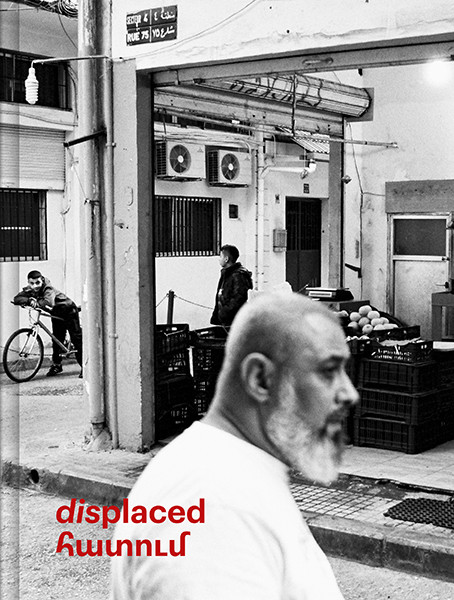

displaced հատում, photography by Ara Oshagan,

with an essay by Krikor Beledian

ISBN 9783969000144

Kehrer Verlag 2021

Karén Jallatyan

Diasporic In/visibilities

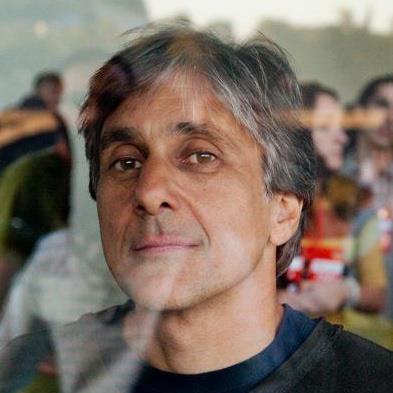

There are few works in English that capture the texture of diasporic Armenian experience in the enchanting richness of its ghostly creativity. This is what makes the recent publication of displaced հատում remarkable. It offers photographs by the Los Angeles-based artist Ara Oshagan and an essay in Western Armenian — “The Bridge” — by the Paris-based writer Krikor Beledian, along with an English translation by Taline Voskeritchian and Christopher Millis. The primary — in a naïve sense — locale evoked by this volume is Beirut, particularly its Armenian quarters, which both artists knew as children. Both left Beirut in their youth — Beledian in the ‘60s, Oshagan in the ‘70s — before and because of the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990), but have sustained creative ties with their birthplace across decades.

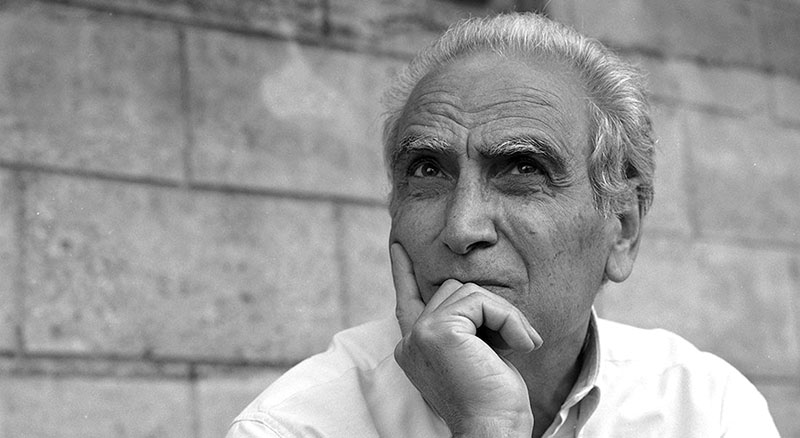

To state that Beledian is one of the most sophisticated and prolific writers in the Western Armenian idiom is to make the reader in English experience very little. Beledian’s invisibility as a major writer is part of the fate and struggle of Western Armenian — a literary language that after an accelerating period of gestation in the 19th century, emerged in a discernibly national form at the beginning of the 20th in the Ottoman Empire, especially Constantinople, to be forever cut from its milieu by the 1915 Armenian Catastrophe; a literary language that since then and for generations has been surviving in Paris, Beirut, Aleppo, Boston, Los Angeles, Sydney and elsewhere under diasporic conditions, without the usual nation-state-driven administrative and educational infrastructural support to shape its future. Western Armenian’s invisibility — literally and literarily — is partially assuaged by this bilingual publication of Beledian’s “The Bridge ” (Կամուրջը, Gamoorj’) in Europe and now in the US.

