An Artist’s Exploration of Saida’s Hammam Al Jadeed

Ziad Suidan

Having no defined feature

A labyrinth knows not itself

No gate designating from where to enter

Congruent to emptiness

Still, complicit with the echo

(Thanaa’ Atwi, trans. Ziad Suidan)

Dizzying as it is marvelous, treacherous as it is evocative, a labyrinth has been said to be at times a space where multiple stories and their attendant narratives coexist in tense proximity. Yet, again, labyrinths might be said, as Italo Calvino suggested, to be a “honeycomb in whose cells each of us can place the things he wants to remember” (Invisible Cities, “Cities and Memory Pt. 4”). True archives of meaning, they evoke still other memories. The storehouse is only purified by force of will. After all, a honeycomb signifies something sweet and sensual; for a hammam, a place at once suggestive of relief, shedding more than inhibitions, it is also a place under threat today, when our climate catastrophe threatens what some scientists have called the most essential of creatures for life: the bee. Sounds past and present buzz and echo though the chambers of the hammam, which is now reasserting itself against closure, amnesia, and indefinite anticipation. Labyrinths are places, perhaps, because of the tight corners and passageways which look familiar yet are all different, where detours and retours can cause confusion in the mind. Each trace leads to another in a chaotic maze of possibilities.

This all opens the door for Tom Young to conjure up an archive of Saida’s 300-year-old Hammam Al Jadeed, whose trace lies in its architectural presence and the oral testimonies of residents who remember it before it closed in 1949 [see below video]; a trace whose presence is absent from any accessible archive: until now. But what, where and how has now arrived? Before entering the re-opening of the hammam itself, delays have occurred by what some might call the labyrinthian trials for Lebanon which Tom Young calls home. Those very labyrinthian echoes call up mythos that must find their historical and political parallels today. In Greek tradition, the labyrinth was a structure built by an artificer for the king to entrap the beast, the minotaur. Today, that minotaur in Lebanese socio-political history has situated the everyday Lebanese and marginalized communities in a tangled web of sectarianism and instability. It is not just the way that corruption and Coronavirus have combined to bring about a dire economic crisis, but its struggling healthcare system that shuts out the most vulnerable.

This project at least can bring soothing and freely accessible lightness to counteract the trace of suffocating sufferance. On returning months later to the site, the labyrinthian structure of the hammam will offer a time to suspend and transfer grim realities of the present day for reminiscences of revolutionary potential that evoke Saida’s particular resistance to Lebanon’s governing monstrosity. This is achieved through a tactile sense of evocative smell, chiaroscuro between painting, architectural form, and built environment. It is that evocative pull that will invite us to escape into forgotten histories, mythologies, flavors, and market traditions that too lie at the edge of oblivion.

For an artist, absence can be just as evocative as presence, it can conjure the wonders of a location’s possibilities, competing archives of memory, and the ever-present challenge of sensual pleasure set against the realities of environmental and economic crisis. The Hammam al Jadeed is located near some of last year’s demonstrations, during an attempted revolution that still has intermittent eruptions today. It was a movement that reminded us that before entering the frame into forgotten magnificence, present realities must be encountered. Young has painted such realities in a powerful blaze, a blaze that sparked off nationwide. People had had enough of being ignored, the austerity measures that raised prices of health care and living to a point where the governance of Lebanon, such as its corrupt status is, had to be countered, for the people to face each other, especially the myths of a sectarian society that blocked and still blocks much forward movement.

While a fire burns it also alights, shows possibility for newness. The fire of Saida that Young paints is not that of the reported Intifada that many Lebanese took off from Palestinian images of burning tires but rather a dense gradation of red and orange at a slant burning a Van Gogh sunflower’s texture. It is not just a means to let a nation’s past come to light, it is a prescient indicator that opening the hammam and its histories is an invitation to move forth. In a recent set of paintings in Saida’s orchards, Tom Young has reminded us that there are still sites for pollination, for attractive symbiotic transformation. It is not just that romantic possibility but the fact that an opening and readying of a place that brings with it cool airs of light and shadow, smells and memories, can give us a dizzying sense of elsewhere. And yet all we did is enter a portal, a gate by simple invitation. Furthering that invitation, Young paints a heavenly light shining over the sea beyond a lush landscape of greens and reds of trees dotting the foreground. This promise, seemingly of romantic elsewhere, is welcome after the limitations to movement en masse in Lebanon since Coronavirus spread. The opening of the hammam could not happen at a better time as small groups of people have broken the inertia by rerouting trips abroad to getting to know their country again.

