In which the author argues that Meta adopts the censorious positions it does against free speech for Palestine because it is a dominant corporate platform, which requires it to take US hegemonic positions, especially support for Israel, for granted.

Omar Zahzah

The Palestinian American poet Naomi Shihab Nye’s 2019 collection The Tiny Journalist offers an extended treatment of social media’s influence on the Palestinian struggle. Inspired by the Palestinian journalist and activist Janna Jihad (the titular “tiny journalist”), who at age 12 became the world’s youngest journalist broadcasting the violence of Israel’s colonial military occupation to the world, Shihab Nye’s words are filled with references to the internet and social media, particularly Facebook, the primary mechanism through which the poet came to know Jihad’s work. “It is important to clarify that these poems or sections thereof are not Janna’s actual words,” Shihab Nye writes in her Author’s Note. “They are ‘my’ words, imagining Janna’s circumstances via her Facebook postings and my own personal and collective knowledge of the situation she was born into and lives with on a daily basis.”

The poem “Facebook Notes” is an imaginative synthesis of public comments on Jihad’s Facebook page: “Many say to Janna, Take Care of Yourself./We are praying for you. Janna, you are so brave… Others say you are too young to do this on your own.” The “About the Author” section of Tiny Journalist notes “Naomi Shihab Nye joined Facebook to follow Janna. She wishes American politicians would ‘follow’ Janna so they might be better aware of how their money is spent.” Shihab Nye’s poem about Palestinian poet Dareen Tatour, who in 2018 was arrested by Israeli authorities for publishing a poem entitled “Resist, My People, Resist Them” on Facebook, highlights the hypocrisy of a regime that jails poets for “incitement” and “terrorism” while systematically enacting brutal violence against Palestinians: “You beat us with butts of guns/for years,/tear gas our grandmas,/and you can’t take/Resist?”

In drawing on Tatour’s case and echoing the literal language of her poem, Shihab Nye’s piece reflects how social media is utilized by the Israeli state in its colonial abrogation of Palestinian rights. The collection thus reveals a somewhat paradoxical assessment of digital platforms: on the one hand, as an instrument of global illumination, and on the other, a tool of colonial suppression.