A restrained figurative openness — a relentless experimenter of literary form that Beledian is — gives “The Bridge” a rare evocative power. A bridge is referenced early in the essay as connecting The Hill neighborhood of Beirut, where Beledian was born and grew up, and the set of quarters that bear names from the erstwhile Armenian region of Giligia, the bridge being the “official gate” to these neighborhoods down The Hill. Beledian writes about how as a child he, with family and peers, would visit these neighborhoods during summer and fall not by taking the bridge but by walking under it, through the riverbed when the water was low. Regarding this “alternate route,” Beledian notes:

This passage neither delineates a path, nor can it really be regarded as a road. Every passerby who dares to plunge into the unknown departs from desired or possible places, does not stop, does not follow any precedent […] This is a temporary trajectory, where one who arrives has neither the chance nor the inclination to stop.

And when the river returns, this uncharted path is erased: “When the waters rise, very little that could have become a fixed point, that could have remained staked, nailed to the soil and inscribed in the shallows, can withstand the eddy’s force.” (11) The unofficial and temporary, erased and recurring, the secret and transgressive experience of crossing is what displaced հատում inscribes through Beledian’s essay and Oshagan’s photographs.

And yet, during winter and spring, when the river floods, the child recalls entering the Giligia neighborhoods through its “official gate,” the bridge: “In your imagination, the bridge seems durable, a constantly busy mass on which the trams, some idling and others sometimes speeding seemingly for a second suspended in mid-air, almost ethereal, prove the structure’s stability.” (13) The translators choose “ethereal” to render Beledian’s hand-picked word այերային (ayerayin) which denotes and declines air. The bridge grounds and is metaphoric, is at once real and ethereal. As a figure, it is even adequate for thinking about Voskeritchian and Millis’ translation of Beledian’s essay, which takes daring poetic leaps.

The world of the child is the lived experience of the cityscape, filled with ritual and stories, inhabited by and sustaining kin, friends and co-dwellers: “When you are a child and they bring you to these parts a couple of times a year only, you are almost enchanted by everything; often you forget your ability to resist such enchantment, your eyes focus on the present only.” (15) The child walking on the bridge is tempted to touch the toys for sale, not allowed to do so by his mother; passersby, who stop and fondle the merchandise, are also enchanted. (16) He encounters different Arabics spoken on the sidewalks of the bridge, passes by the butcher shop, remembers the men seated at a table on the sidewalk around drinks. As for the temporal shape of enchantment: “Oh, happy, simply because you had no sense of time.” (17)

Displaced: From Beirut to Los Angeles to Beirut by Ara Oshagan

Here, the translators render into idiomatic English what in Armenian has quite a jarring quality, which in a word for word translation could also be rendered in the following manner: “simply because time wasn’t.” (16) Then come memories of walking into the neighborhoods, encountering the facade of a newspaper building, the swearing, luscious shoemakers, movie theaters with signs bearing Armenian names but not offering movies in the Armenian language. (18) Beledian remarks ironically: “Cinema is the threshold to the other world, which is here, all around, but is not revealed. And whatever is not revealed does not exist, for sure.” (18) The otherworld approached and missed is a major theme in Beledian’s literature.