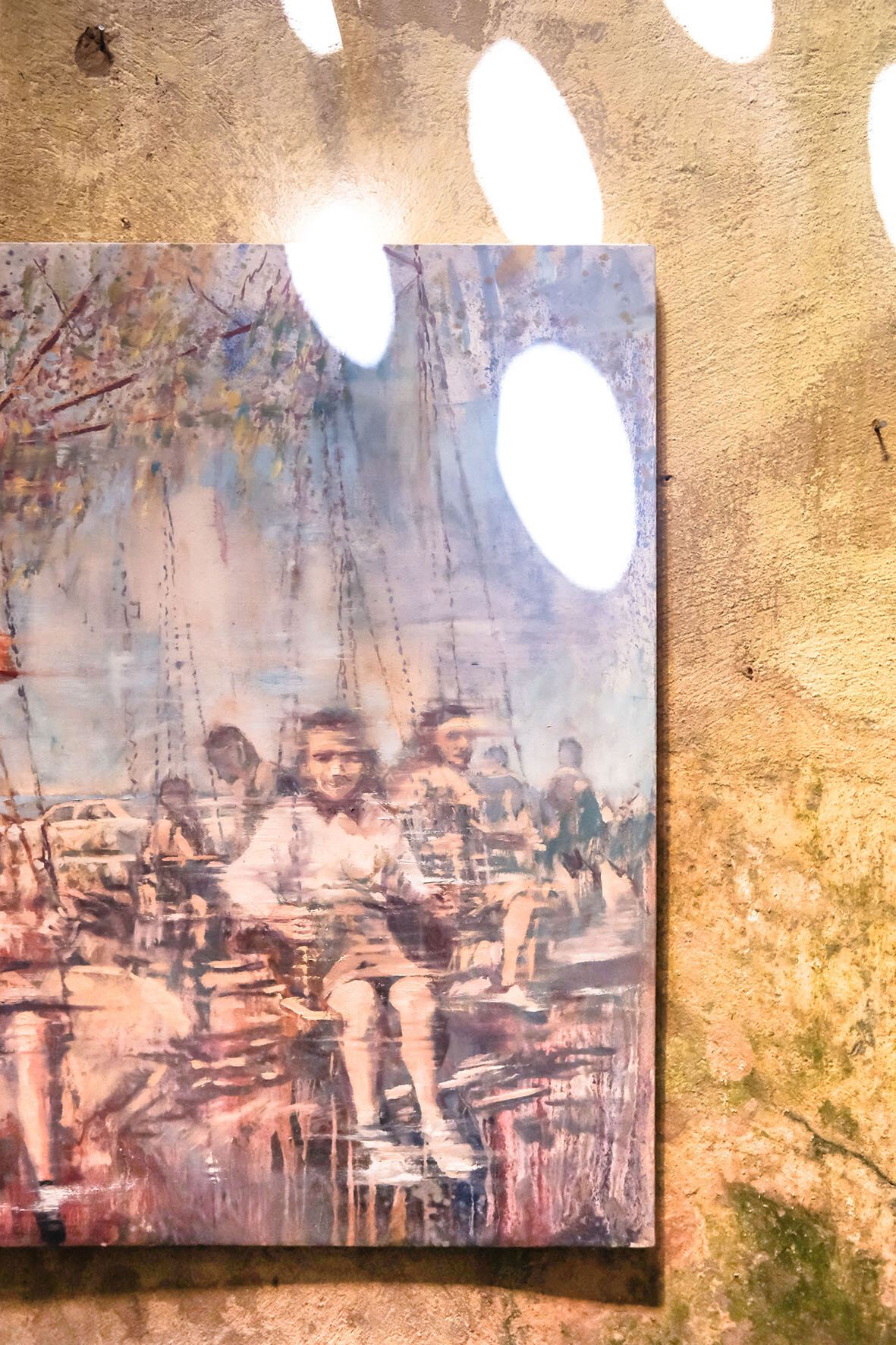

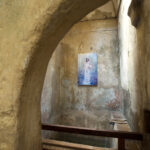

To unearth the stories of the 300-year-old Hammam Al Jadeed, one explores the magnificent entrance hall, small spas and a large sauna, and inside souqs where goods and foods once abounded in dizzying array. At one of the nodal points in the hammam’s labyrinth, Young has situated three paintings that immediately draw the eye to contrasts. The fading walls from years of neglect are put into counterpoint of what may have been blue skies over a brown landscaped history. The pocked ceiling of Islamic architecture that lets light in makes the usual art hall unnecessary. For in relation to Young’s paintings’ chiaroscuro affect to the walls, the light draws the viewer in. Within this cavernous hall and in smaller spa rooms are springs of water that, on a hot summer’s day, is delightful to feel. But the sensual reverie requires careful investigation. To begin accomplishing this, Young conducts a precise architectural survey to establish a technical grasp of the architecture, and then paints from life; he builds up thick layers of oil on a red and blue abstract base, to evoke a sense of temperature. For this is a hammam, a place to experience the transition of hot and cold. He discovers hidden stories by filming oral histories that span memories of a lost Lebanese “Golden Age,” then Israeli shelling, invasion and subsequent years of neglect. This involves a restorative collaboration between the site’s new owner, Said Bacho, and conservationist-artist Tom Young.

While the exhibition Revival fuses oral testimonies with the paintings of lived memory set against peeling walls, it explores awareness of its missing archive of which cannot be recounted with fixed certainty. Sensuality and the tease of full disclosure are only openings that give us a sense of what could be. The tease brings us forward, makes us aware, that some difference to bleak walls are there but to extract what lies beneath is sometimes given to the danger of mouths covered for too long. Is it protection from something forbidden or hazardous? And then who decides what is forbidden? Or protection from a silence that even when removed has to be carefully teased out? Probably both. This is where the artist’s intervention is crucial. Tom Young is ever aware of his presence in place. As a keen student of art history himself, he realizes that the hammam is loaded with Orientalist pitfalls and that an artist following in the footsteps of European forebears must consciously render it in vanishing lines. Young’s evocations of hammam life are rendered in dense textures and thin glazes, as multi-layered as the walls themselves; at times they are painted on site directly blending with the cracked surfaces of the walls as if they are alive. Other works are half erased, unsettling historical stereotypes, the dissemination of “truth” and of the viewing of a moment in time as a settled thing.