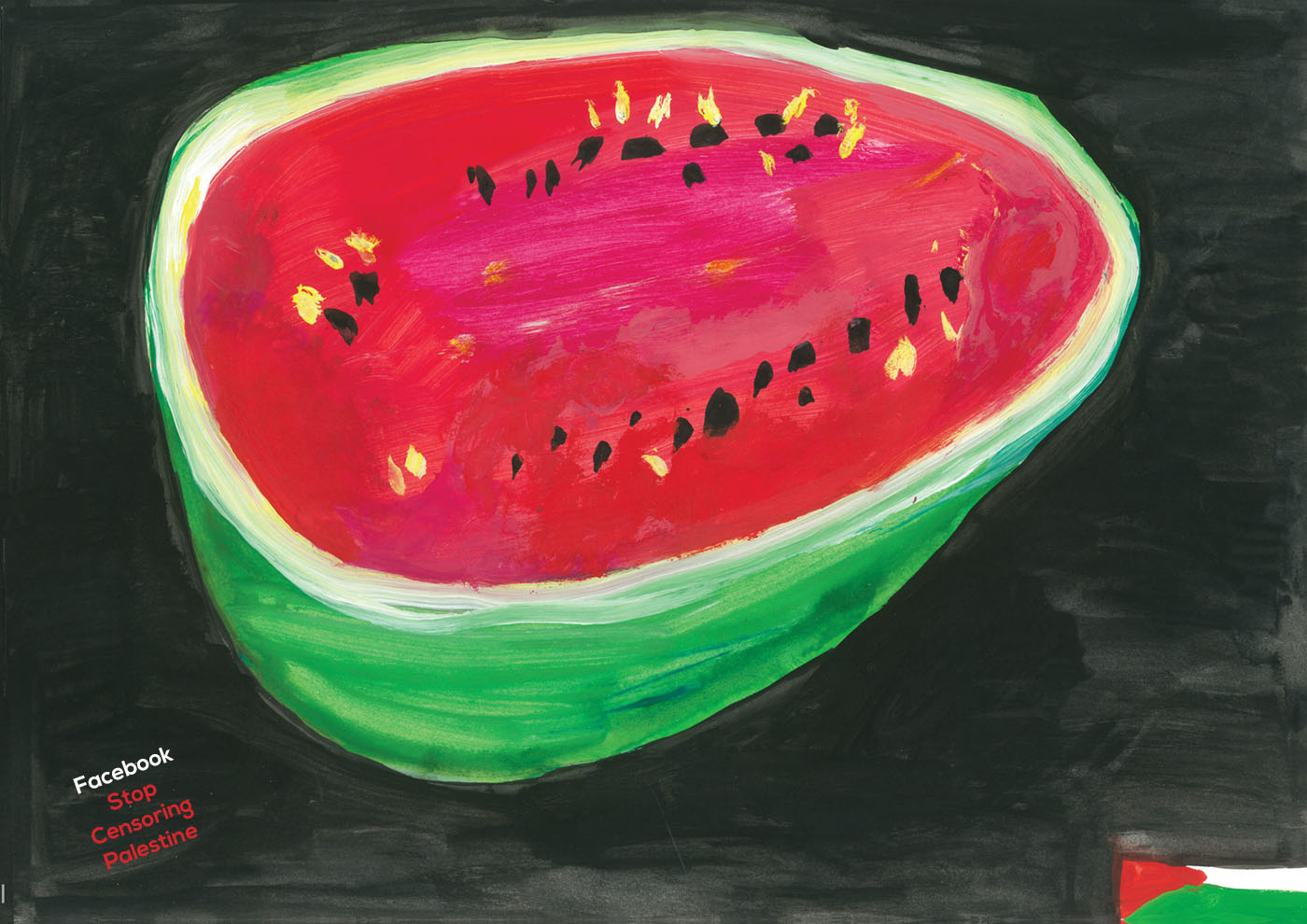

Our current moment has seen the social media juggernaut Facebook, now rebranded to Meta, lean ever more comfortably into the latter role. Firstly, there is the harrowing possibility that Israel is relying on metadata vulnerabilities in the Meta-owned messaging app, WhatsApp, to generate kill-lists of Palestinians in Gaza. Then, there is Meta’s longstanding policy of Palestine-focused censorship. As Sam Biddle reported in The Intercept, this policy apparently extends to Meta workers who describe a corporate environment that is unresponsive and even dismissive of their concerns. A July 11th, 2024 open letter by the recently-formed group Metamates4Ceasefire describes months of silencing against worker opposition to Meta’s policies regarding Palestine due to the company’s Community Engagement Expectations (CEE.) In addition to issuing a public statement calling for an “immediate, permanent ceasefire” in Gaza, the letter’s demands include “an end to censorship — stop deleting employee’s words internally in order to foster an inclusive environment where all communities feel seen, heard, and safe.”

Of course, Meta’s censorship is also external. By December 2023, Meta’s silencing of Palestinians was so flagrant that Human Rights Watch dedicated an entire report to it entitled “Meta’s Broken Promises.” Packed with a surfeit of examples and explicitly building on the work of digital rights organizations 7amleh, the Arab Center for the Advancement of Social Media, and Access Now, the report found “the censorship of content related to Palestine on Instagram and Facebook is systemic and global.” According to the report, Meta practices six primary means of anti-Palestinian censorship (each recurring at least 100 times:)

1) removal of posts, stories, and comments; 2) suspension or permanent disabling of accounts; 3) restrictions on the ability to engage with content—such as liking, commenting, sharing, and reposting on stories—for a specific period, ranging from 24 hours to three months; 4) restrictions on the ability to follow or tag other accounts; 5) restrictions on the use of certain features, such as Instagram/Facebook Live, monetization, and recommendation of accounts to non-followers; and 6) “shadow banning,” the significant decrease in the visibility of an individual’s posts, stories, or account, without notification, due to a reduction in the distribution or reach of content or disabling of searches for accounts.

With such a damning indictment, one would assume Meta would attempt to save face by denying these charges, if not substantively reversing course on its censorship of Palestinians. But no. Following extensive concern from rights organizations and activists about a long-anticipated prohibition on critical usage of “Zionist,” as of July 9th, 2024, Meta officially implemented a direct and explicit policy for this prohibition. Published on a page of its website entitled “Update from the Policy Forum on our approach to ‘Zionist’ as a proxy for hate speech,” Meta’s current guidelines enumerate the different conditions under which the company would presently ban anti-Zionist expression.