Giligia

What is this Giligia? It is the Western Armenian pronunciation of the medieval Armenian kingdom of Cilicia north of Lebanon, at the southern Mediterranean coast of Turkey, bordered by the Taurus mountains in the north. A kingdom known for its illustrated manuscripts and alliances with the Crusaders and the Mongols alike, destroyed by the Mamluks of Egypt in the end of the 14th century. An ersatz kingdom already, one of displaced origin, as it formed around the 11th century with the exodus and resettlement of Armenian nobility from the Armenian Highland. And the opening lines of Beledian’s essay: “Down from The Hill, beyond the river, is Giligia, as you call it. Nor Sis, Nor Adana, Nor Marash, Nor Amanos, Nor Tomarza, Nor Yozghat — you rattle them off in a single breath. Giligia lives again, right here — who knows until when? — in its legendary names.” (11) “Nor” is the Armenian word for new. When the river returns, it floods into these neighborhoods: “Theirs is a transient dwelling, always subject to expulsion or uprooting.” (13) One more reason for the inhabitants of The Hill to have a condescending attitude towards the dwellers below, even though the floods remind the former of their not so recent lacerating experience of mass exodus from their ancestral lands. (22)

Entering the neighborhoods of Giligia, the child, Beledian notes, walks into his checkered pre-catastrophic origins, since among its inhabitants are family relations and close friends of his parents who have survived the murderous mass exodus of the Armenians. A search for origins that is endlessly staged and thwarted in Beledian’s literature. And yet:

“But you all know that these surroundings will not last. The expenses, untended or cultivated, will be occupied, will be subdued by oppressive forces, will lose their strangeness. Factories, workshops, five- or six-story buildings will erase that old geography and human presence. The places will be turned to stone, will become smaller, will be spoiled. The war begins slowly, with the imperceptible pace of seemingly almost-invisible incidents, and then the clashes. But at the moment, there is no war.” (13)

Self-consciously situated at the interstices of the past and the future, “The Bridge” gives the 1950s environment of the child a dynamic visibility, one that is tied with thousand threads to the past and the future while emanating its singular otherworldly charm.

Paris — where Beledian settled as a university student and remained after his studies — also folds the spatio-temporal texture of his essay. Here, the child is standing on the bridge in Beirut:

“When your gaze returns to the path opened by the bridge, for a moment you feel as if you are swaying on the waters flowing from above in the sky and below you. And it’s that initial impression that will return to you, it seems, when you cross the Seine from Pont des Arts whose ethereal course makes for a difficult comparison with your bridge, although both glorify metal. The sensations of wavering, swinging, even oscillating, continue still, dizzying sensations that are, as it were, a musical prelude for the drama to come.” (17)

There is that word ethereal again, in relation to another bridge. The search for origins, for the “initial impression” is never crowned with success. The drama to come may also include the buildings that are going to be built next to each other in these neighborhoods. To gain a sense of this thickly layered landscape, it is also worth watching Joanne Nucho’s experimental documentary The Narrow Streets of Bourj Hammoud (2017). More broadly, the future oriented shape of Beledian’s essay speaks of the displacing variations of diasporic chronotopes.

Precise descriptions are interspersed with and are set next to four highly self-reflective incisions — another word and way to think of the significance of the Armenian part of the title հատում (hadoom) — that suspend the text. The first among such incisions: “To describe like this means losing a thousand and one details; there are, between what is noted, expanding interstices if not outright cracks — a surfeit of voice, and call, and scream; above all, the gray, cruel surface of such spaces. What ruins… At the outset, reconcile yourself to loss, like Giligia which is not there; more than anything, abandon any pretense of achieving more, any mastery, any completeness.” (15) Here, we can get a deeper sense of the figural openness that characterizes “The Bridge.” Through such incisions of heterogeneity Beledian’s text approaches loss, without reducing its experiential, remembered and linguistic effervescence into ready-made, easy-to-handle abstractions about absence.