Young’s paintings are often filled with absence, and curated to enhance the feeling of that which is missing, what has been and what may be. Perhaps the answer to what is missing lies in the question. Or rather, a question lies inside another question. The perception of one thing is displayed inside the architectural motif which inspired it: to the deep hollowness of the decorative Matryoshka dolls (more popularly called Russian dolls). This deep hollowness lies near sources of water which have since been covered up, run dry, and the niche, itself rendered in echoed receding imprint is of a seashell, familiar as a once-inhabited remnant has been passed around by waves and perhaps saved as a personal memento kept in homes elsewhere. Young’s painting of bathing clogs that have been abandoned, not picked up after a Turkish bath, evokes traces of lives, unidentifiable by class — for the hammam was a place of social equality which served people of all backgrounds. Souls have departed, but their spirits are revived in the visceral texture of the walls. Some paintings open up memories of intimate conversations and celebratory wedding dances, around the splashing acoustics of fountains — hinting at the close proximity of bodies in states of undress, yet the intimate privacy of those conversations and events are protected by the timeless resonance of water splashing on the surface of the fountain pool. Thanks to the care of Said Bacho and the restoration craftsman, Omar Haidar, the same fountain which witnessed hundreds of years of social gatherings has been resurrected. The towering signature painting of the exhibition, The Fountain celebrates this remarkable survival in grand style.

There is something else most pronounced in Young’s studies of ghostly presence inside of the hammam. This is the question of the naked body. Today, that very question, those very tantalizing dares to see, not to avert the gaze, are deferred. More importantly, in this holding ground of Corona, touch of others, of places, even of ourselves is kept at a socially appropriate distance. In a recent collection entitled Art in the Time of COVID-19, “The Touch Stand” — a short story by Lori M. Myers — comes toward its conclusion this way:

I wait, not wanting to force this young man to take part in an action we used to take for granted, the caress of skin on skin, the acceptance of an other. I know its importance. […] These days we’re not allowed. So, I had to set up a stand, hang up a sign, charge a fee.

