The author Fida Jiryis is presenting her book at a launch at the Qattan Foundation, 27 An-Nahda Women Association Street Al-Tira, Ramallah, Palestine, on Nov. 29, 18:00 local time. She will be in discussion with Haifa-based lawyer Diana Buttu and Dr. Ehab Bessaiso, a Palestinian academic.

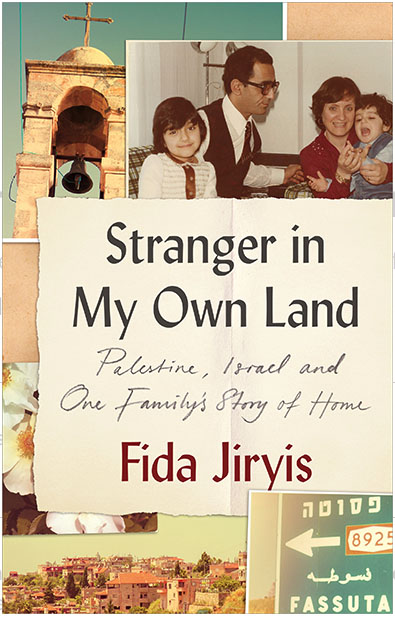

Stranger in My Own Land: Palestine, Israel and One Family’s Story of Home, by Fida Jiryis

Hurst Publishers 2022

ISBN 9781787387812

Diana Buttu

How does return to Palestine following exile feel? What is it like to return to a place that one has heard so much about but that, in reality, bears no resemblance to the stories due to decades of colonization? How does one “fit in” after a lifetime of being away? These are but a few of the questions author Fida Jiryis asks in Stranger in My Own Land: Palestine, Israel and One Family’s Story of Home.

To answer them, Jiryis takes us on a personal, unique and often tragic family journey. She and her family were one among only a few Palestinian families permitted to return to historic Palestine following the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993.

The book, part biographical and part autobiographical, begins with her father, grandparents and great grandparents experiencing the Nakba in 1948, and escaping the ethnic cleansing that Jewish forces and the nascent Israeli polity visited upon hundreds of Palestinian towns and villages. Her father, Sabri Jiryis, 10 years old at the time, lived in the northern Palestinian village of Fassouta. As Palestinians from neighboring villages fled or were expelled, Sabri bore witness to his grandparents’ attempts to provide them with food and water for their journey into exile.

Unlike three quarters of the Palestinian population, which fled or was expelled to neighboring countries, the Jiryis family remained in Palestine. Yet, along with the others who stayed in what had become a Jewish state, they were transformed overnight into unwanted people in their own homeland. These experiences left an indelible impression on Sabri, his parents and grandparents, marking the beginning of what would soon become his lifelong dedication to the plight of Palestine and the Palestinians.

Jiryis evocatively describes the early years of her father’s life under Israeli military rule, the Jewish state’s system for tracking and controlling those Palestinians who had remained in their homeland and, despite being granted Israeli citizenship, were severely discriminated against. During that period, which lasted from 1948 until 1966, Sabri attended school in Nazareth and later was accepted at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem to study law. He was one among a handful of Palestinian students at the university at the time.

As the years passed, Sabri and his friends more deeply registered the full impact of Israel’s military rule: the requirements to obtain permits from the Israeli authorities for all manner of travel, including from one village or town to another; the stitching together of labyrinthine laws to justify and obfuscate Israel’s theft of Palestinians’ land; and, of course, the multitude of methods the Jewish state devised to stifle and contain Palestinian efforts to organize against its actions. It was during this period, in 1958, that Sabri and his friends established Al-Ard (The Land), a movement to advocate for the rights of Palestinians, and attempted without success to register it as a political party. Stranger in My Own Land masterfully chronicles the backstory to these historic events and the attempts by lawyers to secure even the most basic rights under Israel’s legal system.

Because of their work, Sabri and many of his friends frequently were banished from their towns, forced to reside in different locales and to check in daily with various police stations. Israel scrupulously monitored their every move, endeavoring to block them from organizing. It outlawed Al-Ard in 1964.

Ultimately recognizing the futility of using the Israeli system to challenge Israeli actions, and subject to increasing harassment and persecution in Israel, Sabri (and his brother Geris) decided to leave the country. By this time, Sabri had married Hanneh, also from Fassouta; they left together in 1970. Sabri and Hanneh eventually ended up in Beirut, Lebanon, where Jiryis and her younger brother were born, and where the family began their new life in exile, a mere 100 kilometers north of their native Fassouta.

