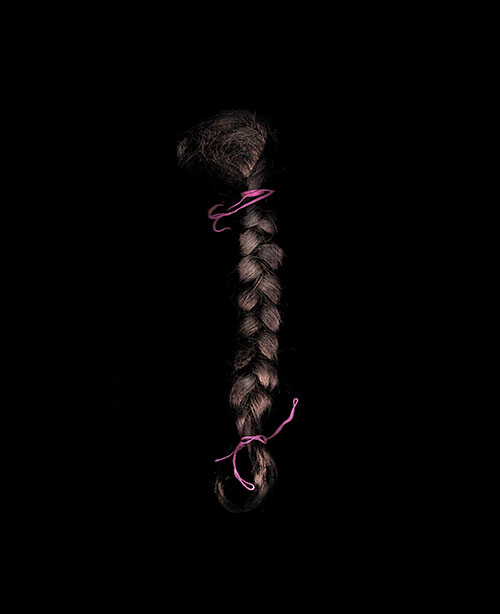

Raed Bawayah‘s autobiographical photographic series “ID 925596611” takes another look at confinement through the medium of photography. His photographs are the fruit of social research into the living conditions of so-called illegal workers in Israel. Produced over a one-year period in 2004, this project was born in the context of the second Intifada, which erupted following a controversial visit to al-Aqsa mosque by the then-Prime Minister Ariel Sharon. The Israeli government’s response to the uprising was a series of repressive measures, including restrictions on the movement of Palestinians. To survive, many Palestinians were forced to work illegally in Israel.

The photographs show how these individuals, often employed in the construction and agricultural sectors, risk their lives by crossing the Green Line. The extreme danger involved in crossing the Israeli-Palestinian border leads them to settle nearby for work lasting two to three months, before returning home by crossing it again to reunite with their families.

Raed Bawayah himself experienced the perils inherent in this situation. Originally from Quttana, a village in the West Bank, he was “illegally” studying photography in East Jerusalem and had to brave the restrictions imposed by the Israeli authorities. One day in 2003, he was arrested by the Israeli police and detained for three weeks. In his cell, he became aware that his fellow prisoners were workers who had risked everything to make a living in Israel. This led him to spend an entire year criss-crossing Israeli territory, documenting the phenomenon. A temporary one-year permit allowed him to travel to Jerusalem, Tel Aviv and other cities, capturing the silent stories of these workers.

The theme of confinement is recurrent in Raed Bawayah’s images. His work sheds light on the conditions of confinement of people located on the margins of society, with whom he forges intimate links before using his lens: Palestinians in his native village, patients in a psychiatric hospital, women working in salt mines in Colombia, or gypsy populations in France. According to the photographer, the images he captures are more than just photographs; they are windows onto the whole world, a world without borders. For him, photography is “a free medium that lives without borders and speaks to everyone.”

What does Palestine bring to the world?

“This exhibition is a framework for understanding contemporary injustices, which can be understood beyond the experience of Palestinians, even if there are things specific to the territory,” explains Marion Slitine. Far from obscuring the dynamics specific to the Palestinian context, this cycle of exhibitions offers a different take on Palestine. The exhibition looks beyond Israeli colonization and occupation, even if these play an essential role in the lives of Palestinians.

Through the diversity of its themes and artistic forms, the exhibition highlights the universal character of contemporary Palestinian art — a universality that is not Eurocentric, as found in European museums, but rather plural or pluriversal, respecting the plurality of worldviews. We can also see the extent to which contemporary Palestinian art can break with the hegemonic discourse on Palestine and offer alternative perspectives on the world. Characterized by its subversive force, it truly shows “what Palestine brings to the world.”

However, the national context in which this exhibition takes place is not insignificant. The hostility surrounding the Palestinian question is palpable in academic, artistic, and political circles. Bringing Palestine to the forefront of French public debate is a major challenge. However, while Slitine acknowledges the “tension” that Palestine arouses in France, she points out that, since the opening of the exhibition at the end of May 2023, its reception by the French public has been generally positive. In short, What Palestine Brings to the World manages to negotiate Palestine’s place in a cultural institution in France, and we can only rejoice.

The writer thanks Marion Slitine, Maen Hammad, Hazem Harb, Safaa Khatib and Raed Bawayah for taking the time to speak with The Markaz Review.