In Frankenstein’s Mirrors, Abbas Baydoun presents a collection of autobiographical vignettes that reflect—and reflect on—moments both in and out of time. Each chapter captures an experience, however fleeting, as it ripples around the author’s life in often unexpected ways. Though self-contained, the chapters work together to form a more perfect whole, to elucidate unnamed relationships and to paint the portrait not only of a particular man but also of the subjectivity he comes to represent.

We enter “Gluttony” just as the narrator finds himself awake and covered in cold sweat. We don’t know why, only why not: it wasn’t the heat and it wasn’t a dream. The unsettled states of the opening paragraph seem to set up a traditional narrative arc. Indeed, the story is subsequently said to begin with a box of chocolates. Yet, what follows is not a story in the traditional sense but rather a discursive stream carving its way through a canyon of sensuous detail. Baydoun’s attention to the smallest of things borders on excess, while his lack of exposition asks us to accept his world as a given. Who is this Dunya whose chocolates promise the narrator what others seek out in books? Again, we don’t know. But from the very beginning, we are immersed in a uniquely material world, which—like Dunya’s namesake—bridges the gap between human experience and spiritual ineffability, imagination and inspiration. A world that evokes bitterness, arousal, and of course gluttony.

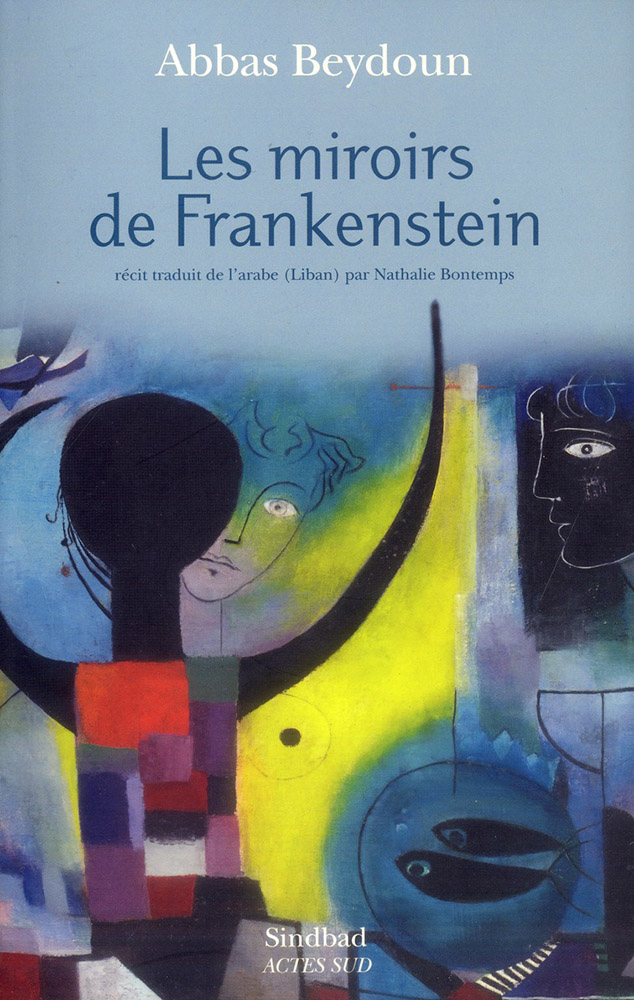

Abbas Baydoun

Translated from the Arabic by Lily Sadowsky

I awoke, my brow clammy with cold sweat. My blanket was light, and I had worried it wouldn’t be warm enough. I had wound it around my body to guard against the cold night but had dozed off in front of the TV and couldn’t muster the energy to get up and get another. All through the night, I’d had the funny feeling that I wasn’t covered, yet here I was—awake, my head damp from cold sweat still seeping from my pores. Each time I wiped it with the sleeve of my pajamas, it flowed anew. Was this because of a dream? The thought crossed my mind, but I didn’t remember dreaming and I didn’t remember forgetting a dream. In fact, my dreams had been waning recently. Was this because my memory was receding? The thought also crossed my mind. I awoke with a bitter, almost funereal feeling. An idea had planted itself firmly between my teeth and in my throat: life begins as a loss and, from the outset, resembles death. I awoke with a stiff erection too, one devoid of desire though I’m still young and full of promise.