Facebook was criticized for appointing Emi Palmor, former General Director of the Israeli Ministry of Justice, to the Oversight Board. In 2015, during Palmor’s tenure, the Ministry of Justice established the Cyber Crimes Unit, which streamlined a pattern of successfully petitioning social media platforms such as Facebook to restrict Palestinian expression on their platforms.

Digital Gatekeeper

Project Censored‘s Andy Lee Roth argues that Big Tech companies such Google and Facebook/Meta, which exercise vast and generally unchecked control over public access to information, act as “new gatekeepers” of journalism by filtering and limiting public access to news stories on their platforms. Roth notes that these restrictions largely occur vis-à-vis algorithmic censorship, with media-worthy instances of human censorship, such as the 2020 decisions to restrict the accounts of Donald Trump and host Parler occurring with less frequency.

What makes Meta’s “Product Policy Forum Update” on its censorship policy regarding use of the term “Zionist” unique in this current moment of corporate digital hegemony is that it was explicitly resolved through meetings of the individuals who constitute the Meta Policy Forum, the body tasked with settling on the company’s so-called “Community Standards.” On an older page of its website on Facebook moderation policies, Meta clarifies that these Standards are “a living set of guidelines” that “must keep pace with changes happening in the world.” Meta’s touted reliance on collective bodies to determine policies, including its Oversight Board — a body separate from the Policy Forum which allegedly allows individual users to challenge company policy through appeal — is no doubt intended to give the corporation a democratic veneer even as it formalizes its vast power and entitlement to restrict global expression. (The Policy Forum Update notes that Meta will punt the question of whether it will be permissible to use the phrase “Zionists are war criminals” to the Oversight Board.)

In 2020, Facebook was criticized for appointing Emi Palmor, former General Director of the Israeli Ministry of Justice, to the Oversight Board. In 2015, during Palmor’s tenure, the Ministry of Justice established the Cyber Crimes Unit, which streamlined a pattern of successfully petitioning social media platforms such as Facebook to restrict Palestinian expression on their platforms. As 7amleh writes of the increasing (and increasingly successful) petitions by the Cyber Unit for social media corporations to censor Palestinians,

These are not isolated attempts to restrict Palestinian digital rights and freedom of expression online. Instead, they fall within the context of a widespread and systematic attempt by the Israeli government, particularly through the Cyber Unit formerly headed by Emi Palmor, to silence Palestinians, to remove social media content critical of Israeli policies and practices and to smear and delegitmize human rights defenders, activists and organizations seeking to challenge Israeli rights abuses against the Palestinian people.

To be sure, the Oversight Board can make decisions that contravene restrictions, as when it voted on July 2, 2024 to reverse a platform ban on the terms “martyr/shaheed.” But as noted in “Meta’s Broken Promises,” the fact that some pro-Palestinian messaging is left intact does not mitigate clear and evident patterns of systematic censorship.

Given Meta’s years of documented repression of Palestinian expression despite regular opposition, the July 9th Product Policy Forum write-up regarding critical use of “Zionist” on Meta platforms is not an “Update” so much as a confirmation. I argue that in issuing this decision, Meta has formally enshrined itself in the position it had only slightly less informally occupied for years now: as a powerful and partisan digital gatekeeper of Palestinian expression. That the corporation should move to further normalize the integrity of Zionism on its platforms in the ninth month of the Zionist state’s horrific genocide of Palestinians in Gaza is chilling, even callous, but also demonstrates the vital stakes of something as seemingly innocuous as platform access.

Broader Crackdown

Meta’s decision should also be viewed in relation to the broader crackdown on Palestine-related speech and activism at institutions such as universities — a tendency that has been decried as “authoritarian rot.” The “Policy Forum Update” rides on a broader wave of cross-institutional repression, with universities such as New York University (NYU) heavily restricting anti-Zionist speech and Palestine protests through mealy-mouthed student conduct policies. The heavy policing if not outright ban on Palestine expression operates in tandem with falsely rebranding a settler-colonial ideology (Zionism) as integral to ethno-religious identity. Meta’s decision thus further ensures that individual Meta accounts will largely uphold the political censorship of places such as universities — places that, as with social media platforms, are often branded as proponents of freedom of expression.

