“Denied the right to both a father and a culture, she spent the years that followed unraveling the repercussions of these revelations, which she kept contained in a ‘cabinet’ of her mind as she went about her life, until Raad’s death shattered this fragile balance and forced a reckoning.”

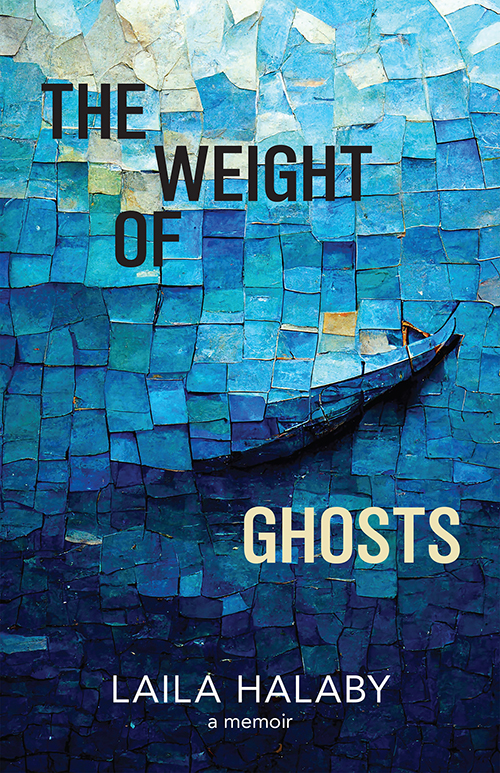

The Weight of Ghosts, a memoir by Laila Halaby

Red Hen Press 2023

ISBN 9781636281346

Thérèse Soukar Chehade

“My story has never been mine to tell,” says novelist, poet, and creative writing teacher Laila Halaby in her memoir, The Weight of Ghosts. “It is squished between other people’s tall tales, glopped onto their secrets and lies.” That may be the case, but the author’s story emerges as fearlessly authentic nonetheless. The Weight of Ghosts begins with the death of Halaby’s older son, Raad. In 2017, on a rainy February night, shortly after two o’clock in the morning, Raad was hit and killed by an 18-wheeler while standing by the side of a highway in Tucson, Arizona. He was 21 years old.

We then learn about Halaby’s early years. Born in Lebanon, she moved to the United States with her (white) American mother as a child. Beginning at the age of 12 and continuing into her 20s, she discovered that everything she believed about herself was a lie. Her parents were never married, making her a ghalta, Arabic for mistake. Her real father was a married Jordanian man with six children who refused to openly acknowledge her. Denied the right to both a father and a culture, she spent the years that followed unraveling the repercussions of these revelations, which she kept contained in a “cabinet” of her mind as she went about her life, until Raad’s death shattered this fragile balance and forced a reckoning.

The memoir is part love letter to Raad, part vindication of Halaby’s right to live authentically. The writing alternates between the two, echoing Halaby’s brokenness as she assembles a new “mosaic” of life and establishes a thematic link between Raad’s death and her splintered life. Halaby addresses him in achingly beautiful poems, maintaining her bond with his spirit through the birds that he loved and that flutter about like emissaries.

For Halaby, writing makes visible what was obliterated yet still persists unseen, and enables her to weave a web of connection around the loss. “Writing saved my life,” she states. With exquisitely precise prose, she conveys the devastating effects of grief and ties together the past and the present, the living and the dead. “Accuracy matters,” the author writes, a moral and artistic statement as well as a map for undoing the damage wrought by the lies that plagued her beginnings.

The sense of being a mistake lingers. To come into the world by accident is to come dangerously close to not being born at all. What do you do with a mistake except try to erase it? In many ways, The Weight of Ghosts balances on the edge between existence and nothingness, a life-death divide where the author grapples with the physical absence of Raad, whose birth wiped away the mistake of Halaby’s own. But then Raad was taken from her.

Such twinning of absence and presence multiplies into a pattern. “There was or there wasn’t,” she states repeatedly, allowing for the realization of both alternatives. This dichotomy — of the amorphous and the tangible, truth and lie, yearning and possession — was passed down, in Raad’s case, through his strong resemblance to his Jordanian maternal grandfather, whose identity had to remain secret, and his Palestinian father, Halaby’s ex-husband. “How does it feel to come from a country that doesn’t exist?” a neighbor in Tucson once asked Halaby’s ex-husband; Palestine, ungraspable yet right over the border from Jordan, and from Lebanon, Halaby’s birth country. “To be denied your story is to know Palestine,” she writes, thereby forging her own connection with that troubled land.

Love opens up the possibility for wholeness while also creating the risk of dissolving into the needs and egos of others. “Because I come from two worlds, I am very good at taking on whatever the person I love takes on,” the author writes. Maleness and whiteness, the conferrers of legitimacy, combine in one man, who becomes the divorced Halaby’s long-term companion. She calls him The White Man I Loved, shortened to TWMIL. Despite the love she feels for him, her “knowing self” has reservations. “White-man-love is a leash keep me from soaring [sic]; maybe it’s just man-love and got nothing to do with white,” she writes a year and a half into their relationship. When TWMIL makes clear that he wants her to revert to being the woman he fell in love with before Raad died, they part ways. She is light years away from the woman she was back then.

Always aware of color as a divisive and oppressive force — “You can’t step into one room without tripping over Brown or White or Black or Non-White or some kind of struggle battling some kind of privilege” — Halaby actively counteracts a racist system by sussing out the individual shades made invisible by it: “I was the opposite of I don’t see color. I was I see all shades of color and that’s where I find the truth.” The truth is that she is “50.7 percent Western Asian/North African, 49.3 percent Northern European.” This level of attention to one’s genetic origins may seem self-involved, but pedigree matters when your sense of self is shattered early on. Ultimately, Halaby acknowledges her place as an insider/outsider in American race relations. “The assumption I was white,” she writes, “allowed me privileges I am still unpacking.”

In reading The Weight of Ghosts, I occasionally found myself wishing to learn more about the effects of racism on Raad and his younger brother. This omission, in a work that is highly successful at bringing together various themes of loss and is delivered with largehearted and vulnerable honesty, might be a way for Halaby to protect Raad, even after his death. At any rate, it is heartbreakingly poignant when, at the end of the memoir, Raad speaks for himself. Halaby reproduces an article he wrote for the Daily Wildcat, a student newspaper at the University of Arizona, which he was attending. We come face to face with a brilliant young man who cared deeply about the world he lived in, and we lament his early passing.

Halaby must live in a world without Raad that continually reminds her of him:

The red toaster makes me think of you.

Falling asleep in front of a movie makes me think of you.

Chris in Gentefied makes me think of you.

Christian Cooper makes me think of you.

Al Pacino always makes me think of you. That moment we saw

him with Houri in Santa Monica when you were a baby was when

you caught the movie bug.

Looking at your posters makes me think of you.

Walking by the back door makes me think of you.

I am still waiting for you to walk in.

In one of her writing classes, Halaby instructs her students to record whatever they hear and see, including a staged disturbance she does not warn them about in advance. It is an exercise in paying close attention even amid disruption and chaos. The Weight of Ghosts is a hauntingly beautiful memoir, painstakingly attentive to the eddies of grief and the signs of regeneration, and a testament to the power of language to reconnect us with what we have lost.