Layering the inside of my head were deposits of thought that accumulated as I churned. I was confused about where to begin. I felt that my engorged penis wouldn’t bring glad tidings, that it was the trace of a bad dream—one that had all but completely evaporated from my mind, one that had left behind only bitterness. I tried to bend it in my hand, beat and break its tumescence. And actually, I succeeded. But only for a moment before it stood anew. Then I remembered the three unrelated thoughts in my head: the bitterness, the erection, and the whisper of gluttony. I played with myself, imagining that I stood before three options and had to choose. I discarded the first and the second, deciding to take refuge in the third, at the very least as an exercise in shrugging off my morning funk.

So the story begins with a box of chocolates that Dunya had given me after I bought the three books she had asked for. Christmas chocolates. Brightly colored orbs in a transparent box. I don’t like to see foods through their packaging. Well, I don’t like to see them packaged in plastic. Plastic’s okay for tools, even for clothes. Toothbrushes, for example, or shower heads or shirts.

They look expensive in that clear casing, more beautiful than their functions would suggest. It’s added value, before we extract them from those attractive arrangements and transform them into waste. Foods that will soon be circulating through our bodies should be treated like our bodies themselves: protected and preserved, guarded and covered. It’s better that they be kept in boxes, where they can lie in wait for us to share the secret bond of our bodies with them. The constant spectacle, beneath the watchful eyes of all, makes them common. And it makes us feel that our eyes have debased them.

They look expensive in that clear casing, more beautiful than their functions would suggest. It’s added value, before we extract them from those attractive arrangements and transform them into waste. Foods that will soon be circulating through our bodies should be treated like our bodies themselves: protected and preserved, guarded and covered. It’s better that they be kept in boxes, where they can lie in wait for us to share the secret bond of our bodies with them. The constant spectacle, beneath the watchful eyes of all, makes them common. And it makes us feel that our eyes have debased them.

The chocolates in the box were round. I don’t like when chocolates are round either. I imagine them square or rectangular, but round—no. I don’t like round balls of meat or ice cream. They’re too perfect, feel too whole to be put in our mouths. They make us guzzle instead of gnaw. We start by breaking them down like doors that stand in our way.

The box that Dunya gave me was for Christmas, and Christmas was close. But I didn’t wait. I opened it, taking one of the chocolates and placing it between my teeth to taste. I didn’t feel it breaking. As soon as it met my saliva, the chocolate readily gave way—its skin melting with the touch of my tongue. I didn’t apply any pressure. I simply sensed its spherical shape, and it collapsed on its own. I heard the fine, permeable interior break in my mouth. Of course, I didn’t hear it with my ears. It wasn’t, in essence, a sound. Rather, it happened within the wholeness of my being. I could also see—with something other than my eyes—that permeable body which had just disintegrated. The flavor took flight as if it had been liberated, but its delicacy and the speed of its disappearance made it seem like a figment of the imagination. The orb had dissolved immediately, but I had penetrated the gushing, doughy interior that was—so it seemed—the very truth of chocolate. Its flavor was concentrated, deepening and thickening with every movement of my tongue. In the end, I hit upon a solid almond. This was the core, which I recognized in the silence and splendor of knowledge. The tongue was no longer the only messenger capable of hearing, seeing, and feeling for me. My tooth had hit the almond bone, and there’s a certain pleasure to bone meeting bone. It’s a pleasure of mine to anticipate pleasure. I can’t stand the pace of most things. To find joy in a song, I rush to its end. I rarely let anything play out. I’m waiting for a pleasure that doesn’t bring duration to mind. Time persists, ever stronger, and my sense of it is overwhelming. But a melody seemingly without speed or scope may arise in a single moment, a melody that is not captive to time but is itself captivating. That’s how I take pleasure in eating. Quickly. Not clinging endlessly to flavor, not transforming it over time. I’m satisfied with the first taste, pushing the morsel subsequently into my stomach.

Sometimes I arrive at the true taste gradually, as it grows stronger and deeper with each bite. It is then that I lose control. It is then that I cannot stop.

In Dunya’s box were three colors, ten chocolates each, lined up in six rows. I wanted to try one of each and leave the rest for Christmas as Dunya had intended. But I lost control. The critical moment came when I hesitated, considered the next piece, and sensed that I wouldn’t be able to deny myself. Still, I knew that I should wait. But it was as if I were being forced to continue—a pleasure punctuated by light sorrow. I remember the caramel of youth. It was hard, so I had to start by tasting its surface, stripping it with my tongue again and again until it became rougher, more permeable, resembling a tongue itself. Then I could start to soften and soak it until its taste became stronger. It was long, analytical work, in which the milk and chocolate elements were unearthed. The taste didn’t change but thickened more and more until finally arriving at its essence. The chocolates of Dunya were even more delicious. The solidity, the finesse, the gushing—one after the other in a single, atomic moment—sharpening then disappearing into blood and the imagination.