The last of these suspensions addresses people and stories: “When people appear, narrative begins. Even if you push it out of your mind, it does not cease imposing itself. A city without narrative is no different from an abstract building. The more labyrinthine the story, the greater the need to give it shape. Mazes everywhere, of course. Especially when you don’t live their daily lives. You are an observant eye bringing everything into the depth of its image. Or you project onto this image the shadow world of memory.” (23) Shape of the city, shape of stories, especially for an outsider. Re-shaping, as an imperative of writing and a threat to indexical (originary) resting place, was already a concern in the second incision. It returns in the passage above in relation to the status of cities/stories with the last two sentences: are we reading the testimonial recording of an outsider’s childhood memories of a place with its people and stories or are the latter the result of an illusion generated by hollowed memories that bar any possibility of testifying? Beledian thus challenges the reader, while inaugurating with this incision the three narratives that constitute the latter half of the text. They are stories of transgression, constitutive of the secret world of the Giligia neighborhoods, having lasting consequences well beyond them.

Incised suspensions is what Oshagan’s black and white photographs do, some 59 of them in displaced հատում. Transgressive, intimate, ridiculous, out of focus and with curious framings, invoking and inviting absences, they struggle against photographic regimes that offer un-self-reflective sentimental and melancholic idealizations of culture. In a stroke of curatorial brilliance, the reader/viewer is invited to jump back and forth from Oshagan’s photographs to Beledian’s essay. The layeredness of Beirut can thus be gleaned through the photographs, which in turn enrich the detailed texture of the essay by giving it a visual aspect that is not merely imagined by the reader.

Oshagan’s versatility as a photographer is seen through the earlier volume Father Land Հայրենի Հող (powerHouse Books, 2010) dedicated to Artsakh/Nagorno-Karabakh (a disputed territory internationally recognized as Azerbajian) — an enclave historically inhabited by Armenians. Like the volume under review here, Father Land Հայրենի Հող (hayreni hogh) has an essay by a prominent diaspora Armenian writer, this time by Vahé Oshagan (1922-2000), the photographer’s father, and is available in an English translation by G.M. Goshgarian. Oshagan’s photographs in Father Land Հայրենի Հող approach the struggles that nationhood entails without falling prey to its usual sentimental ideological framings.

Only one panoramic shot of the cityscape is given in displaced հատում. Oshagan’s playful rebelliousness is inscribed in the way the shot is not quite symmetrical and has a hand protruding from the left, mid-air, mid-conversation, ethereal — the hand of a youth it seems — pointing with the index finger to the city. The indexicality of Beledian’s essay revisited: something happened there, is happening now, a story. A small cross hangs from the wrist of the person pointing, the bottom tip of which almost meets the top of what appears to be the highest building. The shape of a church is thus suggested: stories and cityscapes, infused with faith and ritual, forming exclusively through the photographic image. This displaced panoramic shot is one of the three (four, if we count the cover of the book, a photograph that reappears inside the volume) photographs that preface Beledian’s essay.

Numerous thematic and figural points of contact emerge between Oshagan’s photographs and Beledian’s essay. Images of closed cityscapes and interior spaces with people hardly noticing the camera abound. We are in the dense cityscape evoked as the future in Beledian’s essay. Mostly men hanging around on the sidewalks of streets, seated, standing, walking, talking. In one such photograph, a woman’s profile appears in the foreground, on “our” side of the sidewalk, walking by the men, while a romanticizing poster of what looks like an Armenian church and a panorama is hanging from the wall across. A contained and yet unpredictable lived experience is evoked through these photographs.

People in church, a close-up of a funeral procession, a view into a cemetery with Armenian inscriptions on a cross and bullet shots all around; a close up of an official list of handwritten names in the Armenian script, the partially legible title of the document referring to the Bourj Hammoud cemetery; hands going over the list, looking for those they have lost. In contrast, women and men dance in what appear to be private house celebrations. Somewhere outside, children play war with what, one hopes, are fake pistols.

Street scenes, some grotesque, some languid, all setting up some expectation or giving a piece of life. Merchants selling produce, animal meat hanging for sale; butchers cutting it in private. Transience invoked by a dog running and a motorcyclist driving through a narrow street. The hazy photograph of a child’s face from the side, Beledian’s dreamworld invoked. Lots of children, playing in schoolyards, running in the streets. A displaced and displacing photographic gaze thus emerges, chasing after life in its effervescence.