First day of classes at Columbia University pic.twitter.com/Vo8gICC8l9

— Nancy Kricorian (@nancykric) September 3, 2024

Meta’s “Policy Forum Update” on Zionism needs to be read in relation to the longstanding efforts of Zionist institutions to criminalize anti-Zionist speech by falsely equating it with antisemitism. As the Civil Rights organization Palestine Legal writes in a historical and legal overview of the origins of the repressive International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, or IHRA Definition of Antisemitism (which falsely equates criticism of Israel with antisemitism), “One of the primary tactics opponents of the movement for Palestinian freedom have used to silence political debate is the branding of all support for Palestinian rights as anti-Jewish.” Initiatives such as the IHRA definition weaponize the false conflation of antisemitism and anti-Zionism (or even general advo cacy for Palestinians) so as to assure the unquestioned impunity of Israeli colonial policies. Meta’s “Policy Forum Update” advances this repressive agenda at various points through strategic ambiguity and taking Zionist rhetoric for granted.

The PFU explicitly builds on the two conditions under which Meta professes to have already censored use of the term Zionist: “(1) where Zionists are compared to rats, reflecting known antisemitic imagery, and (2) where context makes clear that “Zionist” means “Jew” or “Israeli” (e.g., “Today the Jews celebrate Passover. I hate those Zionists.”) “Going forward,” Meta notes that it will “remove content attacking “Zionists” when it is not explicitly about the political movement” and adds the following, additional criteria for post removal based on the Policy Forum’s recommendations:

- Claims about running the world or controlling the media;

- Dehumanizing comparisons, such as comparisons to pigs, filth, or vermin;

- Calls for physical harm;

- Denials of existence;

- Mocking for having a disease.

Although the word “context” in the phrase “where context makes clear” in the second, premier criterion does a good deal of heavy lifting, the conditions for potential removal are alarmingly vague in a moment in which Zionist organizations such as the repressive Anti-Defamation League (ADL) directly equate anti-Zionism with antisemitism, and advocate accordingly. Nevertheless, even with varying political orientations, organizations such as the International Jewish Anti-Zionist Network (IJAN,) Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP) and individuals such as Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders reject the conflation of criticism of Israel and Zionism with antisemitism–a conflation ultimately meant to militate against understanding Zionism “from the standpoint of its victims” (the Palestinians) as Edward Said once described it. Simply put, “context” is by no means a universal given; it is an actively contested site, and with Meta’s current track record, there is little reason to expect a content-moderation policy more amenable to a political position that understands Zionism to be a vicious and violent settler-colonial enterprise. Furthermore, this constant need to “prove” that anti-Zionist advocacy for Palestinian liberation is authentically (not to mention sufficiently) opposed to antisemitism flies in the face of the actual history of the Palestinian liberation struggle, with movement leaders and intellectuals such as Fayez Sayegh clearly distinguishing between Zionism as a unique European settler-colonial enterprise and Jewish identity as such. It is the Zionist colonial project, now realizing its broader aspirations and capabilities through genocide, that requires a complete conflation between Jewish identity and Zionism in order to inoculate itself from criticism and opposition.

“Claims about controlling the media” is also less straightforward than it might seem at first glance. While it is true that the literal notion of Jews controlling the media is an antisemitic trope, US corporate media is an instrument used to manufacture consent for imperial policy (including Israel’s current genocide). It is important to note that, in Herman and Chomsky’s original formulation, the media’s manufacture of consent is not simply meant to imply a literal process of top-down political control; it refers, rather, to an elaborate system of ideological filtration that works so effectively that individual journalists and media workers can genuinely presume to be making objective decisions about coverage even as they are ultimately serving elite interests. Reflecting on the Al Aqsa Intifada, Edward Said observed that no foreign government had utilized US media as effectively as Israel’s in order to help construct a flattened and dehumanized perception of Palestinians/Arabs that worked in contrast to a more complex image of Israelis. Through various measures including training of college students to better advocate for Israel and lunches and free trips for journalists and politicians, Said writes, Zionist organizations have exerted a powerful influence on US media representations of Israel: “Never have the media been so influential in determining the course of a war as with the Al-Aqsa Intifada which, as far as the Western media is concerned, has essentially become a battle over images and ideas.”

Of course, Israel’s success in this regard is made possible by the cultural dimension of a political climate in which support for the Israeli state promotes the interests of US imperialism. The relationship between the US and Israeli settler-colonial states is thus not top-down so much as symbiotic. Nevertheless, with Zionism a clear pillar of US imperialism, it is not inaccurate to claim that corporate media is shaped by Zionist interests, as it is conditioned by larger imperial designs. Even as social media is functionally capable of serving (and often touted to serve as) an alternative to corporate media, there is little in the way of Meta’s conduct with regard to Palestine-focused messaging to assume that the company’s content moderation would subtend this political distinction.