As a teenager, I tried to keep away from sweets. I weaned myself off them early, unable to stand those things that reminded me of my childhood or brought me back, somehow, to my mother’s breast. The union of milk and sweets often takes place precisely in chocolate, and in my youth, I abstained from everything that contained milk. While waiting at the alley’s mouth for the confectioner, sucking sugary nectar from popsicle sticks and dreaming of two full jars of sugary Leblebi—those candied chickpeas—well, sweets were childhood itself…

My melancholy was the first sign of maturity. The more I plunged headlong into it, the more it seemed that I was becoming an adult: it is then that we’re sufficiently severed from the mother’s milk, even if we’re less happy because of it. Manliness seems lonely. Truly lonely. Its desires, which are afraid of themselves, remain thirsty and restless like desert plants. Nothing compares to the complete pleasure of sucking on barley sugar or eating a serving of sugary Leblebi. Then it seems that there’s no better escape from depression than to drown our hearing, sight, and appetite in a plate of sweets. But relapses are met with repercussions, and as soon as we start again, we cannot stop.

But why sweets and only sweets? Every time I contemplate a dish, I find true perfection.

The invention of a meal, any meal, must be an inspiration—but one that is never wrong. Each time, as if by instinct, we discover something that is right—and provably so. Each day, in fact, brings new proof. How did they think to fry coriander with garlic? Surely, a discovery like that is no less important than the discovery of Earth’s gravitational pull. Our world has been changed ever since. Lunch has become something else. How did they think to mix oil with garlic and tahini? Surely, imagination alone is insufficient. Inspiration has got to be involved: light shot into the heart. Those who search for miracles, for proof of God’s existence, are better off searching in this realm. People can construct countless arguments, all of which would be open to debate, but who can deny an onion with its many layers and thick aroma? Who can deny the testimony of a piece of cheese? The ingredients yearn for one another, but it takes a great instinct to know it. No apostles of spiritual magnetism will find better evidence. First of all, they’d need to be psychic. It takes tremendous discernment to see that a plant in Asia yearns for another in Alaska and that the universe is actually one giant magnetic field. We’re only now discovering it. We’ve spent ages in this world, but it’s only just beginning. There’s no telling what will happen with the progress we make. Maybe the elements will unite at a single pole or maybe in a large network. Either way, the world will take its true form. A religion could start in the kitchen.

I remember a friend telling me almost thirty-five years ago that fat is what makes food taste good. He must’ve been thinking about food the way we think about God. He must’ve been looking for a prime mover and found it: Fat is the Creator of taste. This could be a first cause, a potentiality with which to prove something greater. At the time, I thought he was right. There must be a single principle that governs this vast amount of flavor. Today, I’ve lost my faith in the idea. We could contemplate fat without going to a restaurant. Then—and who knows, I’m no expert—couldn’t we produce a strong flavor without any fat at all? Still, like that friend, we may be led astray among the tastes. No other such network exists except for that of emotions. We’ve thought a lot about feelings but haven’t done the same with foods. In Arabic, and maybe in French, not one word exists for the sole purpose of describing alimentary pleasure. There are more than a few for sexual pleasure, but alimentary—no. We simply say that food is good or pleasant. To be good and to be pleasant—these are common. There’s no special word for that pleasure which arises from savoring eggplant seasoned with garlic and lemon or from a piece of liver soaked in pomegranate juice.

Language is incapable of being everything, or so I think. It misses so much more. It misses the essence of our existence. Sex, too, is mostly speechless. How can language be our history? As long as we keep living most of our lives outside of words, couldn’t we consider ourselves essentially mute? We talk when we don’t feel, and we feel when we don’t talk. The distance between the taste of a grape and the taste of a mango is great, but each is a miracle in relation to the other. How to express that? I suppose it’s beyond us. There’s nothing superfluous about a cup of tea in the afternoon, but we treat it with much less gravity than reading the newspaper in the morning. But reading the newspaper isn’t pleasant because of the information it contains but because of something else, something entirely like a cup of tea. The matter requires analysis yet to truly begin.