From time to time, TMR reviews recent titles published in other languages, to give readers insight before they become available in English.

A.J. Naddaff

One of the most common features of tragedy is that the events that will unfold on stage are summarized by either the chorus or a messenger at the start, foretold by prophecies and oracles. Something similar happens in Racha Mounaged’s La Blessure (The Wound), which starts roughly where it ends. It is as if an imaginary messenger — the omniscient narrator — has laid out the misfortune of Jad, the child protagonist: he is in a rehabilitation center for having stabbed a classmate with an oyster knife. His mother, the school’s cleaning woman, finds out one morning during her shift when she is called to the principal’s office. Then it backtracks. We know what is coming. Mounaged has set us up for the child’s collapse. But we fall for it with heavy hearts. This is the sensibility of a great story, not dissimilar from the late Egyptian writer Nawal El Sadaadwi’s Woman at Point Zero and her murderous protagonist Firdaus, who tells her life story in prison before her execution.

Jad’s life story is a chasm of tristesse. Set in wartime Lebanon, his suffering stems from the conflict of parental loyalty, or the inability to recover from the forced, mutually exclusive decision inflicted upon him by his parents’ brutal divorce. To choose his mother, and in turn, resent his father. It is as if the only way to find peace is to eliminate his father. “I am the owner of my thoughts… I want and will erase the image of dad.” But the decision leaves him in a state of turmoil. Jad wets his bed; he has nightmares; he is anti-social. He is unmoored from a social network of peers his age that could encourage him. Having removed the enormous potential of paternal love from his life, he suffers identity problems. Memories of his father, his family, under the sun, on a merry-go-round, at Beirut’s Rawda cafe, haunt him. The image of his father smiling, charming, floating in his mind, returns uninterrupted; at other times, we see a father reeking of sweat mixed with alcohol, a man full of false promises.

Jad’s perspective is told by an omniscient narrator, who interjects every so often to ask critical questions, for instance, “Was it so unreasonable that Jad missed his father?” There is a long tradition of novels told from child perspectives in modern French literature and Mounaged drew inspiration from Hervé Bazin’s Viper in the Fist, Yann Queffélec’s The Wedding, Agota Kristof’s The Notebook and Roman Gary’s The Life Before Us. Yet they are all bound in pulling the reader towards a shared innocence we all once possessed.

Jad is a neutral name. In France, girls carry it, and in Lebanon, it’s the opposite, perhaps a reflection of the novel’s universal pull, an exclamation to not underestimate children’s thoughts and feelings around the world. Jad’s wisdom rings similar to Saint-Exupéry’s legendary Little Prince, when the Little Prince says: “Grown-ups never understand anything by themselves, and it is exhausting for children to have to provide explanations over and over again.” Indeed, the grown ups in Jad’s life fail to understand that their adult disputes, whether political, sectarian, familial, have sidelined children, the upcoming generation. The results are disastrous. I’m reminded of the Lebanese novelist Rachid el Daif’s autobiography ألواح or Tiles, which some critics have read as a critique of parenting and the sanctification of motherhood in Arab culture. There is a kind of honesty we are not used to here. As El Daif himself recently told me, “There are germs that are preventing us from building a modern state, and we inherited these germs from our mother and fathers.” We were on a walk in the Koraytem neighborhood of Beirut and witnessed a teenager litter a Pepsi can and continue walking.

The Anguish of Being Lebanese: Interview with Author Racha Mounaged

It is not only the parent dispute that disturbs Jad. He is traumatized from the war raging around him. At one point, Jad witnesses a car bomb shake the premises. Lifeless bodies spread across the ground with brownish blood drying on the asphalt. His uncle teaches him how to distinguish between “the tense roar of a M16 and a Kalshnikov.” Interspersed in the horror are moments of rare joy. He dresses up in a skirt with a turquoise top and two large earrings at a surprise birthday for his mother while his favorite song by Ragheb Alama plays in the background. Hips and laughter and family envelop the scene. But war and family conflict are always present.

Jad’s mother is overwhelmed with events as a single mother paying bills, dealing with irksome lawyers for a divorce and raising two children. Jad’s only bonds are with Abu Ali, an enormous bronzed fisherman whose scraggly beard and face are worn by salt, and his daughter Jana, whose beautiful green eyes radiate under the sun. Thanks to Abu Ali, Jad learns how to fish, but even this joy is ephemeral. Abu Ali is expelled from his cabin overlooking the gigantic Raouché rock on Beirut’s corniche because he does not have a proper permit. Meanwhile, a giant hotel “El Magnifico” is illegally constructed alongside the sea, reflecting the savage privatization that characterized the reconstruction farce of the post-civil war nineties — the hopefulness for the future that would all come crumbling down.

Today, Lebanon is facing an enormous existential crisis as a result of its third exodus wave in the past century. The first was in the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century when mainly Christians fled from Mount Lebanon, then during the civil war (1975-1990) and now, in the wake of the Aug. 4 port explosion, renewed instances of sectarian violence and an economic meltdown that is one of the worst of the past 150 years. Just as Jad in the novel, for so many today, education is the only way out. School is the intact space where Jad can restore his health, well-sheltered. But even there he is not truly protected. A bully named Youssef of wicked humor and who sports the nicest clothes throws paper airplanes at him, and even calls Jad’s sister a whore. His only friend, Raphael, taciturnly observes as a passive bystander. All this can be ignored — temporarily — because of an international competition in Greece that Jad is determined to attend.

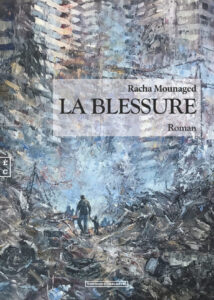

To distract himself, Jad immerses himself in books on ancient Greek history, the Parthenon, the temple Acropole, and key dates. But the conflicts are stronger than his indomitable will to succeed — his competition is cancelled as a result of a resurgence in sectarian fighting that shakes the country, the straw that breaks the camel’s back. The sensible and precocious Jad collapses into a raging fury and stabs his adversary Raphael, ironically with the weapon of the rich and privileged: an oyster knife. Unrecoverable class injustice married with the emotional trauma of his parent’s divorce results in the wound that he inflicts across his enemy. There is a glimmer of joy, of some sorts, in the end, which I will not disclose, found in a look that accepts Jad in his totality. We can infer this from the impressionistic title image, a painting by the British artist Tom Young, which features an adult who guides a child by hand out of the destruction and debris caused by the Beirut port explosion. “I like the side which accepts reality without denying it, but which proposes a cure through art,” the author said in a recenter interview. With all the pain that this riveting story carries, perhaps Wounds (plural) might have been a more apt title for this startling debut novel by Racha Mounaged.