Then, we come to “denials of existence.”

Despite the updated, collective wording which implies an association with groups, this is clearly an adaptation of the concept of “Israel’s right to exist.” The issue here is not simply that Israel has no inherent “right to exist.” It is that the very phrase itself, as argued by John Patrick Leary, is little more than a rhetorical trap: “Israel is the only nation with a “right to exist,” as the phrase is not commonly attached to any other country,” Leary writes. “And that’s the tell: This is not a legal concept, but a political one, available for broad interpretation and rhetorical weaponization.” As Leary explains, the “realest meaning” of Israel’s so-called “right to exist” is as a “flexible piece of political rhetoric” that often presumes Palestinian/Arab intransigence and whose shifting goalposts leave no room to question just how the colonial Israeli state is supposed to have a “right” to exist — i.e., at the direct expense of Palestinians.

Meta’s vague usage of “denials of existence” seems to further entrench acceptance of Israel’s so-called “right to exist” as a precondition of platform usage by translating challenges to this flawed imperative as impugning the rights of Jewish people as a whole. And yet, not only is it “both insidious and unethical to conflate Jewish people (of any national origin) with the existence of a violent, rapacious polity,” as Palestinian writer and professor Steven Salaita notes in his own reflections on fielding the question of supporting Israel’s “right to exist” — it is also that Palestinians, as the subjugated, colonized and yet resisting Indigenous population, have no obligation to legitimize the settler-colonial entity that continues to engineer their dispossession and death. As Salaita argues, “when Zionists demand that you affirm Israel’s right to exist, what they really seek is affirmation of Palestinian nonexistence.” It is not up to Meta to normalize Palestinian oppression, or dictate how Palestinians should relate to their colonizer.

Current Impacts

As Omar Ahmed writes for Middle East Monitor, following its rollout of the Policy Forum update:

Meta has already been involved in recent controversies, including an incident where the company was compelled to apologise to the Malaysian prime minister after removing his post offering condolences for Hamas’s late political leader, Ismail Haniyeh, which Meta later claimed was due to “an operational error.” Additionally, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has criticised what he describes as “digital fascism” [for Meta’s apparent censorship of condolence posts for Haniyeh] after the country blocked access to Instagram.

Most alarmingly — and in a disturbing demonstration of how Meta’s “Community Standards” act as an instrument of gatekeeping — Ahmed notes that, on August 16, 2024, Meta permanently banned the news outlet The Cradle from Instagram and Facebook for “Community Standards” violations. “The site’s critical coverage of Israel’s actions in contrast to its favourable reporting of the region’s Resistance Axis likely made it a clear target for Meta’s policy updates,” Ahmed writes. Ahmed quotes Cradle columnist Sharmine Narwani’s observations that Meta’s censorship seems primarily concerned with English language postings: “They’re very concerned, these large platforms and the governments, that their own constituents will hear facts about what’s happening in the region.”

Why would Meta continue on the path of restricting anti-Zionist and pro-Palestine speech on its platforms, with these updates from the policy forum being only the latest example?

Omar Ahmed suggests that one reason has to do with the efforts of CyberWell, a Tel Aviv based non-profit with Israeli and military intelligence officer founders that has lobbied social media companies such as Meta, TikTok, and X to take action against what it terms “online antisemitism.” An investigative report by Lee Fang and Jack Poulson linked in Ahmed’s article shows the organization claiming victory over Meta’s July 9th Policy Forum Update, writing in a press release: “CyberWell intends to leverage its technological tools and analysis efforts to ensure this policy is implemented efficiently and fully, and that Meta’s moderation tools are trained to effectively bar this content.” Fang and Poulson observe that CyberWell board member Adam Milstein also took credit for CyberWell for Meta’s policy Updates in a series of posts on X. (As reported by Alex Kane, Milstein, who secretly funded the campaign of Zionist candidates for UCLA student office in 2014 by disguising these covert funds as donations to the campus branch of Hillel, also sits on the board of the Israel on Campus Coalition (ICC), an organization with ties to the Israeli government that launches various online attacks against pro-Palestine organizations, including through SJPUncovered, an account dedicated to harassing and defaming members of Students for Justice in Palestine (SJP.) In 2018, Milstein was named as a funder behind another infamous anti-Palestinian online blacklist site, Canary Mission, in a censored documentary by Al-Jazeera.)