In the years following his move to Beirut, Sabri’s pioneering book on Israel’s Palestinian Arab minority, The Arabs in Israel, the original Hebrew version of which was heavily censored in Israel, appeared unexpurgated (and updated) in Arabic and English. He also joined and later became director of the Palestine Research Center, which had been established in 1965 to publish material on Palestine, including the journal Shu’un Falastiniyya. It was during this period that Jiryis, still a young child, experienced the Lebanese Civil War, which erupted in 1975, and Israel’s invasion of Lebanon, which took place in 1982. For Jiryis, the invasion had a particularly traumatic effect; in 1983, Israel, using a Lebanese proxy group, bombed the Palestine Research Center, killing her mother Hanneh, who was working there, and many others besides.

“It took several days for my father to be able to tell us,” recalls Jiryis, referring to herself and her younger brother, Mousa. “When he finally broke the news, in his and Mum’s room, we stared at him in silence. Mousa’s little voice broke: ‘What does that mean?’”

Their father’s face was “contorted in pain” as he answered his son, “‘It means she’s gone and we’ll take care of each other.’”

Ultimately, the stricken Jiryis family left war-torn Lebanon for Cyprus. Several years later, with the signing of the Oslo Accords, they finally returned to Palestine. Jiryis herself was 22 years old and had never visited her homeland. Owing to the fact that her father had held Israeli citizenship before his departure into exile, she was able to acquire the same and to establish residence in historic Palestine. For the next several years, Jiryis struggled with adapting to her immensely transformed homeland, while witnessing the extent to which Israel effectively had erased Palestinians. On a daily basis, she encountered racism in her interactions with Israelis and was left wondering about, and questioning, the coping mechanisms used by Palestinians who hold Israeli citizenship or a Jerusalem identification card (together, just over 20 percent of the state’s population).

The admittedly minor critiques one might summon for this carefully considered, thoughtful and moving book concern Jiryis’s description of her family’s process of fitting in when they return to Palestine. While she elaborates on her own struggles, she omits description of how her father coped with his return. A reader cannot but yearn to glean more about how her father and uncle react and adapt after their quarter century in exile. Additionally, the book swiftly jumps from 2015 to 2022. One intuits that Jiryis sought to conclude the book with current events, but it is unclear why this seven-year period is skipped over.

To be clear, Stranger in My Own Land, the product of years of detailed and diligent work, is both commendable and the sort of book one hopes others will emulate. Jiryis lovingly, meticulously and affectingly relates the story of her own family and their specific experiences, yet these experiences can so easily be translated to virtually all Palestinians, whether in historic Palestine or in the diaspora. Jiryis herself bears witness to the damage Israel has done to the Palestinian territory known as the West Bank, which it captured from Jordan in 1967 Arab-Israeli War and has since subjected to military rule, and where the author has taken up residence. In theory, parts of the West Bank are ruled by the Palestinian Authority, a Palestinian governing body, but even in these areas the reality is quite grim. As Jiryis observes:

Working with the public, private and civil sectors, I began to see how deeply the Israeli occupation damaged our economy. Universities were mostly restricted to students from their own localities due to the movement restrictions. Private sector companies could not grow at will; their imports, exports and manufacturing facilities were limited by Israeli constraints. Tens of thousands of Palestinian laborers were pushed to work in Israel, earn less than Israelis and having no social benefits. The public projects I worked on showed the humiliating controls that the Authority was under. The “interim” situation that had followed the Oslo Accords had become the status quo, with no Palestinian state in sight.

Indeed, Israel’s colonial rule, which has disfigured our country, our language, our culture and our region, has rendered all Palestinians strangers, even those of us living in our own land.

![Ali Cherri’s show at Marseille’s [mac] Is Watching You](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/Ali-Cherri-22Les-Veilleurs22-at-the-mac-Musee-dart-contemporain-de-Marseille-photo-Gregoire-Edouard-Ville-de-Marseille-300x200.jpg)

![Fady Joudah’s <em>[…]</em> Dares Us to Listen to Palestinian Words—and Silences](https://themarkaz.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/SAMAH-SHIHADI-DAIR-AL-QASSI-charcoal-on-paper-100x60-cm-2023-courtesy-Tabari-Artspace-300x180.jpg)