On top of the health hazards, which compounds an economic crisis, is a culturally specific caution. The local neighborhood of the Hammam al Jadeed is populated by many people with conservative religious values, so the question of bareness requires deft sensitivity.

Tom Young’s paintings have offered a middle ground. In some paintings of bathers, Young makes us lose ourselves in the profile of sensuality, of touch of drapery, milieu, and air, of a play of hot and cold. In one instance, his painting displays a woman upright and flush with the mellifluous light from above that is seemingly equated with the play of the colors from the marbled floor. It does not seem anymore that we are in a hammam that might prescribe some tabooed memories. Rather, we are in a place uncannily inverse to Millais’ portrait of Ophelia from 1851-2 in which melancholia and its attendant morbidity attend an otherwise blanched helplessness.

This compromise to cultural sensitivities has been brought about also by an ethical sensibility in which the artist cannot avoid what happened in this place. Feet at once do not point to sex or gender but rather to invitation, to cleaning the most unremarked of body parts without lewdness, and to a conversation often denied: the relationship of the body to the floor, the ground. How does the body feel against the richly patterned tiles and cold marble?

Young’s paintings of the hammam are an invitation to precious Damascene memory, which today is a treasure given Lebanon’s rapid loss of heritage, and the destruction and looting of art in Syria; paintings of the actual sauna in the hammam depict the silhouettes of those undergoing a massage, and in some cases a sensual touching of the flesh between masseuse and bather. Flesh and the act of touch is central here, rather than the Orientalized sexuality of Turkish baths in bygone European painting. When thinking about the Orientalized history of bare women’s bodies, Young’s use of blurred motion in his art evokes a sense of loss, and hints at destitution and poverty in the streets outside. But this act of touch releases us back into the spaces of the hammam which also brings the outside in: other paintings include the dark mysteries of bazaars, spectral figures of presence just outside the entrance: is it the silhouette of a visitor now, or many years ago? Layers of time converge; is it the long corridors of the souq’s vitality? Is it the fragility of life entangled under electricity wires resembling rhizomatic spider webs? Is it the precariousness of refugee life, which now dominates the old town, where many people now survive with little infrastructure except that which they can patch together? Is it the memory of a past, still living in the mind, in the testimony of its surviving dwellers?

Hammam Al Jadeed in Saida, Lebanon. Artist Tom Young and Said Bacho before Young’s painting of Hajji Zahia Zarif.

In the Absence of an Archive

Testimonies recorded of those who remember the protected sense of utopian existence in the Hammam prior to 1949, also mark its ending in 1949, one year after the karitha (catastrophe) and nakba (debacle) in Palestine. There are many stories about why the hammam closed around this time, from water reaching people’s private homes, thus diminishing the hammam’s essential role, to an earthquake which damaged Saida in 1956, to the sudden loss of custom from Saida’s Jewish community whose members frequented the hammam.

Reading the testimonies which Young filmed as an essential part of the exhibition, an absolute dividing line is made: life before 1949 is filled with love, laughter and marriage, protected by the woman whose memory overlooks the reception room of the Damascene hammam. Young’s painting of Hajji Zahia Zarif is at once matronly as the colors of the peeling wall frame her in painting and by the wall. Zarif, honored religiously but also as manageress and powerful matriarch, is the center of the hammam’s joviality. She not only collects money but makes sure that the eight-year-olds behave themselves in such a tempting setting. Purification is also something central to the hammam from the celebration of marriage and religious crossing over from one family to the other. Esther, the beautiful Jewish bride, whose marriage is celebrated by many, not only for its festive bringing together of the heterogeneous community around the Turkish baths but also for its ritual cleansing and sending of the woman into the home of the husband.

Lastly, life in the hammam is remembered as a social life after schooling before 1949. The women would enjoy the daytime and then the men would come together at night, after work. The children would enjoy the midday respite. Families would enjoy picnic of locally grown fruit and umdadara. It was a place of fun and the delight in becoming clean. With this exhibition, families and children once again fill the empty space with life and creativity. Tom Young pays respect to what has been lost, celebrates the best of what has been, and offers us a dream of what the hammam could become.