There is no reason to doubt that Cyberwell, which also continues to advocate for social media companies to implement the aforementioned IHRA definition of antisemitism, could have had some impact on Meta stakeholders. Several high-profile Meta affiliates also have various investments in Israel. As reported by Paul Biggar, founder and CEO Mark Zuckerberg and former COO and current Meta board member Sheryl Sandberg boost Israel’s October 7th atrocity propaganda—Zuckerberg donated $125K to ZAKA, the organization that spread the “mass rape” hoax as well as the beheaded babies lie parroted by various media outlets, while Sandberg went on tour to spread the same propaganda—while Meta’s “most senior policy decision maker,” Mark Rosen, is an Israeli who lives in Tel Aviv and was formerly a member of Israel’s infamous Unit 8200.

Digital/Settler-Colonialism

But even given such considerable pressure from various directions, it’s important to look beyond lobbying and individual influence alone. For some time, I have been elaborating a concept I refer to as digital/settler-colonialism, which is meant to capture how the colonial tendencies and practices of US Big Tech converge with the Israeli settler-colonial project. The US corporate media is an illustrative complement to this discussion, for even while there is and has been extensive Zionist pressure and lobbying for US corporate media to promote Israel and Zionism, US corporate media is receptive to this pressure precisely because acceding to such pressure is already in the ultimate interests of US geo-imperial policy.

As argued by Afonso Albuquerque, US cultural imperialism is best understood as the twinned operations of media imperialism and intellectual imperialism working in tandem to promote a neoliberal world order most in line with US political and economic interests. When we recall that it is most correctly understood as a mouthpiece for imperial policy, we can more clearly see how normalizing support for Zionism, the ideology of a proxy state whose “qualitative military edge” and intransigence to international codes of conduct benefits the designs of Western global hegemons is in clear keeping with the political function of US corporate media. Thus, even as Zionist groups exert considerable pressure upon establishment media, we should understand that media receptivity to this pressure is facilitated by US imperialist policy, which includes support for Israel and mobilizes the media as the cultural arm of its broader operations.

Support for Zionism is a hegemonic position. As such, it exceeds individual choice or preference. While personal connections to Israel on the part of Meta top brass might help explain the degree to which Meta is willing to adopt pro-Israel censorship policies, it is highly unlikely that a social media company could become as dominant in the national and global spheres as Meta without adhering to US establishment politics — including support for Israel. We do not have, as social media overlords might want for us to believe, a choice between corporate legacy media and “disruptive” social media. What we have is a false choice between corporate legacy media and, to borrow a phrase from Vincent Bevins, corporate social media (i.e., companies such as Meta.) Even as one might presume that providing for more political plurality would better meet Meta’s goal of maximizing user engagement, the reality is that, just as corporate legacy media is a core institution in the functioning a global imperialist capitalist system cohered through US hegemony (with support for Israel a crucial lynchpin of this policy,) corporate social media is structurally de-incentivized from opposing the machinations of US imperialism and empire. As the superrich continue to center their stranglehold on public expression through dominance of hegemonic digital platforms, we will likely continue to be reminded of all of the ways in which “disruption” was never anything more than a myth meant to garner more clicks and scrolls.

The additional prohibitions on anti-Zionist speech posed by the Policy Forum Update only further make Meta’s “Community Standards” a tool of digital/settler-colonialism, furthering the Israeli settler-colonial project by eroding platform-based anti-Zionist and pro-Palestine speech. Of course, the very notion of “community standards” is a misnomer, as it is the powerful, not the public, that establishes these conditions. As Allison Butler writes in Justice Rising, the Publication of the Alliance for Democracy, Vol 7, no. 4, Fall 2024:

The government of social media is one run by tech oligarchs where supreme power is vested in the executives and exercised by them directly or indirectly through a system of complex and complicated privacy policies, terms of service, and creative use of language. It is the platform operators, not the community, who set the community guidelines.

Challenging digital/settler-colonialism is part and parcel of the broader project of fighting against an imperialist and hegemonic order that incentivizes the oppression, exploitation, and genocide of the subjugated and suppresses anti-oppressive dissent. Therefore, it is imperative to defy the gatekeeping of powerful corporations like Meta by continuing to advance the project of Palestinian liberation on as many platforms as possible, thereby rejecting colonial and corporate conceptions of “community standards” once and for all.

Very well articulated.